William the Conqueror

William, the illegitimate son of Robert, Duke of Normandy and Herleva of Falaise, was born in 1027. His mother was the daughter of a tanner. It was claimed that Robert fell in love with Herleva when he saw her doing the washing in the stream which passed her father's tannery at the foot of Falaise Castle. (1)

Instead of marrying Herleva, Robert persuaded her to marry his friend, Herluin de Conteville. Robert had great difficulty controlling his territory. William of Jumieges claims that there was regular conflict between the Norman rulers and their neighbours and records that Robert fought wars against his cousin, Alan of Brittany and his uncle, Count of Evreux. (2)

In 1034 Robert summoned a meeting of the Norman magnates and persuaded them to recognise William as his son and heir. King Henry I of France, the overlord of the Dukes of Normandy, gave his consent to the decision. Robert then set out on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. According to Ordericus Vitalis he died on his return journey at Nicaea on 2nd July 1035. (3)

William therefore became duke of the Normans at the age of eight. He was brought up by his mother, who by this time had given birth to two more sons, Odo of Bayeux and Robert of Mortain. Two of William's uncles tried to gain control of Normandy. Others also made claims and for several years there was anarchy in the region but fortunately for him, the protagonists were either killed or conveniently died. (4) John Gillingham has argued he only survived because of his "mother's kinsman." (5)

William, Duke of Normandy

In 1046 a full-scale rebellion began in western and middle Normandy headed by Guy of Burgundy. An attempt was made to kill William and he asked for help from the King Henry. William of Poitiers reports that William and his soldiers managed to defeat Burgundy and "dismantled the ramparts of crime by victoriously recapturing many castles and thus stopped for a long time the intestinal wars in our region." (6)

William then went to war against Geoffrey Martel, the Count of Anjou. When the town of Alencon refused to surrender to the Normans, William ordered that 34 prisoners should have their eyes removed and their hands and feet cut off in front of the town gates. William then threatened to do the same to all the men in the town unless they surrendered immediately. (7)

Tactics such as these were successful and William soon gained a reputation as a dynamic and cruel war-leader. Henry I, the French king became worried about the increasing power of William and in 1054 he invaded Normandy. After pretending to retreat, the Normans took the French by surprise at Mortemer and King Henry was forced to withdraw. William then increased the area under his control by taking the neighbouring territory of Maine.

There was now a danger that all William's enemies would join together against him. He needed allies and he obtained these through marriage. First he arranged for his sister to marry the Count of Ponthieu. Then he obtained the support of Count Baldwin V of Flanders by offering to marry his daughter, Matilda of Flanders. Pope Leo IX forbade the marriage on the grounds that William and Matilda were too closely related. Despite this William went ahead with his plans. (8)

William had not met Matilda when he arranged the marriage. It was said that they looked strange together as William was nearly 6 feet tall while Matilda was only 4 feet 2 inches tall. The little evidence that we have suggests that they were happy together and during the next sixteen years Matilda had at least nine children. This included Robert Curthose, Richard, Adeliza, Cecilia, William Rufus, Constance, Adela and Henry Beauclerk. He appears to have been completely faithful husband, maybe because he wanted to avoid illegitimate children. (9)

A Benedictine monk pointed out: "William, Duke of Normandy, never allowed himself to be deterred from any enterprise because of the labour it entailed. He was strong in body and tall in stature. He was moderate in drinking, for he deplored drunkenness in all men. In speech he was fluent and persuasive, being skilled at all times in making clear his will. He followed the Christian discipline in which he had been brought up from childhood, and whenever his health permitted he regularly attended Christian worship each morning and at the celebration of mass." (10)

According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward the Confessor promised William that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, the father of Edward's wife, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. (11)

In a series of battles William defeated his overlord, King Henry I of France, Geoffrey Martel, the Count of Anjou and the Hoel II, Duke of Brittany. In 1063 he increased his territory by taking control of Maine. (12) He also established control over the Church in Normandy. William appointed his uncle, Mauger, as Archbishop of Rouen. William also established twenty new monasteries in Normandy. Although he attempted to develop a good relationship with Pope Alexander II, he insisted on nominating his own bishops and abbots. (13)

Christopher Brooke has argued that over the years William had developed all the qualities needed to be a successful leader: "Some of William's qualities were matured and hardened early in the tough school in which he grew up. He learned to be forceful, and firm; to be ruthless, but to avoid needless violence; he learned that he could only trust the Norman barons when they feared him. Skill in arms, a taste for the hunting field, an interest in military techniques, all came young. But some of his most striking qualities and interests grew slowly to maturity. He was certainly a man of imagination; but his ideas did not come by swift intuition. They came slowly, by experience carefully reflected on; they bore fruit, because William, for all his prudence, was lavishly endowed with moral courage." (14)

The Death of Edward the Confessor

In 1064 Harold of Wessex was on board a ship that was wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and imprisoned at Beaurain. William, demanded that Count Guy release him into his care. Guy agreed and Harold went with William to Rouen. William later explained what happened: "Edward sent Harold himself to Normandy so that he could swear to me in my presence what his father, Earl Godwin and Earl Leofric (Mercia) and Earl Siward (Northumbria) had sword to me here in my absence. On the journey Harold incurred the danger of being taken prisoner, from which, using force and diplomacy, I rescued him. Through his own hands he made himself my vassal and with his own hand he gave me a firm pledge concerning the kingdom of England." (15)

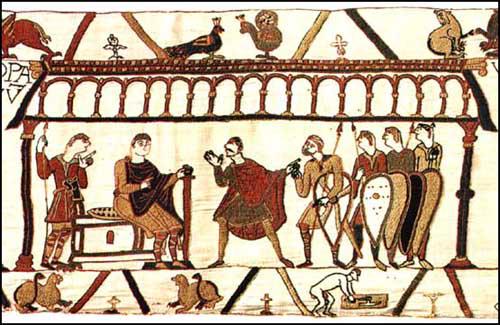

Godwinson (with mustache) in 1064 Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1090)

