King Henry II

Henry, the eldest son of Matilda and Geoffrey Plantagent, Count of Anjou, was born in Le Mans on 5th March, 1133. (1) His father was an impressive military leader. John of Marmoutier claims: "As a soldier he attained the greatest glory, dedicating himself to the defence of the community and to the liberal arts.... This man was an energetic soldier and more shrewd in his upright dealings. He was meticulous in his justice and of strong character. He did not allow himself to be corrupted by excess or sloth, but spent his time riding about the country and performing illustrious feats. By such acts he endeared himself to all, and smote fear into the hearts of his enemies." (2)

The family lived in Angers. The chronicler, Ralph de Diceto, wrote in the 12th century: "The industry of the early Angevins caused this city to be sited in a commanding position. Its ancient walls are a glorious testament to its founders. The south-eastern quarter is dominated by a great house, which is indeed worthy to be called a palace." (3)

Anjou was largely a wine-producing area, lying in a fertile valley and enjoying a warm southern climate. "Its inhabitants were perceived by their neighbours, particularly the hostile Normans, as savages who desecrated churches, murdered priests and had disgusting table manners... The Angevin counts were renowned for their hot temper, voracious energy, military genius, political acumen, engaging charm and robust constitution." (4)

Matilda and Stephen

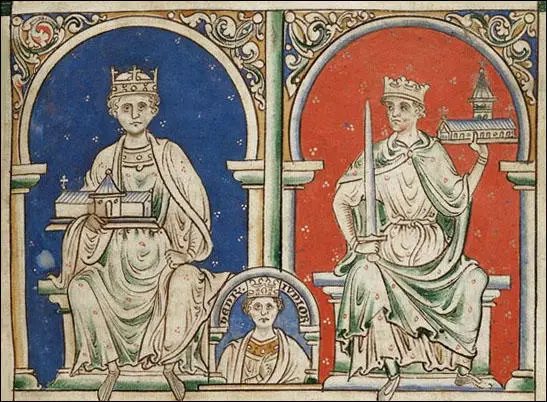

Matilda's father, Henry I, was the king of England. He only had two legitimate children (he had at least another twenty outside marriage). His only son William drowned in 1120. Henry's wife was dead so he married Adeliza of Louvain in the hope of obtaining another male heir. Adeliza, was 18 years-old and was considered to be very beautiful, but Henry was now in his fifties and no children were born. After four years of marriage he called all his leading barons to court and forced them to swear that they would accept his daughter, Matilda, as their ruler in the event of his dying without a male heir. This included Stephen of Blois, count of Mortain. Although he had a hereditary claim to the throne through his mother, Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror, he appears to have taken the oath willingly. (5)

The Normans had never had a woman leader. Norman law stated that all property and rights should be handed over to men. To the Normans this meant that her husband Geoffrey Plantagent would become their next ruler. The people of Anjou (Angevins) were considered to be barbarians by the Normans. Most Normans were unwilling to accept an Angevin ruler and when Henry died in December 1135, instead decided to help Matilda's cousin, Stephen, to become king. (6)

In 1138, Matilda's half-brother, Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, renounced his allegiance to Stephen. (7) Earl Robert attacked Stephen's forces in the west of England. He then travelled to Normandy and joined Geoffrey Plantagenet in an attempt to take control of the region. This was unsuccessful and Stephen was also able to capture Robert's castles in Kent. Robert returned to England and in November, 1139, his army managed to take control of Worcester from Stephen. (8)

King Stephen was eventually captured at the Battle of Lincoln (February, 1141). Stephen had promised the people of London more self-government. This helped him gain their support in the civil war. Matilda upset them by imposing a tax on the city's citizens. When Matilda went to be crowned the first queen of England, the people rebelled and she was forced to flee from the area. (9)

In September 1141, Robert, earl of Gloucester, was captured at the ford of Stockbridge by Flemish mercenaries under the command of William de Warenne, earl of Surrey. He was imprisoned first at Rochester, then moved back to Winchester, so as to assist the negotiations to exchange him for the king. Stephen was released on 1st November and Robert two days later. (10)

In Normandy, Henry's father, Geoffrey Plantagent, was making good progress in taking control of the region. Matilda's army was forced to retreat to Oxford where she was besieged. In December, 1141, she escaped and managed to walk the eight miles to Abingdon. Eventually, she established herself in Devizes and controlled the west of the country, whereas Stephen continued his rule from London. (11)

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagenets (2013), has pointed out: "Stephen and Matilda both saw themselves as the lawful successor of Henry I, and set up official governments accordingly: they had their own mints, courts, systems of patronage and diplomatic machinery. But there could not be two governments. Neither could be secure or guarantee that their writ would run, hence no subject could be fully confident in the rule of law. As in any state without a single, central source of undisputed authority, violent self-help and spoliation among the magnates exploded.... Forced labour was exacted to help arm the countryside. General violence escalated as individual landholders turned to private defence of their property. The air ran dark with the smoke from burning crops and the ordinary people suffered intolerable misery at the hands of marauding foreign soldiers." (12)

Stephen was accused of waging war on his own people. One anonymous chronicler wrote: "King Stephen set himself to lay waste that fair and delightful district, so full of good things, round Salisbury; they took and plundered everything they came upon, set fire to houses and churches, and, what was a more cruel and brutal sight, fired the crops that had been reaped and stacked all over the fields, consumed and brought to nothing everything edible they found. They raged with this bestial cruelty especially round Marlborough, they showed it very terribly round Devizes, and they had in mind to do the same to their adversaries all over England". (13)

Stephen's disputed succession resulted in considerable disorder. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938), has argued that the "worst tendencies of feudalism" emerged during this period and "private wars and private castles sprang up everywhere" and "hundreds of local tyrants massacred, tortured and plundered the unfortunate peasantry and choas reigned everywhere". Morton claims that this "taste of the evils of unrestrained feudal anarchy was sharp enough to make the masses welcome a renewed attempt of the crown to diminish the power of the nobles." (14)

