Pilgrimage of Grace

In 1535 Henry VIII began to close the monasteries in England. Most people living in the North of England were still strong supporters of the Catholic faith. Geoffrey Moorhouse, the author of The Pilgrimage of Grace (2002), has pointed out, that these people were more opposed to this policy. "The monasteries as a whole might spend no more than five per cent of their income on charity, but in the North they were a great deal more generous, doubtless because the need was greater in an area where poverty was more widespread and very real. There, they still did much to relieve the poor and the sick, they provided shelter for the traveller, and they meant the difference between a full belly and starvation to considerable numbers of tenants, even if they were sometimes imperfect landlords." (1)

The monasteries made a substantial contribution to the local economy. The Benedictines in Durham had for a long time operated coal mines in the region. The Cistercians had introduced commercial sheep farming in Yorkshire. Unemployment was increasing and if the monasteries were closed down, this would cause further problems as they employed local people to carry out most of the manual work needed. Those who worked the land were also worried about the changes that were taking place. The transfer of land from open field to enclosure and from arable to pasture also increased unemployment. (2)

Dissolution of the Monasteries

On 28th September 1536, the King's commissioners for the suppression of monasteries arrived to take possession of Hexham Abbey and eject the monks. They found the abbey gates locked and barricaded. "A monk appeared on the roof of the abbey, dressed in armour; he said that there were twenty brothers in the abbey armed with guns and cannon, who would all die before the commissioners should take it." The commissioners retired to Corbridge, and informed Thomas Cromwell of what had happened. (3)

The following month disturbances took place at the market town of Louth in Lincolnshire. The rebels captured local officials and demanded the arrest of leading Church figures they considered to be heretics. This included Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer. They wrote a letter to Henry VIII claiming that they had taken this action because they were suffering from "extreme poverty". (4)

Lord John Hussey was at his house at Sleaford on 2nd October 1536 when reports reached him about the disturbance at Louth. His immediate reaction was to organise against the rebels. He ordered the breaking down of bridges and opening of sluices to stop the passage of people into East Anglia. However, most of the people Hussey tried to reach either had fled or were under house arrest. "Hussey offered to ride to the king and plead for their pardon if they would submit, a suggestion which they refused. It was also reported that at this meeting Hussey refused to betray Henry by joining the rebels, but he also admitted that he was impotent to resist them because his tenants would not serve against them." (5)

Geoffrey Moorhouse has argued that "Hussey certainly behaved from the outset like someone who was not at all sure which side he proposed to back." However, he refused to join the king's army being assembled in Nottinghamshire. (6) Soon the whole of Lincolnshire was up in arms, but most members of "the gentry promptly asserted their control over the movement, which might otherwise have got dangerously out of hand". (7)

Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, and Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, were was sent to Lincolnshire to deal with the rebels. In a age before a standing army, loyal forces were not easy to raise. (8) "Appointed the king's lieutenant to suppress the Lincolnshire rebels, he advanced fast from Suffolk to Stamford, gathering troops as he went; but by the time he was ready to fight, the rebels had disbanded. On 16th October he entered Lincoln and began to pacify the rest of the county, investigate the origins of the rising, and prevent the southward spread of the pilgrimage." (9)

Robert Aske

A lawyer, Robert Aske, was travelling to London on 4th October when he was captured by a group of rebels involved in the uprising. (10) Aske agreed to use his talents as a lawyer to help the rebels. He wrote letters for them explaining their complaints. These letters insisted that their quarrel was not with the King or the nobility, but with the government of the realm, especially Thomas Cromwell. The historian, Geoffrey Moorhouse, has pointed out: "Robert Aske never wavered in his belief that a just and well-ordered society was based upon a due recognition of rank and privilege, starting with that of their anointed prince, Henry VIII." (11)