In 1065 Edward the Confessor became very ill. Harold claimed that Edward promised him the throne just before he died on 5th January, 1066. (16) The next day there was a meeting of the Witan to decide who would become the next king of England. The Witan was made up of a group of about sixty lords and bishops and they considered the merits of four main candidates: William, Harold, Edgar Etheling and Harald Hardrada. On 6th January 1066, the Witan decided that Harold was to be the next king of England. (17)

Preparations for Invasion

William of Normandy immediately began making preparations for an invasion of England. This included convincing the Norman aristocracy that it was possible to defeat the much feared English navy and army. William of Malmesbury points out that the first meeting with the Norman lords took place at Lillebonne. (18) At first only a minority believed in the success of such a venture whereas the majority thought that "a handful of Normans could not conquer a huge multitude of Englishmen". (19)

Another meeting was held at Bonneville-sur-Touques in June, 1066. According to the Norman historian, William of Poitiers, it was William Fitz Osbern who eventually persuaded them the adventure was practicable. (20) His main supporters were Robert of Mortain, Odo of Bayeux and Richard Fitz Gilbert. Other important figures were Roger of Beaumont and Roger of Montgomery, who agreed to remain in Normandy to protect if from possible invasions. By the end of negotiations the Norman nobility were eager to support an extremely hazardous enterprise, and even to stake their personal fortunes on its success". (21)

It has been pointed out that William's navy was very small and was certainly was completely inadequate to transport a large invading force. Peter Rex claims that his navy "had to be built from scratch, as Normandy had no fleet". (22) William of Jumieges claims that the Normans assembled 3,000 ships. (23) Other Norman sources suggest it was more like 700 ships. This number would have been needed to carry the numbers of soldiers and horses that were said to have been used in the forthcoming battle. (24)

Some historians have doubted if this figure is correct. As Frank McLynn has pointed out: "One estimate is that it would take 8,400 men to build 700 ships, with 6,900 peasants working non-stop to feed them." These are resources that were not available to William and therefore "the overwhelming likelihood is that William simply requisitioned all existing craft in Norman ports and purchased most of the rest of his vessels from Flanders." (25)

Even with the support of his Norman barons William still did not have enough soldiers to defeat Harold. He therefore had to enter into negotiations with the rulers of Flanders, Brittany, Aquitaine and Boulogne, who not only agreed to supply men but promised not to invade Normandy while he was away. William also arranged for soldiers from Denmark and Italy to join his army. He also got support from Emperor Henry IV, the king of the Germans, who "entered into a new friendship so that an edict was issued by which Germany might come to his aid if he asked for it against any enemy". (26)

William also carried out talks with Pope Alexander II. It is claimed by William of Poitiers that William had papal support for his invasion. There are two very good reasons that this might have been true. William promised that he would grant 25% of England to the Church. Alexander was also very angry with the English throne for appointing Stigand as Archbishop of Canterbury without papal approval. (27)

William of Malmesbury states that the Pope gave a "standard" to carry into battle. (28) This has been rejected by some historians who consider him an unreliable source. They point out nowhere in the Bayeux Tapestry is there any reference to the Pope, nor has the papal banner been identified with certainty amongst the many flags embroidered on this valuable source on the invasion. (29)

On 4th August 1066, William assembled his men at Dives-sur-Mer in Normandy. Historians have disagreed about the size of William's army. "The most likely figure is 14,000, of which 8,000 would be used in battle, 2,000 on garrison duties, another 4,000 sailors and non-combatants (oarsmen, helmsmen, pilots, cooks, armour-bearers, smiths, carpenters, artisans, clerics, monks) and 3,000 horses... To sustain 14,000 men and 3,000 horses for a month the Normans would have needed 2,340 tons of grain (two-thirds of this for horses) plus 1,500 tons of straw and 155 tons of hay." (30)

According to Philippe Contamine, the author of War in the Middle Ages (1986) argues special care had to be taken with warhorses as they were perceived as the key to military success. They needed shelter if they were to remain in good condition. Their minimum daily ration would be twelve pounds of grain (oats or barley) and thirteen pounds of hay per horse. Warhorses would have to be kept in good condition if they were to carry 250 lbs of rider and equipment into a battle that might last all day and involve uphill charges. (31)

William of Poitiers argues that William of Normandy insisted that his men treated the local people with respect and "utterly forbade pillage". To make sure his instructions were followed "he made generous provisions both for his own knights and for those from other parts" and "did not allow any of them to take their sustenance by force". As a result the "herds of the peasantry pastured unharmed throughout the province." (32)

Harold II of England fully expected a Norman invasion. It was claimed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that by June 1066 he had "gathered such a great naval force, and a land force also, as no other king in the land had gathered before." (33) Harold placed his navy and some of the soldiers on the Isle of Wight. The rest of his soldiers were spread along the Sussex and Kent coast. "The object of this arrangement was that in the event of a landing the lookouts on the coast would signal the arrival of the enemy (probably by lighting a beacon) and Harold would then sail from the Isle of Wight with his army to fall upon the invaders". The reason for this is that the prevailing wind, particularly during the summer months, is from the south-west. "It was more than likely that the wind that would carry the invading fleet would be the same upon which Harold would sail, to land behind the invaders or on an adjacent beach." (34)

Harold's soldiers were made up of housecarls and the fyrd. Housecarls were well-trained, full-time soldiers who were paid for their services. The fyrd were working men who were called up to fight for the king in times of danger. All earls had their own housecarls and Harold had a substantial force at his disposal. They were paid mercenaries and were equally adept in land and maritime warfare. (35)

