Protestant Reformation

In 1508 Martin Luther began studying at the newly founded University of Wittenberg. He was awarded his Doctor of Theology on 21st October 1512 and was appointed to the post of professor in biblical studies. He also began to publish theological writings. Luther was considered to be a good teacher. One of his students commented that he was "a man of middle stature, with a voice that combined sharpness in the enunciation of syllables and words, and softness in tone. He spoke neither too quickly nor too slowly, but at an even pace, without hesitation and very clearly." (1)

Luther began to question traditional Catholic teaching. This included the theology of humility (whereby confession of one's own utter sinfulness is all that God asks) and the theology of justification by faith (in which human beings are seen as incapable of any turning towards God by their own efforts). (2)

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar arrived in Wittenberg. He was selling documents called indulgences that pardoned people for the sins they had committed. Tetzel told people that the money raised by the sale of these indulgences would be used to repair St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Luther was very angry that Pope Leo X was raising money in this way. He believed that it was wrong for people to be able to buy forgiveness for sins they had committed. Luther wrote a letter to the Bishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. (3)

Martin Luther & Ninety-five Theses

On 31st October, 1517, Martin Luther affixed to the castle church door, which served as the "black-board" of the university, on which all notices of disputations and high academic functions were displayed, his Ninety-five Theses. The same day he sent a copy of the Theses to the professors of the University of Mainz. They immediately agreed that they were "heretical". (4) For example, Thesis 86, asks: "Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?" (5)

As Hans J. Hillerbrand has pointed out: "By the end of 1518, according to most scholars, Luther had reached a new understanding of the pivotal Christian notion of salvation, or reconciliation with God. Over the centuries the church had conceived the means of salvation in a variety of ways, but common to all of them was the idea that salvation is jointly effected by humans and by God - by humans through marshalling their will to do good works and thereby to please God, and by God through his offer of forgiving grace. Luther broke dramatically with this tradition by asserting that humans can contribute nothing to their salvation: salvation is, fully and completely, a work of divine grace." (6)

Pope Leo X ordered Luther to stop stirring up trouble. This attempt to keep Luther quiet had the opposite effect. Luther now started issuing statements about other issues. For example, at that time people believed that the Pope was infallible (incapable of error). However, Luther was convinced that Leo X was wrong to sell indulgences. Therefore, Luther argued, the Pope could not possibly be infallible.

During the next year Martin Luther wrote a number of tracts criticising the Papal indulgences, the doctrine of Purgatory, and the corruptions of the Church. "He had launched a national movement in Germany, supported by princes and peasants alike, against the Pope, the Church of Rome, and its economic exploitation of the German people." (7)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Johann Tetzel published a response to Luther's tracts. Tetzel's Theses opposed all of Luther's suggested reforms. Henry Ganss has admitted that it was probably a mistake to give Tetzel this task. "It must be admitted that they at times gave an uncompromising, even dogmatic, sanction to mere theological opinions, that were hardly consonant with the most accurate scholarship. At Wittenberg the created wild excitement, and an unfortunate hawker who offered them for sale, was mobbed by the students, and his stock of about eight hundred copies publicly burned in the market square - a proceeding that met with Luther's disapproval." (8)

In 1520 Martin Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation. In the tract he argued that the clergy were unable or unwilling to reform the Church. He suggested the kings and princes must step in and carry out this task. Luther went on to claim that reform is impossible unless the Pope's power in Germany is destroyed. He urged them to bring an end to the rule of clerical celibacy and the selling of indulgences. "The German nation and empire must be freed to live their own lives. The princes must make laws for the moral reform of the people, restraining extravagance in dress or feasts or spices, destroying the public brothels, controlling the bankers and credit." (9)

Humanists like Desiderius Erasmus had criticised the Catholic Church but Luther's attack was very different. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "From the beginning there was a fundamental difference between Erasmus and Luther, between the humanists and the Lutherans. The humanists wished to remove the corruptions and to reform the Church in order to strengthen it; the Lutherans, almost from the beginning, wished to overthrow the Church, believing that it had become incurably wicked and was not the Church of Christ on earth." (10)

On 15th June 1520, the Pope issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against Pope Leo X. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!" (11)

Emperor Charles V & the Reformation

Martin Luther was protected by Frederick III of Saxony. Pressure was placed on Emperor Charles V by the Pope to deal with Luther. Charles responded by claiming: "I am born of the most Christian emperors of the noble German nation, of the Catholic kings of Spain, the archdukes of Austria, the dukes of Burgundy, who were all to the death true sons of the Roman church, defenders of the Catholic faith, of the sacred customs, decrees and usages of its worship... Therefore I am determined to set my kingdoms and dominions, my friends, my body, my blood, my life, my soul upon the unity of the Church and the purity of the faith." (12)

