King William II (William Rufus)

William Rufus (the Red), the second surviving son of William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders, was born in about 1056. His mother gave birth to nine children. Seven of these survived: William, Robert Curthose, Richard (killed in a hunting accident in about 1074), Cecily, Agatha, Henry Beauclerk and Adela. (1)

As a child he was educated by Lanfranc of Pavia, who was the abbot of Caen. According to Frank Barlow: "If, however, his parents had intended him for the church, the death of their second son, Richard... brought him back to the Conqueror's side to serve as a knight bachelor. An intimate acquaintance with the monastic life at an impressionable age could, however, have inspired in him the ribaldry and contempt for the church he was to display when king." (2)

When he was a young man he obtained the name Rufus because of his ruddy complexion. "William Rufus had a red face, yellow hair, different coloured eyes... astonishing strength, though not very tall and his belly rather projecting... he had a stutter, especially when angry." (3)

William Rufus in Normandy

William the Conqueror had successfully invaded England in 1066. He also controlled Normandy and in 1073, along with his eldest son, Robert Curthose, conquered Maine. Robert, who was now in his early twenties, suggested that William should return to England and he should be allowed to rule Normandy. William, now in his fifties, refused with the words: "Normandy is mine by hereditary descent and I will never while I live relinquish the government". Robert was unwilling to accept this decision and joined forces with discontented elements in Brittany, Maine and Anjou. (4)

Robert gained support from Roger of Clare, the son of Richard FitzGilbert and he made his base at Gerberoy. Although he was only 17 years-old, William Rufus joined his father in battle against his brother. (5) William the Conqueror's army attacked Robert in December 1078. During the battle William was wounded in the arm and was forced to flee the battlefield. William of Malmesbury claims that it was the greatest humiliation suffered by William in his whole military career. (6)

William returned to Rouen and was forced to enter into negotiations with his opponents: "An influential group of senior members of the Norman aristocracy including Roger of Montgomery, Hugh of Granmesnil, and the veteran Roger of Beaumont at once strove to effect a pacification in the interests of Robert and his young associates, many of whom were the sons or younger brothers of the negotiating magnates." (7)

William agreed to withdraw but in 1080 he made another attempt to regain his kingdom. According to one source, another battle was prevented by the Church: "While the two armies were in face of each other, drawn out for battle, and many hearts quailed at the fearful death, and still more fearful fate after death which awaits the reprobate, a cardinal priest of the Roman Church and some pious monks, intervened by divine inspiration, and remonstrated with the chiefs of both armies." (8)

It is claimed that William's wife, Matilda of Flanders, intervened in the dispute and the two men were reconciled. Matilda had always been close to Robert and without her husband's knowledge, used to "send her son vast amounts of silver and gold". When the king discovered his wife's generosity, he threatened to blind the Breton messenger Samson used for these missions. (9)

Death of William the Conqueror

In later life William became very fat. King Philip I of France described him as looking like a pregnant woman. While fighting in Normandy he fell from his horse and suffered internal injuries. Ordericus Vitalis said that as he was "very corpulent" he "fell sick from the excessive heat and his great fatigues". (10)

William was taken to the priory of St. Gervase. Close to death, he directed that Robert Curthose should succeed him in Normandy and William Rufus should become king of England. The decision was an acknowledgement that unlike Robert, Rufus had always remained loyal to his father. (11)

William the Conqueror said on his deathbed that "I tremble when I reflect on the grievous sins which burden my conscience, and now, about to be summoned before the awful tribunal of God, I know not what I ought to do. I was too fond of war... I was bred to arms from my childhood, and I am stained with the rivers of blood that I have shed." (12)

William the Conqueror died on 9th September, 1087. William Rufus was crowned by Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, on 26th September. He was not a popular ruler. "Monastic writers, although acknowledging some of William's virtues, looked askance at his morals. By associating him with what they considered effeminate fashions in dress and comportment they hinted at his homosexuality. And since he never married and is not known to have had any bastards this has been generally accepted.... Rufus has also been judged not only irreligious but also atheistical, even heretical. Certainly he shared the soldier's disrespect for Christian morality and the clerical life." (13)

King of England

William Rufus was very unpopular with the Church. Unlike his father, Rufus was not a committed Christian. His father's policy of spending considerable sums of money on the Church was reversed. When Rufus needed to raise money, he raided monasteries. Austin Lane Poole has argued that "from a moral standpoint... probably the worst king that has occupied the throne of England." (14)

It was recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: "He (William Rufus) was very harsh and severe over his land and his men, and with all his neighbours; and very formidable; and through the counsels of evil men, that to him were always agreeable, and through his own avarice, he was ever tiring this nation with an army, and with unjust contributions. For in his days all right fell to the ground, and every wrong rose up before God and before the world. God's church he humbled; and all the bishoprics and abbacies, whose elders fell in his days, he either sold in fee, or held in his own hands, and let for a certain sum; because he would be the heir of every man, both of the clergy and laity." (15)

