King John

John, the youngest son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, was born in Oxford on 24th December 1166. He was the younger brother of Eleanor's first children, William IX of Poitiers (17th August 1153), Henry the Young (28th February 1155), Matilda (6th January, 1156), Richard the Lionheart (8th September 1157), Geoffrey of Brittany (23rd September 1158), Eleanor (13th October 1162) and Joan (October 1165). (1)

Eleanor was 44 years old by the time she gave birth to John and it is assumed that this marked the end of their sexual relationship. (2) Eleanor now moved to Aquitaine to manage her unruly vassals: "Eleanor may well have welcomed the chance of autonomy, not to mention a more gracious mode of living than that experienced by Henry's entourage, whose accommodation more often resembled a campsite than a court, but their marriage had always been based on business, and it was business that provided the primary reason for Eleanor's removal from England." (3)

Virtually nothing is known of John's childhood and early education. He was initially brought up in the household of Henry the Young, so that he could learn to be a knight. (4) This was followed by time in the home of the king's justiciar, Ranulf de Glanville, where he was taught about the business of government. (5)

Eleanor strongly believed that her husband should give their sons land to manage. She suggested that her eldest son should be given England, Anjou or Normandy to rule. Henry refused and Eleanor began to develop plans to overthrow of her husband. On 5th March 1173, Henry left Chinon Castle and rode for Paris and went to stay with Louis VII. Soon afterwards, Louis announced that he acknowledged that Henry was the new king of England. Henry II was furious and declared war on France. He was greatly dismayed when he heard that Eleanor and two more of his sons, Richard the Lionheart and Geoffrey of Brittany, had joined the rebellion. (6) Ralph de Diceto recorded that Henry's sons "took up arms against their father at just the time when everywhere Christians were laying down their arms in reverence for Easter." (7)

William of Newburgh reported that "the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French King, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him". (8) Andrea Hopkins has argued that Eleanor identified more with the interests of her sons rather than those of her husband. (9)

One historian has pointed out that the brothers "were typical sprigs of the Angevin stock... they wanted power as well as titles". (10) Gerald of Wales quotes one of his sons, Geoffrey of Brittany, as saying: "It is our proper nature, planted in us by inheritance from our ancestors, that none of us should love the other, but that always, brother against brother and son against father, we try our utmost to injure one another?" (11)

Eleanor has been accused of being the ring-leader of the revolt against Henry: "It is clear that her sympathies lay wholeheartedly with her sons and that, like a lioness fighting to protect her cubs, she was prepared to resort to drastic measures to ensure that they received their just deserts... Henry and his brothers wanted autonomous power in the hands assigned to them, even if it meant the overthrow of their father; Eleanor wanted justice for her sons and, consequently, more power and influence for herself. This, she must have known, could only be achieved through the removal of her husband from the political scene." (12)

In a letter sent to Eleanor by Rotrou, Archbishop of Rouen, under the instructions of Henry II, he made it clear that he considered that his wife was behind the revolt as she had "made the fruits of your union with our Lord King rise up against their father". He added: "before events carry us to a dreadful conclusion, return with your sons to the husband whom you must obey and with whom it is your duty to live... Bid your sons, we beg you, to be obedient and devoted to their father." (13)

Eleanor's powerful lords from Aquitaine joined the rebellion. Henry the Younger also did a deal with William the Lion, the King of Scotland, who promised him Northumbria if he helped defeat his father. However, before the fighting began, Eleanor was captured by the agents of Henry. According to Gervase of Canterbury, Eleanor, left Poitiers for Chartres, on a horse, dressed as a man. She was recognized and arrested and taken to Henry who was based in Rouen. (14)

In July 1173 Henry defeated his sons at Verneuil Castle. His soldiers also had success against the Scots in Northumbria. His loyal commander, Richard de Lucy, defeated hired bands of Flemish mercenaries at Fornham, near Bury St Edmunds. (15) By the end of September 1174 it was all over. After their surrender, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey all had their allowances increased. Henry was formally assigned two castles in Normandy, to be chosen by his father, and 15,000 Angevin pounds for his upkeep. (16) However, all three sons had to promise never to "demand anything further from the Lord King, their father, beyond the agreed settlement... and withdrew neither themselves nor their service from him." (17)

John and Isabella of Gloucester

Henry decided to make arrangements for John. Only only seven-years-old he was granted annual revenues to the value of £1,000 from England and 1,000 livres each from Normandy and Anjou. In 1175, after the death of Reginald de Dunstanville, 1st Earl of Cornwall, the king reserved the earl's estates to John's use. This disinherited the earl's daughters and their husbands, who then rebelled. (18)