Emperor Charles V was totally opposed to the ideas of Martin Luther and it is reported that when he was presented with a copy of To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation he tore it up in a rage. However, he was in a difficult position. As Derek Wilson has pointed out: "In most of his rag-bag of territories Charles ruled by right of inheritance but in Germany he held the crown by consent of the electors, chief among whom was Frederick of Saxony." (13)

The twenty-year old Emperor Charles invited Martin Luther to meet him in the city of Worms. On 18th April 1521, Charles asked Luther if he was willing to recant. He replied: "Unless I am proved wrong by Scriptures or by evident reason, then I am a prisoner in conscience to the Word of God. I cannot retract and I will not retract. To go against the conscience is neither safe nor right. God help me." (14)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey suggested to Henry VIII that he might want to distinguish himself from other European princess by showing himself to be erudite as well as a supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. With the help of Wolsey and Thomas More, Henry composed a reply to Martin Luther entitled In Defence of the Seven Sacraments. (15) Pope Leo X was delighted with the document and in 1521 he granted him the title, Defender of the Faith. Luther responded by denouncing Henry as the "king of lies" and a "damnable and rotten worm". As Peter Ackroyd has pointed out: "Henry was never warmly disposed towards Lutherism and, in most respects, remained an orthodox Catholic." (16)

Martin Luther had such a strong following in Germany the Emperor was reluctant to call for his arrest. Instead he was declared an outlaw. Luther returned to the protection of Frederick III of Saxony who had no intention of surrendering him to the Catholic authorities to be burnt or hanged. Luther went to live in Wartburg Castle where he began to translate the New Testament into German. (17)

There had been German versions of the Bible for nearly 50 years but they were of poor quality and were considered unreadable. Luther faced the basic problem of every translator: that of converting the original into the idioms and thought patterns of his own day. Luther's first version of the New Testament was published in September, 1522. It was immediately banned and people faced the possibility of arrest, imprisonment and death by owning, reading and selling copies of Luther's Bible. (18)

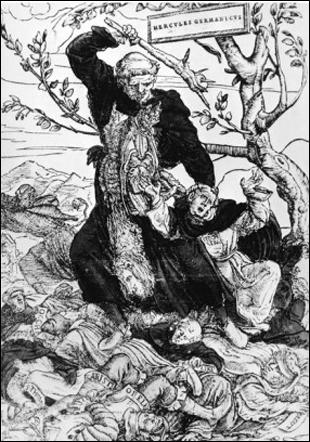

Hans Holbein was commissioned to create an image of Martin Luther. Published in 1523 it depicted Luther as the Greek super-hero and god, Hercules, attacking people with a viciously spiked club. In the picture, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, Duns Scotus and Nicholas of Lyra already lay bludgeoned to death at his feet and the German inquisitor, Jacob van Hoogstraaten was about to receive his fatal stroke. Suspended from a ring in Luther's nose was the figure of Pope Leo X. (19)

The author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "What was clever about this print (and what has made it difficult for later ages to determine its true message) was that it was capable of various interpretations. Followers of Luther could see their champion represented as a truly god-like being of awesome power, the agent of divine vengeance. Classical scholars, delighting in the many subtle allusions (such as the representation of the triple-tiaraed pope as the three-bodied monster, Geryon) could applaud the vivid representation of Luther as the champion of falsehood over medieval error. Yet, papalists could look on the same image and see in it a vindication of Leo's description of the uncouth German as the destructive wild boar in the vineyard and, for this reason, the engraving received a very mixed reception in Wittenberg." (20)

John Wycliffe & the Lollards

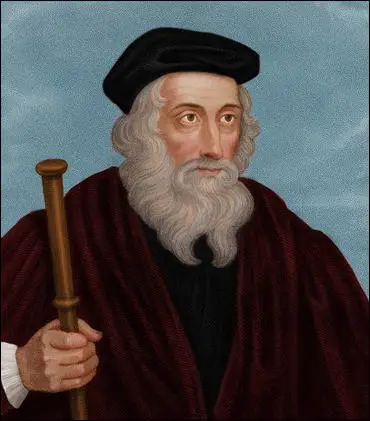

Martin Luther's views on the Roman Catholic Church were not new. In the 14th century, John Wycliffe and his followers had said similar things in England. Wycliffe antagonized the orthodox Church by disputing transubstantiation, the doctrine that the bread and wine become the actual body and blood of Christ. Wycliffe developed a strong following and those who shared his beliefs became known as Lollards. They got their name from the word "lollen", which signifies to sing with a low voice. The term was applied to heretics because they were said to communicate their views in a low muttering voice. (21)

