Pilgrimage

In the Middle Ages the Church encouraged people to make pilgrimages to special holy places called shrines. It was believed that if you prayed at these shrines you might be forgiven for your sins and have more chance of going to heaven. Others went to shrines hoping to be cured from an illness they were suffering from.

The most popular shrine in England was the tomb of Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. When Becket was murdered local people managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness/ epilepsy and leprosy. It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims.

Another important shrine was at Walsingham in Norfolk where there was a sealed glass jar that was said to contain the milk of the Virgin Mary. Erasmus visited Walsingham and described the shrine as being surrounded "on all sides with gems, gold and silver." He also added that the water from the Walsingham spring was "efficacious in curing pains of the head and stomach."

At other shrines people went to see the teeth, bones, shoes, combs etc. that were said to have once belonged to important Christian saints. The most common relics at these shrines were nails and pieces of wood that the keepers of the shrine claimed came from the cross used to crucify Jesus.

Important shrines in the Middle Ages included those at St. Winifred's Well, Lindisfarne, Glastonbury, Bromholm and St. Albans. When people arrived at the shrine they would pay money to be allowed to look at these holy relics. In some cases pilgrims were even allowed to touch and kiss them. The keeper of the shrine would also give the pilgrim a metal badge that had been stamped with the symbol of the shrine. These badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so that people would know they had visited the shrine.

Some people went on pilgrimages abroad. In Palestine, for example, it was possible to visit a cave that was supposed to contain the beds of Adam and Eve and a pillar of salt that had once been Lots wife.

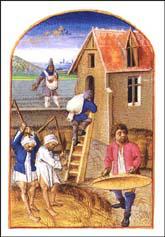

Travelling on long journeys in the Middle Ages was a dangerous activity. Pilgrims often went in groups to protect themselves against outlaws.

Wealthy people sometimes preferred to pay others to go on a pilgrimage for them. For instance, in 1352 a London merchant paid a man £20 to go on a pilgrimage to Mount Sinai.

In August 1535, Henry VIII sent a team of officials to find out what was going on in the monasteries. After reading their reports Henry decided to close down 376 monasteries. Monastery land was seized and sold off cheaply to nobles and merchants. They in turn sold some of the lands to smaller farmers. This process meant that a large number of people had good reason to support the monasteries being closed.

In 1538 Henry turned his attention to religious shrines in England. For hundreds of years pilgrims had visited shrines that contained important religious relics. Wealthy pilgrims often gave expensive jewels and ornaments to the monks that looked after these shrines. Henry decided that the shrines should be closed down and the wealth that they had created given to the crown.

The Pope and the Catholic church in Rome were horrified when they heard the news that Henry had destroyed St. Thomas Becket's Shrine. On 17 December 1538, the Pope announced to the Christian world that Henry VIII had been excommunicated from the Catholic church.

Primary Sources

(1) List of some of the relics held at St. Omer's Church in 1346.

A piece of Our Lord's Cross... Pieces of the Lord's tomb... A piece of the Lord's cradle... Some of the hairs of St. Mary. A piece of her robe... Part of St Thomas of Canterbury's tunic. Part of his chair. Shavings from the top of his head. Part of the blanket that covered him, and part of his woollen shirt... part of his hair shirt. Some of his blood.

(2) Benedict of Peterborough described what happened after the death of Thomas Becket. (c. 1175)

Some of the blood was carefully and cleanly collected and poured into a dean vessel and kept in the church.

(3) One of the worst diseases in the Middle Ages was 'sacred fire'. It was believed that a relic kept at a church in France could cure the disease. Hugh of Avallon, bishop of Lincoln, visited the church in about 1190.

We saw youths and maidens, old and young, cured of the 'sacred fire', some with their flesh eaten away, others with their bones completely destroyed, others still, having lost one or other of their limbs, living a normal life... you can see people of all ages of both sexes with their arms eaten away from wrist to elbow, or from elbow to shoulder, or with legs rotted from ankle to knees.

(4) Gervase of Canterbury, The Deeds of Kings (c.1210)

(Henry II) returned to England (1174)... he set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury.

(5) Matthew Paris, Greater Chronicle (c.1260)

A man came to St. Albans... He had a cross of wood that he said was made from the same cross on which Christ was crucified. But no one believed him. At last he came to a monastery called Brabham, in Norfolk. It was miserably poor... The monks were overjoyed to have such a treasure... miracles began in the monastery. The dead are raised to life, the blind have their sight, the lame walk, and those possessed of devils are freed.

(6) Part of a letter written by Margaret Paston to her husband in 1484.

When I heard you were ill I decided to go on pilgrimage to Walsingham... for you.

(7) One of the most unusual diseases in the Middle Ages was St Vitus dance. People who suffered from the disease found it difficult to keep their limbs still and so it looked like they were dancing. It was believed that if you attended St AImedha's church in Wales, you would be cured of the disease. In his book. Description of Wales, Gerald of Wales described a group of pilgrims visiting this church, (c. 1195)

The day was August 1st. Many people came here from distant parts... hoping to be healed... Men and women could be seen in the church and churchyard, singing and dancing. Suddenly they would fall down quite motionless, as if in a trance, and then as suddenly leap up again like lunatics... They accompanied these tasks with songs, but the notes were all out of tune... Later you could see the same people offering gifts at the altar, after which they appeared to rouse themselves from their trance and recover.

(8) Matthew Paris wrote about Bromholm Monastery in around 1250.

There he sent for the Prior and some of his brethren, and showed them the above-mentioned Cross, which was constructed of two pieces of wood, placed one across the other, and almost as wide as the hand of a man; he then humbly implored them to receive him into their order with the cross and the other relics which he had with him, as well as his two children.

(9) Erasmus visited the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham in 1513.

When you look in you would say it is the abode of saints, so brilliantly does it shine on all sides with gems, gold and silver… Our Lady stands in the dark at the right side of the altar… a little image, remarkable neither for its size, material or workmanship.

(10) D. J. Hall, English Medieval Pilgrimage (1965)

For centuries men lived with 'the firm belief that the end of the world was near and they also believed without question in the reality of Hell: from the pictures they saw and the descriptions given by the Church they were well acquainted with its inhabitants and the torments they practised. Their minds were therefore continually called upon to cope with situations in which their natural desires caused these beliefs to conflict. The expectancy of life being short, they were impelled to indulge their passions to the full; awareness of the awful fate which was the reward of sin drove them to almost any religious extravagance that might possibly bring redemption.

Violent antithesis is the essence of the middle ages. The contrast between rich and poor was vast, often as great as between men and beasts even though the conduct of both might be similar. For everyone life was precarious; hygiene was non-existent and horrible diseases were widespread; murder and robbery were everyday risks, the poor struggled desperately to survive and the rich were constantly on guard to protect their position or trying to destroy before being destroyed.

To the present century the middle ages appear romantic or horrifying or both, but it is impossible to gauge the happiness of people living at a time so totally different from the present. There are aspects of today which would numb a 12th-century man with horror and nausea, and our bigoted nationalism would seem to him as much out of order as his individual selfishness seems to us. The acceptance of signs and wonders, relics and miracles, by the most highly developed men of their age may seem to us incredible; but they might think it no less strange that the greater part of mankind today accepts, just as ignorantly, the manifestations of science.

(11) H. Amold-Forster, A History of England (1898)

Some of the monks lived good lives and did good work in teaching and helping the poor... there were others who lived bad lives, and spent their money upon themselves... When Henry made up his mind to destroy the monasteries and nunneries, it was not hard for him to find out many bad things which could truly be said of the monks and nuns, and which he could use as an excuse for taking away their property.