In 1176, John was betrothed to Isabella of Gloucester, the daughter of William Fitz Robert, 2nd Earl of Gloucester, and his wife Hawise. John and Isabella were half-second cousins as great-grandchildren of King Henry I. She was only a child at the time and so the marriage did not take place until 13 years later. (19) In May 1177 Henry designated John as king of Ireland. He was also given the title of count of Mortain and awarded the earldoms of Derby, Nottingham, Cornwall, Devon, Somerset and Dorset and numerous castles in the Midlands. (20)

In the autumn of 1183, King Henry II told Richard the Lionheart that he should give up Aquitaine to his youngest brother, John. In return, he would become heir to England, Normandy and Anjou. Richard refused as he believed as the eldest son left alive, he should inherit all his father's empire when he died. He also rejected the suggestion that another brother, Geoffrey, should be given Brittany to rule. (21) Henry now came up with another plan. He told Richard he would release his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, from prison, if he agreed to surrender his rights to Aquitaine. Richard, who was devoted to his mother, agreed to this suggestion. (22)

John married Isabella at Marlborough Castle on 29th August 1189. Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury, declared the marriage null by reason of consanguinity and placed their lands under interdict. (23) This was later lifted by Pope Clement III. The Pope granted a dispensation to marry but forbade the couple from having sexual relations. This seemed to be ignored but Isabella failed to produce any children. (24)

Richard the Lionheart

In January 1189, King Henry II became ill. From his sickbed he sent messages begging Richard the Lionheart to return to his side. However, he continued to fight alongside Philip II and he considered nominating his youngest son, John, as his heir. It is generally believed that Henry loved John more than his other sons. On 12th June Richard attacked Henry at his base in Le Mans. Henry was forced to flee and was taken to Chinon Castle. (25)

By the end of the month Maine was overrun and Tours had fallen. On 3rd July, Henry left his sickbed to meet Philip II at Ballan-Miré. He accepted his long list of demands including the confirmation of Richard as his heir in all lands on both sides of the Channel. Henry was so ill that the fifty-six year old king had to be held upright on his horse by his attendants. After signing the treaty he was too sick to ride and was carried home in a litter. On his return, Henry asked for a list to be drawn up of his former supporters who had joined Richard's rebellion. According to Gerald of Wales, the name at the top of the list was his favourite son John. (26)

Henry II died on 6th July 1189. Richard the Lionheart now became king of England. One of his first acts as king was to send William Marshal to England with orders to release his mother from prison. Richard also restored to her control the lands and revenues that she had enjoyed before the revolt of 1173. (27) Eleanor responded by toured England encouraging the barons to support her son and announced a general amnesty of prisoners. (28) Roger of Howden claims she went from "city to city and castle to castle", holding "queenly courts", releasing prisoners and exacting oaths from all freemen to "be loyal to her son as their as yet uncrowned king". (29)

Richard stayed in England only long enough to make the necessary financial arrangements for his involvement in the Third Crusade. This involved selling some of his recently acquired land. He even joked that he would sell London if he could find a buyer. (30) Roger of Howden claimed that "he (Richard) put up for sale all he had: offices, lordships, earldoms, sheriffdoms, castles, towns, lands, everything." (31)

According to Charles Scott Moncrieff: "Richard tended to regard England mainly as a piece of property from which, by taxes or other means, he could raise money for the Crusades. He got it chiefly in large lump sums from the wealthier people." Richard sold the Archbishop of York for £2,000. He put Ranulf de Glanville, the former Chief Justiciar of England and one of the richest men in the country, in prison and only released him when his family paid Richard £15,000. (32)

John met with Richard before he left England. King Richard gave his brother the title Count of Mortain and confirmed him Lord of Ireland. He also "bestowed on him other fiefs and castles, and assigned to him the entire royal revenues of six English counties, Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Derby and Nottingham". However, John was disappointed that the king had not given him any real power in administering England while he was away. (33)

On the way to the Holy Land, Richard married Berengaria of Navarre, the daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. William of Newburgh suggests that the marriage was arranged by Eleanor as she wanted him to have an "incontestable heir". (34) Walter of Guisborough claims that Richard had married Berengaria "as a salubrious remedy against the great perils of fornication". (35) The wedding was held in Limassol on 12th May 1191 at the Chapel of St. George. Richard took his new wife on crusade with him briefly but she returned home before Richard became involved in any fighting. The marriage did not produce any children. (36)

John now took the opportunity of Richard's absence to increase his power in England. Bishop William Longchamp, the justiciar whom Richard had left in charge of the kingdom, complained about John's behaviour. This included taking my force two castles. In April 1191, Richard sent Walter of Coutances back to England to deal with the problem. After lengthy negotiations, John agreed to relinquished the castles and Longchamp agreed to work to ensure John's succession to the throne in the event of Richard's death. (37)