In a petition later presented to Parliament, the Lollards claimed: "That the English priesthood derived from Rome, and pretending to a power superior to angels, is not that priesthood which Christ settled upon his apostles. That the enjoining of celibacy upon the clergy was the occasion of scandalous irregularities. That the pretended miracle of transubstantiation runs the greatest part of Christendom upon idolatry. That exorcism and benedictions pronounced over wine, bread, water, oil, wax, and incense, over the stones for the altar and the church walls, over the holy vestments, the mitre, the cross, and the pilgrim's staff, have more of necromancy than religion in them.... That pilgrimages, prayers, and offerings made to images and crosses have nothing of charity in them and are near akin to idolatry." (22)

It is believed that John Wycliffe and his followers began translating the Bible into English. Henry Knighton, the canon of St Mary's Abbey, Leicester, reported disapprovingly: "Christ delivered his gospel to the clergy and doctors of the church, that they might administer it to the laity and to weaker persons, according to the states of the times and the wants of men. But this Master John Wycliffe translated it out of Latin into English, and thus laid it out more open to the laity, and to women, who could read, than it had formerly been to the most learned of the clergy, even to those of them who had the best understanding. In this way the gospel-pearl is cast abroad, and trodden under foot of swine, and that which was before precious both to clergy and laity, is rendered, as it were, the common jest of both. The jewel of the church is turned into the sport of the people, and what had hitherto been the choice gift of the clergy and of divines, is made for ever common to the laity." (23)

In September 1376, Wycliffe was summoned from Oxford by John of Gaunt to appear before the king's council. He was warned about his behaviour. Thomas Walsingham, a Benedictine monk at St Albans Abbey, reported that on 19th February, 1377, Wycliffe was told to appear before Archbishop Simon Sudbury and charged with seditious preaching. Anne Hudson has argued: "Wycliffe's teaching at this point seems to have offended on three matters: that the pope's excommunication was invalid, and that any priest, if he had power, could pronounce release as well as the pope; that kings and lords cannot grant anything perpetually to the church, since the lay powers can deprive erring clerics of their temporalities; that temporal lords in need could legitimately remove the wealth of possessioners." On 22nd May 1377, Pope Gregory XI issued five bulls condemning the views of John Wycliffe. (24)

In 1382 Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and was forced into retirement. (25) Archbishop William Courtenay urged Parliament to pass a Statute of the Realm against preachers such as Wycliffe: "It is openly known that there are many evil persons within the realm, going from county to county, and from town to town, in certain habits, under dissimulation of great holiness, and without the licence ... or other sufficient authority, preaching daily not only in churches and churchyards, but also in markets, fairs, and other open places, where a great congregation of people is, many sermons, containing heresies and notorious errors." (26)

John Wycliffe died in Ludgershall on 31st December, 1384. Barbara Tuchman has claimed that John Wycliffe was the first "modern man". She goes on to argue: "Seen through the telescope of history, he (Wycliffe) was the most significant Englishman of his time." (27) After Wycliffe's death, his followers had to keep their views secret.

In 1414 there was a Lollard uprising led by John Oldcastle. It was reported by William Gregory: "On Twelve night... certain persons called Lollards... under cover... attempted to destroy the King and Holy Church... Sir Roger of Acton, and he was drawn and hanged beside St Giles for the King let to be made four pair of gallows, the which that were called the Lollards' gallows. Also... Sir John Beverley, and a squire of Oldcastle's John Brown, they were hanged; and many more were hanged and burnt, to the number of thirty-eight persons and more... And that same year were burnt in Smithfield... John Clayton, skinner, and Richard Turmyn, baker, for heresy." (28)

Over sixty Lollards were tried for heresy between 1428-31 in Norwich. Margery Baxter was accused of telling a friend that she denied the bread consecrated in the mass was the very body of Christ, "for if every such sacrament were God, and the very body of Christ, "for if every such sacrament were God, and the very body of Christ, there should be an infinite number of gods, because that a thousand priests and more do every day make a thousand such gods, and afterwards eat them, and void them out again in places where... you may find many such gods." Baxter went on to argue that "the images which stand in the churches" came from the Devil "so that the people worshipping those images commit idolatry". (29)

Reformation in England

It has been argued that the Lollards that survived these purges embraced the ideas of Martin Luther. His ideas had a major impact on young men studying to be priests in England. Students at Cambridge University would meet at the White Horse tavern. It was nicknamed "Little Germany" as the Lutheran creed was discussed within its walls, and the participants were known as "Germans". Those involved in the debates about religious reform included Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Shaxton and Matthew Parker. These students also went to hear the sermons of preachers such as Robert Barnes and Thomas Bilney. (30)

If the Pope could be wrong about indulgences, Luther argued he could be wrong about other things. For hundreds of years popes had only allowed bibles to be printed in Latin or Greek. Luther pointed out that only a minority of people in Germany could read these languages. Therefore to find out what was in the Bible they had to rely on priests who could read and speak Latin or Greek. Luther, on the other hand, wanted people to read the Bible for themselves.

