Anne Askew

Anne Askew, the second daughter of Sir William Askew (1489–1541) and his first wife, Elizabeth Wrottesley, was born in Stallingborough in 1521.

Her father, who was a landowner was knighted in 1513, and in 1521, at about the time of Anne's birth, he was appointed high sheriff of Lincolnshire. He also sat as MP for Grimsby in 1529. (1)

Askew received a good education from home tutors. When she was fifteen her family forced her to marry Thomas Kyme. Anne rebelled against her husband by refusing to adopt his surname. The couple also argued about religion. Anne was a supporter of Martin Luther, while her husband was a Catholic. (2)

From her reading of the Bible she believed that she had the right to divorce her husband. For example, she quoted St Paul: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? Askew was well connected. One of her brothers, Edward Askew, was cup-bearer to the king, and her half-brother Christopher, was gentleman of the privy chamber.

Anne Askew in London

Alison Plowden has argued that "Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them." (3)

In 1544 Askew decided to travel to London to meet Henry VIII and request a divorce from her husband. This was denied and documents show that a spy was assigned to keep a close watch on her behaviour. (4) She made contact with Joan Bocher, a leading figure in the Anabaptists. One spy who had lodgings opposite her own reported that "at midnight she beginneth to pray, and ceaseth not in many hours after." (5) Another contact was John Lascelles, who had previously worked for Thomas Cromwell, and was involved in the downfall of Catherine Howard. (6)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In March 1545 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy. She was questioned about a book she was carrying that had been written by John Frith, a Protestant priest who had been burnt for heresy in 1533, for claiming that neither purgatory nor transubstantiation could be proven by Holy Scriptures. She was interviewed by Edmund Bonner, the Bishop of London who had obtained the nickname of "Bloody Bonner" because of his ruthless persecution of heretics. (7)

After a great deal of debate Anne Askew was persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. With the help of her friend, Edward Hall, the Under-Sheriff of London, she was released after twelve days in prison. Askew's biographer, Diane Watt, argues: "It would appear that at this stage Bonner was concerned more about the heterodoxy of Askew's beliefs than with her connections and contacts, and that he principally wanted to rid himself of a woman whom he found obstinate and vexatious. Her treatment during her first examination suggests, therefore, that Askew's opponents did not yet view her as particularly influential or important." (8) Askew was released and sent back to her husband. However, when she arrived back to Lincolnshire she went to live with her brother, Sir Francis Askew.

Catherine Parr

In February 1546 conservatives in the Church of England, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, began plotting to destroy the radical Protestants. (9) He gained the support of Henry VIII. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects." (10) In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested. This included Anne Askew.

Gardiner selected Askew because he believed she was associated with Henry's sixth wife, Catherine Parr. (11) Catherine also criticised legislation that had been passed in May 1543 that had declared that the "lower sort" did not benefit from studying the Bible in English. The Act for the Advancement of the True Religion stated that "no women nor artificers, journeymen, serving men of the degree of yeomen or under husbandmen nor labourers" could in future read the Bible "privately or openly". Later, a clause was added that did allow any noble or gentlewoman to read the Bible, this activity must take place "to themselves alone and not to others". Catherine ignored this "by holding study among her ladies for the scriptures and listening to sermons of an evangelical nature". (12)

Gardiner believed the Queen was deliberately undermining the stability of the state. Gardiner tried his charm on Askew, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". On 28th June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy." (13)

Anne Askew - Tortured and Executed

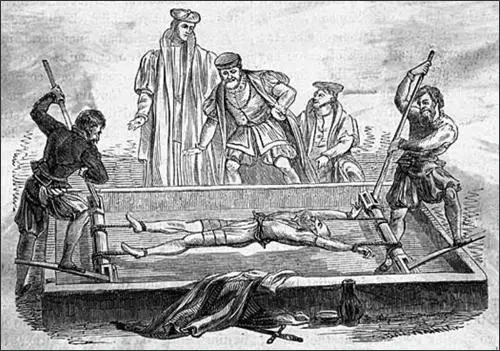

Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and his assistant, Richard Rich took over operating the rack. Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: "Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith." (14) Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. (15)

Askew was removed to a private house to recover and once more offered the opportunity to recant. When she refused she was taken to Newgate Prison to await her execution. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. (16) It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. (17)