In 1146 Count Geoffrey Plantagent of Anjou, had gained control of Normandy. He now suggested to King Louis VII of France that his son, Henry, aged thirteen, should marry his recently born child. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote to Louis explaining why he must reject the idea: "I have heard that the Count of Anjou is pressing to bind you under oath respecting the proposed marriage between his son and your daughter. This is something not merely inadvisable but also unlawful, because apart from other reasons, it is barred by the impediment of consanguinity. I have learned on trustworthy evidence that the mothers of the Queen and this boy are related in the third degree. Have nothing to do with the matter." (15)

Geoffrey Plantagent taught Henry about the conduct of business and war. "Twelfth-century French politics was violent, changeable and rough, and Geoffrey was an adept player." (16) In 1147 Henry arrived in England with a small band of mercenaries. His mother disapproved of this escapade and refused to help. So also did Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, who was in charge of Matilda's forces: "So with the impudence of youth he applied to the man against whom he was fighting and with characteristic generorosity Stephen sent him enough money to pay off his mercenaries and go home." (17)

In 1148 Queen Matilda decided to abandon her campaign to gain control of England. She returned to Normandy and lived in the priory of Notre-Dame-du-Pré. Over the next few years Matilda was able to combine active involvement in the business of the duchy with a semi-religious retreat. She also helped to finance the building of a new stone bridge over the Seine, linking Rouen with the royal park at Quevilly and the priory of Le Pré. (18)

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine was married to King Louis VII of France. She gave birth to two daughters, Marie (1145) and Alix (1150). Louis was bitterly diappointed and he still did not have a male heir. He was approaching thirty and began to fear that he would never father a son. His barons began to urge him to divorce Eleanor and find a younger wife who might give him a son. William of Newburgh claims that Eleanor was disatisfied with Louis complaining that she had "married a monk, not a king". (19)

Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis disagreed with the barons. He pointed out that if the royal couple's marriage was dissolved, Louis would lose Eleanor's inheritance, which would pass to whoever else she married, and the chances were that she might choose someone hostile to French interests. However, when Sugar died in January, 1151, the main obstacle to the divorce was removed. Bernard of Clairvaux was now the king's main adviser and he urged him to declare the marriage invalid. (20)

On 11th March 1152, Eleanor and Louis met at the royal castle of Beaugency to dissolve the marriage. Hugues de Toucy, Archbishop of Sens, presided, and Samson of Mauvoisin, Archbishop of Reims acted for Eleanor. Ten days later, Pope Eugene III granted an annulment on grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree. (Eleanor was Louis' third cousin once removed). Their two daughters were, however, declared legitimate. Custody of them was awarded to King Louis. Archbishop Samson received assurances from Louis that Eleanor's lands would be restored to her. (21)

Some historians have argued that it was Eleanor who was the motivating force behind the marriage annulment and that she already had decided who she wanted to marry, Henry of Anjou. After the death of his father, Geoffrey Plantagent in September 1151, Henry had inherited his father's empire. William of Newburgh states: "It is said that while she was still married to the King of France, she had aspired to marriage with the Norman duke, whose manner of life suited better with her own, and for that reason she desired and procured a divorce." (22)

King Louis VII considered Henry his main rival in Europe and would not have agreed to the divorce if he knew that she planned to merge their two empires. Eleanor took a barge along the Loire towards Tours before travelling to Poitiers. In April, 1152, Eleanor sent envoys to Henry asking him to come at once and marry her. (23)

Marion Meade, the author of Eleanor of Aquitaine (2002), has pointed out: "As Louis's former wife, she knew intimately the feelings of dislike for Henry; aside from flouting his authority as her overlord, she was about to deliver a stinging personal blow by marrying his chief enemy, a factor that may well have been part of her initial attraction to Henry. In a sense, she was about to take a deadly revenge, both personal and political, for fifteen years of boredom and entrapment." (24)

The ceremony took place in the eleventh-century cathedral of Saint-Pierre on 11th May, 1152. Henry was then nineteen years old, while Eleanor was nearly thirty. (25) Henry had "acquired by marriage almost half of what is now modern France. He was now master of a vast tract of land stretching from the English Channel to the Pyrenees, a domain that was ten times as large as the royal demesne of France. Through marrying Eleanor, he had founded an Angevin empire and established himself... as potentially the most powerful ruler in Europe." (26)

According to Henry of Huntingdon, the marriage of Henry and Eleanor "was the cause and promoter of great hatred and discord between the King of France and the Duke". (27) Louis VII decided to attack Henry's recently acquired territory in Normandy. Henry, reacted by marching west to Touraine and took a couple of the castles in the area. Louis decided to retreat to Paris and agreed to the Church's demands for a truce. (28)

King Henry II

In January 1153, Henry, now aged 20, surprised King Stephen by crossing the channel in midwinter. The two leaders made a series of truces which were turned into a permanent peace when the death of his son, Eustace, the Count of Boulogne, in August, persuaded the king to give up the struggle. In December, 1153, Stephen signed the Treaty of Winchester, that stated he was allowed to keep the kingdom on condition that he adopt Henry as his son and heir. (29)

Alison Weir has claimed that "Henry and Eleanor had a great deal in common: they were both strong, dynamic characters with forceful personalities and boundless energy. Both were intelligent, sharing cultural interests, and both had a strong sex-drive... Henry and Eleanor presided together over their court, travelled together on progress through their domains and slept together regularly." (30)

