Peter of Blois

Peter of Blois was born in Blois in about 1130. His father was a nobleman who was forced into exile because of "gross immorality". (1) He attended the school attached to the cathedral at Tours in the early 1140s. Here he studied under the great master Bernard Silvestris, who taught literature and the art of writing, particularly letter-writing. (2)

He also studied in Paris and Bologna, where he studied Roman law, under Baldwin of Forde. He than found employment in the Norman court in Sicily. (3) In 1169 he became involved in the negotiations between Archbishop Thomas Becket and Pope Alexander III. This included writing letters for Rotrou, the Archbishop of Rouen. On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see. (4)

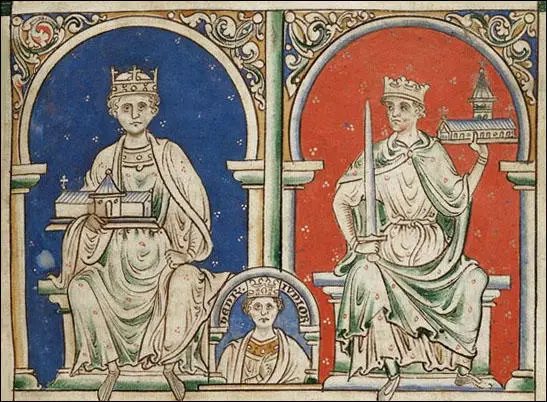

King Henry II was impressed with Peter of Blois and invited him to work for him in England as his secretary. His main task was to write the king's letters. He later reported that Henry was in "constant conversation with the best scholars" and enjoyed discussing "intellectual problems". He added that Henry "does not linger in his palaces like other kings but hunts through the country inquiring into what everyone was doing, especially judges whom he has made judges of others". He was less impressed with his son, Henry the Young, who he accused of being "a leader of freebooters who consorted with outlaws and excommunicates". (5)

In April 1173 he was elected bishop of Bath. He was also employed by Richard of Dover, the Archbishop of Canterbury as his chief letter writer. According to his biographer, Richard W. Southern: "Peter would greatly have preferred to stay in France, but there were many more administrative posts available in England, so he had reluctantly to settle down in a country whose language he never managed to learn." (6)

Peter of Blois became an important source of information on Henry II. He wrote to a friend: "If the king said he will remain in a place for a day.... he is sure to upset all the arrangements by departing early in the morning. And you then see men dashing around as if they were mad... If, on the other hand, the king orders an early start, he is sure to change his mind, and you can take it for granted that he will sleep until midday. Then you will see the packhorses loaded and waiting, the carts prepared, the courtiers dozing, traders fretting, and everyone grumbling... Many a time when the king was sleeping, a message would be passed from his chamber about a city or town he intended to go to... But when our courtiers had gone ahead almost the whole day's ride, the king would turn aside to some other place... I hardly dare say it, but I believe that in truth he took a delight in seeing what a fix he put us in." (7)

Peter of Blois wrote an account of Henry II's reign which he called The Deceptions of Fortune: "When he was writing this work he evidently thought that Henry II was going to triumph over his misfortunes and thus prove the deceptiveness of fortune. As will become evident, this hope was itself to prove deceptive as Henry collapsed under the weight of his misfortunes, and Peter's laudatory work has not survived". (8) However, several of his letters have survived and "are distinguished by their sharp, acerbic wit and observation". (9)

In his letters Peter of Blois provides a vivid portrait of Henry II. He says the king was of medium height, with a strong square chest, and legs slightly bowed from endless days on horseback. His hair was reddish and his head was kept closely shaved. His blue-grey eyes were described as "dove-like" when in a good mood but "gleaming like fire when his temper was aroused", and flashing "like lightning" in bursts of passion. (10)

Henry II sent Peter of Blois on several diplomatic missions and was twice at the papal court, in 1169 and 1179. In 1182, Reginald Fitzjocelin, the Bishop of Bath, made Peter his archdeacon. Soon afterwards he wrote to a friend: "I rejoice with all my heart in our identity of name… Our writings have carried our fame throughout the world so that neither flood nor fire nor any calamity nor the passage of time can obliterate our name". (11)

On 12th December, 1189, left England and took part in the Third Crusade. He asked his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, to help run the country. She agreed and appointed Peter as her chancellor. According to Alison Weir, the author of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1999): "Peter of Bois... was a brilliant writer, his letters are peppered with sharp, acerbic wit and perspicacious observation; Henry II had been impressed by them that he had amassed a collection. Peter was, however, a difficult man to work with, being vain, pedantic and eternally dissatisfied with his position in life, complaining constantly that he never received the preferment his talents deserved. Nevertheless, he stayed with Eleanor for some years and served her well." (12)

Peter of Blois died in about 1211.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter of Blois, The Chronicles of Peter of Blois (c. 1185)

With King Henry II it is school every day, constant conversation with the best scholars and discussions of intellectual problems... He does not linger in his palaces like other kings but hunts through the country inquiring into what everyone was doing, especially judges whom he has made judges of others.

(2) Peter of Blois, a letter to his friend (c. 1185)

If the king said he will remain in a place for a day.... he is sure to upset all the arrangements by departing early in the morning. And you then see men dashing around as if they were mad... If, on the other hand, the king orders an early start, he is sure to change his mind, and you can take it for granted that he will sleep until midday. Then you will see the packhorses loaded and waiting, the carts prepared, the courtiers dozing, traders fretting, and everyone grumbling... Many a time when the king was sleeping, a message would be passed from his chamber about a city or town he intended to go to... But when our courtiers had gone ahead almost the whole day's ride, the king would turn aside to some other place... I hardly dare say it, but I believe that in truth he took a delight in seeing what a fix he put us in.

Student Activities

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

Wandering Minstrels in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)