Luther also began work on what proved to be one of his foremost achievements - the translation of the New Testament into the German vernacular. "This task was an obvious ramification of his insistence that the Bible alone is the source of Christian truth and his related belief that everyone is capable of understanding the biblical message. Luther’s translation profoundly affected the development of the written German language. The precedent he set was followed by other scholars, whose work made the Bible widely available in the vernacular and contributed significantly to the emergence of national languages." (31)

Influenced by Luther's writings, William Tyndale began work on an English translation of the New Testament. This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. (32) In 1523 he travelled to London for a meeting with Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London. Tunstall refused to support Tyndale in this venture but did not organize his persecution. Tyndale later wrote that he now realized that "to translate the New Testament… there was no place in all England" and left for Germany in April 1524.

Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms. (33)

Tyndale's Bible was heavily influenced by the writings of Martin Luther. This is reflected in the way he altered the meaning of certain important concepts. "Congregation" was employed instead of "church", and "senior" instead of "priest", "penance", "charity", "grace" and "confession" were also silently removed. (34) Melvyn Bragg has pointed out. Tyndale "loaded our speech with more everyday phrases than any other writer before or since". This included “under the sun”, “signs of the times”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “lick the dust”, “fall flat on his face”, “the land of the living”, “pour out one’s heart”, “the apple of his eye”, “fleshpots”, “go the extra mile” and “the parting of the ways”. Bragg adds: "Tyndale deliberately set out to write a Bible which would be accessible to everyone. To make this completely clear, he used monosyllables, frequently, and in such a dynamic way that they became the drumbeat of English prose." (35)

The Peasants' War

Martin Luther had been born a peasant and he was sympathetic to their plight in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. Thomas Müntzer was a follower of Luther and argued that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society". (36)

In August 1524, Müntzer became one of the leaders of the uprising later known as the German Peasants' War. In one speech he told the peasants: "The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: 'God has commanded that thou shalt not steal'. Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang." (37)

The following year Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Mühlhausen town council and setting up a type of communistic society. By the spring of 1525 the rebellion, known as the Peasants’ War, had spread to much of central Germany. The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto titled The Twelve Articles of the Peasants; the document is notable for its declaration that the rightness of the peasants’ demands should be judged by the Word of God, a notion derived directly from Luther’s teaching that the Bible is the sole guide in matters of morality and belief. (38)

Although he agreed with many of the peasants' demands but he hated armed strife. He travelled round the country districts, risking his life to preach against violence. Martin Luther also published the tract, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants, where he urged the princes to "brandish their swords, to free, save, help, and pity the poor people forced to join the peasants - but the wicked, stab, smite, and slay all you can." Some of the peasant leaders reacted to the tract by describing Luther as a spokesman for the oppressors. (39)

Thomas Müntzer led about 8,000 peasants into battle in Frankenhausen on 15th May 1525. Müntzer told the peasants: "Forward, forward, while the iron is hot. Let your swords be ever warm with blood!" Armed with mostly scythes and flails they stood little chance against the well-armed soldiers of Philip I of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony. The combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack resulted in the peasants fleeing in panic. Over 3,000 peasants were killed whereas only four of the soldiers lost their lives. Müntzer was captured, tortured and finally executed on 27th May, 1525.His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who might again preach treasonous doctrines. (40)

Marriage of Priests

Luther also tackled the subject of priests and marriage. He argued out that nowhere in the Bible was the celibacy of priests commanded nor their marriage forbidden. He pointed out that all the apostles except John were married, and that the Bible portrays Paul as a widower. Luther went on to suggest that the prohibition of marriage increased sin, shame, and scandal without end. He quoted from Paul’s First Epistle to Timothy to justify his position: “A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt to teach; not given to wine, no striker, not greedy of filthy lucre; but patient, not a brawler, not covetous.” Luther denied that this or any other pope had any standing whatever to legislate human sexuality. “Does the pope set up laws?” he had asked in one essay. “Let him set them up for himself and keep hands off my liberty.” (41)