Aske now returned home and began to persuade people from Yorkshire to support the rebellion. People joined what became known as the Pilgrimage of Grace for a variety of different reasons. Derek Wilson, the author of A Tudor Tapestry: Men, Women & Society in Reformation England (1972) has argued: "It would be incorrect to view the rebellion in Yorkshire, the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, as purely and simply an upsurge of militant piety on behalf of the old religion. Unpopular taxes, local and regional grievances, poor harvests as well as the attack on the monasteries and the Reformation legislation all contributed to the creation of a tense atmosphere in many parts of the country". (12)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Within a few days, 40,000 men had risen in the East Riding and were marching on York. (13) Aske called on his men to take an oath to join "our Pilgrimage of Grace" for "the commonwealth... the maintenance of God's Faith and Church militant, preservation of the King's person and issue, and purifying of the nobility of all villein's blood and evil counsellors, to the restitution of Christ's Church and suppression of heretics' opinions". (14) Aske published a declaration obliging "every man to be true to the king's issue, and the noble blood, and preserve the Church of God from spoiling". (15)

By the end of the month the rising had engulfed virtually all the northern counties, roughly one-third of the country. (16) Scott Harrison has suggested that: "Twenty thousand men, women and children may have actively supported the rebellion at some stages, and many more may have taken the rebel oath before returning to their homes... If one accepts an estimate for the total population of the region of approximately seventy thousand in 1536, the fact that over one-third of the inhabitants were active rebels indicates a high level of involvement." (17)

On 6th October, Thomas Darcy wrote to Henry VIII giving details of the uprising in his area. He told the King he did not have enough soldiers to resist the rebels and he would have to retire to Pontefract Castle. "Henry wrote to Darcy that he was surprised that he could do nothing more effective against the rebels, but assured him that he had no doubts as to his loyalty. Privately, Henry told his counsellors that he suspected that Darcy was a traitor." (18) Darcy realized he was outnumbered and thought it better to pacify the rebels rather than take them on in battle. Another reason for his defeatist views, according to Geoffrey Moorhouse, was his poor health: "He was now sixty-nine years old, suffering from a rupture he had incurred in one of Henry's French adventures and from a chronic bowel disorder, which may be why his humour has been described as grim." (19)

A. L. Morton has suggested that all the evidence indicates: "The Pilgrimage of Grace... was a reactionary, Catholic movement of the North, led by the still half-feudal nobility of that area and aimed against the Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries. But if the leaders were nobles the mass character of the rising indicated a deep discontent and the rank and file were drawn in large measure from the dispossessed and from the threatened peasantry." (20)

On 11th October 1536, Robert Aske and his army arrived at Jervaulx Abbey. The abbot, Adam Sedbar, later recalled that the rebels wanted him to take the oath supporting the Pilgrimage of Grace. According to his biographer, Claire Cross: "With his own father and a boy, Sedbar fled to Witton Fell and remained there for four days. In his absence the rebels tried to persuade the convent to elect a new abbot, and in this extremity the monks prevailed upon him to return." (21)

At first Sedbar refused to take the oath but after being threatened with execution he agreed to join the rebellion. Geoffrey Moorhouse doubts this story and suggests that "Sedbar was in a much less supine mood than he admitted, confident enough of the popularity of this burgeoning cause". (22) Sedbar agreed that Aske's army could take control of the abbey's horses. He also travelled with them to Darlington where he spoke in favour of the rising.

Robert Aske and his rebels entered York on 16th October. It is estimated that Aske now led an army that numbered 20,000. (23) Aske made a speech where he pointed out "we have taken (this pilgrimage) for the preservation of Christ's church, of this realm of England, the King our sovereign lord, the nobility and commons of the same... the monasteries... in the north parts (they) gave great alms to poor men and laudably served God... and by occasion of the said suppression the divine in divine service of Almighty God is much diminished." (24)