The division of the Conqueror's lands created political difficulties as most Norman lords held estates on both sides of the Channel. Odo of Bayeux commented: "How can we give proper service to two mutually hostile and distant lords? If we serve Duke Robert well we shall offend his brother William, and he will deprive us of our revenues and honours in England. On the other hand if we obey King William, Duke Robert will deprive us of our patrimonies in Normandy." (16)

In 1088 some Normans, including Odo of Bayeux, Robert of Mortain, Richard Fitz Gilbert, William Fitz Osbern and Geoffrey of Coutances, led a rebellion against the rule of William Rufus in order to place his brother, Robert Curthose on the throne. However most Normans in England remained loyal and Rufus and his army successfully attacked the rebel strongholds at Tonbridge, Pevensey and Rochester. The leaders of the revolt were exiled to Normandy. (17)

In February 1091, Rufus personally led an army into north-eastern Normandy against Robert Curthose. Robert accepted defeat and negotiated a peace on terms highly favourable to Rufus. In essence, their treaty provided for the division of Normandy between them, to the total exclusion and disinheritance of their younger brother, Henry Beauclerk. Rufus and Curthose then marched westward against their brother, forcing Henry to withdraw to the mountain-top abbey of Mont-St Michel. Curthose and Rufus besieged their younger brother until April 1091, with water running short, Henry agreed to relinquish the abbey and departed Normandy. (18)

Robert accompanied Rufus to England in autumn 1091 and soon afterwards marched against King Malcolm III, whose Scots army had invaded the country in his absence. The campaign was a success and Malcolm was forced to submit at the Firth of Forth. He returned to Normandy in December but had difficulty controlling his territory. He renounced the treaty with his brother William, who in February 1094 returned to Normandy and throughout 1094 and 1095 the conflict between the brothers was evenly matched. To pay for the campaign he imposed heavy taxes on the people of England. Some of this money was used to bribe King Philip I of France not to support Robert. Ordericus Vitalis indicates that Rufus controlled more than twenty castles in Normandy. (19)

In 1095 William Rufus decided to bring Robert of Mowbray, the Earl of Northumberland, to justice. He took Newcastle and Tynemouth before besieging Mowbray at Bamborough. William was forced to end this campaign when he heard the Welsh had captured Montgomery. By the time he reached the area the Welsh had abandoned Montgomery and had withdrawn to the mountains. (20)

In 1096 William Rufus imposed a new tax on his barons. When they complained they did not have this money, William Rufus suggested that they should rob the shrines of the saints. Later that year William Rufus seized the property of Anselm, the Archbishop of Canterbury, while he was in Rome. (21)

Rufus now formed a new alliance with his brother Henry and by 1096 Normandy was under his control. Robert joined the First Crusade and was one of those involved in capturing Jerusalem in July 1099. Robert married Sybilla of Conversano, daughter of Geoffrey of Brindisi, Count of Conversano on the way back from Crusade. (22)

Over the next few months William Rufus was involved in military campaigns in Wales, Scotland and Normandy. In January 1098 his forces captured Maine and besieged Le Mans. He also fought a war against King Philip I of France but after facing stubborn resistance he agreed a truce in April 1099. (23)

Death of William Rufus

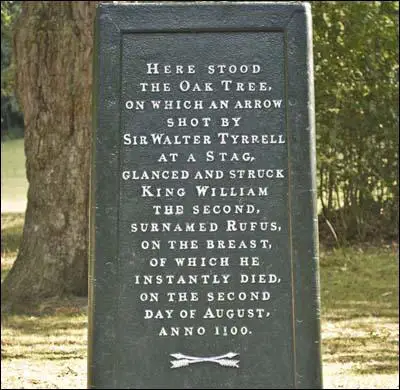

On 2nd August 1100, King William Rufus went hunting at Brockenhurst in the New Forest. Gilbert de Clare and his younger brother, Roger of Clare, were with the king. Another man in the hunting party was Walter Tirel, who was married to Richard de Clare's daughter, Adelize. Also present was William Rufus' younger brother Henry Beauclerk. (24)

William of Malmesbury later described what happened during the hunt: "The sun was now declining, when the king, drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded a stag which passed before him... The stag was still running... The king, followed it a long time with his eyes, holding up his hand to keep off the power of the sun's rays. At this instant Walter decided to kill another stag. Oh, gracious God! the arrow pierced the king's breast. On receiving the wound the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the arrow where it projected from his body... This accelerated his death. Walter immediately ran up, but as he found him senseless, he leapt upon his horse, and escaped with the utmost speed. Indeed there were none to pursue him: some helped his flight; others felt sorry for him." (25)

