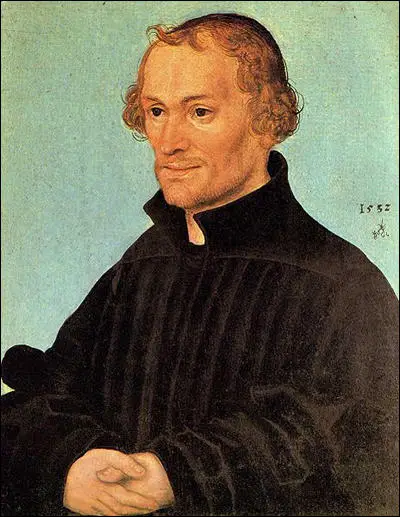

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon (original name Philipp Schwartzerd), the son of Georg Schwartzerd and Barbara Reuter, was born in Bretten, Germany, on 15th February, 1497.

After the death of his father in 1508 his great-uncle, Johannes Reuchlin, took over responsibility for his education. His first tutor instilled in him a lifelong love of Latin and Classical literature and had his name changed from Schwartzerd to its Greek equivalent, Melanchthon. (1)

Melanchthon was a talented student and at the age of twelve, he entered the University of Heidelberg. He obtained the baccalaureate in 1511, but his application for the master's degree in 1512 was rejected because of his youth. He therefore went to University of Tübingen, where his thirst for knowledge led him into jurisprudence, mathematics and medicine. (2)

On receiving the M.A. degree, he taught at the university. He also wrote several books and his work was praised by Desiderius Erasmus. Melanchthon gained the reputation as a religious reformer and this hurt his academic career. His great-uncle recommended him to Martin Luther and in 1518 became professor of Greek at University of Wittenberg. (3)

Philipp Melanchthon and Martin Luther

Over the next few years Melanchthon became a loyal follower of Luther. Clyde L. Manschreck has pointed out: "Luther, the founder of the Protestant Reformation, and Melanchthon responded to each other enthusiastically, and their deep friendship developed. Melanchthon committed himself wholeheartedly to the new Evangelical cause, initiated the previous year when Luther circulated his Ninety-five Theses. By the end of 1519 he had already defended scriptural authority against Luther’s opponent Johann Eck, rejected (before Luther did) transubstantiation - the doctrine that the substance of the bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper is changed into the body and blood of Christ - made justification by faith the keystone of his theology, and openly broken with Reuchlin." (4)

In 1520 Martin Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation. In the tract he argued that the clergy were unable or unwilling to reform the Church. He suggested the kings and princes must step in and carry out this task. Luther went on to claim that reform is impossible unless the Pope's power in Germany is destroyed. He urged them to bring an end to the rule of clerical celibacy and the selling of indulgences. "The German nation and empire must be freed to live their own lives. The princes must make laws for the moral reform of the people, restraining extravagance in dress or feasts or spices, destroying the public brothels, controlling the bankers and credit." (5)

Humanists like Desiderius Erasmus had criticised the Catholic Church but Luther's attack was very different. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "From the beginning there was a fundamental difference between Erasmus and Luther, between the humanists and the Lutherans. The humanists wished to remove the corruptions and to reform the Church in order to strengthen it; the Lutherans, almost from the beginning, wished to overthrow the Church, believing that it had become incurably wicked and was not the Church of Christ on earth." (6)

On 15th June 1520, Pope Leo X issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against the Pope. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!" (7)

University of Wittenberg

It seems that Melanchthon energy was phenomenal. He began his day at 2:00 am and gave lectures, often to as many as 600 students, at 6:00. His theological courses were followed by as many as 1500 students. He also found time to court Katherine Krapp, whom he married in 1520 and who bore him four children - Anna, Philipp, Georg, and Magdalen. (8)

Melanchthon persistently refused the title of Doctor of Divinity, and never accepted ordination; nor was he ever known to preach. His desire was to remain a humanist, and to the end of his life he continued his work on the classics. He composed the first treatise on "evangelical" doctrine in 1521. It deals principally with practical religious questions, sin and grace, law and gospel, justification and regeneration. (9)