Robert Aske arrived at Pontefract Castle on 20th October. After a short siege, Thomas Darcy, running short of supplies, surrendered the castle. Richard Hoyle has pointed out: "Darcy's actions are in fact perfectly plausible when taken at face value and especially when the Pilgrimage of Grace is seen as a widespread popular movement in opposition to expected and feared religious innovations. When disturbances broke out in Yorkshire, he sent the king a long and accurate assessment of the situation and sought reinforcements, money, supplies of munitions, and the authority to mobilize. On two further occasions he wrote at length describing a deteriorating situation. On all three occasions his information and advice were ignored... It was Aske's contention that Darcy could not have resisted a siege, but would have been killed if the commons had stormed the castle." (25)

Edward Lee, Archbishop of York, was sheltering in the castle. He had a reputation as a conservative and in the autumn of 1535 had written to Thomas Cromwell, complaining about the new radical preachers who were active in the region. He followed this up six months later with the suggestion that nobody should be allowed to preach unless they had been granted permission from Henry VIII. Lee had also complained about the plan to close Hexham Abbey. (26) Aske and his followers assumed that the archbishop sympathized with their aims for the restoration of the church's liberties and when he took the pilgrims' oath he was allowed to go free. (27)

After discussions with Aske, Thomas Darcy decided to join the Pilgrimage of Grace. He swore the oath presented to him by Aske. It included the following: "Ye shall not enter into this our Pilgrimage of Grace for the Commonwealth, but only for the love that ye do bear unto Almighty God, his faith, and to Holy Church militant and the maintenance thereof, to the preservation of the King's person and his issue, to the purifying of the nobility, and to expulse all villein blood and evil councillors against the commonwealth from his Grace and his Privy Council of the same. And ye shall not enter into our said Pilgrimage for no particular profit to your self, nor to do any displeasure to any private person, but by counsel of the commonwealth, nor slay nor murder for no envy, but in your hearts put away all fear and dread, and take afore you the Cross of Christ, and in your hearts His faith, the Restitution of the Church, the suppression of these Heretics and their opinions, by all the holy contents of this book." (28)

The oath made it clear that the rebels were loyal to Henry VIII and blamed the closing of the monasteries on the king's officials such as Vicar-General Thomas Cromwell, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, Bishop Hugh Latimer, Bishop Nicholas Ridley, Bishop Nicholas Shaxton, Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley and Solicitor-General Richard Rich. To followers of the Pilgrimage of Grace, these men were heretics and deserved to be burnt at the stake.

An attempt was made to persuade Henry Algernon Percy, 5th Earl of Northumberland, to join the Pilgrimage of Grace. His mother and brothers were sympathetic to the rebels. Percy told Henry that his health prevented him from taking military action against the rebellion. Robert Aske and his men came to Wressle Castle to try to gain his support. When he refused he was warned that his life was in danger. He replied that "he did not care, he should die but once. Let them strike off his head whereby they should rid him of much pain, ever saying he would be dead". (29)

Geoffrey Moorhouse, the author of The Pilgrimage of Grace (2002), claims: "Aske made one more attempt to win Percy over and was at last successful in obtaining some sort of agreement that he would do nothing to injure the Pilgrimage... Percy consented to move out of Wressle and leave it in Aske's hands. Before November was halfway through he had, in fact, formally and legally made over the castle to Aske for as long as the captain needed it; and thus it became the convenient base for the subsequent direction of the Pilgrimage." (30)