Katherine von Bora was one of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, when he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels. She was a woman from a noble family who had been placed in the convent as a child. For the next two years she worked as a servant in the house of the artist, Lucas Cranach. According to Derek Wilson: "Catherine was comely (perhaps even plain); she was intelligent; and she had a mind of her own. She set her face against being married off to the first man who would have her.... At length a suitor was found who did please her. This was Jerome Baumgartner, a wealthy, young burger from Nuremberg. Sadly, Baumgartner's family persuaded him that he could do better for himself and a disconsolate Catherine was left on the shelf." (42)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Martin Luther then tried to arrange for Katherine to marry Casper Glatz, a fellow theologian. She appealed to Nicolaus von Amsdorf and he wrote to his friend on her behalf: "What in the devil are you up to that you try to persuade good Kate and force that old skinflint, Glatz, on her. She doesn't go for him and has neither love nor affection for him." Catherine made it clear that she wanted to marry Luther. (43)

On a visit to his parents, Luther's father asked him: how long was Martin going to go on advising other ex-monks to marry while refusing to set an example himself. On 13th June 13, 1525, Luther married Katherine. Hans J. Hillerbrand has argued that this decision was based on a number of factors. This included the fact that he regarded the Roman Catholic Church’s insistence on clerical celibacy as the work of the Devil. (44)

Martin Luther explained his decision in a letter to Nicolaus von Amsdorf: "The rumour is true that I was suddenly married to Katherine. I did this to silence the evil mouths which are so used to complaining about me... In addition, I also did not want to reject this unique opportunity to obey my father's wish for progeny, which he so often expressed. At the same time I also wanted to confirm what I have taught by practising it; for I find so many timid in spite of such great light from the gospel. god has willed and brought about this step. For I feel neither passionate love nor burning desire for my spouse." (45)

Augsburg Confession

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 Philipp Melanchthon was the leading representative of the Reformation, and it was he who prepared the Augsburg Confession, which influenced other credal statements in Protestantism. In the Confession he sought to be as inoffensive to the Catholics as possible while forcefully stating the Evangelical position. As Klemens Löffler has pointed out: "He was not qualified to play the part of a leader amid the turmoil of a troublous period. The life which he was fitted for was the quiet existence of the scholar. He was always of a retiring and timid disposition, temperate, prudent, and peace-loving, with a pious turn of mind and a deeply religious training. He never completely lost his attachment for the Catholic Church and for many of her ceremonies.... He invariably sought to preserve peace as long as might be possible." (46)

Martin Luther wrote a pamphlet, Exhortation to all Clergy Assembled at Augsburg that caused Melanchthon considerable distress: "You are the devil's church! She (the Catholic Church) is a liar against God's word and a murderess, for she sees that her god, the devil, is also a liar and a murderer... We want you to be forced to it by God's word and have you worn down like blasphemers, persecutors and murderers, so that you humble yourself before God, confess your sins, murder and blasphemy against God's word." (47)

Luther had the pamphlet printed and 500 copies sent to Augsburg. As Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) pointed out: "While Melanchthon and the others were making serious efforts to reach a compromise solution, their mentor, like some prophet of old, was despatching from his mountain retreat messages of fiery denunciation and exhortations to his friends to stick to their guns." (48)

Melanchthon's Apology of the Confession of Augsburg (1531) became an important document in the history of Lutherism. Melanchthon was accused of being too willing to compromise with the Catholic Church. However, he argued: "I know that the people decry our moderation; but it does not become us to heed the clamour of the multitude. We must labour for peace and for the future It will prove a great blessing for us all if unity be restored in Germany." (49)

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has written in some detail about the relationship between Luther and Melanchthon: "Melanchthon, seeing Luther's faults and regretting them, admired him with a rueful affection and reverenced him as the restorer of truth in the Church. His respect for tradition and authority suited Luther's underlying conservatism, and he supplied learning, a systematic theology, a mode of education, an ideal for the universities, and an even and tranquil spirit." (50)

The German Bible

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has pointed out: "He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote". (51)

The translation of the Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534. Luther worked closely with Philipp Melanchthon, Johannes Bugenhagen, Caspar Creuziger and Matthäus Aurogallus on the project. There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg. This included the work of Lucas Cranach.

