Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket, the only son of Gilbert Becket, a wealthy Norman merchant living in London, and his wife Matilda, was born on 21st December, 1120. Four daughters of the marriage also survived into adulthood. His father served a term as sheriff of the City, but later he suffered heavy losses when his properties were destroyed by fire. (1)

According to Frank Barlow "between 1130 and 1141, he was successively, but perhaps intermittently, a boarder at the Augustinian priory at Merton in Surrey, a pupil at one or more of the London grammar schools and a student at Paris." (2)

It is claimed by Edward Grim that in his youth he was more interested in rural sports than in his books and that his way of life was frivolous. He also came under the influence of an important Norman baron, Richer de l'Aigle, a great-grandson of a knight killed at the Battle of Hastings, and himself a soldier of considerable experience. He used to take Becket on holidays into the country, where they hunted and hawked. (3)

One of his biographers has pointed out: "His contemporaries described Thomas as a tall and spare figure with dark hair and a pale face that flushed in excitement. His memory was extraordinarily tenacious and, though neither a scholar nor a stylist, he excelled in argument and repartee. He made himself agreeable to all around him, and his biographers attest that he led a chaste life." (4)

Thomas Becket and Theobald of Bec

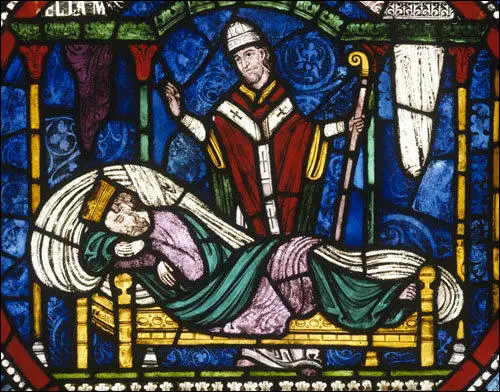

Thomas entered adult life as a city clerk and accountant in the service of the sheriffs. After three years he was introduced by his father to Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1141 he became a member of the household. His colleagues were a distinguished company that included the political philosopher John of Salisbury. Theobald was impressed with Becket and was sent to study civil and canon law at Bologna University. (5)

It is claimed that Becket was endowed with, or acquired, most of the qualities that make for worldly success. "His elegance was enhanced by vivacity.... He had excellent manners and was a good talker. Clearly he had the ability and the will to please: he was a charmer. John of Salisbury says that he had very acute senses of smell and hearing and a good memory. Such endowments make a little education go a very long way. He was undoubtedly intelligent, alert, responsive. Once he realized that he had to make his own way he became extremely ambitious." (6)

When Henry II became king in 1154, he asked Archbishop Theobald for advice on choosing his government ministers. On the suggestion of Theobald, Henry appointed Thomas Becket, who was twelve years his junior, as his chancellor. Becket's job was an important one as it involved the distribution of royal charters, writs and letters. People declared that "they had but one heart and one mind". The king and Becket soon became close friends. "Often the king and his minister behaved like two schoolboys at play." (7)

William FitzStephen tells the story of Becket and the king riding together through the streets of London. It was a cold day and when the king noticed an old man coming towards them, poor and clad in a thin and ragged coat. "Do you see that man? How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad! Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak." Becket agreed and the king replied: "You shall have the credit for this act of charity" and then attempted to strip his chancellor of his new "scarlet and grey" cloak. After a brief struggle Becket reluctantly allowed the king to overcome him. "The king then explained what had happened to his attendants and they all laughed loudly". (8)

Archbishop of Canterbury

When Theobald of Bec died in 1162, Henry chose Becket as his next Archbishop of Canterbury. The decision angered many leading churchmen. They pointed out that Becket had never been a priest, and had a reputation as a cruel military commander when he fought against the French king Louis VII. It was claimed that "who can count the number of persons he (Becket) did to death, the number whom he deprived of all their possessions... he destroyed cities and towns, put manors to the torch without thought of pity." (9)

Becket was also very materialistic (he loved expensive food, wine and clothes). His critics also feared that as Becket was a close friend of Henry II, he would not be an independent leader of the church. At first Becket refused the post: "I know your plans for the Church, you will assert claims which I, if I were archbishop, must needs oppose." Henry insisted and he was ordained priest on 2nd June, 1162, and consecrated bishop the next day. (10)

Herbert of Bosham claims that after being appointed as archbishop, Thomas Becket began to show a concern for the poor. Every morning thirteen poor people were brought to his home. After washing their feet Becket served them a meal. He also gave each one of them four silver pennies. John of Salisbury believed that Becket sent food and clothing to the homes of the sick, and that he doubled Theobald's expenditure on the poor. (11)