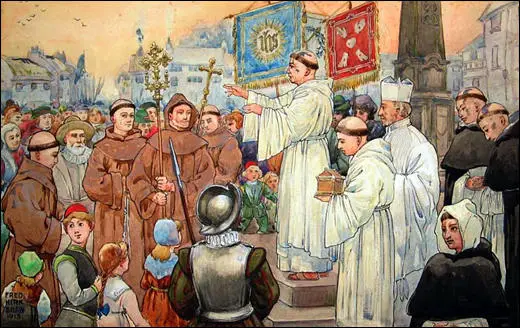

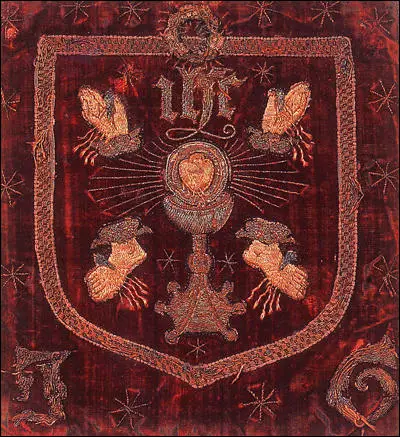

Robert Aske offered the leadership of the Pilgrimage of Grace to Thomas Darcy. He refused but agreed to provide soldiers for the cause. To show his commitment to the new allegiance, one of his first acts was to send the oath that he signed into Lancashire. He also arranged for flags to be made that included the religious insignia of the Five Wounds of Christ (it depicted a bleeding heart above a chalice, both being surrounded at the corners by the pierced hands and feet).

Sir Robert Constable, a veteran of the Flodden Field, was another significant member of the rebellion. It has been claimed by Christine M. Newman that he may have joined the Pilgrimage of Grace because of the influence of Henry Percy, 6th Earl of Northumberland. "Percy affinities undoubtedly played a part in the rebellion and this, to some extent, may have accounted for Constable's stance. Other factors, such as his increasing dissatisfaction with the aims of royal government, may also have played a part." (31)

Geoffrey Moorhouse believes that Constable's poor health (he had "perpetual gout") was a factor in his decision to join Robert Aske. Moorehouse argues that Constable and Thomas Darcy had made a strange decision: "In switching sides Constable, like Darcy, was putting himself under the command of a man half his age, from somewhere beneath him in the social scale and with no military experience whatsoever, whereas these two old sweats had spent long years of their lives fighting at home and abroad." (32)

The leadership of Robert Aske has been praised by historians. One of his requests was that Henry VIII should hold a meeting of Parliament in the north. Anthony Fletcher has argued: "Aske's intention throughout the campaign he directed was to overawe the government into granting the demands of the north, by presenting a show of force. Only one man was killed during the Pilgrimage. He did not want to advance south unless Henry refused the Pilgrims' petition and he had no plan to form an alternative government or remove the king. Aske merely wanted to give the north a say in the affairs of the nation, to remove Cromwell and reverse certain policies of the Henrician Reformation." (33)

By the end of October the rising had spread to Lancashire, Durham, Westmorland, Northumberland and Cumberland. The rebels arrived at Sawley Abbey, near Clitheroe, which had recently been closed down and the land leased to Sir Arthur Darcy. The man was evicted and the monks were invited to return. When he heard the news Henry instructed Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, to seize possession of the abbey, and hang the Abbot and the monks without trial. "They were to be hanged in their monks' habits, the Abbot and some of the chief monks on long pieces of timber protruding from the steeple, and the rest at suitable places in the surrounding villages. Derby explained to Henry that he did not have enough troops to carry out these orders in the face of the opposition of the whole countryside." (34)

Peace Talks with Henry VIII

Henry VIII summoned Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, out of retirement to deal with the Pilgrimage of Grace. Norfolk, although he was 63, was the country's best soldier. Norfolk was also the leading Roman Catholic and a strong opponent of Thomas Cromwell and it was hoped that he was a man who the rebels would trust. Norfolk was able to raise a large army but he had doubts about their reliability and suggested to the King that he should negotiate with the rebels. (35)

Thomas Darcy, Robert Constable and Francis Bigod took part in negotiations with the Duke of Norfolk. He tried to persuade them and the other Yorkshire nobles and gentlemen to regain the King's favour by handing over Robert Aske. However, they refused and Norfolk returned to London and suggested to Henry that the best strategy was to offer a pardon to all the northern rebels. When the rebel army had dispersed the King could arrange for its leaders to be punished. Henry eventually took this advice and on 7th December, 1536, he granted a pardon to everyone north of Doncaster who had taken part in the rebellion. Henry also invited Aske to London to discuss the grievances of the people of Yorkshire. (36)