Eleanor gave birth to her first child, William, on 17th August 1153. Henry was overjoyed to have a male heir. After failing to produce a son in 15 years of marriage with King Louis VII, her achievement was seen as an act of God. Henry of Huntingdon wrote: "God granted a happy issue and peace shone forth. What boundless joy! What a happy day!" Henry went to London "where he was received with joy by enormous crowds and splendid processions". (31)

Stephen died in October 1154, and Henry became king. He took over without difficulty and it was the first undisputed succession to the throne since William the Conqueror took power in 1066. Henry II was the most powerful ruler in Western Europe with an empire which "stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees... but it is important to remember that although England provided him with great wealth as well as a royal title, the heart of the empire lay elsewhere, in Anjou, the land of his fathers." (32)

A second son, Henry, was born on 28th February 1155. However, the following year, the first child, William, died of a seizure. Other children soon followed, Matilda (6th January, 1156), Richard (8th September 1157), Geoffrey (23rd September 1158), Eleanor (13th October 1162), Joan (October 1165) and John (24th December 1166). Henry also had several extra-marital affairs and had several illegitimate children. (33)

From an early age Henry had been trained as the next king of England. Queen Matilda had employed the best scholars in Europe to educate her son. Henry was a willing student and never lost his love of learning. One of his close friends said that Henry had a tremendous memory and rarely forgot anything he was told. When he became king he arranged for the world's best scholars to visit his court so that he could discuss important issues with them. One of his officials, Peter of Blois, commented: "With King Henry II it is school every day, constant conversation with the best scholars and discussions of intellectual problems... He does not linger in his palaces like other kings but hunts through the country inquiring into what everyone was doing, especially judges whom he has made judges of others." (34)

Henry spent many hours studying Roman history. He was particularly interested in the way Emperor Augustus had successfully managed to gain control over the Roman Empire. Henry realised that, like Augustus, his first task must be to tackle those that had the power to remove him. This meant that Henry had to control England's powerful barons. His first step was to destroy all the castles that had been built during Stephen's reign. Henry also announced that, in future, castles could only be built with his permission. The new king also deported all the barons' foreign mercenaries. (35) William of Newburgh reported: "Henry gave signs... of a strict regard for justice... In the early days he gave serious attention to public order and exerted himself to revive the laws of England, which seemed under King Stephen to be dead and buried." (36)

When Henry II became king he asked Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for advice on choosing his government ministers. On the suggestion of Theobald, Henry appointed Thomas Becket, who was twelve years his junior, as his chancellor. Becket's job was an important one as it involved the distribution of royal charters, writs and letters. People declared that "they had but one heart and one mind". The king and Becket soon became close friends. "Often the king and his minister behaved like two schoolboys at play." (37)

William FitzStephen tells the story of Becket and the king riding together through the streets of London. It was a cold day and when the king noticed an old man coming towards them, poor and clad in a thin and ragged coat. "Do you see that man? How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad! Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak." Becket agreed and the king replied: "You shall have the credit for this act of charity" and then attempted to strip his chancellor of his new "scarlet and grey" cloak. After a brief struggle Becket reluctantly allowed the king to overcome him. "The king then explained what had happened to his attendants and they all laughed loudly". (38)

Henry then took action to unite the people of England. He allowed several of Stephen's officials to keep their government posts. Another strategy used by Henry was to arrange marriages between rival families. Henry was full of energy. When he was not working on government business he loved hunting. Even when he arrived back home it was said he rarely sat down. Henry, unlike most kings, cared little for appearances. He preferred hardwearing hunting clothes to royal robes. Henry also disliked the pomp and ceremony that went with being king. (39)

Contemporaries have left a vivid portrait of Henry II. According to Peter of Blois he was of medium height, with a strong square chest, and legs slightly bowed from endless days on horseback. His hair was reddish and his head was kept closely shaved. His blue-grey eyes were described as "dove-like" when in a good mood but "gleaming like fire when his temper was aroused", and flashing "like lightning" in bursts of passion. (40) Herbert of Bosham claimed that Henry had tremendous energy and was like a "human chariot dragging all after him". (41)

It has been suggested that Eleanor of Aquitaine was unhappy about her husband's relationship with Becket as it "relegated her to the side-lines of affairs and undermined her influence with the King". It has been pointed out that when Henry was abroad, "it was Becket, rather than Eleanor, who dispensed patronage on Henry's behalf and received important visitors to England". There is no evidence that unlike, Henry's mother, Matilda, Eleanor did not try to undermine Becket. (42)

Once Henry had complete control over England, he turned his attention to the rest of the British Isles. In 1157 Henry forced the king of Scotland, Malcolm IV, to surrender Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland to England. Henry also invaded Wales and Ireland. According to Gerald of Wales, the author of The History and Topography of Ireland (c. 1190): "No one can doubt how splendidly, how vigorously, how skillfully our most excellent king has practised armed warfare against his enemies in time of war... He not only brought strong peace in England... he won victories in remote and foreign lands". (43)

Henry believed people had to earn respect. He was often rude to members of the nobility. He was quick to lose his temper and often upset important people by shouting at them. Yet, when dealing with the poor or a defeated enemy. Henry had a reputation for being polite and kind. He also had a great sense of humour and even enjoyed a joke at his own expense.