On 8th June, 1191, Richard the Lionheart joined the army that had been besieging Acre for nearly two years. Saladin, the Muslim leader, attempted to take the besiegers' heavily fortified camp by storm was beaten back on 4th July. The exhausted defenders capitulated. Terms were agreed on 12th July: the garrison to be ransomed in return for 200,000 dinars and the release of 1,500 of Saladin's prisoners. (38)

Richard the Lionheart and his army headed for Jerusalem. Richard realised that if he managed to take the city, "they did not have the numbers to occupy and defend it especially since many of the most devout crusaders, having fulfilled their pilgrim vows, would at once go home". He decided to take Acre instead. Soon after this military success he heard rumours that John was involved in a plot with Philip II of France, to overthrow his government in England. (39)

Richard the Lionheart now reopened negotiations with Saladin so he could return to England. By now both sides were weary, and Richard himself fell seriously ill. A three-year truce was agreed on 2nd September. Richard had to hand back Ascalon; Saladin granted Christian pilgrims free access to Jerusalem. Many crusaders took advantage of this facility. "He had failed to take Jerusalem, but the entire coast from Tyre to Jaffa was now in Christian hands; and so was Cyprus. Considered as an administrative, political, and military exercise, his crusade had been an astonishing success." (40)

On his way home in December 1192, Richard was captured by Duke Leopold of Austria. Bishop Hubert Walter immediately began negotiating terms for Richard's release. In March 1193 Bishop Walter left for England carrying letters from the captive king concerning his ransom. Among these letters was the king's command to Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to have Hubert Walter elected archbishop of Canterbury. (41)

John and Philip II of France

When news of Richard's capture reached Philip II of France he suggested to John that they should take advantage of the situation. In January 1193 at Paris the two men signed a peace treaty which involved marrying Philip's sister, Alys. (42) In return, Philip promised to help him gain control of England. This included the attempt to persuade Duke Leopold to sell Richard to Philip for £100,000. (43)

John returned to England, seeking allies among those who traditionally took advantage of times when the English crown was in difficulties. Based at Windsor Castle he urged the magnates to join him in his rebellion. After summoning a council to condemn John and his followers, in February 1194, Hubert Walter, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, led the successful siege of Marlborough Castle and a few weeks later he personally accepted the peaceful surrender of Lancaster Castle. (44)

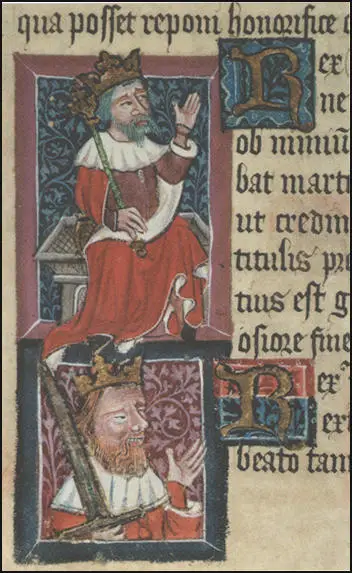

Thomas Walsingham's Golden Book of St Albans (1380)

Archbishop Walter urged Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine and the regency council to adopt a conciliatory policy towards John. He was not optimistic about Richard's chances of being released and if John became king he might exact vengeance on those who had opposed or offended him. He also pointed out that John's co-operation in raising ransom money from his tenants might be needed. Eleanor and the magnates took Hubert's advice and negotiated a truce with John. He agreed to surrender his castles to his mother and if they were unable to get Richard back, he would become king. (45)

Richard was not released until 4th February, 1194. According to the chronicler Roger of Howden, King Philip II of France wrote urgently to John to tell him the news. "Look to yourself, the devil is loose." (46) Richard landed in Sandwich on 20th March, having been away for nearly four years. Ralph de Diceto wrote that three days later "to the great acclaim of both clergy and people, he was received in procession through the decorated city of London into the church of St Paul's". (47)

Richard was upset with John and after he arrived back in England he seized his brother's most important castle at Nottingham and summonded John to appear before his Court within forty days in order to undergo judgment as a rebel. John refused and instead fled to France. (48)

Richard the Lionheart devoted the next five years to successfully recovering the territory he had lost while he was in prison. Having raised an army he travelled to Portsmouth with his mother and they set sail for the continent with one hundred ships on 12th May 1195. (49) Neither of them would ever set foot in England again. (50)

Richard and Eleanor travelled to Lisieux. They were joined by John who "falling at his feet... sought and obtained his clemency". Richard raised him up and gave him the kiss of peace, saying, "Think no more of it, John. You are but a child, and were left to evil counsellors. Your advisers shall pay for this. Now come and have something to eat". He then commanded that a gift of fresh salmon, be cooked and served to John. During the campaign John fought loyally beside his brother. (51)

