Wulfnoth Godwinson

Wulfnoth Godwinson, the son of Earl Godwin, and his wife, Gytha, was probably born in about 1037. There is some evidence to suggest that Godwin was the son of the late tenth-century renegade and pirate Wulfnoth Cild of Compton, West Sussex, who had rebelled against Ethelred the Unready. (1)

Wulfnoth's father Godwin was a strong supporter of King Cnut the Great, and in 1018 he was given the title of Earl of Wessex. Cnut commented that he found Godwin "the most cautious in counsel and the most active in war". He took him to Denmark, where he "tested more closely his wisdom", and "admitted him to his council". Cnut introduced him to Gytha. Her brother Ulf, was married to Cnut's sister. (2)

Godwin had married Gytha, in about 1020. She gave birth to Wulfnoth, Swein, Harold, Tostig, Gyrth and Leofwine and three daughters: Edith, Gunhild and Elfgifu. (3)

Leofwine and Edward the Confessor

During Wulfnoth's childhood his father held an important positioned, helping, along with Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, to govern England during the king's extended absences. In 1042, Godwin helped to arrange for Edward the Confessor, the seventh son of Ethelred the Unready, to become king. (4)

In 1045, Godwin's 20-year-old daughter, Edith, married 42-year-old Edward. Godwin hoped that his daughter would have a son but Edward had taken a vow of celibacy and it soon became clear that the couple would not produce an heir to the throne.

William of Normandy

Edward the Confessor became concerned about the growth in power of Earl Godwin and his sons. According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward promised William of Normandy that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. (5)

Wulfnoth and Hakon, son of Swein, were held as a hostage as assurance of Godwin's good behaviour. Tostig moved to mainland Europe and married Judith of Flanders in the autumn of 1051. (6) Leofwine and Harold went to seek help in Ireland. Earl Godwin, and Swein went to live in Bruges. (7)

Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Queen Edith was removed from court. Jumièges urged Edward to divorce Edith, but he refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery. (8) Edward also appointed other Normans to official positions. This caused great resentment amongst the English and many of them crossed the Channel to offer Godwin their support. (9)

Death of Earl Godwin

Earl Godwin and his sons were furious by these developments and in 1052 they returned to England with a mercenary army. Edward was unable to raise significant forces to stop the invasion. Most of the men in Kent, Surrey and Sussex joined the rebellion. Godwin's large fleet moved round the coast and recruited men in Hastings, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich. He then sailed up the Thames and soon gained the support of Londoners. (10)

Robert of Jumièges fled from the country, taking with him, Wulfnoth and Hakon as prisoners. The two young men were handed over to William of Normandy, who held them in captivity as hostages. William decided to use these men to negotiate his way to the throne. (11)

Negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester. Robert left England and was declared an outlaw. Pope Leo IX condemned the appointment of Stigand as the new Archbishop of Canterbury but it was now clear that the Godwin family was back in control. At a meeting of the King's Council, Godwin cleared himself of the accusations brought against him, and Edward restored him and his sons to land and office, and received Edith once more as his queen. (12)

Godwin now forced Edward the Confessor to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. Earl Godwin died on 15th April, 1053. Some accounts say he choked on a piece of bread. Others say he was accused of being disloyal to Edward and died during an Ordeal by Cake. Another possibility is that he died from a stroke. His place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his eldest son, Harold. (13)

In 1064 Harold of Wessex was on board a ship that was wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and imprisoned at Beaurain. William of Normandy, demanded that Count Guy release him into his care. Guy agreed and Harold went with William to Rouen. William later explained what happened: "Edward sent Harold himself to Normandy so that he could swear to me in my presence what his father, Earl Godwin and Earl Leofric (Mercia) and Earl Siward (Northumbria) had sword to me here in my absence. On the journey Harold incurred the danger of being taken prisoner, from which, using force and diplomacy, I rescued him. Through his own hands he made himself my vassal and with his own hand he gave me a firm pledge concerning the kingdom of England." (14)

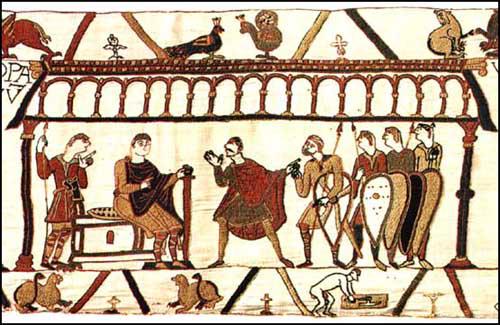

Godwinson (with mustache) in 1064 Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1090)

Harold also negotiated with William about the release of Wulfnoth and Hakon. He did agree to let Hakon go but insisted on holding on to Harold's younger brother until William had become king. Harold's assumption of the crown broke this alleged agreement and Wulfnoth was not released until just before William the Conqueror died in 1087. He was only freed briefly, before William Rufus took him back into captivity. (15)

Wulfnoth Godwinson died in prison in Winchester in 1094.

Primary Sources

(1) John Grehan and Martin Mace, The Battle of Hastings: The Uncomfortable Truth (2012)

Eadmer states that Harold went on his own volition (and indeed against the advice of Edward, who told him that William was not to be trusted), to try and recover his brother and nephew who had been given to William as hostages. As it transpired Harold was able to take his nephew Hakon back to England but not his brother Wulfnoth. The latter would be released when William succeeded to the throne.

Student Activities

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)