Anne Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. (18) Also executed at the same time was John Lascelles, John Hadlam and John Hemley. (19) John Bale wrote that “Credibly am I informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, and abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements both declared wherein the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents." (20)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner had a meeting with Henry VIII after the execution of Anne Askew and raised concerns about his wife's religious beliefs. Henry, who was in great pain with his ulcerated leg and at first he was not interested in Gardiner's complaints. However, eventually Gardiner got Henry's agreement to arrest Catherine Parr and her three leading ladies-in-waiting, "Herbert, Lane and Tyrwhit" who had been involved in reading and discussing the Bible. (21)

Henry then went to see Catherine to discuss the subject of religion. Probably, aware what was happening, she replied that "in this, and all other cases, to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, Supreme Head and Governor here in earth, next under God". He reminded her that in the past she had discussed these matters. "Catherine had an answer for that too. She had disputed with Henry in religion, she said, principally to divert his mind from the pain of his leg but also to profit from her husband's own excellent learning as displayed in his replies." (22) Henry replied: "Is it even so, sweetheart? And tended your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore." (23) Gilbert Burnett has argued that Henry put up with Catherine's radical views on religion because of the good care she took of him as his nurse. (24)

The next day Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley arrived with a detachment of soldiers to arrest Catherine. Henry told him he had changed his mind and sent the men away. Glyn Redworth, the author of In Defence of the Church Catholic: The Life of Stephen Gardiner (1990) has disputed this story because it relies too much on the evidence of John Foxe, a leading Protestant at the time. (25) However, David Starkey, the author of Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII (2003) has argued that some historians "have been impressed by the wealth of accurate circumstantial detail, including, in particular, the names of Catherine's women." (26)

Primary Sources

(1) Jasper Ridley, Henry VIII (1984)

Anne Askew, this brave, cool, and very intelligent young gentlewoman... the daughter of Sir William Askew of Lincolnshire, had married Master Kyme, a Lincolnshire gentleman; but he had strongly objected to the Protestant doctrines which she advocated, and turned her out of his house. She came to London, and distributed illegal Protestant books. She had contacts at court with some of the most eminent ladies there - some said with the Queen herself. In March 1545 she was arrested, and examined by Bonner; but he was impressed by her intelligence and good manners, and he and other officials made it easy for her to recant.

(2) Antonia Fraser, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992)

Anne Askew was a young woman in her early twenties, of strongly reformist views - with a love of biblical... Undeniably she had many connections to the court. Anne Askew's sister was married to her steward of the late Duke of Suffolk; her brother Edward had a post in the King's household. She had been briefly married in her native Lincolnshire and borne children, but had come to London after her husband apparently expelled her for crossing swords with local priests. (One of the accusations against her was that she had abandoned her married name - Kyme - for her maiden name of Askew.)

(3) Alison Plowden, Tudor Women (2002)

Gardiner and his ally on the Council, the Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley, planned to attack the Queen through her ladies and believed they possessed a valuable weapon in the person of Anne Kyme, better known by her maiden name of Anne Askew, a notorious heretic already convicted and condemned. Anne, a truculent and argumentative young woman who came from a well-known Lincolnshire family, had left her husband and come to London to seek a divorce. Quoting fluently from the Scriptures, she claimed that her marriage was to longer valid in the sight of God, for had not St Paul written: "If a faithful woman have an unbelieving husband, which will not tarry with her she may leave him"? (Thomas Kyme was an old-fashioned Catholic who objected strongly to his wife's Bible-punching propensities.)

Anne failed to get her divorce, but her zeal, her sharp tongue and her lively wit soon made her a well; known figure in Protestant circles. Inevitably she soon came up against the law, and In March 1545 she was arrested on suspicion of heresy, specifically on a charge of denying the Real Presence in the sacrament of the altar. Pressed by Bishop Bonner on this vital point, Anne hesitated and was finally persuaded to sign a confession which amounted to an only slightly qualified statement of orthodox belief. A few days later she was released from gaol and went home to Lincolnshire - not to her husband but to her brother Sir Francis Askew.

Throughout that spring the conservative counter-attack gathered momentum, and by early summer a vigorous anti-heresy drive was in progress. At the end of May Thomas Kyme and his wife were summoned to appear before the Council. Although not proved, it's probable that the initiative for this move came from Kyme himself. Anne had refused to obey the order of the Court of Chancery to return to him, nor is it likely that he wanted her back. At the same time, he was in an invidious position, deserted-and defied by his wife and unable to marry again. It cannot have failed to occur to him that only Anne's death would finally solve his problems. Armed with a royal warrant and backed up by the Bishop of Lincoln (who had a long score to settle with Anne), Thomas Kyme forcibly removed her from her brother's protection and carried her off to London.