Meanwhile, Tostig was negotiating with King Harald Hardrada about a possible invasion. Eventually the reached an agreement to attack Harold. After appointing his son, Magnus as regent he formed alliances with warriors from Iceland and Ireland. Tostig also convinced Hardrada that Harold was extremely unpopular in the north of England and that people living in this region would join them in their attempt to overthrow the king of England. (36)

Harold waited all summer but the Normans did not arrive. Never before had any of Harold's fyrd been away from their homes for so long. But the men's supplies had run out and they could not be kept away from their homes any longer. Members of the fyrd were also keen to harvest their own fields and so in the first week of September 1066, Harold sent them home. The sailing season was also drawing to a close for the year. Harold therefore decided to arrange for his navy to travel along the Thames to London to enable essential repairs to be carried out. Harold, after a short stay at his home in Bosham, rode to the capital with his housecarls. (37)

On 12th September, 1066, the Norman fleet left Dives-sur-Mer for Saint-Valery, to take advantage of the shorter sea-crossing. (38) It is also possible that he had received information from his spies in England that the Sussex coast was now undefended and that he had abandoned his plan to land in Hampshire and march on Winchester, the capital of Wessex. (39) Once in the open sea the ships took a battering from south-west winds and "William was said to have buried hundreds of bodies of the drowned secretly, so as not to affect morale". (40)

Battle of Stamford Bridge

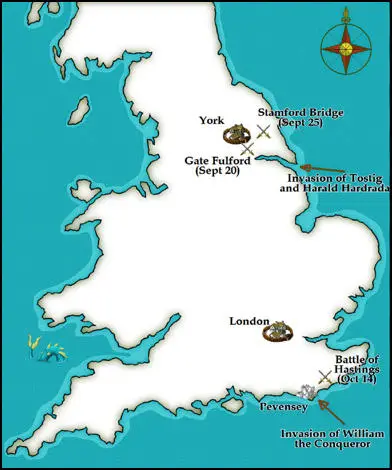

William of Normandy was unaware that In the first week of September, 1066, an army led by King Harald Hardrada of Norway and Tostig, the former Earl of Northumbria, and King Harold's younger brother, raided Scarborough and slaughtered most of its inhabitants. Sailing on, the fleet entered the Humber estuary. Morcar, the Earl of Northumbria, and Eadwine, Earl of Mercia, were not willing to engage the enemy and retreated before him up the Ouse, before turning into the inland waters of the Wharfe to Tadcaster. Hardrada anchored at Riccall. After leaving a substantial force to guard the fleet, Hardrada, Tostig and about 6,000 men marched on York. (41)

On 20th September, Morcar and Eadwine went into battle with Hardrada and Tostig at Fulford Gate. It has been estimated that the Norwegians had about 6,000 troops and the defenders 5,000. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle "many of the English were slain, drowned or put to flight and the Northmen had possession of the place of slaughter". (42)

Other sources say casualties were high on both sides but it is clear that the invaders had a clear victory. (43) According to one source: "Trying to escape the pincer movement, the English veered away into the marsh, where they foundered in the bog until cut down or sucked into quicksands; those who tried flight on the other side mostly drowned in the Ouse. Soon the marsh and the ditches were clogged with human bodies, to the point where the Norwegians waded in blood and marched over the impacted corpses as if on a solid causeway." (44)

Hardrada then moved onto York, which formally surrendered on 24th September. Hardrada took 150 children hostage from prominent families in Yorkshire as surety for their loyalty. Morcar and Edwin and the remnants of their army escaped into the countryside. The Norwegians now withdrew to Stamford Bridge, a place where several Roman roads met. The bridge would have been quite large by eleventh-century standards. (45)

It has been claimed that a messenger told Harold about the Norwegian victory at Fulford Gate he said that Hardrada had come to conquer all of England. Apparently Harold replied: "I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet." Harold then sent a summons for the men of the fyrd to reassemble, just days after they had been released from their long summer vigil. Having gathered as many of his men as he could he started for the north on about the 19th September. (46)

Harold and his English army marched 190 miles from London to York. The historian, Frank McLynn, the author of 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999), has commented "the speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting." (47)

Peter Rex argues in Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005) that his housecarls were on horseback: "Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep." (48)

On 25th September Harold's army arrived at Stamford Bridge. Harold and twenty of his housecarls rode up to the foot of the bridge on the left bank of the Derwent and had a meeting with Tostig. Harold promised his brother that if he changed sides he would be rewarded with the return of his earldom and one-third of all England. Tostig answered that it would never be said of him that he brought the king of Norway to England only to betray him. He turned on his horse and rode away. (49)

Tostig said they should retreat back to his boats. Hardrada rejected this as being unworthy of a Viking warrior. Aware he was outnumbered he sent a message to his men with his fleet at Ricall to come as soon as possible. He gave orders that his men should stop Harold's army from taking the bridge. "It is said that one particular giant of a man held the bridge single-handed, felling all his attackers with swings from his battleaxe. He was only defeated when he was stabbed from below by a man who was floated down the river under the bridge with a spear." (50)

Once Harold's men had crossed the bridge they engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat with swords and axes. The Norsemen were soon being "cut down in their hundreds". The shield-wall was breached and Hardrada was killed by an arrow in the windpipe. His men hesitated about what to do next. Tostig stepped forward and urged them to continue fighting. Tostig was also killed and the rest were forced into the River Derwent, where large numbers drowned. (51)

Harold and his men were left in possession of the battlefield for only a matter of minutes before the rest of the Viking army, fully armed and armoured, appeared on the scene. The Norwegians immediately delivered a ferocious charge which nearly succeeded in breaking the English, but Harold's army stood firm and by the end of the day, those Vikings still alive, under cover of darkness, retreated. Harold chased them back to Riccall. The twenty-year-old Olaf Haraldsson, now in command of the Norwegians, asked for a peace settlement. Harold agreed and allowed the Vikings to return home. The Norwegian losses were considerable. Of the 300 ships that arrived, less than 25 returned to Norway. Despite the victory, Harold had suffered heavy casualties and his army was severely depleted. However, the battle had shown Harold was a general of great talent. (52)

