Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner was born in Bury St Edmunds in about 1495. He was educated in Paris where he met Desiderius Erasmus. On his return to England in 1511 he studied at Cambridge University. After graduating in 1518 he taught at Trinity Hall. His pupils included Thomas Wriothesley and William Paget.

In 1524 Gardiner joined the staff of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. He also became a legal advisor to Henry VIII. Gardiner became involved in arranging the divorce of Catherine of Aragon. According to his biographer, C. D. C. Armstrong: "Gardiner was present at the formal inauguration of the proceedings for the divorce on 17 May 1527, and early in 1528 he was sent on embassy to the pope in the company of another rising Cambridge don, Edward Foxe (later bishop of Hereford)." (1)

Pope Clement VII told Gardiner that he had heard that the King wanted an annulment for private reasons only, being driven by "vain affection and undue love" for a lady far from worthy of him. Gardiner defended Henry, pointing out that he needed a male heir and arguing that Anne Boleyn was "animated by the noblest sentiments; the Cardinal of York and all England do homage to her virtues". Gardiner also claimed that Queen Catherine suffered from "certain diseases" which meant that Henry would never again live with her as his wife. These discussions took place over several weeks but Clement "dithered and procrastinated" and was unable to make a decision on Henry's marriage. (2)

In October 1528, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio arrived in England to discuss the issue with Cardinal Wolsey. Both men tried without success to persuade Catherine to acknowledge the invalidity of her marriage. In January 1529 Henry sent Gardiner to Rome with a "warning that unless a speedy and favourable decision was given by the two legates he would renounce his allegiance to the papal see." When these negotiations were unsuccessful, Wolsey was blamed and all his palaces and colleges were confiscated. (3) Gardiner was not blamed for this failure and in July 1529 was appointed as the King's principal secretary.

According to Jasper Ridley the English were famous throughout Europe for their hearty appetite. "It was said the English vice was overeating, as the German vice was drunkenness and the French vice lechery." (4) Stephen Gardiner had strong views on the subject. "Every country hath his peculiar inclination to naughtiness. England and Germany to the belly, the one in liquor, the other in meat; France a little beneath the belly; Italy to vanity and pleasures devised; and let an English belly have a further advancement, and nothing can stay it." (5)

Stephen Gardiner - Bishop of Winchester

In November 1531, the king rewarded Gardiner with the bishopric of Winchester, vacant since Wolsey's death. His biographer points out: "Still only in his thirties, he was now one of England's wealthiest and most important bishops, and his promotion marked him as one of Henry's leading servants." (6) With the help of Gardiner, by the spring of 1532 Henry VIII had "assumed supreme religious power in his own realm, and the English clergy had been terrorized into surrendering all their ancient, jealously-guarded freedom from secular control." (7)

However, there is evidence that Gardiner was having doubts about how much power the monarchy should have. In April 1532 Gardiner argued the divine origin of the church's right to make laws and denied that such laws were contingent upon royal approval. Henry was furious with Gardiner and meant that it was Thomas Cranmer who became the next Archbishop of Canterbury. It was therefore Cranmer who presided in April 1533 at the court that annulled Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Gardiner remained as Henry's close advisor and appeared in court as counsel for Henry and attended the coronation of Anne Boleyn in June. (8)

Gardiner no longer enjoyed the full confidence of Henry and by April 1534 he had been formally replaced as royal secretary by Thomas Cromwell. Gardiner sought his way back into the king's favour by writing in defence of the royal supremacy and of the execution of John Fisher in June 1535, the Bishop of Rochester, who had refused to accept the king as Supreme Head of the Church of England and for upholding the Catholic Church's doctrine of papal primacy. (9) This brought Gardiner back in favour and later that year he became Henry's ambassador to France.

Pilgrimage of Grace

Stephen Gardiner upset Henry again during the Pilgrimage of Grace crisis. In Yorkshire, in 1536, a lawyer named Robert Aske formed an army to defend the monasteries. The rebel army was joined by priests carrying crosses and banners. Leading nobles in the area also began to give their support to the rebellion. The rebels marched to York and demanded that the monasteries should be reopened. This march, which contained over 30,000 people, became known as the Pilgrimage of Grace.

Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, was sent to Lincolnshire to deal with the rebels. In a age before a standing army, loyal forces were not easy to raise. (10) "Appointed the king's lieutenant to suppress the Lincolnshire rebels, he advanced fast from Suffolk to Stamford, gathering troops as he went; but by the time he was ready to fight, the rebels had disbanded. On 16th October he entered Lincoln and began to pacify the rest of the county, investigate the origins of the rising, and prevent the southward spread of the pilgrimage, still growing in Yorkshire and beyond. Only two tense months later, as the pilgrims dispersed under the king's pardon, could he disband his 3600 troops and return to court." (11)

Henry VIII's army was not strong enough to fight the rebels in Norfolk. Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, negotiated a peace with Aske. Howard was forced to promise that he would pardon the rebels and hold a parliament in York to discuss their demands. The rebels were convinced that this parliament would reopen the monasteries and therefore went back to their homes. (12)

However, as soon as the rebel army had dispersed. Henry ordered the arrest of the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace. About 200 people were executed for their part in the rebellion. This included Robert Aske and Lady Margaret Bulmer, who were burnt at the stake. Abbots of the four largest monasteries in the north were also executed. Gardiner accepted these decisions but suggested that Henry followed a new policy of making concessions to his subjects. Henry's response was furious. He accused Gardiner of returning to his old opinions, and complained that a faction was seeking to win him back to their "naughty" views. (13)

Stephen Gardiner - Leader of the Conservative Faction

On 10th June, 1540, Henry VIII ordered the arrest of Thomas Cromwell following the fiasco of his marriage to Anne of Cleves. Cromwell was executed and Henry recalled Stephen Gardiner as he needed his expertise in canon law to annul the marriage to Anne so he could marry Catherine Howard. As soon as he obtained power he arranged for his old enemy, the protestant reformer, Robert Barnes, to be burnt at the stake. As Antonia Fraser has pointed out the fall of Cromwell had allowed Gardiner his "opportunity to triumph politically and religiously" over the rival "reforming" faction. (14)

Gardiner replaced Thomas Cromwell as chancellor of the University of Cambridge. In the next few years Gardiner established a reputation for himself at home and abroad as a defender of orthodoxy against the Reformation. (15) In May 1543, Gardiner managed to persuade Henry to force Parliament to pass the Act for the Advancement of the True Religion. This act declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. It stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". (16)

Anne Askew & Catherine Parr

As Alison Weir has pointed out: "Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects." (17) In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested. This included Anne Askew.

Gardiner selected Askew because he believed she was associated with Henry's six wife, Catherine Parr, who he discovered had ignored this legislation "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature". Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack.

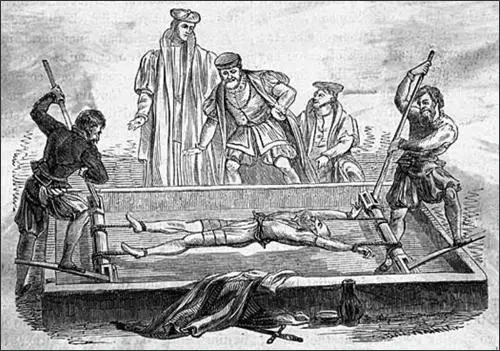

Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." (18) Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. (19)

Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. (20) It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. (21) Anne Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. (22)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII and raised concerns about Catherine's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible. (23)

David Loades has explained that "the greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions". However, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. "A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy." (24)

Catherine told Henry that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." (25) Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." (26) Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. (27)

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. (28). However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women." (29)

The Reign of Edward VI

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. In his will signed on 30th December 1546, Gardiner's name omitted from the list of executors and councillors. Edward was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist him in governing his new realm. His uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. He was now arguably the most influential person in the land. (30) Somerset was a radical Protestant and Gardiner was now out of power.

In May 1547 Gardiner wrote to the Duke of Somerset complaining about incidents of image-breaking and the circulation of protestant books. Gardiner urged Somerset to resist religious innovation during the royal minority. Somerset replied accusing Gardiner of scaremongering and warning him about his future behaviour. According to his biographer, C. D. C. Armstrong: "Gardiner had tried to counter religious innovation with four arguments: first, he warned of the inadvisability of change during a royal minority; second, he argued that innovation was contrary to Henry's express wishes; third, he raised technical and legal objections; and finally he offered theological objections." (31)

On 25th September 1547 Gardiner was summoned to appear before the Privy Council. Unhappy with his answers he was sent to Fleet Prison. Gardiner himself believed that he had been imprisoned in order to keep him away from the parliament that proceeded to repeal the Henrician religious legislation such as Act for the Advancement of the True Religion. He was released in January 1548, after the closure of parliament. (32)