Instead of wearing expensive clothes, Becket now wore a simple monastic habit. As a penance (punishment for previous sins) he slept on a cold stone floor, wore a tight-fitting hairshirt that was infested with fleas and was scourged (whipped) daily by his monks. As a contemporary wrote: "Clad in a hair-shirt of the roughest kind which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he punished his flesh with the sparest diet, and his main drink was water... He often exposed his naked back to the lash." (12)

John Gillingham has argued that Becket had responded to the criticism his appointment had received: "In the eyes of respectable churchmen Becket... he did not deserve to be archbishop. He was too wordly and too much the King's friend. Wounded in his self-esteem Becket set out to prove, to an astonished world, that he was the best of all possible archbishops. Right from the start he went out of his way to oppose the King who, chiefly out of friendship, had made him an archbishop." (13)

Thomas Becket soon came into conflict with Roger of Clare, Earl of Hertford. Becket argued that some of the manors in Kent should come under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Roger disagreed and refused to give up this land. Becket sent a messenger to see Roger with a letter asking for a meeting. Roger responded by forcing the messenger to eat the letter.

In January, 1163, after a long spell in France, Henry II arrived back in England. Henry was told that, while he had been away, there had been a dramatic increase in serious crime. The king's officials claimed that over a hundred murderers had escaped their proper punishment because they had claimed their right to be tried in church courts. Those that had sought the privilege of a trial in a Church court were not exclusively clergymen. Any man who had been trained by the church could choose to be tried by a church court. Even clerks who had been taught to read and write by the Church but had not gone on to become priests had a right to a Church court trial. This was to an offender's advantage, as church courts could not impose punishments that involved violence such as execution or mutilation. There were several examples of clergy found guilty of murder or robbery who only received "spiritual" punishments, such as suspension from office or banishment from the altar. (14)

Thomas Becket in Exile

The king decided that clergymen found guilty of serious crimes should be handed over to his courts. At first, the Archbishop agreed with Henry on this issue and in January 1164, Henry published the Clarendon Constitution. After talking to other church leaders Becket changed his mind. Henry was furious when Becket began to assert that the church should retain control of punishing its own clergy. The king believed that Becket had betrayed him and was determined to obtain revenge. (15)

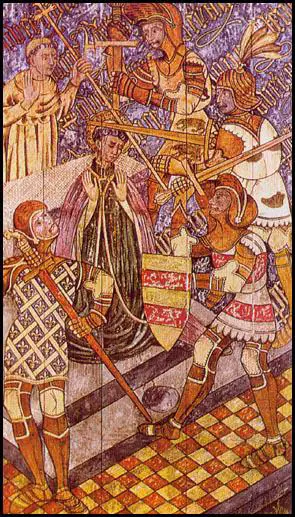

shows Becket denouncing the Clarendon Constitution (c.1210)

In 1164, the Archbishop of Canterbury was involved in a dispute over land. Henry ordered Becket to appear before his courts. When Becket refused, the king confiscated his property. Henry also claimed that Becket had stolen £300 from government funds when he had been Chancellor. Becket denied the charge but, so that the matter could be settled quickly, he offered to repay the money. Henry refused to accept Becket's offer and insisted that the Archbishop should stand trial. When Henry mentioned other charges, including treason, Becket decided to run away to France. (16)

Becket joined his former secretary, John of Salisbury in Rheims: The two men were very close friends: "John of Salisbury, a small and delicate man, warm, lively and playful, a joker with an eye to the ridiculous, the confident member of a learned elite, so sure of his scholarship that he could quote, to amuse his circle, classical authors and other embroideries of his own invention, was everything that Thomas Becket was not." (17)

However, the quarrel between Becket and the king put a strain upon their friendship: John would not abandon Becket's cause but he disagreed with the way Becket was dealing with the situation. (18) Becket now moved to Pontigny Abbey. According to Edward Grim, at least three times a day, his chaplain, was compelled by Becket, to "scourge him on the bare back until the blood flowed". Grim added that with these punishments he "killed all carnal desires". (19)

Under the protection of Henry's old enemy. King Louis VII, Becket organised a propaganda campaign against the monarchy. As Becket was supported by Pope Alexander III, Henry feared that he would be excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church). Alexander sent a letter to Henry urging him to make peace with Becket and suggesting that he restored him as Archbishop of Canterbury. (20)

John of Salisbury was also involved in negotiations with Henry II and Louis VII. The three men met at Angers in April 1166. In a letter to Becket he complained that he wasted money and lost two horses on the journey and that it obtained nothing of value. (21) Talks continued and on 7th January 1169, Becket and Henry met at Montmirail but they failed to reach an agreement. Alexander, finally ran out of patience and ordered Becket to agree a deal with Henry. (22) On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see. (23)