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "With the New Testament Luther staked a place at the very forefront of the development of German literature. His style was vigorous, colourful and direct. Anyone reading it could almost hear the author proclaiming the sacred text and that was no fortuitous accident; Luther's written language was akin to the oral delivery of his own impassioned sermons. His translation was couched in compelling prose." (52)

Martin Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). He also commissioned Cranach to provide cartoon illustrations for his German translation of the New Testament, which became a best seller, a major event in the history of the Reformation. (53)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

In October 1532 Henry VIII appointed Thomas Cranmer as the next Archbishop of Canterbury. Eustace Chapuys sent a report to Emperor Charles V that he believed that Cranmer was a supporter of Martin Luther. (54) This was in fact true and earlier that year he had during a diplomatic mission to Germany, Cranmer befriended the leading Lutheran theologian, Andreas Osiander. At some stage during his time in Germany, probably in July, married Margaret, a niece of Osiander's wife, Katharina Preu. This act reflects Cranmer willingness to reject the old church's tradition of compulsory celibacy. (55)

Henry's confidence in Cranmer was reflected by the decision to appoint him as a royal chaplain and he was attached to the household of Thomas Boleyn, the father of his mistress, Anne Boleyn. In December 1532 Henry discovered that Anne was pregnant. He realised he could not afford to wait for the Pope's permission to marry Anne. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married in secret. Cranmer later confirmed that the marriage ceremony took place on 25th January, 1533. (56)

Thomas Cranmer was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury in St Stephen's Church at Westminster on 30th March 1533. It was a necessary part of of the consecration ceremony that the Archbishop should take an oath, swearing to be obedient to Pope Clement VII and his successors and to defend the Roman Papacy against all men. This raised a problem for Henry. He wanted Cranmer's consecration ceremony to be correct in every detail, so that no one could claim that he had not been properly consecrated. This was because he intended in a few weeks time for Cranmer to state that the Pope had no authority in England.

Henry and his Archbishop of Canterbury eventually came up with a solution to the problem. Before entering the church, Cranmer made a statement in the chapter house at Westminster, in the presence of five lawyers. He declared that he did not intend to be bound by the oath of obedience to the Pope that he was about to take, "if it was against the law of God or against our illustrious King of England, or the laws of his realm of England". (57)

Act of Supremacy

Pope Clement VII announced that Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn was invalid. Henry reacted by declaring that the Pope no longer had authority in England. In November 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This gave Henry the title of the "Supreme head of the Church of England". A Treason Act was also passed that made it an offence to attempt by any means, including writing and speaking, to accuse the King and his heirs of heresy or tyranny. All subjects were ordered to take an oath accepting this. (58)

Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused to take the oath and were imprisoned in the Tower of London. More was summoned before Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell at Lambeth Palace. More was happy to swear that the children of Anne Boleyn could succeed to the throne, but he could not declare on oath that all the previous Acts of Parliament had been valid. He could not deny the authority of the pope "without the jeoparding of my soul to perpetual damnation." (59)

Henry's daughter, Mary I, also refused to take the oath as it would mean renouncing her mother, Catherine of Aragon. On hearing this news, Anne Boleyn apparently said that the "cursed bastard" should be given "a good banging". Henry told Cranmer that he had decided to send her to the Tower of London, and if she refused to take the oath, she would be prosecuted for high treason and executed. According to Ralph Morice it was Cranmer who finally persuaded Henry not to put her to death. Morice claims that when Henry at last agreed to spare Mary's life, he warned Cranmer that he would live to regret it. (60) Henry decided to put her under house arrest and did not allow her to have contact with her mother. He also sent some of her servants who were sent to prison.

Religious Reforms

In July 1537, a committee of bishops, archdeacons and Doctors of Divinity, headed by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, published The Institution of the Christian Man (also called The Bishops' Book). The purpose of the work was to implement the reforms of Henry VIII in separating from the Roman Catholic Church. Henry did not attend the discussions, but took an active part in producing the book. He studied the proposed drafts, suggested amendments and argued about the precise theological significance of one word compared to another.

The book repeatedly proclaimed the royal supremacy over the Church and the duty of all good subjects to obey the King. For example, "Thou shalt not kill" meant that no one should kill except the reigning monarch and those acting under their orders. This meant that Henry and future monarchs were "above the law of the realm". Henry tried to change it to state that "inferior rulers" should not have the same rights as kings like himself. Cranmer thought that this change would be undesirable and it was not altered. (61)

Thomas Cranmer, Thomas Cromwell and Hugh Latimer joined forces to introduce religious reforms. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and ordered to be burnt at the stake by Henry VIII eleven years before, for producing such a Bible. The edition they wanted to use was that of Miles Coverdale, an edition that was a reworking of the one produced by Tyndale. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England. (62)

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." (63) Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." (64)

David Starkey has praised the way that Cranmer was able to adapt his religious views during his period of power: "What Cranmer lacked in brilliance, he made up for in steadiness; he was thorough, organized and a superb note-taker. In contrast with the instinctively partisan Gardiner, he was also blessed (and sometimes cursed) with an ability to see both sides of the question. This, combined with his essential fair-mindedness, meant that his opinions were in a state of slow but constant change. The individual steps were scarcely ever revolutionary. But his lifetime's journey - from orthodoxy to advanced reform - was." (65)