Tirel escaped to France and never returned again to England. Most people expected Robert Curthose to become king. However, Henry decided to take quick action to gain the throne. As soon as he realised William Rufus was dead, Henry rushed to Winchester where the government's money was kept. After gaining control of the treasury, Henry declared he was the new king. (26)

Supported by Gilbert de Clare and Roger of Clare, Henry was crowned king on 5th August. Although Robert threatened to invade England, he eventually agreed to do a deal with Henry. In return for an annual payment of £2,000, Robert accepted Henry as king of England. (27)

King Henry I generously rewarded the Clare family for their loyalty. Although Walter Tirel never returned to England, his son was allowed to keep his father's estates. Some people suspected that Henry and the Clare family had planned the murder of William Rufus. Others accepted that William Rufus' death was an accident. Whatever the truth of the matter, the Clare family obtained considerable benefit from the death of William Rufus. (28)

Primary Sources

(1) William of Malmesbury, Chronicle of the Kings of the English (c1128)

William Rufus had a red face, yellow hair, different coloured eyes... astonishing strength, though not very tall and his belly rather projecting... he had a stutter, especially when angry.

(2) John Horace Round, Feudal England (1895) page 468

Gilbert and Roger, sons of Richard de Clare, who were present at Brockenhurst when the King was killed... were brothers-in-law of Walter Tirel... Richard, another brother-in-law, was promptly selected to be Abbot of Ely by King Henry I, who further gave the see of Winchester to William Giffard, another member of the same powerful family circle.

(3) Frank Barlow, William Rufus (1983)

Historians... have hinted that barons... perhaps led by the Clares... had arranged William's death. But there is not a shred of good evidence and the theory merely avoids the obvious. Hunting accidents were, after all, not uncommon.

(4) William of Malmesbury, Chronicle of the Kings of the English (c. 1128)

The day before the king died he dreamt that he went to heaven. He suddenly awoke. He commanded a light to be brought, and forbade his attendants to leave him.

The next day he went into the forest... He was attended by a few persons... Walter Tirel remained with him, while the others, were on the chase.

The sun was now declining, when the king, drawing his bow and letting fly an arrow, slightly wounded a stag which passed before him... The stag was still running... The king, followed it a long time with his eyes, holding up his hand to keep off the power of the sun's rays. At this instant Walter decided to kill another stag. Oh, gracious God! the arrow pierced the king's breast.

On receiving the wound the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the arrow where it projected from his body... This accelerated his death. Walter immediately ran up, but as he found him senseless, he leapt upon his horse, and escaped with the utmost speed. Indeed there were none to pursue him: some helped his flight; others felt sorry for him.

The king's body was placed on a cart and conveyed to the cathedral at Winchester... blood dripped from the body all the way. Here he was buried within the tower. The next year, the tower fell down.

William Rufus died in 1100... aged forty years. He was a man much pitied by the clergy... he had a soul which they could not save... He was loved by his soldiers but hated by the people because he caused them to be plundered.

(5) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1100)

A.D. 1100. In this year the King William held his court at Christmas in Glocester, and at Easter in Winchester, and at Pentecost in Westminster. And at Pentecost was seen in Berkshire at a certain town blood to well from the earth; as many said that should see it. And thereafter on the morning after Lammas day was the King William shot in hunting, by an arrow from his own men, and afterwards brought to Winchester, and buried in the cathedral. This was in the thirteenth year after that he assumed the government. He was very harsh and severe over his land and his men, and with all his neighbours; and very formidable; and through the counsels of evil men, that to him were always agreeable, and through his own avarice, he was ever tiring this nation with an army, and with unjust contributions. For in his days all right fell to the ground, and every wrong rose up before God and before the world. God's church he humbled; and all the bishoprics and abbacies, whose elders fell in his days, he either sold in fee, or held in his own hands, and let for a certain sum; because he would be the heir of every man, both of the clergy and laity; so that on the day that he fell he had in his own hand the archbishopric of Canterbury, with the bishopric of Winchester, and that of Salisbury, and eleven abbacies, all let for a sum; and (though I may be tedious) all that was loathsome to God and righteous men, all that was customary in this land in his time. And for this he was loathed by nearly all his people, and odious to God, as his end testified: for he departed in the midst of his unrighteousness, without any power of repentance or recompense for his deeds. On the Thursday he was slain; and in the morning afterwards buried; and after he was buried, the statesmen that were then nigh at hand, chose his brother Henry to king. And he immediately gave the bishopric of Winchester to William Giffard; and afterwards went to London; and on the Sunday following, before the altar at Westminster, he promised God and all the people, to annul all the unrighteous acts that took place in his brother's time, and to maintain the best laws that were valid in any king's day before him. And after this the Bishop of London, Maurice, consecrated him king; and all in this land submitted to him, and swore oaths, and became his men.

Student Activities

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)