Death in the Cathedral

On his arrival, Becket excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church) Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the Archbishop of York, and other leading churchmen who had supported the king while he was away. Henry II, who was in Normandy at the time, was furious when he heard the news. Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence, claims he said: "A man who has eaten my bread, who came to my court poor and I have raised him high - now he draws up his heel to kick me in the teeth! He has shamed my kin, shamed my realm: the grief goes to my heart, and no one has avenged me!" (24)

Edward Grim points out that Henry added: "What miserable drones (the male of the honeybee that is stingless) and traitors have nourished and promoted in my realms, who let their lord to be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." (25) According to Gervase of Canterbury the king said: "How many cowardly, useless drones have I nourished that not even a single one is willing to avenge me of the wrongs I have suffered." (26) Four of Henry's knights, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, Reginald FitzUrse, and Richard Ie Breton, who heard Henry's angry outburst decided to travel to England to see Becket. (27)

When the knights arrived at Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170, they demanded that Becket pardon the men he had excommunicated. Edward Grim later reported: "The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop." (28)

Benedict of Peterborough, a prior based in Canterbury, wrote about what he knew about the murder: "While the body still lay on the pavement... some of them (people from Canterbury) brought bottles and carried off secretly as much blood as they could. Others cut off shreds of clothing and dipped them in the blood. Some of the blood left over was carefully collected and poured into a clean vessel... They stripped him of his outer garments... and in doing so they discovered that the body was covered in sackcloth, even from the thighs down to the knees." (29)

Saint Thomas Becket

Arnulf, the Bishop of Lisieux, was with Henry II when he heard the news of Becket's death. In a letter to Alexander III he wrote: "The king burst into loud cries and exchanged his royal robes for sackcloth... For three whole days he remained shut up in his chamber, and would neither take food nor admit anyone to comfort him." (30) William of Blois also wrote to the Pope about the murder. "I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero." (31)

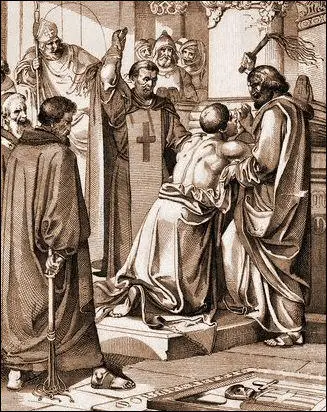

Pope Alexander III canonised Becket on 21st February, 1173 and he became a symbol of Christian resistance to the power of the monarchy. The king met Alexander III's legates at Avranches in May and submitted to their judgment. An agreement was signed on 21st May, 1172, that included the following: "That he (Henry) should at his own expense provide two hundred knights to serve for a year with the Templers in the Holy Land. That he himself should take the cross for a period of three years and depart for the Holy Land before the following Easter. That he should utterly abolish customs damaging to the Church which had been introduced in his reign." (32)

Henry admitted that, although he never desired the killing of Becket, his words may have prompted the murderers. On 12th July, 1174, Henry II did public penance, and was scourged at the archbishop's tomb. (33) The event was described by Gervase of Canterbury: "He (Henry II) set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury." (34)

In the Middle Ages the Church encouraged people to make pilgrimages to special holy places called shrines. It was believed that if you prayed at these shrines you might be forgiven for your sins and have more chance of going to heaven. Others went to shrines hoping to be cured from an illness they were suffering from. Becket's tomb at Canterbury Cathedral became the most popular shrine in England. When Becket was murdered local people managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness, epilepsy and leprosy. It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims. The monks also sold metal badges that had been stamped with the symbol of the shrine. The badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so that people would know they had visited the shrine. (35)

Primary Sources

(1) William FitzStephen, The Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1190)

Clad in a hair-shirt of the roughest kind which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he punished his flesh with the sparest diet, and his main drink was water... He often exposed his naked back to the lash.

(2) William FitzStephen, The Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1190)

One day they (King Henry II and Thomas Becket) were riding together through the streets of London. It was a hard winter and the king noticed an old man coming towards them, poor and clad in a thin and ragged coat. "Do you see that man? ... How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad!" said the king. '"Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak." "It would indeed... my king." Meanwhile the poor man drew near; the king stopped, and the chancellor with him. The king greeted him pleasantly and asked him if he would like a good cloak... The king said to the chancellor, "You shall have the credit for this act of charity," and laying hands on the chancellor's hood tried to pull off his cape, a new and very good one of scarlet and grey, which he was unwilling to part with... both of them had their hands fully occupied, and more than once seemed likely to fall off their horses. At last the chancellor reluctantly allowed the king to overcome him. The king then explained what had happened to his attendants. They all laughed loudly.

(3) Thomas Becket in a letter to Henry II (1166)

There are two principles by which the world is ruled: the authority of priests and the royal power. The authority of priests is the greater because God will demand an accounting of them even in regard to kings.