Archbishop of Canterbury

When Theobald of Bec died in 1162, Henry chose Becket as his next Archbishop of Canterbury. The decision angered many leading churchmen. They pointed out that Becket had never been a priest, and had a reputation as a cruel military commander when he fought against the French king Louis VII. It was claimed that "who can count the number of persons he (Becket) did to death, the number whom he deprived of all their possessions... he destroyed cities and towns, put manors to the torch without thought of pity." (44)

Becket was also very materialistic (he loved expensive food, wine and clothes). His critics also feared that as Becket was a close friend of Henry II, he would not be an independent leader of the church. At first Becket refused the post: "I know your plans for the Church, you will assert claims which I, if I were archbishop, must needs oppose." Henry insisted and he was ordained priest on 2nd June, 1162, and consecrated bishop the next day. (45)

Herbert of Bosham claims that after being appointed as archbishop, Thomas Becket began to show a concern for the poor. Every morning thirteen poor people were brought to his home. After washing their feet Becket served them a meal. He also gave each one of them four silver pennies. John of Salisbury believed that Becket sent food and clothing to the homes of the sick, and that he doubled Theobald's expenditure on the poor. (46)

Instead of wearing expensive clothes, Becket now wore a simple monastic habit. As a penance (punishment for previous sins) he slept on a cold stone floor, wore a tight-fitting hairshirt that was infested with fleas and was scourged (whipped) daily by his monks. As a contemporary wrote: "Clad in a hair-shirt of the roughest kind which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he punished his flesh with the sparest diet, and his main drink was water... He often exposed his naked back to the lash." (47)

John Gillingham has argued that Becket had responded to the criticism his appointment had received: "In the eyes of respectable churchmen Becket... he did not deserve to be archbishop. He was too wordly and too much the King's friend. Wounded in his self-esteem Becket set out to prove, to an astonished world, that he was the best of all possible archbishops. Right from the start he went out of his way to oppose the King who, chiefly out of friendship, had made him an archbishop." (48)

Thomas Becket soon came into conflict with Roger of Clare, Earl of Hertford. Becket argued that some of the manors in Kent should come under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Roger disagreed and refused to give up this land. Becket sent a messenger to see Roger with a letter asking for a meeting. Roger responded by forcing the messenger to eat the letter.

In January, 1163, after a long spell in France, Henry II arrived back in England. Henry was told that, while he had been away, there had been a dramatic increase in serious crime. The king's officials claimed that over a hundred murderers had escaped their proper punishment because they had claimed their right to be tried in church courts. Those that had sought the privilege of a trial in a Church court were not exclusively clergymen. Any man who had been trained by the church could choose to be tried by a church court. Even clerks who had been taught to read and write by the Church but had not gone on to become priests had a right to a Church court trial. This was to an offender's advantage, as church courts could not impose punishments that involved violence such as execution or mutilation. There were several examples of clergy found guilty of murder or robbery who only received "spiritual" punishments, such as suspension from office or banishment from the altar. (49)

Thomas Becket in Exile

The king decided that clergymen found guilty of serious crimes should be handed over to his courts. At first, the Archbishop agreed with Henry on this issue and in January 1164, Henry published the Clarendon Constitution. After talking to other church leaders Thomas Becket changed his mind. Henry was furious when Becket began to assert that the church should retain control of punishing its own clergy. The king believed that Becket had betrayed him and was determined to obtain revenge. (50)

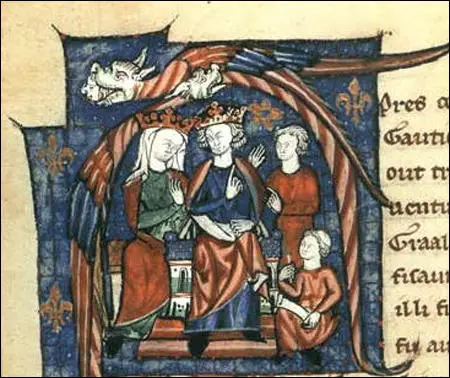

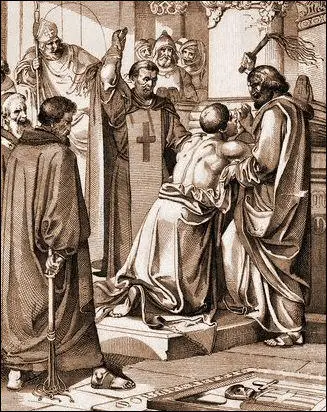

shows Becket denouncing the Clarendon Constitution (c.1210)

In 1164, the Archbishop of Canterbury was involved in a dispute over land. Henry ordered Becket to appear before his courts. When Becket refused, the king confiscated his property. Henry also claimed that Becket had stolen £300 from government funds when he had been Chancellor. Becket denied the charge but, so that the matter could be settled quickly, he offered to repay the money. Henry refused to accept Becket's offer and insisted that the Archbishop should stand trial. When Henry mentioned other charges, including treason, Becket decided to run away to France. (51)

Becket joined his former secretary, John of Salisbury in Rheims: The two men were very close friends: "John of Salisbury, a small and delicate man, warm, lively and playful, a joker with an eye to the ridiculous, the confident member of a learned elite, so sure of his scholarship that he could quote, to amuse his circle, classical authors and other embroideries of his own invention, was everything that Thomas Becket was not." (52)

However, the quarrel between Becket and the king put a strain upon their friendship: John would not abandon Becket's cause but he disagreed with the way Becket was dealing with the situation. (53) Becket now moved to Pontigny Abbey. According to Edward Grim, at least three times a day, his chaplain, was compelled by Becket, to "scourge him on the bare back until the blood flowed". Grim added that with these punishments he "killed all carnal desires". (54)

Under the protection of Henry's old enemy. King Louis VII, Becket organised a propaganda campaign against the monarchy. As Becket was supported by Pope Alexander III, Henry feared that he would be excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church). Alexander sent a letter to Henry urging him to make peace with Becket and suggesting that he restored him as Archbishop of Canterbury. (55)

John of Salisbury was also involved in negotiations with Henry II and Louis VII. The three men met at Angers in April 1166. In a letter to Becket he complained that he wasted money and lost two horses on the journey and that it obtained nothing of value. (56) Talks continued and on 7th January 1169, Becket and Henry met at Montmirail but they failed to reach an agreement. Alexander, finally ran out of patience and ordered Becket to agree a deal with Henry. (57) On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see. (58)