It has been claimed that this was the first systematic treatment of Protestant Reformation thought. "Drawing on scripture, Melanchthon argued that sin is more than an external act; it reaches beyond reason into human will and emotions so that the individual human cannot simply resolve to do good works and earn merit before God. Original sin is a native propensity, an inordinate self-concern tainting all man’s actions. But God’s grace consoles man with forgiveness, and man’s works, though imperfect, are a response in joy and gratitude for divine benevolence." (10)

The Peasant War

Martin Luther had been born a peasant and he was sympathetic to their plight in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. In December 1521 he warned that the peasants were close to rebellion: "Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man... is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do." (11)

Thomas Müntzer was a follower of Luther and argued that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society". (12)

In August 1524, Müntzer became one of the leaders of the uprising later known as the Peasants’ War. In one speech he told the peasants: "The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: 'God has commanded that thou shalt not steal'. Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang." (13)

The following year Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Mühlhausen town council and setting up a type of communistic society. By the spring of 1525 the rebellion had spread to much of central Germany. The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto titled The Twelve Articles of the Peasants; the document is notable for its declaration that the rightness of the peasants’ demands should be judged by the Word of God, a notion derived directly from Luther’s teaching that the Bible is the sole guide in matters of morality and belief. (14)

Some of Luther's critics blamed him for the Peasants' War: "The peasant outbreaks, which in milder forms were previously easily controlled, now assumed a magnitude and acuteness that threatened the national life of Germany.... A fire of repressed rebellion and infectious unrest burned throughout the nation. This smouldering fire Luther fanned to a fierce flame by his turbulent and incendiary writings, which were read with avidity by all, and by none more voraciously than the peasant, who looked upon 'the son of a peasant' not only as an emancipator from Roman impositions, but the precursor of social advancement." (15)

Although it is true that Martin Luther he agreed with many of the peasants' demands, he hated armed strife. He travelled round the country districts, risking his life to preach against violence. Martin Luther also published the tract, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants, where he urged the princes to "brandish their swords, to free, save, help, and pity the poor people forced to join the peasants - but the wicked, stab, smite, and slay all you can." Some of the peasant leaders reacted to the tract by describing Luther as a spokesman for the oppressors. (16)

In the tract Luther made it clear that he now had no sympathy for the rebellious peasants: "The pretences which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil's work that they are at.... They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands... Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do."

Luther called on the nobility of Germany to destroy the rebels: "They (the peasants) are starting a rebellion, and violently robbing and plundering monasteries and castles which are not theirs, by which they have a second time deserved death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers ... if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man. For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster." (17)

Martin Luther wrote to Philipp Melanchthon asking his for his support in this struggle: "I hear of nothing said or done by them that Satan could not also do or imitate... God has never sent anyone, not even the Son himself, unless he was called through men or attested by signs... I have always expected Satan to touch this sore, but he did not want to do it through the papists. It is among us and among our followers that he is stirring up this grievous schism, but Christ will quickly trample hum under our feet." (18)

Augsburg Confession

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 Melanchthon was the leading representative of the Reformation, and it was he who prepared the Augsburg Confession, which influenced other credal statements in Protestantism. In the Confession he sought to be as inoffensive to the Catholics as possible while forcefully stating the Evangelical position. As Klemens Löffler has pointed out: "He was not qualified to play the part of a leader amid the turmoil of a troublous period. The life which he was fitted for was the quiet existence of the scholar. He was always of a retiring and timid disposition, temperate, prudent, and peace-loving, with a pious turn of mind and a deeply religious training. He never completely lost his attachment for the Catholic Church and for many of her ceremonies.... He invariably sought to preserve peace as long as might be possible." (19)

Martin Luther wrote a pamphlet, Exhortation to all Clergy Assembled at Augsburg that caused Melanchthon considerable distress: "You are the devil's church! She (the Catholic Church) is a liar against God's word and a murderess, for she sees that her god, the devil, is also a liar and a murderer... We want you to be forced to it by God's word and have you worn down like blasphemers, persecutors and murderers, so that you humble yourself before God, confess your sins, murder and blasphemy against God's word." (20)