Battle of Hastings

On 27th September, 1066, the wind in the Channel suddenly changed and William ordered his fleet to set sail. William's ship, The Mora, led the way. A large and fast ship, it carried ten knights and their equipment. Ordericus Vitalis claims that the ship: "it had for its figurehead the image of a child, gilt, pointing with its right hand towards England, and having in its mouth a trumpet of ivory". (53)

William's ship had a lantern slung from its mast head for the others to follow. However, the rest of his heavily laden ships, soon fell far behind and William found himself all alone in mid-Channel. He had to wait until first light before the rest of the fleet caught up. They made landfall at around 9.00 that morning at Pevensey Bay but they had to wait a further two hours for the tide before they could start to disembark. (54)

As the authors of The Battle of Hastings: The Uncomfortable Truth have pointed out: "The Norman ships, given as 696 but certainly many hundreds, could never had arrived at Pevensey at one go and one account states that the disembarkation took place at intervals along the shore. We know that some ships grounded at Romney, far to the east, so that such a large fleet must inevitably have been scattered along the coast. Nevertheless, to have transported such a large force of cavalry across the Channel was a magnificent, in fact unprecedented, achievement and just two vessels were lost on the voyage - one of which carried William's soothsayer who failed to foresee his own demise." (55)

While celebrating his victory at a banquet in York, Harold heard that William had landed at Pevensey Bay. Harold's brother, Gyrth, offered to lead the army against William, pointing out that as king he should not risk the chance of being killed. "I have taken no oath and owe nothing to Count William". (56) David Armine Howarth, the author of 1066: the Year of the Conquest (1981) argues that the suggestion was that while Gyrth did battle with William, "Harold should empty the whole of the countryside behind him, block the roads, burn the villages and destroy the food. So, even if Gyrth was beaten, William's army would starve in the wasted countryside as winter closed in and would be forced either to move upon London, where the rest of the English forces would be waiting, or return to their ships." (57)

Harold rejected the advice and immediately assembled the housecarls who had survived the fighting against King Harald Hardrada and marched south. Harold travelled at such a pace that many of his troops failed to keep up with him. When Harold arrived in London he waited for the local fyrd to assemble and for the troops of the earls of Mercia and Northumbria to arrive from the north. After five days they had not arrived and so Harold decided to head for the south coast without his northern troops. (58)

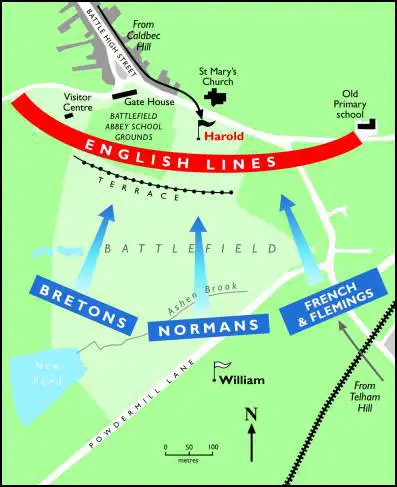

King Harold II realised he was unable to take William by surprise, and so he positioned himself at Senlac Hill near Hastings. Harold selected a spot that was protected on each flank by marshy land. At his rear was a forest. The English housecarls provided a shield wall at the front of Harold's army. They carried large battle-axes and were considered to be the toughest fighters in Europe. The fyrd were placed behind the housecarls. The leaders of the fyrd, the thanes, had swords and javelins but the rest of the men were inexperienced fighters and carried weapons such as iron-studded clubs, scythes, reaping hooks and hay forks.

William of Malmesbury reported: "The courageous leaders mutually prepared for battle, each according to his national custom. The English, as we have heard, passed the night without sleep in drinking and singing, and, in the morning, proceeded without delay towards the enemy; all were on foot, armed with battle-axes... The king himself on foot stood with his brother, near the standard, in order that, while all shared equal danger none might think of retreating... On the other side, the Normans passed the whole night in confessing their sins, and received the Sacrament in the morning. The infantry with bows and arrows, formed the vanguard, while the cavalry, divided into wings, were held back." (59)

There are no accurate figures of the number of soldiers who took part at the Battle of Hastings. Historians have estimated that William had about 5,000 infantry and 3,000 knights while Harold had about 2,000 housecarls and 5,000 members of the fyrd. (60) The Norman historian, William of Poitiers, claims that Harold held the advantage: "The English were greatly helped by the advantage of the high ground... also by their great number, and further, by their weapons which could easily find a way through shields and other defences." (61)

At 9.00 a.m. the Battle of Hastings formally opened with the playing of trumpets. Norman archers then walked up the hill and when they were about a 100 yards away from Harold's army they fired their first batch of arrows. Using their shields, the housecarls were able to block most of this attack. Volley followed volley but the shield wall remained unbroken. At around 10.30 hours, William ordered his archers to retreat.