In 1197 took back Normandy from King Philip II of France and "laid waste wide swathes of Philip's territories, plundering, burning, looting and killing; not even priests were spared." Many of the Philip's vassals declared for Richard, while others chose to remain neutral. Philip II was forced to accept defeat. (52)

On 25th March 1199, Richard arrived at Châlus-Chabrol, a small castle belonging to Aimar de Limoges. While walking around the castle perimeter without his chainmail, he was struck by a crossbow bolt in the left shoulder near the neck. Mercadier, his loyal lieutenant, attempted to remove the arrow head but "extracted the wood only, while the iron remained in the flesh... but after this butcher had carelessly mangled the King's arm in every part, he at last extracted the arrow." (53)

Within a day or so the wound grew inflamed and then putrid and Richard began to suffer the effects of gangrene and blood-poisoning. Richard knew he was dying and the man who fired the arrow, Bertram de Gurdun, was brought before him. Richard asked him why "you have killed me?" He replied: "You slew my father and my two brothers with your own hand... Therefore take any revenge on me that you may think fit, for I will readily endure the greatest torments that you can devise, so long as you have met with your end, having inflicted evils so many and so great upon the world." Richard was so moved and impressed with Gurdun's speech that he ordered him to be released. (54)

Richard named John as his heir before dying on 6th April 1199. Some sources claim that Mercadier took revenge on Gurdun and "first flayed him alive, then had him hanged". (55) However, Frank McLynn, the author of Lionheart & Lackland: King Richard, King John and the Wars of Conquest (2006) has pointed out that one source argues that Mercadier sent Gurdun to Richard's sister Joan, "who put him to death in some gruesome way." (56)

King of England

John now became the new king of England. As Stephen Church, the author of King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant (2015) has pointed out: "He was duke of Normandy and of Aquitaine, and count of Anjou. In addition, he enjoyed rulership of the kingdom of Ireland, overlordship of Wales, Scotland and Brittany, and claimed overlordship of the county of Toulouse." (57)

John's mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, played an important role in ensuring he was accepted as king. Although she was now 77 years old she travelled throughout Aquitaine during the early summer, granting privileges to churches and urban communities as well as negotiating with the regional aristocracy to give their support to John. It has been estimated that she travelled over 1,000 miles during this period. (58)

England and Normandy accepted John succession without protest. However, the barons of Anjou, Maine and Touraine, refused to accept him as their ruler and instead declared for Arthur of Brittany, Eleanor's grandson (the son of Geoffrey). Eleanor was outraged and ordered that Anjou be laid waste as a punishment for its support of Geoffrey. Her soldiers attacked Angers and sacked the city. (59)

At the end of 1199 Eleanor set off from Poitiers to visit King Alfonso VIII of Castile who had married her daughter, Eleanor. Soon after the beginning of her trip she was ambushed by her vassal, Hugh IX le Brun, and taken prisoner. He demanded the return of land taken from the family by Henry II and retained by Richard the Lionheart. Eleanor accepted his family had been badly treated and granted him the disputed territory of La Marche. (60)

Eleanor crossed the Pyrenees in the depths of winter and reached Toledo at the end of January, 1200. King Alfonso was the father of twelve children, and two of his daughters, Urraca and Blanche, were unmarried. Eleanor decided to arrange for her two grand-daughters to marry members of Europe's royal family. Blanche (12 years old) married King Louis VIII of France and Urraca (13 years old) married King Alfonso II of Portugal. (61)

King John's marriage to Isabella, Countess of Gloucester, failed to produce any children and made plans to divorce his wife. However, Stephen Church, the author of King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant (2015), a more important reason was to marry someone who would help increase the size of his kingdom. (62) With the encouragement of Eleanor, the marriage was annulled and he married Isabella of Angoulême on 24th August, 1200. At the time of her marriage to John, the blonde and blue-eyed 12-year-old Isabella was already renowned by some for her beauty. John was "madly enamoured" with his bride, as "he believed he possessed everything he could desire". (63)

Isabella, was originally betrothed to Hugh IX le Brun, Count of Lusignan. He protested against the sudden loss of his fiancée and when he got no justice from King John he appealed to the court of Philip II of France, who "declared in his favour and ruled all of John's "continental fiefs forfeit". John now invaded France and initially had some success and on 1st August 1202 he was able to capture Arthur of Brittany, one of the leaders of the rebels in Normandy. More than 250 knights were chained together and then paraded as trophies before being taken to prisons in England and Normandy. (64)

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagenets (2013) has argued that "John's military campaign was the most complete and stunning victory won by forces under an English king since Richard had relieved Jaffa in 1192. At a stroke, John had decapitated the Lusignan resistance in Aquitaine... John was careful to rub it into the noses of everyone he passed slowly on his way back to Normandy. His illustrious prisoners were paraded, heavily manacled, as a public warning of the consequences of rebellion." (65)