Reign of Edward VI

When Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. Edward was too young to rule, so his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, took over the running of the country. At the beginning of the new reign Archbishop Thomas Cranmer grew a beard. "This may be seen as a token of mourning for his old master, but in fact the clergy of the reformed Church favoured beards; it may be seen as a decisive rejection of the tonsure and of the clean-shaven popish priests." (66)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer fully supported the religious direction of the new government and invited several Protestant reformers to England. Cranmer now openly acknowledged his married state. At Edward's coronation Cranmer gave a short address that was a forceful statement of royal supremacy against Rome, as well as an emphatic call to the young king to become a destroyer of idolatry. (67)

Attempts were made to destroy those aspects of religion that were associated with the Catholic Church, for example, the removal of stained-glass windows in churches and the destruction of religious wall-paintings. Somerset made sure that Edward VI was educated as a Protestant, as he hoped that when he was old enough to rule he would continue the policy of supporting the Protestant religion.

Somerset's programme of religious reformation was accompanied by bold measures of political, social, and agrarian reform. Legislation in 1547 abolished all the treasons and felonies created under Henry VIII and did away with existing legislation against heresy. Two witnesses were required for proof of treason instead of only one. Although the measure received support in the House of Commons, its passage contributed to Somerset's reputation for what later historians perceived as his liberalism. (68)

In 1548 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer converted the Mass into Communion and constructed a new Prayer Book. These events upset those conservatives such as Bishop Stephen Gardiner who pointed out that some of his actions were considered to be heretical. Princess Mary was also concerned by these developments and wrote a letter to Lord Protector Edward Seymour to protest against the direction of events. (69)

The Kett Rebellion took place in the summer of 1549. Lord Protector Edward Seymour was blamed by the nobility and gentry for the social unrest. They believed his statements about political reform had encouraged rebellion. His reluctance to employ force and refusal to assume military leadership merely made matters worse. Seymour's critics also disliked his popularity with the common people and considered him to be a potential revolutionary. His main opponents, including John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, Henry Wriothesley, 2nd Earl of Southampton, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, and Ralph Sadler met in London to demand his removal as Lord Protector. (70)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer supported the Duke of Somerset but few others took his side. (71) Seymour no longer had the support of the aristocracy and had no choice but to give up his post. On 14th January 1550 his deposition as lord protector was confirmed by act of parliament, and he was also deprived of all his other positions, of his annuities, and of lands to the value of £2000 a year. He was sent to the Tower of London where he remained until the following February, when he was released by the Earl of Warwick who was now the most powerful figure in the government. Roger Lockyer suggests that this "gesture of conciliation on Warwick's part served its turn by giving him time to gain the young King's confidence and to establish himself more firmly in power". (72) This upset the nobility and in October 1551, Warwick was forced to arrest the Duke of Somerset.

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, pleaded not guilty to all charges against him. He skillfully conducted his own defence and was acquitted of treason but found guilty of felony under the terms of a recent statute against bringing together men for a riot and sentenced to death. (73) "Historians sympathetic to Somerset argue that the indictment was largely fictitious, that the trial was packed with his enemies, and that Northumberland's subtle intrigue was responsible for his conviction. Other historians, however, have noted that Northumberland agreed that the charge of treason should be dropped and that the evidence suggests that Somerset was engaged in a conspiracy against his enemies." (68) Although the king had supported Somerset's religious policies with enthusiasm he did nothing to save him from his fate and he was executed on 22nd January, 1552. (74)

Attempts were made by conservatives on the Privy Council to engineer the execution of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick. The two men formed an alliance and managed to keep control of the government. According to his biographer, Diarmaid MacCulloch "from now on evangelical ascendancy was unchallenged". (75) In 1559 there were further revisions of the Prayer Book. "Cranmer's second prayer book remains at the heart of all Anglican liturgical forms. (76)

Primary Sources

(1) Owen Chadwick, The Reformation (1964)

He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote.

(2) Derek Wilson, Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007)

With the New Testament Luther staked a place at the very forefront of the development of German literature. His style

was vigorous, colourful and direct. Anyone reading it could almost hear the author proclaiming the sacred text and that was no fortuitous accident; Luther's written language was akin to the oral delivery of his own impassioned sermons. His translation was couched in compelling prose. But what did it compel - or entreat - people to believe?This was no objective rendering of a Greek original into a sixteenth-century vernacular. Having, as he believed, fathomed the "true" gospel, Luther was intent on communicating his insights to others. Each book was provided with its own preface and marginal glosses,, designed to instruct the reader in the understanding of all the key concepts - "law", "grace", "sin", "faith", "righteousness", etc. Anti-Roman polemic also had its place in the new translation.