(4) Conversation between Henry II and Thomas Becket, quoted by Roger of Pontigny in his book Life of Thomas Becket. (c. 1176)

Henry II: Have I not raised you from the poor and humble to the summit of honour and rank?... How can it be that after so many favours... that you are not only ungrateful but oppose me in everything.

Thomas Becket: I am not unmindful of the favours which, not simply you, but God the giver of all things has decided to confer on me through you as St Peter says, '"We ought to obey God rather than men."

Henry II: I don't want a sermon from you: are you not the son of one of my villeins?

Thomas Becket: It is true that I am not of royal lineage; but then, neither was St Peter.

(5) Edward Grim, Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1180)

Who can count the number of persons he (Becket) did to death, the number whom he deprived of all their possessions. Surrounded by a strong force of knights, he attacked whole regions. He destroyed cities and towns, put manors and farms to the torch without a thought of pity.

(6) Thomas Becket in conversation with Herbert of Bosham, quoted in his book, Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1188)

Herbert, I want you to tell me what people are saying about me. And if you see anything in me that you regard as a fault, feel free to tell me in private. For from now on people will talk about me, but not to me. It is dangerous to men in power if no one dares to tell them when they go wrong.

(7) Edward Grim, Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1180)

The four knights with one attendant entered. They were received with respect as the servants of the King. The servants who waited on the Archbishop invited them to the table. They rejected the food, thirsting rather for blood. The Archbishop was informed that four men had arrived who wished to speak with him. He consented and they entered.

The knights sat for a long time in silence. After a while, however, the Archbishop turned to them, and carefully scanning the face of each one he greeted them in a friendly manner, but the wretches, who had made a treaty with death, answered his greetings with curses.

Fitz Urse, who seemed to be the chief and the most eager for crime among them, breathing fury, broke out in these words, "We have something to say to thee by the King's command.... The King commands that you depart with all your men from the kingdom... from this day there can be no peace with you, or any of yours, for you have broken the peace."

The Archbishop said, "I trust in the King of heaven, who suffered on the Cross: for from this day no one will see the sea between me and my church.... He who wants me will find me here." The knights sprang up and coming close to him they said, "We declare to you that you have spoken in peril of your head." "Do you come to kill me?" he answered. As they went out, he who was named Fitz Urse, called out, "In the King's name we order you, both clerk and monk, that you should take and hold that man."

The Archbishop returned to where he had sat before, and consoled his clerks, and told them not to fear; and, as it seemed to us who were present - it was him alone that they wanted to slay... We asked him to flee, but he did not forget his promise not to flee from his murderers from fear of death, and refused to go.

The knights came back with swords and axes and other weapons fit for the crime which their minds were set on... The knights cried out, "Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King?" Becket... in a clear voice answered, "I am here, no traitor to the King, but a priest... I am ready to suffer in His name... be it far from me to flee from your swords."

Having said this, he turned to the right under a pillar... and walked to the altar of St. Benedict the Confessor... The murderers followed him; "Absolve", they cried, "and restore to communion those whom you have excommunicatec and restore their powers to those whom you have suspended."

He answered, "I will not absolve them." "Then you shall die," they cried. "I am ready," he replied, "to die for my Lord... But in the name of Almighty God, I forbid you to hurt my people." They then laid hands on him, pulling and dragging him, that they might kill him outside the church. But when he could not be forced away from the pillar, one of them pulled on him. He said "Touch me not, Reginald; you owe me fealty; you and your accomplices act like madmen." The knight, fired with terrible rage, waved his sword over the Archbishop's head.

The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... by the same blow he wounded the arm of him that tell this story. For he, when the other monks and clerks fled, stuck close to the Archbishop...

Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... and saying in a low voice, "For the name of Jesus and the protection of the Church I am ready to embrace death." Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop.

The priest (Hugh of Horsea) who had entered with the knights... put his foot on the neck of the holy priest, and, horrible to say, scattered his brains and blood over the pavement, calling out to the others, "Let us away, knights; he will rise no more."

(8) Benedict of Peterborough describing what happened after the death of Thomas Becket (c. 1171)

While the body still lay on the pavement... some of them (people from Canterbury) brought bottles and carried off secretly as much blood as they could. Others cut off shreds of clothing and dipped them in the blood. Some of the blood left over was carefully collected and poured into a clean vessel... They stripped him of his outer garments... and in doing so they discovered that the body was covered in sackcloth, even from the thighs down to the knees.

(9) Arnulf, the Bishop of Lisieux, in a letter to the Pope Alexander III described Henry II's reaction to the news of Thomas Becket's death.

The king burst into loud cries and exchanged his royal robes for sackcloth... For three whole days he remained shut up in his chamber, and would neither take food nor admit anyone to comfort him.

(10) William of Blois wrote a letter to Pope Alexander III about the death of Thomas Becket (1171)

I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero.

Student Activities

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)