Arthur and other rebels were kept in terrible conditions. William Marshal, who had supported John as king was highly critical about the way he treated the prisoners: "The king kept his prisoners in such a horrible manner and such abject confinement that it seemed an indignity and a disgrace to all those with him who witnessed his cruelty." At Corfe Castle twenty-two of these prisoners starved to death. (66)

Arthur of Brittany was shut up in a dungeon in Falaise Castle and was never seen alive again. Roger of Wendover reported: "Opinion about the death of Arthur gained ground, by which it seemed that John was suspected by all of having slain him with his own hand; for which reason many turned their affections from the King and entertained the deepest enmity for him." (67)

The people of France were horrified by the idea that John had executed the 16-year-old Arthur. The lords of Maine defected to King Philip and Le Mans fell to the French. In Brittany, Arthur's subjects rose in revolt and this cut Normandy off from Poitou. King Philip advanced along the Loire and took the great fortress of Saumur. "Chinon held out against him, so he swung north and marched unopposed into Normandy, taking town after town: Domfront, Coutances, Falaise, Bayeux, Lisieux, Caen and Avranches - those great bastions of Angevin power - all fell to him." (68)

In December 1203, John decided to abandon France and left his officials to make the best terms they could. A month later, Angers, was captured. There was also a serious rebellion against his rule in Aquitaine. One of his officials wrote that John "saw his land getting worse by the day as a result of war, and Frenchmen who had no love for him and pillaged his land". By the summer of 1205 the last of his strongholds in Normandy and Anjou had fallen. These humiliating military defeats earned John a new nickname; he became known as "Softsword". (69)

Before he married Isabella of Angoulême, John had a large number of mistresses and at least seven illegitimate children. It was not until October 1207 did Isabella bear her first child, Henry. This was followed by the birth of Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, (1209), Joan (1210), Isabella (1214) and Eleanor (1215). John never gave Isabella the landed endowment that a queen expected. In consequence she played no political role in England. (70)

King John: An Assessment

The historian, William Stubbs, has argued that John was the "worst of all our kings" and before he obtained power he showed he was "a faithless son and a treacherous brother". Stubbs claims that he had great difficulty forming alliances: "John had made private enemies as well as public ones; he trusted no man, and no man trusted him. The threat of deposition aroused all his fears, and he betrayed his apprehensions in the way usual with tyrants." (71)

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagenets (2013), agrees with this assessment. He claims that his early behaviour, when he betrayed his father and his brother, meant that he was not trusted: "Neither princes nor bureaucrats were fully inclined to believe him or to believe in him, and frequently this was with good reason. John's career to 1199 was pockmarked by ugly instances of treachery, frivolity and disaster, since his earliest, unwitting involvement in the dynastic politics of the Plantagenet family as John Lackland his father's coddled favourite, until his covetous behaviour during his brother's long captivity." (72)

Writers such as Dan Jones rely heavily on 13th century historians such as Matthew Paris, who was extremely hostile to King John. Paris wrote: "John was a tyrant rather than a king, a destroyer rather than a governor, an oppressor of his own people, and a friend to strangers, a lion to his own subjects, a lamb to foreigners and those who fought against him... he was an insatiable extorter of money, and an invader and destroyer of the possessions of his own natural subjects... he had violated the daughters and sisters of his nobles; and was wavering and distrustful in his observance of the Christian religion?" (73)

William of Newburgh claimed that John was "a very foolish youth". (74) Roger of Wendover suggested that John was "a worse man than many who have done more harm". (75) Gerald of Wales, who did have some first-hand knowledge of John as a teenager, wrote: "Caught in the toils and snared by the temptations of unstable and dissolute youth, he was as wax to receive impressions of evil, but hardened against those who would have warned him of its danger; compliant to the fancy of the moment; more given to luxurious ease than to warlike exercises, to enjoyment than to endurance, to vanity than to virtue." (76)

Maurice Ashley has pointed out that medieval historians were not always very accurate in their writings: "The monastic chroniclers... have been shown by modem research to be completely unreliable in what they said about John, because their works were largely compiled out of gossip and rumour directed against a monarch who had upset the Church... King John was... a first-class general, a clever diplomat and a ruler who developed... English law and government." (77)

Alison Weir supports this view and compares John's record with his brother, Richard the Lionheart and his father, Henry II: "Unlike his brother Richard, he showed real concern for his kingdom, and travelled more widely within it than any of his Norman and Angevin predecessors, dispensing justice and overseeing public spending." Weir points out that "recent studies of the official documents of his reign have shown that he was a gifted administrator who showed a concern for justice" and during "his reign, as a result of his personal intervention, the Exchequer, Chancery and law courts began to function more effectively". Finally, the "records also suggest that the King took a more than ordinary interest in the welfare of his common subjects". (78)