The Norman army led by William now marched forward in three main groups. On the left were the Breton auxiliaries. On the right were a more miscellaneous body that included men from Poitou, Burgundy, Brittany and Flanders. In the centre was the main Norman contingent "with Duke William himself, relics round his neck, and the papal banner above his head". (62)

The English held firm and eventually the Normans were forced to retreat. Members of the fyrd on the right broke ranks and chased after them. A rumour went round that William was amongst the Norman casualties. Afraid of what this story would do to Norman morale, William pushed back his helmet and rode amongst his troops, shouting that he was still alive. He then ordered his cavalry to attack the English who had left their positions on Senlac Hill. English losses were heavy and very few managed to return to the line. (63)

At about 12.00 p.m. there was a break in the fighting for an hour. This gave both sides a chance to remove the dead and wounded from the battlefield. William, who had originally planned to use his cavalry when the English retreated, decided to change his tactics. At about one in the afternoon he ordered his archers forward. This time he told them to fire higher in the air. The change of direction of the arrows caught the English by surprise. The arrow attack was immediately followed by a cavalry charge. Casualties on both sides were heavy. Those killed included Harold's two brothers, Gyrth and Leofwin. However, the English line held and the Normans were eventually forced to retreat. The fyrd, this time on the left side, chased the Normans down the hill. William ordered his knights to turn and attack the men who had left the line. Once again the English suffered heavy casualties.

William ordered his troops to take another rest. The Normans had lost a quarter of their cavalry. Many horses had been killed and the ones left alive were exhausted. William decided that the knights should dismount and attack on foot. This time all the Normans went into battle together. The archers fired their arrows and at the same time the knights and infantry charged up the hill.

It was now 4.00 p.m. Heavy English casualties from previous attacks meant that the front line was shorter. The Normans could now attack from the side. The few housecarls that were left were forced to form a small circle round the English standard. The Normans attacked again and this time they broke through the shield wall and Harold and most of his housecarls were killed. With their king dead, the fyrd saw no reason to stay and fight, and retreated to the woods behind. The Normans chased the fyrd into the woods but suffered further casualties themselves when they were ambushed by the English.

According to William of Poitiers: "Victory won, the duke returned to the field of battle. He was met with a scene of carnage which he could not regard without pity in spite of the wickedness of the victims. Far and wide the ground was covered with the flower of English nobility and youth. Harold's two brothers were found lying beside him." The next day Harold's mother, Gytha, sent a message to William offering him the weight of the king's body in gold if he would allow her to bury it. He refused, declaring that Harold should be buried on the shore of the land which he sought to guard. (64)

William the Conqueror and Feudalism

William and his army now marched on Dover where he remained for a week. He then went north calling in on Canterbury before arriving on the outskirts of London. He met resistance in Southwark and in an act of revenge set fire to the area. Londoners refused to submit to William so he turned away and marched through Surrey, Hampshire and Berkshire. He ravaged the countryside and by the end of the year the people of London, surrounded by devastated lands, began to consider the possibility of surrender. (65)

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a group of senior figures, including Earl Eadwine of Mercia, Earl Morcar of Northumbria, Edgar Etheling, Ealdred, Archbishop of York and "all the best men from London, who submitted from force of circumstances... They gave him hostages and swore oaths of fealty, and he promised to be a gracious lord to them." On 25th December, 1066, William was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey. (66)

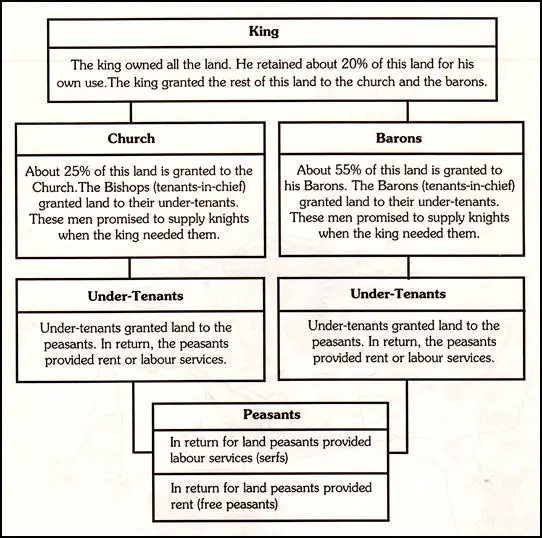

After his coronation, William the Conqueror claimed that all the land in England now belonged to him. William retained about a fifth of this land for his own use. Another 25% went to the Church. The rest were given to 170 tenants-in-chief (or barons), who had helped him defeat Harold at the Battle of Hastings. These barons had to provide armed men on horseback for military service. The number of knights a baron had to provide depended on the amount of land he had been given.

When William granted land to a baron an important ceremony took place. The baron knelt before the king and said: "I become your man." He then placed his hand on the Bible and promised to remain faithful for the rest of his life. The baron would then carry out similar ceremonies with his knights. By the time William and his barons had finished distributing land there were about 6,000 manors in England. Manors varied in size, some having only one village, while others had several villages within its territory. (67)

Richard FitzGilbert is an example of someone who did very well out of the Norman invasion. Richard had the same mother as William the Conqueror, Herleva of Falaise. His father, Gilbert, Count of Brionne, one of the most powerful landowners in Normandy. As Herleva was not married to Gilbert, the boy became known as Richard FitzGilbert. The term 'Fitz' was used to show that Richard was the illegitimate son of Gilbert. (68)

When Robert, Duke of Normandy, William's father died in 1035, William the Conqueror, inherited his father's title. Several leading Normans, including Gilbert of Brionne, Osbern the Seneschal and Alan of Brittany, became William's guardians. A number of Norman barons would not accept an illegitimate son as their leader and in 1040 an attempt was made to kill William. The plot failed but they did manage to kill Gilbert of Brionne. As Richard was illegitimate, he did not receive very much land when his father died. (69)

When William the Conqueror, decided to invade England in 1066, he invited his three half-brothers, Richard FitzGilbert, Odo of Bayeux and Robert of Mortain to join him. Richard, who had married Rohese, daughter of Walter Gifford of Normandy, also brought with him members of his wife's family.

