Tostig Godwinson

Tostig Godwinson, the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex, and his wife, Gytha, was born in about 1025. (1) There is some evidence to suggest that Godwin was the son of the late tenth-century renegade and pirate Wulfnoth Cild of Compton, West Sussex, who had rebelled against Ethelred the Unready. (2)

Tostig's father Godwin was a strong supporter of King Cnut the Great, and in 1018 he was given the title of Earl of Wessex. Cnut commented that he found Godwin "the most cautious in counsel and the most active in war". He took him to Denmark, where he "tested more closely his wisdom", and "admitted him to his council". Cnut introduced him to Gytha. Her brother Ulf, was married to Cnut's sister. (3)

Godwin had married Gytha, in about 1020. She gave birth to Tostig, Swein, Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth and three daughters: Edith, Gunhild and Elfgifu. (4)

Tostig Godwinson and Edward the Confessor

During Tostig's childhood his father held an important positioned, helping, along with Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, to govern England during the king's extended absences. In 1042, Godwin helped to arrange for Edward the Confessor, the seventh son of Ethelred the Unready, to become king. The following year Godwin's eldest son, Swein, became Earl of the South-West Midlands. (5)

In 1045, Godwin's 20-year-old daughter, Edith, married 42-year-old Edward. Godwin hoped that his daughter would have a son but Edward had taken a vow of celibacy and it soon became clear that the couple would not produce an heir to the throne. Christopher Brooke, the author of The Saxon and Norman Kings (1963), has suggested that this story might have been made up as a part of the legend of royal piety, and as a delicate compliment to a queen who suffered from the common misfortune of failing to bear children." (6)

Edward the Confessor became concerned about the growth in power of Earl Godwin and his sons. According to Norman historians, William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers in April 1051, Edward promised William of Normandy that he would be king of the English after his death. David Bates argues that this explains why Earl Godwin, raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile. (7) Harold and Leofwine went to seek help in Ireland. Earl Godwin, Swein and the rest of the family went to live in Bruges. (8)

Tostig moved to mainland Europe and married Judith of Flanders, in the autumn of 1051. Judith was the eldest daughter of the West Frankish King and later Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Bald and his wife Ermentrude of Orléans, who was first cousin to Edward the Confessor. The marriage contracted was a considerable coup for the Godwin clan. (9)

Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury and Queen Edith was removed from court. Jumièges urged Edward to divorce Edith, but he refused and instead she was sent to a nunnery. (10) Edward also appointed other Normans to official positions. This caused great resentment amongst the English and many of them crossed the Channel to offer Godwin their support. (11)

Godwin and his sons were furious by these developments and in 1052 they returned to England with a mercenary army. Negotiations between the king and the earl were conducted with the help of Stigand, the Bishop of Winchester. Robert left England and was declared an outlaw. Pope Leo IX condemned the appointment of Stigand as the new Archbishop of Canterbury but it was now clear that the Godwin family was back in control. (12)

At a meeting of the King's Council, Godwin cleared himself of the accusations brought against him, and Edward restored him and his sons to land and office, and received Edith once more as his queen. Earl Swein did not return and instead set off from Bruges on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, "to look to the salvation of his soul". John of Worcester says that he walked barefoot all the way and that on the journey home he became ill and died in Lycia on 29th September 1052. (13)

Godwin now forced Edward the Confessor to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. Earl Godwin died on 15th April, 1053. Some accounts say he choked on a piece of bread. Others say he was accused of being disloyal to Edward and died during an Ordeal by Cake. Another possibility is that he died from a stroke. His place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his eldest son, Harold. (14)

Earl of Northumbria

In 1055 Tostig became the Earl of Northumbria. At this time the area was in a lawless state and men were forced to travel in parties of twenty to protect themselves from the attacks of robbers. Tostig imposed new laws and all captured robbers were punished with mutilation or death. This strategy was successful and Northumbria came under his firm control.

It has been claimed that "Tostig was held in special affection by Edward the Confessor and his appointment may have owed much to the combined influence of his elder brother Harold and his sister Queen Edith". His biographer, William M. Aird has pointed out: "Tostig is described as a man of courage, endowed with great wisdom and shrewdness of mind. He was favourably compared with his brother Harold, both being distinctly handsome and graceful, similar in strength and bravery." (15)

It is recorded that Tostig "so reduced the number of robbers and cleared the country of them by mutilating or killing them so that any man... could travel at will even alone without fear of attack". (16) It was argued that "a man of property could travel the country safely, even carrying a purse of gold". However, some chroniclers accused him of using his position to enrich himself. (17)

In 1063 Edward the Confessor ordered Tostig and Harold to invade Wales. Tostig led the cavalry in this successful operation. Tostig's rule became increasingly tyrannical. In 1064 he had a meeting with two important thegns, Gamel and Ulf, who wanted to complain about his heavy taxes. During the meeting Tostig ordered their arrest and execution. Later that year he arranged the murder of a noble named Gospatric.