Luther did not hesitate to point out the contemporary application of first-century teaching. For example, the papacy was clearly identified as the beast of Revelation in Luther's glosses and the vivid woodcuts provided by Lucas Cranach. Luther's New Testament was the campaign manual of the Reformation...

This phenomenon that appeared in England a few years later had its beginning in Germany in the early 1520s. Bible mania is something the modern reader may well find difficult to understand. In an age when the Bible remains the least read best-seller and is widely regarded as out-dated and irrelevant we find it hard to get inside the minds of people who risked arrest, imprisonment and death by owning, reading and selling copies of the sacred text. Luther's New Testament was, of course, banned and, of course, that only boosted sales. For young scholars and other radically minded people the fact that this fruit was forbidden only added piquancy to its taste. Like Tyndale's English version a few years later, the book attracted excited, devoted students. The lengths the authorities went to to lay their hands on smuggled volumes is testimony to its success. The emperor ordered all copies to be handed in and some senior ecclesiastics even offered to pay for the books thus surrendered. Not many were.

Why did this translation, coming when it did, strike such a common chord? It was because books were, for the first time, becoming part of the everyday experience of people's lives. For some they were, doubtless, little more than status symbols - statements of their owners' wealth and sophistication. But for others they opened whole new worlds of knowledge and imagination hitherto available only to the well-educated (primarily senior clergy and the sons of aristocrats). An extensive "middle class" could now afford to buy what was coming from the presses. And the most intriguing book of all was the Bible. For as long as anyone could remember priests and friars had talked about it, theologians had argued about it, artists had represented scenes from it in paint and stained glass and now the controversy over what it actually meant had "hit the headlines". It was news. Small wonder, then, that people flocked to acquire copies, to become literate in order to read them or to resort secretly to the homes of neighbours where the forbidden words were expounded. Bible study became a swelling, unstoppable underground movement. Scripture written in language that ordinary literate people could understand emerged as the symbol and guarantor of personal freedom. Men and women no longer had to take their religion from the priest, to accept uncritically "truths" proclaimed by men for whom they had limited respect. They could read the Gospel for themselves, interpret it at will, and even write their own religious tracts, expounding and applying holy writ. As we shall see, one result of the publication of Lutheran Bibles was the releasing of a flood of books and pamphlets written by laymen (and women!). Merchants, artisans, soldiers and housewives turned into theologians and rushed into print.

But it was.not just the serum of a purified biblical text that Luther set coursing through the veins of Germany. Translation implies interpretation and it was his exposition of the New Testament message that made such a dramatic impact. In the introductory notes and the marginal glosses he wrote for the New Testament books Luther identified and laid out the methodology that later ages would call "Evangelicalism". This was far and away the most important contribution of Martin Luther to the history of religion...

(3) Victor S. Navasky, The Art of Controversy (2012)

Hans Holbein... created a woodcut depicting Martin Luther as "the German Hercules," in which Luther beats scholastics as Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas into submission with a nail-studded club.

Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). He also commissioned Cranach to provide cartoon illustrations for his German translation of the New Testament, which became a best seller, a major event in the history of the Reformation.

(4) Thomas Müntzer was a German supporter of Martin Luther. In 1525 he led a Peasants' Revolt in Saxony. Before he was executed, Muntzer explained his religious views.

The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: "God has commanded that thou shalt not steal". Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang.

(5) Hans J. Hillerbrand, Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

Luther’s role in the Reformation after 1525 was that of theologian, adviser, and facilitator but not that of a man of action. Biographies of Luther accordingly have a tendency to end their story with his marriage in 1525. Such accounts gallantly omit the last 20 years of his life, during which much happened. The problem is not just that the cause of the new Protestant churches that Luther had helped to establish was essentially pursued without his direct involvement, but also that the Luther of these later years appears less attractive, less winsome, less appealing than the earlier Luther who defiantly faced emperor and empire at Worms. Repeatedly drawn into fierce controversies during the last decade of his life, Luther emerges as a different figure - irascible, dogmatic, and insecure. His tone became strident and shrill, whether in comments about the Anabaptists, the pope, or the Jews. In each instance his pronouncements were virulent: the Anabaptists should be hanged as seditionists, the pope was the Antichrist, the Jews should be expelled and their synagogues burned. Such were hardly irenic words from a minister of the gospel, and none of the explanations that have been offered - his deteriorating health and chronic pain, his expectation of the imminent end of the world, his deep disappointment over the failure of true religious reform - seem satisfactory.

Student Activities

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)