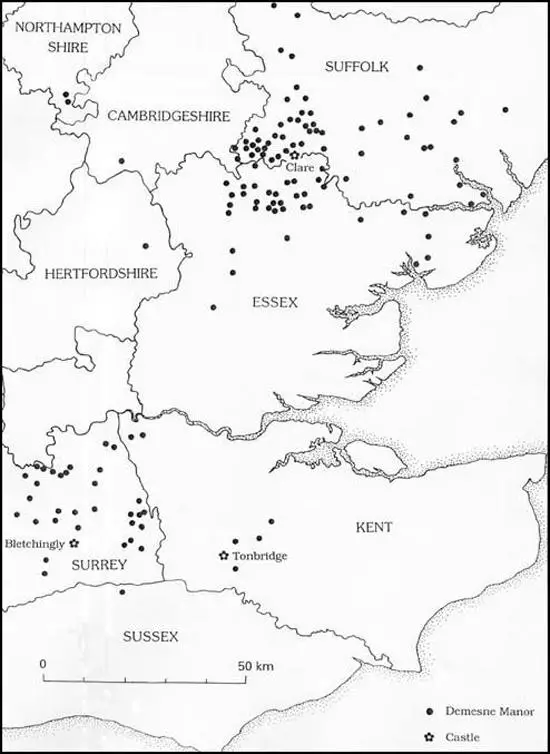

Richard FitzGilbert, was granted land in Kent, Essex, Surrey, Suffolk and Norfolk. In exchange for this land. Richard had to promise to provide the king with sixty knights. In order to supply these knights, barons divided their land up into smaller units called manors. These manors were then passed on to men who promised to serve as knights when the king needed them. (70)

Richard FitzGilbert was given the title, the Earl of Clare. The baron often lived in a castle at the centre of his estates. FitzGilbert built castles at Tonbridge (Kent), Clare (Suffolk), Bletchingley (Surrey) and Hanley (Worcester). His knights normally lived in the manor that they had been granted. Once or twice a year, FitzGilbert would visit his knights to check the manor accounts and to collect the profits that the land had made. (71)

Barons often kept about a third of the land in the manor for their own use (the demesne). Another large area was given to the knight who looked after the manor. The rest was divided up between the church (the glebe land) and the peasants who lived in the village. Those peasants who were freeman would rent the land for an agreed fee. However, the vast majority of the peasants were unfree. These unfree peasants, who were called villeins or serfs, had to provide a whole range of services in exchange for the land that they used. The main requirement of the serf was to supply labour service. This involved working on the demesne without pay for several days a week. As well as free labour, serfs also had to provide the oxen plough-team or any equipment that was needed.

Castle Building

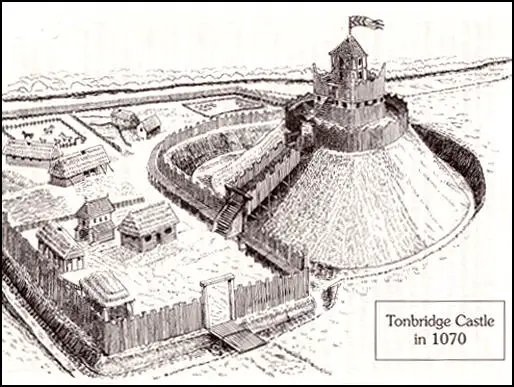

The Normans built their first castle at Hastings soon after they arrived in 1066. They looked for sites that provided natural obstacles to an enemy, such as a steep hill or a large expanse of water. It was also be important to have good views of the surrounding countryside.

The Norman conquerors realised that with only 10,000 soldiers in England, they would be at a disadvantage if the one and a half million Anglo-Saxons decided to rebel against them. To defend the territory they had conquered, the Normans began building castles all over England. It is estimated they built 50 castles in the first 20 years after the invasion. (72)

Richard Fitz Gilbert, like the other Norman leaders, looked for sites that provided natural defences such as a steep hill or a large expanse of water. To protect his estates in Kent, Richard built a castle at Tonbridge, by the side of the River Medway. The castle, built in the motte-and-bailey style, was made of wood. Local peasants were forced to dig a deep circular ditch. The displaced earth was then thrown into the centre to create a high mound called a 'motte'. By the time they finished, the motte was 18 metres (60 feet) high. Richard's labourers erected a wooden tower on top of the mound. The tower provided accommodation and a look-out point.

A courtyard, known as the bailey, was built next to the mound. The bailey was linked to the mound by a bridge. If an attacking force managed to get inside the bailey, the bridge could be pulled up to keep the invaders away from the people in the tower. The bailey was enclosed by a fence of wooden stakes called a palisade. The enclosed area would provide a site for houses and stables. Richard's labourers also built a bridge across the ditch that surrounded the castle. When filled with water, this ditch became known as a moat. The River Medway provided a constant supply of water for the moat at Tonbridge. (73)

William built castles at major centres all over the country. The first ones were built by local people. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle complained that the peasants were "sorely burdened the unhappy people of the country with forced labour on the castles... and when the castles were made they filled them with devils and wicked men." (74)

These castles were later rebuilt in stone. As Trevor Rowley has pointed out: "To many Englishmen the physical impact of the Conquest was manifested in the great feats of construction - the churches and the cathedrals, and, most of all, the castles. It was the latter which provided tangible and irrefutable evidence of Norman political and military domination." (75)

Resistance and Rebellion

In March 1067 William returned to Normandy. As a precaution, he took as hostages, Prince Edgar Etheling, Eadwine, Earl of Mercia, Morcar, Earl of Northumbria, Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury and Harold's brother, Wulfnoth Godwinson. William evidently hoped that he had removed all the English leaders who might have led revolts against the Norman government. (76)

While he was away, several disturbances broke out. The first revolt took place in Wales was directed by Eric the Wild and the rebels failed in their attempts to capture the newly-built Norman castle at Hereford. This was followed by a more serious rebellion in Kent that was led by Count Eustace of Boulogne who was dissatisfied by the land that had been granted to him by William. After Eustace's failure to capture Dover Castle he escaped back to his territory in Europe. (77)