The Council's summons was ostensibly about the matrimonial issue, and Kyme was soon dismissed, but Anne, "for that she was very obstinate and heady in reasoning of matters of religion, wherein she avowed herself to be of a naughty opinion", was committed to Newgate prison to face renewed heresy charges. All through the following week determined efforts were made to wring from her a second and more complete recantation. The bishops were not anxious to make martyrs - retractions, especially from the better-known Protestants, would obviously be more valuable for propaganda purposes - but Anne was not to be caught a second time. When Stephen Gardiner tried his charm on her, begging her to believe he was her friend, concerned only with her soul's health, she retorted that that was just the attitude adopted by Judas "when he unfriendly betrayed Christ". Any lingering doubts and fears had passed. She knew now, with serene certainty, what Christ wanted from her, and she was ready to give it. At her trial on 28 June she flatly rejected the existence of any priestly miracle in the eucharist. "As for that ye call your God, it is a piece of bread. For a more proof thereof... let it but lie in the box three months and it will be mouldy." After that, there could be no question of the verdict, and sentence of death by burning was duly passed on this self-confessed and obstinate heretic.

Anne Askew is an interesting example often educated, highly intelligent, passionate woman destined to become the victim of the society in which she lived - a woman who could not accept her circumstances but fought an angry, hopeless battle against them. She was unquestionably sincere in her religious convictions - to what extent she also used them unconsciously to sublimate tensions and frustrations which might otherwise have been unbearable, we can only speculate. To Thomas Wriothesley the interesting thing about her was the fact that she was known to have close connections with the Court. Two of her brothers were in the royal service, and she was friendly with John Lassells - the same who had betrayed Katherine Howard five years before. It's highly probable that Anne had attended some of the Biblical study sessions in the Queen's apartments, and she was certainly acquainted with some of the Queen's ladies. If it could now be shown that any of these ladies - perhaps even the Queen herself had been in touch with her since her recent arrest; if it could be proved that they had been encouraging her to stand firm in her heresy, then the Lord Chancellor would have ample excuse for an attack on Catherine Parr.

Anne was therefore transferred to the Tower, where she received a visit from Wriothesley and his henchman Sir Richard Rich, the Solicitor General, but the interview proved a disappointment. She denied having received any visits while she had been in prison, and no one had willed her to stick to her opinions. Her maid had been given ten shillings by a man in a blue coat who said that Lady Hertford had sent it, and eight shillings by another man in a violet coat who said it came from Lady Denny, but whether this was true or not she didn't know, it was only what her maid had told her.

Convinced that Anne could have given them a long list of highly-placed secret sympathizers, and infuriated perhaps by her air of stubborn righteousness, Wriothesley ordered her to be stretched on the rack. This was not only illegal without a proper authorization from the Privy Council, it was unheard of to apply torture to a woman, let alone a gentlewoman like Anne Askew with friends in the outside world, and the Lieutenant ant of the Tower hastily dissociated himself from the whole proceeding. As a result, there followed a quite unprecedented scene, with the Lord Chancellor of England stripping off his gown and personally turning the handle of the rack. It was a foolish thing to do. Anne told him nothing more, if indeed there was anything to tell, and, since the story of her constancy soon got about, he'd only succeeded in turning her into a popular heroine.

The plot against the Queen fizzled out, largely due to the King's intervention. He took care that Katherine should receive advance warning of what was being planned for her and gave her the opportunity to explain that of course she had never for one moment intended to lay down the law to him, her lord and master, her only anchor, supreme head and governor here on earth. It was preposterous - against the ordinance of nature - for any woman to presume to teach her husband; it was she who must be taught by him. As for herself, if she had ever seemed bold enough to argue, it had not been to maintain her own opinions but to encourage discussion so that he might `pass away the weariness of his present infirmity' and she might profit by hearing his learned discourse! Satisfied, the King embraced his wife, and an affecting reconciliation took place.

If any real evidence of treasonable heresy had been uncovered in the Queen's household - if Henry had seriously suspected that Catherine was connected with any group which planned to challenge his own mandate from Heaven-then this story might have ended differently. As it was, he'd apparently been sufficiently irritated to feel that it would do her no harm to be taught a lesson, to be given a fright and a sharp warning not to meddle in matters which were no concern of outsiders, however privileged. Katherine, with her usual good sense, took the warning to heart, and there's no mention of any further theological disputations, even amicable ones, between husband and wife.