Death in the Cathedral

On his arrival, Becket excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church) Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the Archbishop of York, and other leading churchmen who had supported the king while he was away. Henry II, who was in Normandy at the time, was furious when he heard the news. Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence, claims he said: "A man who has eaten my bread, who came to my court poor and I have raised him high - now he draws up his heel to kick me in the teeth! He has shamed my kin, shamed my realm: the grief goes to my heart, and no one has avenged me!" (59)

Edward Grim points out that Henry added: "What miserable drones (the male of the honeybee that is stingless) and traitors have nourished and promoted in my realms, who let their lord to be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." (60) According to Gervase of Canterbury the king said: "How many cowardly, useless drones have I nourished that not even a single one is willing to avenge me of the wrongs I have suffered." (61) Four of Henry's knights, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, Reginald FitzUrse, and Richard Ie Breton, who heard Henry's angry outburst decided to travel to England to see Becket. (62)

When the knights arrived at Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170, they demanded that Becket pardon the men he had excommunicated. Edward Grim later reported: "The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop." (63)

Benedict of Peterborough, a prior based in Canterbury, wrote about what he knew about the murder: "While the body still lay on the pavement... some of them (people from Canterbury) brought bottles and carried off secretly as much blood as they could. Others cut off shreds of clothing and dipped them in the blood. Some of the blood left over was carefully collected and poured into a clean vessel... They stripped him of his outer garments... and in doing so they discovered that the body was covered in sackcloth, even from the thighs down to the knees." (64)

Saint Thomas Becket

Arnulf, the Bishop of Lisieux, was with Henry II when he heard the news of Becket's death. In a letter to Alexander III he wrote: "The king burst into loud cries and exchanged his royal robes for sackcloth... For three whole days he remained shut up in his chamber, and would neither take food nor admit anyone to comfort him." (65) William of Blois also wrote to the Pope about the murder. "I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero." (66)

Pope Alexander III canonised Becket on 21st February, 1173 and he became a symbol of Christian resistance to the power of the monarchy. The king met Alexander III's legates at Avranches in May and submitted to their judgment. An agreement was signed on 21st May, 1172, that included the following: "That he (Henry) should at his own expense provide two hundred knights to serve for a year with the Templers in the Holy Land. That he himself should take the cross for a period of three years and depart for the Holy Land before the following Easter. That he should utterly abolish customs damaging to the Church which had been introduced in his reign." (67)

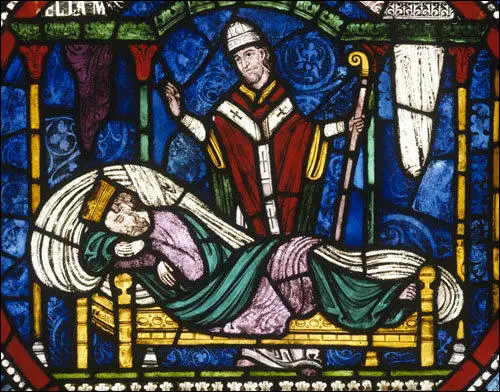

Henry admitted that, although he never desired the killing of Becket, his words may have prompted the murderers. On 12th July, 1174, Henry II did public penance, and was scourged at the archbishop's tomb. (68) The event was described by Gervase of Canterbury: "He (Henry II) set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury." (69) Ralph de Diceto added: "He spent the rest of the day and also the whole of the following night in bitterness of soul, given over to prayer and sleeplessness, and continuing his fast for three days... There is no doubt that he had by now placated the martyr." (69a)

In the Middle Ages the Church encouraged people to make pilgrimages to special holy places called shrines. It was believed that if you prayed at these shrines you might be forgiven for your sins and have more chance of going to heaven. Others went to shrines hoping to be cured from an illness they were suffering from. Becket's tomb at Canterbury Cathedral became the most popular shrine in England. When Becket was murdered local people managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness, epilepsy and leprosy. It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims. The monks also sold metal badges that had been stamped with the symbol of the shrine. The badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so that people would know they had visited the shrine. (70)

In his discussions with Pope Alexander III, Henry agreed to allow the church courts to continue to deal with all criminal charges against clerics. The practice of "benefit of clergy" went on until the Protestant Reformation. However, as A. L. Morton pointed out: "Yet the victory of the church was not complete. The state had to surrender criminal cases: civil cases it retained. And during this period there grew up what came to be called the common law, a body of law holding good throughout the land and overriding all local laws and customs." (71)

Eleanor and Henry

Gerald of Wales argues that King Henry II was not a good husband and "in domestic matters he was hard to deal with" and that he was an "open adulterer" throughout the marriage. (72) William of Newburgh is less critical of Henry and suggests that he did not commit adultery until Eleanor of Aquitaine was past childbearing age. (73) Eleanor was 44 years old by the time she gave birth to John in 1166 and it is assumed that this marked the end of their sexual relationship. (74)

Eleanor now moved to Aquitaine to manage her unruly vassals: "Eleanor may well have welcomed the chance of autonomy, not to mention a more gracious mode of living than that experienced by Henry's entourage, whose accommodation more often resembled a campsite than a court, but their marriage had always been based on business, and it was business that provided the primary reason for Eleanor's removal from England." (75)

In 1167 Henry began a relationship with Rohese de Clare, Countess of Lincoln, and the sister of Roger de Clare, Earl of Hertford, who was said to be the most beautiful woman in England. Another mistress was Avice de Stafford. His main love was Rosamund de Clifford, the daughter of a a minor Norman knight, Walter de Clifford, who owned land in Herefordshire. Although during this period he was usually out of the country, he spent time with her in Woodstock whenever he could. (76)

Gerald of Wales called her "Rose of Unchastity" and claims Henry openly paraded her at his court as his mistress. (77) There are several stories about how Eleanor arranged for Rosamund to be murdered. (78) This included Eleanor going to meet Rosamund and offering her a choice between a dagger and a cup of poisoned wine. Another version is that Eleanor arranged for her to be bled to death. In reality Eleanor almost certainly never met her. (79)