William returned in December 1067 and led his army into Devon and Cornwall. He laid siege to Exeter and after eighteen days the residents surrendered. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that "he made favourable promises to the citizens which were badly kept". (78) William ordered a castle to be built in the town and left behind a garrison to guard against further unrest. (79)

Further rebellions took place in 1069. In January, Robert de Comines, the new Earl of Northumbria, was burned to death in the bishop's palace in Durham. This was followed by a rebellion in York. William had little trouble dealing with the insurrection and after severely punishing the rebels he built a castle in the town. (80)

William also had to deal with raids on the north led by King Sweyn of Denmark. In September 1069, Sweyn's fleet sailed into the Humber. William's army forced the Danes to retreat and then crushed another uprising in Staffordshire. He then burnt crops, house and property of people living between York and Durham. The chroniclers claim that the area was turned into a desert and people died of starvation. The revolt finally came to an end when William's troops captured Chester in 1070. A. L. Morton argues that "the greater part of Yorkshire and Durham was laid waste and remained almost unpeopled for a generation". (81)

In 1071 another revolt broke out. Led by Hereward the rebels captured the Isle of Ely. He held out in the fen country for more than a year. During this period Earl Eadwine of Mercia and Earl Morcar of Northumbria, were killed. William personally led the Norman army against Hereward. He managed to escape but William punished the rebels he caught with mutilation and lifelong imprisonment and built a new castle at Ely. (82)

William returned to Normandy in 1073 and later that year conquered Maine. While he was away Waltheof, the Earl of Northumbria, began to conspire against him. Geoffrey of Coutances led the fight against the uprising and afterwards ordered that all rebels should have their right foot cut off. Waltheof was arrested: "His motives, even his actions, were uncertain at the time and have been contentious ever since. Waltheof certainly did not rebel openly. It may have been simply (as one later version had it) that he knew about a conspiracy against the king and was slow in reporting it, or (following another account) that he went along with the plot when it was first put to him, only to have immediate reservations and throw himself on the king's mercy." William had him executed - the only time capital punishment was inflicted on an English leader during his reign. (83)

Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose, was William's eldest son. Unlike his father, he was a short man and this gave him his nickname 'Curthose' (short boots). He was described by Ordericus Vitalis as "talkative and prodigal, very bold and valiant" with a loud voice and a fluent tongue". (84)

Robert, who was now in his early twenties, fought with his father to defeat his enemies in 1073. Robert suggested that William should return to England and he should be allowed to rule Normandy. William, now in his fifties, refused with the words: "Normandy is mine by hereditary descent and I will never while I live relinquish the government". Robert was unwilling to accept this decision and joined forces with discontented elements in Brittany, Maine and Anjou. (85)

Robert gained support from Roger of Clare, the son of Richard FitzGilbert and he made his base at Gerberoy. William and his army attacked Robert in December 1078. During the battle William was wounded in the arm and was forced to flee the battlefield. William of Malmesbury claims that it was the greatest humiliation suffered by William in his whole military career. (86)

William returned to Rouen and was forced to enter into negotiations with his opponents: "An influential group of senior members of the Norman aristocracy including Roger of Montgomery, Hugh of Granmesnil, and the veteran Roger of Beaumont at once strove to effect a pacification in the interests of Robert and his young associates, many of whom were the sons or younger brothers of the negotiating magnates." (87)

William agreed to withdraw but in 1080 he made another attempt to regain his kingdom. According to one source, another battle was prevented by the Church: "While the two armies were in face of each other, drawn out for battle, and many hearts quailed at the fearful death, and still more fearful fate after death which awaits the reprobate, a cardinal priest of the Roman Church and some pious monks, intervened by divine inspiration, and remonstrated with the chiefs of both armies." (88)

It is claimed that William's wife, Matilda of Flanders, intervened in the dispute and the two men were reconciled. The two men took part in an invasion of Scotland. On his way back Robert established a new Norman fortification at Newcastle, and he remained in England until at least the early months of 1081. (89)

Odo of Bayeux had been left in control of England while William was in Normandy. In 1082 William heard complaints about Odo's behaviour. He returned to England and Odo was arrested and charged with misgovernment and oppression. It was also claimed that Odo was preparing an expedition to Rome to become pope after Gregory VII. Found guilty he was kept in prison for the next five years. (90)

The Domesday Book

In 1085 William returned to England to deal with a suspected invasion by King Canute IV of Denmark. While waiting for the attack to take place he decided to order a comprehensive survey of his kingdom. There were three main reasons why William decided to order a survey. (1) The information would help William discover how much the people of England could afford to pay in tax. (2) The information about the distribution of the population would help William plan the defence of England against possible invaders. (3) There was a great deal of doubt about who owned some of the land in England. William planned to use this information to help him make the right judgements when people were in dispute over land ownership. (91)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles reported: "The king sent his men over all England into every shire and had them find out how many hundred hides there were in the shire, or what land and cattle the king himself had in the country, or what dues he ought to have annually from the shire. Also, he had a record made of how much land his archbishops had, and his bishops and his abbots and his earls - and though I relate it at too great length - what or how much everybody had who was occupying land in England, in land and cattle, and how much money it was worth." (92)

William sent out his officials to every town, village and hamlet in England. They asked questions about the ownership of land, animals and farm equipment and also about the value of the land and how it was used. When the information was collected it was sent to Winchester where it was recorded in a book. About a hundred years after it was produced the book became known as the Domesday Book. Domesday means "day of judgement". It provided an important source of information for historians. John F. Harrison has pointed out that "from this unique document we have an unparalleled picture of early medieval society in England, including much about the peasantry." (93)

William's survey was completed in only seven months. The kingdom was divided into seven circuits and commissioners summoned to each county court landholders and manorial tenants. On the basis of information already known or collected at the sittings of the courts, the objective was to record not only what land and other property, such as animals and ploughs, but who owned them and what they were worth in the reign of Edward the Confessor. (94)