Luther had the pamphlet printed and 500 copies sent to Augsburg. As Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) pointed out: "While Melanchthon and the others were making serious efforts to reach a compromise solution, their mentor, like some prophet of old, was despatching from his mountain retreat messages of fiery denunciation and exhortations to his friends to stick to their guns." (21)

Melanchthon's Apology of the Confession of Augsburg (1531) became an important document in the history of Lutherism. Melanchthon was accused of being too willing to compromise with the Catholic Church. However, he argued: "I know that the people decry our moderation; but it does not become us to heed the clamour of the multitude. We must labour for peace and for the future It will prove a great blessing for us all if unity be restored in Germany." (22)

German Bible

Philipp Melanchthon continued to work closely with Martin Luther on other issues. "He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote". (23)

The translation of the Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534. Johannes Bugenhagen, Caspar Creuziger and Matthäus Aurogallus worked with Melanchthon and Luther on the project. There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg. This included the work of Lucas Cranach. This included "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). (24)

Final Years

Martin Luther died on 18th February 1546. Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has argued: "After Luther's death the discrepancy between master and disciple became a difficulty, arousing argument and dividing loyalties. As long as he lived, they complemented each other. Melanchthon, seeing Luther's faults and regretting them, admired him with a rueful affection and reverenced him as the restorer of truth in the Church. His respect for tradition and authority suited Luther's underlying conservatism, and he supplied learning, a systematic theology, a mode of education, an ideal for the universities, and an even and tranquil spirit." (25)

Melanchthon participated in the religious discussion which took place at Worms, in 1557, between Catholic and Protestant theologians. His attempts to reach a compromise resulted in attacks from people within the Lutheran movement. It is claimed that during his final illness he told a friend that the reason for not fearing death: "thou shalt be freed from the theologians' fury." (26)

Philipp Melanchthon died on 19th April 1560.

Primary Sources

(1) Clyde L. Manschreck, Philipp Melanchthon: Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

Luther, the founder of the Protestant Reformation, and Melanchthon responded to each other enthusiastically, and their deep friendship developed. Melanchthon committed himself wholeheartedly to the new Evangelical cause, initiated the previous year when Luther circulated his Ninety-five Theses. By the end of 1519 he had already defended scriptural authority against Luther’s opponent Johann Eck, rejected (before Luther did) transubstantiation - the doctrine that the substance of the bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper is changed into the body and blood of Christ - made justification by faith the keystone of his theology, and openly broken with Reuchlin.

(2) Klemens Löffler, Philipp Melanchthon: The Catholic Encyclopedia (1911)

Luther was a strong believer in making humanism serve the cause of the "Gospel", and it was not long before the still plastic Melancthon fell under the sway of Luther's powerful personality.... For 42 years he laboured at Wittenberg in the very front rank of university professors. His theological courses were followed by 500 or 600, later by as many as 1500 students, whereas his philological lectures were often but poorly attended. Yet he persistently refused the title of Doctor of Divinity, and never accepted ordination; nor was he ever known to preach. His desire was to remain a humanist, and to the end of his life he continued his work on the classics, along with his exegetical studies....

But he was not qualified to play the part of a leader amid the turmoil of a troublous period. The life which he was fitted for was the quiet existence of the scholar. He was always of a retiring and timid disposition, temperate, prudent, and peace-loving, with a pious turn of mind and a deeply religious training. He never completely lost his attachment for the Catholic Church and for many of her ceremonies.... Later he invariably sought to preserve peace as long as might be possible.

(3) Owen Chadwick, The Reformation (1964)

The Augsburg Confession... was drafted by Philipp Melanchthon. The alliance between the two minds of Luther and Melanchthon, who between them moulded the Lutheran reform, is a facinating study, for they were unequal yoke-fellows. The vehemence of the one verses the pacific nature of the other; the pastoral soul verses the scholar and intellectual; the apostle of the poor and simple versus the apostle of higher education: the pilgrim marching to his God through clouds of demons and temptations versus the moderate student of truth; rough peasant manners versus gentle courtesy.

Student Activities

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)