On his release Gardiner returned to his diocese. He was unhappy when two committed protestants, Roger Tonge and Giles Ayre, arrived to take up canonries at Winchester Cathedral. They were soon complaining that Gardiner prevented them from preaching. Gardiner was once more brought before the council in May to answer their charges. "He was required to prove his good faith by preaching a sermon endorsing the regime's religious policy, and specifically covering papal authority, the dissolution of the monasteries, the suppression of shrines and images, the prohibition of various ceremonies, and the lawfulness of religious change notwithstanding the king's minority." (33)

Gardiner refused to do this and after preaching a sermon on 29th June, where he censured preachers who spoke against the mass, and upheld clerical celibacy. Gardiner was arrested and sent to the Tower of London. The government remained keen to secure Gardiner's conformity. In June 1549 he was brought a copy of the new prayer book and warned of the dangers of defying the Act of Uniformity. A high-level delegation visited him in June 1550 to demand a clear answer about the prayer book. He was persuaded to say that he could use the new liturgy himself, and allow its use in his diocese, but he declined to give anything in writing. On 14th February 1551, Gardiner was deprived of the see of Winchester. (34)

The Reign of Mary I

Gardiner's long imprisonment came to an end with Mary Tudor entered London on 3rd August 1553. Two weeks later Mary appointed Gardiner as her Lord Chancellor. (35) About the same time he was restored to the see of Winchester. Over the next two years Gardiner attempted to restore Catholicism in England. In the first Parliament held after Mary gained power most of the religious legislation of Edward's reign was repealed. However, he disagreed with those who advised Queen Mary to marry Philip of Spain. Gardiner thought Mary should marry Edward Courtenay, who he thought was more acceptable to the English people.

Gardiner's power was undermined by the rising led by Thomas Wyatt in January 1554. Gardiner was blamed for the rebellion because of his enthusiasm for reversing religious change. He was not helped by the involvement of his protégé Courtenay in the Wyatt affair, which he tried to cover up as best he could. (36) Gardiner had a growing number of critics in the government and his views on her marriage to Philip lost him the support of Queen Mary. However, he later accepted her decision and it was reported that Gardiner had had a genealogical tree drawn up to demonstrate Philip's descent from John of Gaunt. (37)

Stephen Gardiner advocated the arrest and execution of Princess Elizabeth. She was arrested and sent to the Tower of London on 18th March, 1554. (38) According to Simon Renard, the Spanish Ambassador in London, Gardiner wanted her declared a bastard (and thus excluded from the succession). (39) Whereas John Foxe claimed that Gardiner and other councillors sent a writ to the Tower ordering Elizabeth's execution, and that this was frustrated by the lieutenant of the Tower's decision to consult the queen before taking any action. (40)

In early 1555 Gardiner took part in the trials and examinations of John Hooper, Rowland Taylor, John Rogers, and Robert Ferrar, all of whom were burnt. He was also present in the summer of 1555 at meetings of the privy council which approved the execution of heretics. David Loades claims that "the threat of fire would send all these rats scurrying for cover, and when his bluff was called, he was taken aback." (41) During this period around 280 people were burnt at the stake. This compare to only 81 heretics executed during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547).

Stephen Gardiner died on 12th November, 1555.

Primary Sources

(1) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

The third session of the Reformation Parliament opened in January 1532 and the Commons immediately reverted to the question of clerical abuses. The outcome of their debates was a list of grievances, which Cromwell may have helped draw up, called the Supplication against the Ordinaries (i.e. the judges in ecclesiastical courts; usually the bishops or their deputies). This called in question the right of the Church to make laws of its own, and Henry therefore passed it to Convocation to consider. The bishops were in no mood to welcome such a document, for they were at last engaged in putting their house in order. New canons were being drafted, dealing with non-residency, simony and other abuses, and the Church leaders clearly envisaged a sweeping programme of reform, carried out under their aegis, which would be abruptly halted if their legislative power was called in question. Warham had already made his attitude plain by formally dissociating himself from any parliamentary statutes that derogated from the authority of the Pope or the liberties of the Church, and it was with his encouragement that Stephen Gardiner drew up a reply to the Supplication affirming that the Church's right to make its own laws was "grounded upon the Scripture of God and determination of Holy Church, which must also be a rule and square to try the justice of all laws, as well spiritual as temporal".

Gardiner was known to be in the King's favour and had only recently been made Bishop of Winchester. He would hardly have committed himself to such an uncompromising defence of the Church's position unless he had assumed that Henry would approve of it. After all, Henry had protected the Church against the anger of the Commons at the time of the Hunne and Standish affairs, and there was no reason to assume that he would act differently on this occasion. However, Gardiner and his fellow bishops had miscalculated, for by putting so much emphasis upon their independence and autonomy they appeared to be calling in question the King's "imperial" authority, to which he was now so deeply attached.