During this period Eleanor was based at Poitiers, where she refurbished the Maubergeonne Tower. She was also a generous benefactor to Fontevraud Abbey. Eleanor appointed her own officials and in 1170 she arranged for her 13-year-old son, Richard, to be granted the title of Duke of Aquitaine. Eleanor, dealt with the problems of imposing taxes on individuals and commodities such as wheat, salt and wine. Over the next few years Richard "got his first taste of the exercise of authority in his mother's company, and in her ancestral territories". (80)

Henry the Young

In 1158, the four-year-old, Henry the Young was betrothed to the two-year-old Margaret, the six-month-old daughter of Louis VII of France, Eleanor's former husband, and Constance of Castile, his second wife. The marriage was ratified in October 1160 and rushed through the following month by Henry II, who wished to acquire control over the Norman Vexin, her dowry. Under the terms of the agreement, Margaret was to be brought up by Eleanor. (81)

Negotiations continued over the next few years and in 1169 it was decided at a meeting at Montmirail that Henry the Young would inherit Normandy, Anjou and England after his marriage to the 12-year-old Margaret. It was also agreed that Henry's son, Richard, would marry Alais, another daughter of Louis VII. (82)

In June 1170, the fifteen-year-old Henry was crowned king although his father was still alive. However, he did not have any power and it was just an attempt by the king to show his commitment to merging of the two kingdoms. Thomas Becket was in exile and so he was crowned by Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the Archbishop of York. This ceremony took place without permission of the pope, Alexander III. (83)

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagenets (2013) has pointed out: "Henry has been portrayed by the chroniclers as a feckless and fatuous youth. In person, he was tall, blond and good-looking, with highly cultivated manners. He was a skilled horseman, with a real fondness for the tournament and a huge household of followers who egged on his chivalrous ambitions." (84) The government official, Walter Map, described Henry as "lovable, eloquent, handsome, gallant, every way attractive, a little lower than the angels". (85)

On 27th August 1172, Eleanor's eldest son, Henry the Young, aged seventeen, married Margaret of France, daughter of her former husband, King Louis VII, and his second wife, Constance of Castile, at Winchester Cathedral. It would hoped that if Margaret gave birth to a son, who would have a claim to both family empires. However, they remained childless. (86)

Henry developed an expensive life-style without the means to pay for it and was heavily in debt. His father had promised him that he would one succeed him as king of England, and inherit land in Normandy and Anjou. He also endowed him with titles, but "as he approached manhood his access to landed revenue and power - the essence of kingship - was strictly limited". (87)

Eleanor's Revolt

Eleanor suggested that Henry the Younger should be given England, Anjou or Normandy to rule. Henry refused and Eleanor began to develop plans to overthrow of her husband. On 5th March 1173, Henry left Chinon Castle and rode for Paris and went to stay with King Louis VII. Soon afterwards, Louis announced that he acknowledged that Henry was the new king of England. Henry II was furious and declared war on France. He was greatly dismayed when he heard that Eleanor and two more of his sons, Richard the Lionheart and Geoffrey of Brittany, had joined the rebellion. (88) Ralph de Diceto recorded that Henry's sons "took up arms against their father at just the time when everywhere Christians were laying down their arms in reverence for Easter." (89)

William of Newburgh reported that "the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French King, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him". (90) Andrea Hopkins has argued that Eleanor identified more with the interests of her sons rather than those of her husband. (91)

One historian has pointed out that the brothers "were typical sprigs of the Angevin stock... they wanted power as well as titles". (92) Gerald of Wales quotes one of his sons, Geoffrey of Brittany, as saying: "It is our proper nature, planted in us by inheritance from our ancestors, that none of us should love the other, but that always, brother against brother and son against father, we try our utmost to injure one another?" (93)

Eleanor has been accused of being the ring-leader of the revolt against Henry: "It is clear that her sympathies lay wholeheartedly with her sons and that, like a lioness fighting to protect her cubs, she was prepared to resort to drastic measures to ensure that they received their just deserts... Henry and his brothers wanted autonomous power in the hands assigned to them, even if it meant the overthrow of their father; Eleanor wanted justice for her sons and, consequently, more power and influence for herself. This, she must have known, could only be achieved through the removal of her husband from the political scene." (94)

In a letter sent to Eleanor by Rotrou, Archbishop of Rouen, under the instructions of Henry II, he made it clear that he considered that his wife was behind the revolt as she had "made the fruits of your union with our Lord King rise up against their father". He added: "before events carry us to a dreadful conclusion, return with your sons to the husband whom you must obey and with whom it is your duty to live... Bid your sons, we beg you, to be obedient and devoted to their father." (95)

Eleanor's powerful lords from Aquitaine joined the rebellion. Henry the Younger also did a deal with William the Lion, the King of Scotland, who promised him Northumbria if he helped defeat his father. However, before the fighting began, Eleanor was captured by the agents of Henry. According to Gervase of Canterbury, Eleanor, left Poiters for Chartres, on a horse, dressed as a man. She was recognized and arrested and taken to Henry who was based in Rouen. (96)

Ranulf de Glanville, the sheriff of Lancashire, was loyal to Henry II, succeeded in capturing an English ally of the Scottish king, Hamo de Massy, This was followed by the defeat of William the Lion, king of Scots, in July 1174. William was captured and taken to Normandy. He was rewarded by being appointed Justice of the King's Court. (97)