In 1064 Harold of Wessex was on board a ship that was wrecked on the coast of Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy of Ponthieu and imprisoned at Beaurain. William of Normandy, demanded that Count Guy release him into his care. Guy agreed and Harold went with William to Rouen. William later explained what happened: "Edward sent Harold himself to Normandy so that he could swear to me in my presence what his father, Earl Godwin and Earl Leofric (Mercia) and Earl Siward (Northumbria) had sword to me here in my absence. On the journey Harold incurred the danger of being taken prisoner, from which, using force and diplomacy, I rescued him. Through his own hands he made himself my vassal and with his own hand he gave me a firm pledge concerning the kingdom of England." (18)

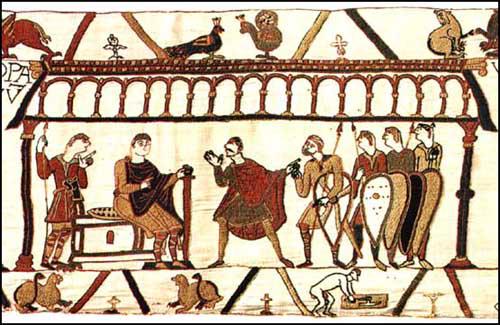

Godwinson (with mustache) in 1064 Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1090)

In 1065 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that Tostig was guilty of robbing churches, depriving men of their lands and lives, and acting against the law. (19) In October a group of rebels, supported by Earl Edwin of Mercia and his brother Morcar, broke into Tostig's residence in York and killed those of his soldiers who did not escape. The rebels then nominated Morcar as their earl. Anyone associated with Tostig's regime was killed. (20)

When the king heard the news he called a meeting of his nobles at Britford. Several made complaints about Tostig's rule claiming that his desire for wealth had made him unduly severe. The king sent Harold to put down the rebellion. Harold disagreed with this policy as he was convinced it would result in a disastrous civil war. At a meeting at Oxford on 28th October, Harold yielded to their demands. Tostig was banished from the country and Morcar, Harold's brother-in-law, became the new Earl of Northumbria. (21)

Stamford Bridge

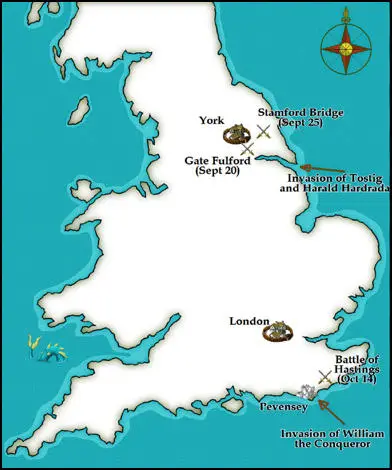

Hardrada then moved onto York, which formally surrendered on 24th September. Hardrada took 150 children hostage from prominent families in Yorkshire as surety for their loyalty. Morcar and Edwin and the remnants of their army escaped into the countryside. The Norwegians now withdrew to Stamford Bridge, a place where several Roman roads met. The bridge would have been quite large by eleventh-century standards. (22)

It has been claimed that a messenger told Harold about the Norwegian victory at Fulford Gate he said that Hardrada had come to conquer all of England. Apparently Harold replied: "I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet." Harold then sent a summons for the men of the fyrd to reassemble, just days after they had been released from their long summer vigil. Having gathered as many of his men as he could he started for the north on about the 19th September. (23)

Harold and his English army marched 190 miles from London to York. The historian, Frank McLynn, the author of 1066: The Year of The Three Battles (1999), has commented "the speed of his advance has always drawn superlatives from historians used to the ponderous pace of medieval warfare, but it may be that a good deal of his force was on horseback and that, as was the custom with Anglo-Saxon armies, they dismounted before fighting." (24)

Peter Rex argues in Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King (2005) that his housecarls were on horseback: "Such mounted infantry could manage twenty-five miles a day. They were also expected to have at least two horses, riding one and allowing the other to proceed unburdened. Harold no doubt could also expect, as king, to commandeer fresh horses along the way. If he did literally ride day and night he could have made Tadcaster in four days, although that would mean without sleep." (25)