(2) Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007)

The spring of 1540 saw the surrender of the abbeys of Canterbury, Christchurch, Rochester and Waltham. With this closure, the dissolution of the monasteries was complete. Henry was now wearing on his thumb the great ruby that had, since the twelfth century, adorned the shrine of Becket at Canterbury. On his orders, the saint's body had been exhumed and thrown on a dung heap, because Becket had been a traitor to his King. Not all the monastic wealth found its way into the royal coffers in the Tower. Vast tracts of abbey land were bestowed upon noblemen loyal to the crown: Woburn Abbey was given to Sir John Russell, Wilton Abbey to Lord Herbert, and so on. Many stately homes surviving today are built on the sites of monastic establishments, sometimes with stones from the abbeys themselves. This redistribution of land from church to lay ownership served the purpose of binding the aristocracy by even greater ties of loyalty and gratitude to the King: they were hardly likely to oppose radical religious reforms when they had benefited so lavishly as a result of them.

(3) David Loades, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007)

Throughout his reign Henry had periodically displayed a compulsive need to demonstrate that he was in charge, and his brinkmanship over Cranmer's arrest may have been another example of that unlovable trait. If so, then the conservative position may have been less damaged by the debacle than appeared. In 1545 a Yorkshire gentlewoman named Anne Askew was arrested on suspicion of being a sacramentary. Her views were extreme, and pugnaciously expressed, so she would probably have ended at the stake in any case but her status gave her a particular value to the orthodox. This was greatly enhanced in the following year by the arrest of Dr Edward Crome, who, under interrogation, implicated a number of other people, both at court and in the City of London. Anne had been part of the same network, and she was now tortured for the purpose of establishing her links with the circle about the Queen, particularly Lady Denny and the Countess of Hertford. She died without revealing much of consequence, beyond the fact that she was personally known to a number of Catherine's companions, who had expressed sympathy for her plight. The Queen meanwhile continued to discuss theology, piety and the right use the bible, both with her friends and also with her husband. This was a practice, which she had established in the early days of their marriage, and Henry had always allowed her a great deal of latitude, tolerating from her, it was said, opinions which no one else dared to utter. In taking advantage of this indulgence to urge further measures of reform, she presented her enemies with an opening. Irritated by her performance on one occasion, the King complained to Gardiner about the unseemliness of being lectured by his wife. This was a heaven-sent opportunity, and undeterred by his previous failures, the bishop hastened to agree, adding that, if the King would give him permission he would produce such evidence that, "his majesty would easily perceive how perilous a matter it is to cherish a serpent within his own bosom". Henry gave his consent, as he had done to the arrest of Cranmer, articles were produced and a plan was drawn up for Catherine's arrest, the search of her chambers, and the laying of charges against at least three of her privy chamber.

The greatest secrecy was observed, and the unsuspecting Queen continued with her evangelical sessions. Henry even signed the articles against her. Then, however, the whole plot was leaked in mysterious circumstances. A copy of the articles, with the King's signature on it, was accidentally dropped by a member of the council, where it was found and brought to Catherine, who promptly collapsed. The King sent one of his physicians, a Dr Wendy, to attend upon her, and Wendy, who seems to have been in the secret, advised her to throw herself upon Henry's mercy. No doubt Anne Boleyn or Catherine Howard would have been grateful for a similar opportunity, but this was a different story. Seeking out her husband, the Queen humbly submitted herself, "... to your majesty's wisdom,, as my only anchor". She had never pretended to instruct, but only to learn, and had spoken to him of Godly things in order to ease and cheer his mind.

Henry, so that story goes, was completely disarmed, and a perfect reconciliation was affected, so that when Sir Thomas Wriothesley arrived at Whitehall the following day with an armed guard, he found all his suspects walking with the King in the garden, and was sent on his way with a fearsome ear-bending. Had the conservatives walked into another well-baited trap? As related by Foxe, the whole story has an air of melodramatic unreality about it, but it bears a striking resemblance to the two stories of Cranmer, which come from a different source. Whether Henry was playing games with his councillors in order to humiliate them, or with his wife in order to reassure himself of her submissiveness, or whether he was genuinely wavering between two courses of action, we shall probably never know. In outline the story is probably correct, and we may never be able to disentangle Foxe's embellishments. The consequences, in any case, were real enough. Gardiner finally lost the King's favour, and did not recover it, so that he was deliberately omitted from the regency council which Henry shortly after set up for his son's anticipated minority.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)