In July 1173 Henry defeated his sons at Verneuil Castle. His soldiers also had success against the Scots in Northumbria. His loyal commander, Richard de Lucy, defeated hired bands of Flemish mercenaries at Fornham, near Bury St Edmunds. (98) By the end of September 1174 it was all over. After their surrender, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey all had their allowances increased. Henry was formally assigned two castles in Normandy, to be chosen by his father, and 15,000 Angevin pounds for his upkeep. (99) However, all three sons had to promise never to "demand anything further from the Lord King, their father, beyond the agreed settlement... and withdrew neither themselves nor their service from him." (100)

However, he was unwilling to forgive Eleanor and she spent the next fourteen years in captivity. The records suggest that she was permitted two chamberlains and a maid named Amaria. Lisa Hilton, the author of Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens (2008) claims that although "Eleanor's living conditions were reasonable, they were not commensurate with her status, as her clothes were no finer than a servant girl's and apparently she and Amaria had to share the same bed." (101)

Ranulf de Glanville, used his position to help his nephew Hubert Walter. He became Glanville's chief deputy in England. He came to the notice of Henry II and this "tall, elegant and handsome" became the king's chaplain. (102) Walter carried money to south Wales for the king's troops, and conveyed messages to King Philip II of France. He was also asked to mediate in the dispute between Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury and the monks of Christ Church over his proposal to establish a house of canons at Lambeth. (103)

Death of Henry the Young

On 19th June, 1177, Henry the Young's wife, Margaret, finally gave birth to her first child, William. The joy at the birth of a direct heir to the Angevin empire was short-lived, for the infant died three days later. Matthew Strickland, the author of Henry the Young King (2016) has pointed out: "Whereas his father's extra-marital affairs were as numerous as they were notorious, young Henry is not known to have had any mistresses, or to fathered any illegitimate children... this was unusual among men of his rank and power." (104)

In 1182 Henry the Young renewed his demands for more power, and once again fled to the French court in defiance of his father. Henry II responded by increasing his allowance by an extra 110 Angevin pounds a day for himself and his wife. However, this did not stop him supporting the rebellious barons of Aquitaine against his brother, Richard the Lionheart, who was trying to bring this area under control. The king sent his soldiers to help Richard against his rebellious son. "Returning from a raid on Angoulême, however, he was refused entry to Limoges by its exasperated citizens, and set off on a haphazard expedition around southern Aquitaine, despoiling the monastery of Grandmont and the shrines of Rocamadour." (105) Peter of Blois accused Henry the Young of being "a leader of freebooters who consorted with outlaws and excommunicates". (106)

Henry the Young fell seriously ill with dysentery. A message was sent to Henry II informing him that his son was dying. The king's advisors suspected a trap and warmed against him visiting his son. He therefore sent his physician, some money and as a token of his forgiveness, a sapphire ring that had belonged to Henry I. He also said that he hoped that after his son recovered, they would be reconciled. When he received the ring he replied asking his father to show mercy to his mother, Queen Eleanor. (107)

Henry the Young realised he was dying and "overcome with remorse for his sins, asked to be garbed in a hair shirt and a crusader's cloak and laid on a bed of ashes on the floor, with a noose round his neck and bare stones at his head and feet, as befitted a penitent." Henry died on 11th June, 1183. (108) The following year Henry II held a meeting in London with Richard and they agreed to bring an end to their conflict. Despite threats that he would be disinherited, Richard continued to have a difficult relationship with his father. (109)

In the autumn of 1183, Henry II told Richard the Lionheart that he should give up Aquitaine to his youngest brother, John, who had always remained loyal to his father. In return, he would become heir to England, Normandy and Anjou. Richard refused as he believed as the eldest son left alive, he should inherit all his father's empire when he died. He also rejected the suggestion that another brother, Geoffrey, should be given Brittany to rule. (110) Henry now came up with another plan. He told Richard he would release his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, from prison, if he agreed to surrender his rights to Aquitaine. Richard, who was devoted to his mother, agreed to this suggestion. (111)

Geoffrey of Brittany, died aged twenty-seven on 19th August, 1186. Roger of Howden said he succumbed to fever. (112) However, Ralph de Diceto, claims he took part in a tournament and fell off his horse and was trampled to death. (113) A son and heir, Arthur of Brittany, was born six months after his death. (114)

Richard the Lionheart

In January 1189, Henry became ill. From his sickbed he sent messages begging Richard the Lionheart to return to his side. However, he continued to fight alongside Philip II and he considered nominating his youngest son, John, as his heir. On 12th June Richard attacked Henry at his base in Le Mans. Henry was forced to flee and was taken to Chinon Castle. (115)

By the end of the month Maine was overrun and Tours had fallen. On 3rd July, Henry left his sickbed to meet Philip II at Ballan-Miré. He accepted his long list of demands including the confirmation of Richard as his heir in all lands on both sides of the Channel. Henry was so ill that the fifty-six year old king had to be held upright on his horse by his attendants. After signing the treaty he was too sick to ride and was carried home in a litter. On his return, Henry asked for a list to be drawn up of his former supporters who had joined Richard's rebellion. According to Gerald of Wales, the name at the top of the list was his favourite son John. (116)

Henry II died on 6th July 1189. Henry's son, Richard, now became king of England. One of his first acts as king was to send William Marshal to England with orders to release his mother from prison. Richard also restored to her control the lands and revenues that she had enjoyed before the revolt of 1173. (117) Eleanor responded by toured England encouraging the barons to support her son and announced a general amnesty of prisoners. (118) Roger of Howden claims she went from "city to city and castle to castle", holding "queenly courts", releasing prisoners and exacting oaths from all freemen to "be loyal to her son as their as yet uncrowned king". (119)

Primary Sources

(1) William of Newburgh, History of English Affairs (c. 1200)

After the miseries they had endured the people hoped for better things from the new monarch, especially as Henry gave signs... of a strict regard for justice... In the early days he gave serious attention to public order and exerted himself to revive the laws of England, which seemed under King Stephen to be dead and buried.