On 25th September Harold's army arrived at Stamford Bridge. Harold and twenty of his housecarls rode up to the foot of the bridge on the left bank of the Derwent and had a meeting with Tostig. Harold promised his brother that if he changed sides he would be rewarded with the return of his earldom and one-third of all England. Tostig answered that it would never be said of him that he brought the king of Norway to England only to betray him. He turned on his horse and rode away. (26)

Tostig said they should retreat back to his boats. Hardrada rejected this as being unworthy of a Viking warrior. Aware he was outnumbered he sent a message to his men with his fleet at Ricall to come as soon as possible. He gave orders that his men should stop Harold's army from taking the bridge. "It is said that one particular giant of a man held the bridge single-handed, felling all his attackers with swings from his battleaxe. He was only defeated when he was stabbed from below by a man who was floated down the river under the bridge with a spear." (27)

Once Harold's men had crossed the bridge they engaged the enemy in hand-to-hand combat with swords and axes. The Norsemen were soon being "cut down in their hundreds". The shield-wall was breached and Hardrada was killed by an arrow in the windpipe. His men hesitated about what to do next. Tostig stepped forward and urged them to continue fighting. Tostig was also killed and the rest were forced into the River Derwent, where large numbers drowned. (28)

Harold and his men were left in possession of the battlefield for only a matter of minutes before the rest of the Viking army, fully armed and armoured, appeared on the scene. The Norwegians immediately delivered a ferocious charge which nearly succeeded in breaking the English, but Harold's army stood firm and by the end of the day, those Vikings still alive, under cover of darkness, retreated. Harold chased them back to Riccall. The twenty-year-old Olaf Haraldsson, now in command of the Norwegians, asked for a peace settlement. Harold agreed and allowed the Vikings to return home. The Norwegian losses were considerable. Of the 300 ships that arrived, less than 25 returned to Norway. (29)

Primary Sources

(1) William M. Aird, Tostig of Wessex : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The twelfth-century historian Henry of Huntingdon believed that the rift between Harold and Tostig had occurred shortly after their successful invasion of Wales in 1063. Jealous of his brother's higher place in the king's affections, Tostig went to Hereford, where Harold was preparing a banquet to entertain the king, and had Harold's servants dismembered and served up for the royal guest. Tostig was thus forced into exile along with his wife, Judith, and his lieutenant, Copsi. It may be at this date that the shires of Northampton and Huntingdon were detached from the earldom and granted to Siward's son, Waltheof, who had been denied the earldom of Northumbria in 1055 and now again in 1065. The author of the life of King Edward sees the failure of Edward to reinstate Tostig as marking the beginning of his physical decline. Queen Edith also tried to intervene on her brother's behalf, but in vain. Tostig took leave of his mother and crossed the channel, with his wife and infant children and members of his immediate retinue, after 1 November 1065. According to the life of King Edward the exiles were welcomed by Count Baudouin (V) of Flanders a few days before Christmas and given a house and estate in St Omer, together with the revenues of the town as maintenance. Orderic Vitalis, writing in the early twelfth century, believed that during his exile Earl Tostig had visited Duke William of Normandy in an attempt to forge an alliance against Harold. Similarly Snorri Sturluson's King Harald's Saga, written at the end of the twelfth century, suggests that Tostig had travelled to Denmark and then Norway in order to enlist the aid of kings Swein and Harald in his attack on England. After Tostig's departure, his brother Harold may have formed an alliance with earls Eadwine and Morcar and began to advance his own claims to the English throne. The enmity between the brothers was not ended by Harold's coronation and Tostig was absent from the ceremony.

Shortly after the appearance of Halley's comet on 24 April 1066, Tostig attempted to recover his place by making raids on England. He attacked the Isle of Wight, taking plunder and provisions before moving along the coast to Thanet, where, according to Gaimar, he was met by Copsi. They attacked ‘Brunemue’ before entering the Humber. Driven out of Lindsey by earls Eadwine and Morcar and deserted by his Flemish allies, Tostig made his way to Scotland. He seems to have joined up with King Harald Hardrada of Norway at the mouth of the River Tyne early in September 1066. The two entered the Humber and by way of the Ouse landed at Riccal. On 20 September they defeated the forces of earls Eadwine and Morcar at Gate Fulford but were themselves defeated and killed by King Harold at Stamford Bridge, on the Derwent, on 25 September. Tostig's lieutenant, Copsi, may have been with his master at the battle, but he survived and was later to hold the earldom under William I. After Tostig's death, his widow, Judith, remained in Flanders until late 1070 or early 1071, when she married Welf (IV), duke of Bavaria.

Student Activities

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)