One of his biographer's Thomas K. Keefe, admits that King John was guilty of acts of cruelty, deviousness, and betrayal, but this was not that unusual behaviour of monarchs during this period. John's main problem was that while he was king the country lost a succession of military conflicts: "Although sporadically capable of effective military action, a king believed to be soft, cowardly, and untrustworthy was incapable of winning a war". (79)

Conflict with Pope Innocent III

Hubert Walter, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died on 13th July 1205. King John decided that he had the right to appoint his replacement. He selected John de Grey, the Bishop of Norwich, who was an experienced legal clerk, judge and diplomat who had previously served as John's secretary. The chapter of clerics at Canterbury, claimed they had the right to elect the new archbishop. They opposed Grey in favour of their own man, Reginald. (80)

When news reached Pope Innocent III in Rome he was outraged. He believed strongly that he had ultimate sovereignty over Europe's kings. The Pope overturned Gray's election in March 1206. He also rejected Reginald's candidacy and put forward his own candidate, Cardinal Stephen Langton, who was a theologian and completely loyal member of the Church hierarchy. Langton was consecrated by the Pope on 17th June 1207. (81)

King John reacted by sending a letter to the Pope where he threatened to stop the papacy from using English ports. He followed this up with declaring "Langton an enemy of the Crown, and took the possessions of the See of Canterbury into royal custody." Innocent III responded on 23rd March 1208, by placing the whole of England under Interdict. This meant that all church services were forbidden to be held. (82) He also decreed that anyone calling Langton archbishop was guilty of high treason. (83)

The following year he excommunicated King John and offered negotiations to deal with the problem. However, John refused and all churches remained closed. John now seized the estates of the clergy and many of the bishops fled from the kingdom. It is being claimed that this was worth about 20,000 marks a year. Hostility towards King John increased and Roger of Wendover, a monk from St Albans Abbey, announced that he had "a vision has revealed to me that the king shall not rule more than fourteen years, at the end of which time he will be replaced by someone more pleasing to God." (84)

In 1211 the Pope declared that unless the King "would submit he would issue a bull absolving his subjects from their allegiance, would depose him from his throne, and commit the execution of the mandate to Philip of France." (85) As the result of these comments Philip II of France announced an invasion of England in April 1213. John stationed a large army in Kent but on 15th May, he decided to surrender his kingdom to the papacy and promised to pay an annual tribute of 1,000 marks. Many people saw this as a humiliating servitude, but others have praised John for carrying out a master stroke of diplomacy. "Although negotiations over payment of compensation meant that not until July 1214 was the interdict finally lifted, it none the less immediately converted Innocent into his most ardent defender and so - much to Langton's disquiet - John was able to promote his own clerks to vacant bishoprics". (86)

King John now decided to make another attempt at gaining control on his lost territory in France. In February 1214, he sailed from Portsmouth for La Rochelle, in a ship carrying numerous English nobles, as well as Queen Isabella of Angoulême and their five-year-old son, Richard. The campaign began well and his soldiers seized Poitou, Nantes and Angers. However, he suffered defeats at Roche-au-Moine (2nd July) and Bouvines (27th July). King John was forced to sign a five-year truce with King Philip at a price that was believed to be in the region of £40,000. (87)

The Magna Carta

King John returned to England as a discredited monarch. The only patch of territory in mainland France that remained loyal to the English Crown was Gascony and the area around Bordeaux. The historian, Frank McLynn, has argued that his military defeat in France caused John serious problems: "Having given up (or been forced to give up) their Norman lands, the new barons domiciled in England had more time to concentrate on the affairs of the island, with unpleasant consequences for John." (88)

When John tried to obtain this money by imposing yet another tax, the barons rebelled. Few barons remained loyal, and in most areas of the country, John had very little support. In January 1215 the king met his opponents at London - they came armed - and it was agreed that there should be another meeting in the near future. On 15th June, 1215, at Runnymede, King John was forced to accept the peace terms of his opponents. (89) As one historian pointed out: "The leaders of the barons in 1215 groped in the dim light towards a fundamental principle. Government must henceforward mean something more than the arbitrary rule of any man, and custom and the law must stand even above the King." (90)

The document the king was obliged to sign was the Magna Carta. In this charter the king made a long list of promises, including: (I) The English Church shall be free... freedom of elections, which is reckoned most important and very essential to the English Church. (II) If any of our earls, or barons... shall have died, and at the time of his death his heir shall be of full age... he shall have his inheritance. (VII) A widow, after the death of her husband, shall without difficulty have her inheritance. (VIII) No widow shall be compelled to marry, so long as she prefers to live without a husband. (XII) No scutage or aid (tax) shall be imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our kingdom. (XIV) And for obtaining the common counsel of the kingdom before the assessing of an aid or of a scutage, we will cause to be summoned the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and greater barons."