(2) Gerald of Wales, The History and Topography of Ireland (c. 1190)

No one can doubt how splendidly, how vigorously, how skillfully our most excellent king has practised armed warfare against his enemies in time of war... He not only brought strong peace in England... he won victories in remote and foreign lands.

(3) Peter of Blois, The Chronicles of Peter of Blois (c. 1185)

With King Henry II it is school every day, constant conversation with the best scholars and discussions of intellectual problems... He does not linger in his palaces like other kings but hunts through the country inquiring into what everyone was doing, especially judges whom he has made judges of others.

(4) Ralph de Diceto, Pictures of History (c. 1180)

Henry sought to help those of his subjects who could least help themselves. When the king found that the sheriffs were using the public power in their own interests... he entrusted rights of justice to other loyal men of his realm.

(5) Writ issued by Henry II to those electing the Bishop of Winchester (1171)

I order you to hold a free election, but forbid you to elect anyone but Richard my clerk.

(6) Gerald of Wales, The History and Topography of Ireland (c. 1190)

Henry dreaded war... and grieved more than any prince for those lost in battle, mourning them with a grief far greater than the love he gave to the living. He could scarcely spare an hour to hear mass... The revenues of the churches he drew into his own treasury... as he was always engaged in mighty wars, he spent all the money he could get, and lavished upon soldiers what was due to the priests.

(7) Peter of Blois, Henry's secretary, in a letter to his friend Henry FitzEmpress (c. 1185)

If the king said he will remain in a place for a day.... he is sure to upset all the arrangements by departing early in the morning. And you then see men dashing around as if they were mad... If, on the other hand, the king orders an early start, he is sure to change his mind, and you can take it for granted that he will sleep until midday. Then you will see the packhorses loaded and waiting, the carts prepared, the courtiers dozing, traders fretting, and everyone grumbling... Many a time when the king was sleeping, a message would be passed from his chamber about a city or town he intended to go to... But when our courtiers had gone ahead almost the whole day's ride, the king would turn aside to some other place... I hardly dare say it, but I believe that in truth he took a delight in seeing what a fix he put us in.

(8) Herbert of Bosham, Life of Thomas Becket (c. 1188)

The king (Henry II) demanded that the clergy seized or convicted of great crimes should be deprived of the protection of the Church and handed over to his officers, adding that they would be less likely to do evil if... they were subjected to physical punishment.

(9) Bishop Gilbert Foliot to Thomas Becket at their meeting at Clarendon (1164)

These hands, these arms, even these bodies are not ours; they are our lord king's, and they are ready at his will whatever it may be.

(10) Thomas Becket in a letter to Henry II (1166)

There are two principles by which the world is ruled: the authority of priests and the royal power. The authority of priests is the greater because God will demand an accounting of them even in regard to kings.

(11) Conservation between Henry II and Thomas Becket, quoted by Roger of Pontigny in his book Life of Thomas Becket. (c. 1176)

Henry II: Have I not raised you from the poor and humble to the summit of honour and rank?... How can it be that after so many favours... that you are not only ungrateful but oppose me in everything.

Thomas Becket: I am not unmindful of the favours which, not simply you, but God the giver of all things has decided to confer on me through you as St Peter says, '"We ought to obey God rather than men."

Henry II: I don't want a sermon from you: are you not the son of one of my villeins?

Thomas Becket: It is true that I am not of royal lineage; but then, neither was St Peter.

(12) Clarendon Constitution (January, 1164)

1. If a controversy arise between laymen, or between laymen and clerks, or between clerks concerning patronage and presentation of churches, it shall be treated or concluded in the court of the lord king.

2. Churches of the lord king's fee cannot be permanently bestowed without his consent and grant.

3. Clerks charged and accused of any matter, summoned by the king's justice, shall come into his court to answer there to whatever it shall seem to the king's court should be answered there; and in the church court to what it seems should be answered there; however the king's justice shall send into the court of holy Church for the purpose of seeing how the matter shall be treated there. And if the clerk be convicted or confess, the church ought not to protect him further.

4. It is not permitted the archbishops, bishops, and priests of the kingdom to leave the kingdom without the lord king's permission. And if they do leave they are to give security, if the lord king please, that they will seek no evil or damage to king or kingdom in going, in making their stay, or in returning.

(13) Andreas Trevisano, Italian ambassador to England between 1497 and 1502.

If the criminal (in England) can read, he asks to defend himself by the book... if he can read it he is liberated from the power of the law, and given as a clerk into the hands of the bishop.

(14) John Gillingham, The Lives of the Kings and Queens of England (1975)

Only in the last weeks of his life had the task of ruling his immense territories been too much for Henry. A man of boundless energy he rode ceaselessly from one corner of his empire to another. He travelled so fast that he gave the impression of being everywhere at once - an impression which helped to keep men loyal. He never seemed to be still; when he was not working, he was out hunting. He cared little for appearances; he dressed simply and enjoyed plain food. Although the central government offices, the Chancery, the Chamber and the Constabulary travelled around with him, the sheer size of the empire inevitably stimulated the growth of localised administrations which could deal with routine matters of justice and finance in his absence. In England, where there was a strong administrative tradition going back to Anglo Saxon days, government became increasingly complex and bureaucratic.

This development, taken together with Henry's interest in rational reform, has led to him being regarded as the founder of the English common law, and as a great and creative king. There is much to be said for this view of Henry, but in his own eyes these matters were of secondary importance - whatever their consequences in the long run may have been. To him what really mattered was family politics and he died believing that he had failed. But for over thirty years he had succeeded.

Student Activities

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Richard the Lionheart (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Taxation in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

King John and the Magna Carta (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

Wandering Minstrels in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

The Peasants' Revolt (Answer Commentary)

Death of Wat Tyler (Answer Commentary)

Medieval Historians and John Ball (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)