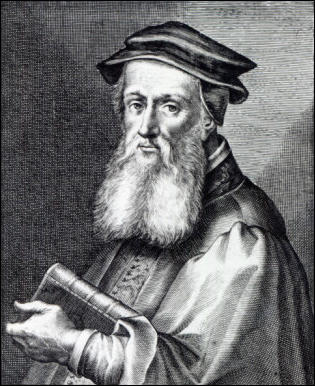

John Bale

John Bale, the son of Henry and Margaret Bale, was born near Dunwich in Suffolk, on 21st November 1495. He was educated at the Carmelite convent at Norwich and Jesus College. It seems that while at Cambridge University he did not join the reforming group led by people such as Hugh Latimer, Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, Nicholas Ridley, Miles Coverdale, Nicholas Shaxton, Matthew Parker, Robert Barnes and Thomas Bilney.

In 1530 he became prior of the white friars' convent in the port town of Maldon in Essex. In 1533 he was promoted to the Carmelite convent at Ipswich, and he had become prior at Doncaster. By this time he had began to show interest in the ideas of Martin Luther and in 1534 he was charged with heresy, but escaped conviction.

In 1536 he became a stipendiary priest at Thorndon in Suffolk. According to his biographer, John N. King, Bale's desire to marry was probably one reason for his leaving the Carmelites: "By 1536 he had renounced clerical vows, laid aside monastic attire, and married a woman named Dorothy. Virtually nothing is known about her besides her name, but she must have been a widow when Bale married her because she had a son of apprentice age... It may be that Bale's boyhood experience at a Carmelite convent shaped his views on clerical sexuality." (1)

John Bale - Church Historian

John Bale became a historian of the reform movement. For example, he recorded that Robert Barnes had a tremendous influence on Miles Coverdale. Bale later recalled: "Under the mastership of Robert Barnes he drank in good learning with a burning thirst. He was a young man of friendly and upright nature and very gentle spirit, and when the church of England revived, he was one of the first to make a pure profession of Christ … he gave himself wholly, to propagating the truth of Jesus Christ's gospel and manifesting his glory… The spirit of God … is in some a vehement wind, overturning mountains and rocks, but in him it is a still small voice comforting wavering hearts. His style is charming and gentle, flowing limpidly along: it moves and instructs and delights. (2)

In 1537 Bale was arrested for preaching heresy in a sermon that denounced "papistry". He was subsequently freed, thanks in part to the intercession of men who worked for Henry VIII. Bale's supporters included John Leland, a royal chaplain and Thomas Cromwell, the king's principal minister and vice-general for religious affairs. Bale later claimed that Cromwell had arranged his release from prison as a reward for his "polemical comedies". According to John N. King: "The minister supported a troupe of actors led by Bale, who staged allegorical morality plays which promoted protestant ideas and satirized Catholic beliefs by personifying the two sides as Virtues and Vices respectively." (3)

Bale became known for being a "Protestant playwright". His King John (1538) was based on a book written by William Tyndale, entitled The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528). This was Tyndale's most influential book outside his Bible translations. His biographer, David Daniell, argued: "Tyndale wrote to declare for the first time the two fundamental principles of the English reformers: the supreme authority of scripture in the church, and the supreme authority of the king in the state. Tyndale makes many pages of his book out of scripture, and he is scalding about the corruptions and superstitions in the church. His arguments are carefully developed, and his experiences of ordinary life are wide-ranging. Contrasted with the New Testament church and faith, he describes the sufferings of the people at the hands, especially, of monks and friars, though the whole intrusive hierarchy, as he sees it, from the pope down." (4)

The play was first staged at the home of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. The play flatters Henry VIII who is portrayed as the successor to "King John who attacks papal tyranny and completes England's schism from the Church of Rome. Despite assistance from Nobility, Clergy, and Civil Order, the medieval king's attempts at religious reform are blocked by a variety of stage Vices who include Usurped Power (as Pope Innocent III), Private Wealth (as Cardinal Pandulphus), Dissimulation (as Raymundus, a papal legate, and Simon, monk of Swinset), and Sedition (as Stephen Langton). Poisoned by Usurped Power, King John dies before he can complete the task of ecclesiastical reform. After John's death, the play moves triumphantly to Bale's own age when Imperial Majesty (a dramatic type for Henry VIII) defends ‘Christian faith’ and ‘the authority of God's holy word’ against continuing papal aggression." (5)