Most of the terms of the charter dealt with the rights of the barons and those who were wealthy. However, there were some clauses that concerned ordinary people: (XX) "A freeman shall not be fined for a slight offence... and for a grave offence he shall be fined in accordance with the gravity of the offence... and a villein should be fined in the same way. (XXIII) No village or individual shall be compelled to make bridges or river banks. (XXX) No sheriff or bailiff... or other person, shall take the horses or carts of any freeman for transport duty, against the will of the said freeman. (XXXIX) No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or outlawed or exiled or in anyway destroyed... except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land. (XL) To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse justice. (XLII) It shall be lawful in future for anyone to leave our kingdom... excepting those imprisoned or outlawed in accordance with the law in the kingdom." (91)

Stephen Church, the author of King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant (2015) has pointed out that in reality it was a peace treaty but it was important to King John to describe it as a charter: "The barons might have forced John to make concessions about how he would rule, but no king could allow himself to be seen to capitulate to his subjects; he was, after all, set over them by God... The terms of Magna Carta were, therefore, couched in the form of a grant from a benevolent king to his faithful subjects." (92)

In July 1215, King John secretly wrote to Pope Innocent III asking him to annul the charter. Early in September the arrival of papal letters excommunicating the rebels, gave him the confidence to declare war on the Barons. He now denounced the charter and his troops laid siege to Rochester Castle. The rebels responded by offering the throne to Prince Louis, the young son of Philip II of France. In May 1216 Prince Louis invaded and made an unopposed entry into London. (93)

King John died of dysentery on 19th October 1216. His son Henry was only nine-years-old and the supporters of Louis quickly deserted to the young prince. He was crowned, and the government was carried on in his name by a group of barons led by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. They made sure that the principles of the Magna Carta came to be accepted as the basis of the law. (94)

Primary Sources

(1) The Margam Abbey Chronicle (c. 1205)

King John had captured Arthur and kept him alive in prison for some time in the castle of Rouen... After dinner on the Thursday before Easter when he was drunk and possessed by the Devil, King John killed him with his own hand, and tying a heavy stone to the body cast it into the Seine.

(2) The Barnwell Abbey Chronicle (c. 1220)

He (King John) was generous and liberal to outsiders but stole from the English. Since he trusted more in foreigners than in the English, he had been abandoned before the end by his people, and his own end was little mourned.

(3) Matthew Paris, Greater Chronicle (c. 1260)

John was a tyrant rather than a king, a destroyer rather than a governor, an oppressor of his own people, and a friend to strangers, a lion to his own subjects, a lamb to foreigners and those who fought against him; for, owing to his slothfulness, he had lost Normandy and, moreover, was eager to lose the kingdom of England or destroy it; he was an insatiable extorter of money, and an invader and destroyer of the possessions of his own natural subjects... he had violated the daughters and sisters of his nobles; and was wavering and distrustful in his observance of the Christian religion?

(After signing the Magna Carta) King John's mental state underwent a great change... He started to gnash his teeth and roll his eyes in fury. Then he would pick up sticks and straws and gnaw them like a lunatic... His uncontrolled gestures gave indications... of the madness that was upon him.

(4) Gerald of Wales, Concerning the Instruction of a Prince (c. 1190)

Caught in the toils and snared by the temptations of unstable and dissolute youth, he was as wax to receive impressions of evil, but hardened against those who would have warned him of its danger; compliant to the fancy of the moment; more given to luxurious ease than to warlike exercises, to enjoyment than to endurance, to vanity than to virtue.

(5) William Stubbs, Constitutional History of England (1875)

John had made private enemies as well as public ones; he trusted no man, and no man trusted him. The threat of deposition aroused all his fears, and he betrayed his apprehensions in the way usual with tyrants.... John was the worst of all our kings... a faithless son and a treacherous brother... polluted with every crime... in the whole view there is no redeeming trait.

(6) John Gillingham, The Lives of the Kings and Queens of England (1975)

John possessed some good qualities. Few kings took such a close interest in the details of administration and the daily business of the law courts, but in his own day this counted for very little. John was suspicious of other men and they of him. He inspired neither affection nor loyalty and once he had shown that, no matter how hard he tried, he lacked Richard's ability to command victory in war, then he was lost.

(7) Maurice Ashley, Life and Times of King John (1972)

The monastic chroniclers... have been shown by modem research to be completely unreliable in what they said about John, because their works were largely compiled out of gossip and rumour directed against a monarch who had upset the Church... King John was... a first-class general, a clever diplomat and a ruler who developed... English law and government.