The Queen was unable to save Anne Askew, but her martyrdom on 16 July 1546 marked the end of the conservative resurgence, and by the time of the old King's death in the following January the progressive party was once more taking the lead.

(4) Peter Ackroyd, Tudors (2012)

On 15 July she was brought to Smithfield for burning, but she had been so broken by the rack that she could not stand. She was tied to the stake, and the faggots were lit. Rain and thunder marked these proceedings, whereupon one spectator called out 'A vengeance on you all that thus doth burn Christ's member'. At which remark a Catholic carter struck him down. The differences of faith among the people were clear enough.

(5) Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007)

Lord Chancellor Wriothesley was in charge of the interrogation, and he saw this chance as another to incriminate the Queen. When Anne Askew proved obdurate, he ordered her to be put on the rack, and, with Sir Richard Rich, personally conducted the examination. Anne Askew later dictated an account of the proceedings, in which she testified to being questioned as to whether she knew anything about the beliefs of the ladies of the Queen's household. She replied that she knew nothing. It was put to her that she had received gifts from these ladies, but she denied it. For her obstinacy, she was racked for a long time, but bravely refused to cry out, and when she swooned with the pain, the Lord Chancellor himself brought her round, and with his own hands turned the wheels of the machine, Rich assisting. Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. All in vain. Anne refused to deny her Protestant faith, and would not or could not implicate anyone near the Queen. On 18th June, she was arraigned at the Guildhall in London, and sentenced to death. She was burned at the stake on 16th July at Smithfield, along with John Lascelles, another Protestant, he who had first alerted Cranmer to Catherine Howard's pre-marital activities. Anne died bravely and quickly: the bag of gunpowder hung about her neck by a humane executioner to facilitate a quick end exploded almost immediately.

(6) Anne Askew, produced an account of her torture in the Tower of London and it was then smuggled out to her friends. (29th June, 1546)

Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith.

(7) John Foxe, Book of Martyrs (1563)

Hitherto we have treated of this good woman: now it remaineth that we touch somewhat as concerning her end and martyrdom. After that she (being born of such stock and kindred that she might have lived in great wealth and prosperity, if she would rather have followed the world than Christ) now had been so tormented, that she could neither live long in so great distress, neither yet by her adversaries be suffered to die in secret, the day of her execution being appointed, she was brought into Smithfield in a chair, because she could not go on her feet, by means of her great torments. When she was brought unto the stake, she was tied by the middle with a chain, that held up her body. When all things were thus prepared to the fire, Dr. Shaxton, who was then appointed to preach, began his sermon. Anne Askew, hearing and answering again unto him, where he said well, confirmed the same; where he said amiss, "There," said she, "he misseth, and speaketh without the book."

The sermon being finished, the martyrs, standing there tied at three several stakes ready to their martyrdom, began their prayers. The multitude and concourse of the people was exceeding; the place where they stood being railed about to keep out the press. Upon the bench under St. Bartholomew's church sat Wriothesley, chancellor of England; the old duke of Norfolk, the old earl of Bedford, the lord mayor, with divers others. Before the fire should be set unto them, one of the bench, hearing that they had gunpowder about them, and being alarmed lest the faggots, by strength of the gunpowder, would come flying about their ears, began to be afraid: but the earl of Bedford, declaring unto him how the gunpowder was not laid under the faggots, but only about their bodies, to rid them out of their pain, which having vent, there was no danger to them of the faggots, so diminished that fear.

Then Wriothesley, lord chancellor, sent to Anne Askew letters, offering to her the king's pardon if she would recant; who, refusing once to look upon them, made this answer again, that she came not thither to deny her Lord and Master. Then were the letters likewise offered unto the others, who, in like manner, following the constancy of the woman, denied not only to receive them, but also to look upon them. Whereupon the lord mayor, commanding fire to be put unto them, cried with a loud voice, Fiat justitia.

And thus the good Anne Askew, with these blessed martyrs, being troubled se many manner of ways, and having passed through so many torments, having now ended the long course of her agonies, being compassed in with flames of fire, as a blessed sacrifice unto God, she slept in the Lord A.D. 1546, leaving behind her a singular example of Christian constancy for all men to follow.

Student Activities

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)