After the reformer's main enemy, Sir Thomas More, was executed on 6th July, 1535. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, were now the key political figures in England. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and had been burnt at the stake on 6th October, 1536. The edition they promoted, although mainly the work of Tyndale, had the name of Miles Coverdale on the cover. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England. (6)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September, 1538. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." (7) Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." (8)

The Six Articles

Reformers such as John Bale suffered a set-back in May 1539 when the bill of the Six Articles was presented by Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk in Parliament. It was soon clear that it had the support of Henry VIII. Although the word "transubstantiation" was not used, the real presence of Christ's very body and blood in the bread and wine was endorsed. So also was the idea of purgatory. The six articles presented a serious problem for Bale and other religious reformers. Bale had argued against transubstantiation and purgatory for many years. Bale now faced a choice between obeying the king as supreme head of the church and standing by the doctrine he had had a key role in developing and promoting for the past decade. (9)

Bishop Hugh Latimer and Bishop Nicholas Shaxton both spoke against the Six Articles in the House of Lords. Thomas Cromwell was unable to come to their aid and in July they were both forced to resign their bishoprics. For a time it was thought that Henry would order their execution as heretics. He eventually decided against this measure and instead they were ordered to retire from preaching. John Bale shared his friend's views but kept his thoughts to himself. Robert Barnes, who opposed the Six Articles, was burnt at the stake on 30th July, 1540. (10)

Cromwell retaliated by arresting Richard Sampson, Bishop of Chichester and Nicholas Wotton, staunch conservatives in religious matters. He then began negotiating the release of Barnes. However, this was unsuccessful and it was now clear that Cromwell was in serious danger. The French ambassador reported on 10th April, 1540, that Cromwell was "tottering" and began speculating about who would succeed to his offices. (11)

Quarrels in the Privy Council continued and Charles de Marillac reported to François I on 1st June, 1540, that "things are brought to such a pass that either Cromwell's party or that of the Bishop of Winchester must succumb". On 10th June, Cromwell arrived slightly late for a meeting of the Privy Council. Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, shouted out, "Cromwell! Do not sit there! That is no place for you! Traitors do not sit among gentlemen." The captain of the guard came forward and arrested him. Cromwell was charged with treason and heresy. Norfolk went over and ripped the chains of authority from his neck, "relishing the opportunity to restore this low-born man to his former status". Cromwell was led out through a side door which opened down onto the river and taken by boat the short journey from Westminster to the Tower of London. (12)

John Bale lost his main protector, Thomas Cromwell, when he was executed for treason on 28th July, 1540. Bale was unable to intervene when Henry VIII began burning Protestants for heresy. He later reported on the execution of Anne Askew. On 16th July 1546, Agnew "still horribly crippled by her tortures" was carried to execution in Smithfield in a chair as she could not walk and every movement caused her severe pain. (13) It was reported that she was taken to the stake which had a small seat attached to it, on which she sat astride. Chains were used to bind her body firmly to the stake at the ankles, knees, waist, chest and neck. (14)

Anne Askew's executioner helped her die quickly by hanging a bag of gunpowder around her neck. (15) Also executed at the same time was John Lascelles, John Hadlam and John Hemley. (16) John Bale wrote that “Credibly am I informed by various Dutch merchants who were present there, that in the time of their sufferings, the sky, and abhorring so wicked an act, suddenly altered colour, and the clouds from above gave a thunder clap, not unlike the one written in Psalm 76. The elements both declared wherein the high displeasure of God for so tyrannous a murder of innocents." (17)