(8) Stephen Church, King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant (2015)

He (King John) had started his reign as the de facto ruler of not only England, but also large parts of what would become the kingdom of France. He was duke of Normandy and of Aquitaine, and count of Anjou. In addition, he enjoyed rulership of the kingdom of Ireland, overlordship of Wales, Scotland and Brittany, and claimed overlordship of the county of Toulouse. By 1204, he had lost Normandy, Anjou and the northern part of Aquitaine (called Poitou and centred on Poitiers), though he still held the southern part (called Gascony and centred on Bordeaux). By his death, John had lost control of London (his capital city), of Westminster (where his Exchequer sat), of the south of England (to the French who had invaded under the leadership of Louis, son of the French king), and he had enemies in the north and in the east of his kingdom.

(9) Dan Jones, The Plantagenets (2013)

John did not inspire confidence. This was perhaps his defining characteristic. Neither princes nor bureaucrats were fully inclined to believe him or to believe in him, and frequently this was with good reason. John's career to 1199 was pockmarked by ugly instances of treachery, frivolity and disaster, since his earliest, unwitting involvement in the dynastic politics of the Plantagenet family as "John Lackland" his father's coddled favourite, until his covetous behaviour during his brother's long captivity. John's behaviour during the latter years of Richard's reign had been broadly good, but it did not take much to recall how appallingly he had acted while Richard was out of the country. John had rebelled against Richard's appointed ministers, interfered with ecclesiastical appointments, connived at the destruction of the justiciar William Longchamp, encouraged an invasion from Scotland, spread the rumour that his brother was dead, entreated Philip II to help him to secure the English throne for himself, done homage to Philip for his brother's continental lands, granted away to Philip almost the whole duchy of Normandy, attempted to bribe the

German emperor to keep his brother in prison, and almost single handedly created the feeble state in which Richard had found the Plantagenet lands and borders on his eventual release from captivity.And these were only the political facts. The personal perception was worse. Although John had been quiet and dutiful in his service to Richard following their reconciliation in 1195, he was still thought by many to be untrustworthy. Contemporary writers also commented on John's unpleasant demeanour, which seemed dark in opposition to the brilliant glow of chivalry that emanated from his brother. Like Richard and Henry II, John was already known for his tough financial demands and fierce temper. Like Henry he was thought to be cruel, and he tended to make vicious threats against those who thwarted him. Unlike Henry and Richard, however, he was also weak, indecisive and unchivalrous. Several writers noted that John and his acolytes sniggered when they heard of others' distress. He was deemed untrustworthy, suspicious, and advised by evil men.

(10) Alison Weir, Eleanor of Aquitaine (1999)

On 25 May 1199, confident that his continental possessions were secure for the moment, John crossed to England to claim his kingdom... As King of England, John has received a bad press, although recent studies of the official documents of his reign have shown that he was a gifted administrator who showed a concern for justice... Unlike his brother Richard, he showed real concern for his kingdom, and travelled more widely within it than any of his Norman and Angevin predecessors, dispensing justice and overseeing public spending. During his reign, as a result of his personal intervention, the Exchequer, Chancery and law courts began to function more effectively. The records also suggest that the King took a more than ordinary interest in the welfare of his common subjects.

(11) Thomas K. Keefe, Henry II : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

He (King John) instructed keepers of castles and prisoners not to hand over their charges when they received written orders to do so, unless those orders were accompanied by a prearranged sign - though he sometimes forgot what the sign was. So devious a man was inevitably distrusted, even at the start of his reign - as when Arthur fled his court in 1199. Men such as William the Lion and Stephen Langton had no confidence in his safe conducts, unless they were supported by an imposing array of prelates and barons.... Although sporadically capable of effective military action, a king believed to be soft, cowardly, and untrustworthy was incapable of winning a war.

Two authors writing in the 1220s, the Barnwell chronicler and Roger of Wendover, were to be very influential. Historians who have taken a relatively positive view of John have turned for support to the Barnwell chronicler's judgement that "though he enjoyed no great success and, like Marius, met with both kinds of luck, he was certainly a great prince". Historians who have taken a hostile view of John have preferred Roger of Wendover's account, particularly when enlivened by some of Matthew Paris's additions. With a few exceptions such as the relatively neutral Ranulf Higden (though even he blamed John for the death of Arthur of Brittany and for the loss of his dominions), historians writing before the Reformation tended to follow the views of Wendover and Paris.

Student Activities

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

King John and the Magna Carta (Answer Commentary)

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

Richard the Lionheart (Answer Commentary)

The Peasants' Revolt (Answer Commentary)

Death of Wat Tyler (Answer Commentary)

Medieval Historians and John Ball (Answer Commentary)

Taxation in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)