David C. Douglas, the author of William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England (1992), has argued: "Whatever may have been the exact process by which Domesday Book was compiled, it remains an astonishing product of the Conqueror's administration, reflecting at once the problems with which he was faced, and the character of his rule. It was imperative that he should know the resources of his kingdom, for his need of money was always pressing, and never more so than in 1085. He sought therefore to ascertain the taxable capacity of his kingdom, and to see whether more could be exacted from it.... In Domesday Book there is in fact sure testimony of the manner in which William took over (as has been seen) the taxation system of the Old English state, and used it to his own advantage. It is small wonder, therefore, that this was the aspect of the matter which most impressed - and distressed - contemporary observers." (95)

When William the Conqueror knew who the main landowners were, he arranged a meeting for them at Salisbury. At this meeting on 1st August, 1086, he made them all swear a new oath that they would always obey their king. Florence of Worcester claims that the people were very unhappy about the survey as they feared the imposition of higher taxes and "as a consequence the land was vexed with much violence". (96)

In later life William became very fat. In 1087 William was told that King Philip I of France had described him as looking like a pregnant woman. William was furious and on mounted an attack on the king's territory. On 15th August he captured Mantes and set fire to the town. Soon afterwards he fell from his horse and suffered internal injuries. Ordericus Vitalis said that as he was "very corpulent" he "fell sick from the excessive heat and his great fatigues". (97)

William was taken to the priory of St. Gervase. Close to death, he directed that Robert Curthose should succeed him in Normandy and William Rufus should become king of England. William said on his deathbed that "I tremble when I reflect on the grievous sins which burden my conscience, and now, about to be summoned before the awful tribunal of God, I know not what I ought to do. I was too fond of war... I was bred to arms from my childhood, and I am stained with the rivers of blood that I have shed." (98)

William the Conqueror died on 9th September, 1087. His body was taken to Caen to be buried. According to David C. Douglas, the author of William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England (1992), the "attendants actually broke the unwieldy body when trying to force it into the stone coffin, and such an intolerable stench filled the force it into the stone coffin, and such an intolerable stench filled the church that the priests were forced to hurry the service to a close." (99)

Primary Sources

(1) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Version E, entry for 1087.

King William and the chief men loved gold and silver and did not care how sinfully it was obtained provided it came to them. He (William) did not care at all how wrongfully his men got possession of land nor how many illegal acts they did.

(2) In his book Ecclesiastical History, the monk, Ordericus Vitalis described what happened after an English rebellion in the winter of 1069. (c. 1142)

In his anger William ordered that all crops and herds... and food of every kind should be brought together and burned to ashes, so that the whole region north of Humber might be stripped of all means of survival.

(3) William of Jumieges, Deeds of the Dukes of the Normans (c. 1070)

William, Duke of Normandy, never allowed himself to be deterred from any enterprise because of the labour it entailed. He was strong in body and tall in stature. He was moderate in drinking, for he deplored drunkenness in all men. In speech he was fluent and persuasive, being skilled at all times in making clear his will. He followed the Christian discipline in which he had been brought up from childhood, and whenever his health permitted he regularly attended Christian worship each morning and at the celebration of mass.

(4) William of Poitiers, The Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans (c. 1071)

Duke William excelled both in bravery and soldier-craft. He dominated battles, checking his own men in flight, strengthening their spirit, and sharing their dangers.

William was a noble general, inspiring courage, sharing danger, more often commanding men to follow than urging them on from the rear. The enemy (at the Battle of Hastings) lost heart at the mere sight of this marvellous and terrible knight. Three horses were killed under him. Three times he leapt to his feet. Shields, helmets, hauberks were cut by his furious and flashing blade, while yet other attackers were clouted by his own shield.

(5) Pope Gregory VII made the following comments about William the Conqueror in a letter to a friend. (1081)

The king of England, though in certain respects he is not as religious as we would wish, still shows himself to be more acceptable than other kings... he neither destroys nor sells the churches of God.. and he bound priests by oath to dismiss their wives.

(6) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Version E, entry for 1083.

He (William) made large forests for the deer, and passed laws, so that whoever killed a hart or a hind should be blinded. The rich complained and the poor murmured, but the king was so strong that he took no notice of them.

(7) William the Conqueror, confession on his on his deathbed (September, 1087)

I tremble my friends/ when I reflect on the grievous sins which burden my conscience, and now, about to be summoned before the awful tribunal of God, I know not what I ought to do. I was bred to arms from my childhood, and am stained from the rivers of blood I have shed... It is out of my power to count all the injuries which I have caused during the sixty-four years of my troubled life.

(8) David Bates, William the Conqueror : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Tutors named Ralph the Monk and William appear in charters which date from the late 1030s and early 1040s. Their presence, along with later indirect evidence, such as the poetry and histories written to celebrate the conquest of England, suggest that the young William received some sort of literary education, but specific detail is entirely lacking. The main contemporary narrative sources for William's career from the Norman side are the histories written by William of Jumièges and William of Poitiers and, from the English, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. All present problems of interpretation. Jumièges, who initially finished writing in the late 1050s, subsequently resuming work after 1066 and finishing in 1070 or 1071, wrote to glorify the history of Normandy's rulers. Poitiers, whose history was finished before 1077, wrote specifically to praise and justify William's career and the conquest of England. The chronicle, though annalistic and factual, has something of the character of a lament for the English defeat. The two most important historians of the first half of the twelfth century, Orderic Vitalis and William of Malmesbury, also have their own angles on events; both were of Anglo-French parentage, with the former seeing the conquest as a moral problem to be analysed and the latter aiming to set events in the longer-term course of England's history.

Student Activities

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)