Bale decided it was too dangerous in England and went to live in Germany. He published several books on church history, the most important being The Image of Both Churches (1545), which provided the first complete commentary on the book of Revelation to be printed in English. "This work views Christian history as a continuing struggle between the ‘true’ church, based on Jesus's teachings in the gospels, and the ‘false’ Church of Rome, whose leadership by the pope results from its subversion by Antichrist and the misinterpretation of scriptural texts." (18)

Jasper Ridley has described Bale during this period as a "ferocious anti-Catholic pamphleteer". John N. King has pointed out: "These works, with many others like them, generally denounce the papacy, the ritualism of the Roman liturgy, belief in transubstantiation and the mass, the veneration of saints, and the cult of the Virgin Mary. In their place Bale advocates protestant practices designed to nurture individual faith: gospel preaching, lay education in the vernacular Bible, and a service of holy communion that commemorates Christ's sacrifice rather than re-enacting it." (19)

Reign of Edward VI

Henry VIII died on 28th January 1547. Edward VI was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist his son in governing his new realm. It was not long before his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. He was sympathetic to the religious ideas of people like John Bale and he ordered the release from prison of reformers such as Bishop Hugh Latimer. (20)

This gave the opportunity for John Bale and his friends such as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Nicholas Ridley, their long-awaited opportunity to implement the doctrinal changes they had desired. Later that year the Six Articles were repealed. Bale returned to England and was later appointed as Bishop of Ossory in Ireland. (21)

Edmund Bonner, a former persecutor of the heretics, lost his post as Bishop of London. He was now replaced in the post by Nicholas Ridley in February 1550. (22) Among his earliest acts was to order the destruction of altars, to "turn the simple from the old superstitious opinions of the popish mass", and their replacement with "honest" tables that would help to instill "the right use of the Lord's supper" as a godly meal. By the end of the year every church in the city but one had a communion table. He examined every incumbent and curate for his learning, and threatened to "eject" those who failed to come up to the standards he required. (23)

Reign of Mary Tudor

King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. Queen Mary now ordered the arrests of the leading Protestants in England. This included Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, Bishop Hugh Latimer, Bishop Nicholas Ridley and Bishop John Bradford. To their mutual comfort, they "did read over the new testament with great deliberation and painful study", discussing again the meaning of Christ's sacrifice, and reinforcing their opinions on the spiritual presence in the Lord's supper. (24) Eventually all four men were burnt at the stake.

John Bale once again went into exile where he launched a vigorous attack on the religious policies of Mary. During her forty-five months in power she ordered the burning alive of 227 men and 56 women for their Protestant beliefs. Bale argued that several recent examples of monstrous births, like the Siamese twins in Oxfordshire and the child born without legs or arms in Coventry to prove that God was displeased with the actions of Mary. (25)

Following the accession of Queen Elizabeth, Bale returned to England, and on 10th January 1560 was appointed by the crown as canon of the eleventh prebend in Canterbury Cathedral. Now aged 65, Bale was not in good health and he wrote nothing of great significance toward the end of his life. (26)

John Bale died on 26th November, 1563.

Primary Sources

(1) John N. King, John Bale : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Bale's writings are indeed notable for a consistent historiographical vision which is expressed most fully in his Image of both Churches, but is also vital to the polemical plays, propaganda tracts, and works of scholarship written from the 1530s onwards. Above all, his interpretation of Revelation affords an apocalyptic paradigm for virtually everything that he wrote. In his eyes, a proper understanding of Revelation should enable believers to trace the historical trajectory of the conflict between ‘true’ and ‘false’ churches through the seven ages prophesied by the blowing of seven trumpets, the opening of the seven seals, and the pouring of the seven vials. These ages proceed from an initial period of apostolic purity to the sixth age, which encompasses the persecution of the faithful from the time of John Wyclif until Bale's own lifetime. Wyclif and William Tyndale are leading representatives of the ‘true’ religion which had been brought directly to England by Joseph of Arimathea, one which remained uncorrupted by fraudulent apostolic succession of Roman pontiffs who act as agents of Antichrist. Present history looks forward to the final age, when the world as it is known will come to an end.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)