Robert Aske spent the Christmas holiday with Henry at Greenwich Palace. When they first met Henry told Aske: "Be you welcome, my good Aske; it is my wish that here, before my council, you ask what you desire and I will grant it." Aske replied: "Sir, your majesty allows yourself to be governed by a tyrant named Cromwell. Everyone knows that if it had not been for him the 7,000 poor priests I have in my company would not be ruined wanderers as they are now." Henry gave the impression that he agreed with Aske about Thomas Cromwell and asked him to prepare a history of the previous few months. To show his support he gave him a jacket of crimson silk. (37)

Arrest & Execution of Robert Aske

Following the agreement to disband the rebel army in December 1536, Francis Bigod began to fear that Henry VIII would seek revenge on its leaders. Bigod accused Robert Aske and Thomas Darcy of betraying the Pilgrimage of Grace. On 15th January 1537, Bigod launched another revolt. He assembled his small army with a plan to attack Hull. Aske agreed to return to Yorkshire and assemble his men to defeat Bigod. He then joined up with Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his army made up of 4,000 men. Bigod was easily defeated and after being captured on 10th February, 1537, was imprisoned in Carlisle Castle. (38)

On 24th March, Robert Aske, Thomas Darcy and Robert Constable were asked by the Duke of Norfolk to return to London in order to have a meeting with Henry VIII. They were told that the King wanted to thank them for helping to put down the Bigod rebellion. On their arrival they were all arrested and sent to the Tower of London. (39)

Aske was charged with renewed conspiracy after the pardon. (40) Thomas Cromwell had kept a very low profile during the Pilgrimage of Grace but there is no reason to suppose that he lost his place as the king's right-hand man. (41) However, he now conducted the examination of Robert Aske on 11th May. Robert Aske was asked a total of 107 written questions. Geoffrey Moorhouse claims that Aske made no attempt to hide his early involvement in the Pilgrimage of Grace: "The most striking thing about all of Robert Aske's testimony is how very straightforward he was, especially for one in such a predicament as his. It was as though he was not only incapable of telling a lie but even of obfuscating the truth." (42)

When news reached John Bulmer and Margaret Cheyney in Lastingham of the arrest of Aske and Darcy, they discussed the possibility of Bulmer fleeing to Scotland. Their parish priest later recalled that if Bulmer left the country on his own she "feared that she should be parted from him forever". Apparently he stated "Pretty Peg, I will never forsake thee." According to Geoffrey Moorhouse: "Others heard him say that he would rather be put on the rack than be parted from his wife. For her part, she vowed that she would rather be torn to pieces than go to London, and she begged him to get a ship that would take them and their three-month-old son to the safety of Scotland." (43)

The government later claimed that Margaret suggested that John Bulmer should start another uprising. It was said "she enticed Sir John Bulmer to raise the commons again" and that "Margaret counselled him to flee the realm (if the commons would not rise) than that he and she should be parted". John Bulmer then contacted several local landowners to discuss his plans. At least two of the men approached, Thomas Francke and Gregory Conyers, told Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk about the planned uprising by Bulmer. (44)

John Bulmer and Margaret Cheyney were arrested in early April, 1537. They were taken to London and were tortured. "We have no record of Margaret's confession, either, though it was doubtless extracted, but Bulmer refused to say anything in his that would implicate her and he pleaded guilty to the treason charge, possibly in the forlorn hope that this would exonerate her. Both of them, in fact, originally pleaded not guilty before changing their minds while the jury was actually considering its verdict and one view is that they did so because they had been promised the King's mercy if they admitted their guilt. Bulmer referred to Cheyney as his wife and nothing else right up to the end, much to the irritation of his accusers and the judge." (45)

Thomas Darcy and John Hussey were tried in Westminster Hall. During his trial Darcy accused Thomas Cromwell of being responsible for the Pilgrimage of Grace: "Cromwell it is thou that art the very original and chief causer of this rebellion and mischief, and art likewise causer of the apprehension of us that be noble men and dost daily earnestly travail to bring us to our end and to strike off our heads." (46) The two men were also accused of having meetings with Eustace Chapuys in September 1534 and urged him to encourage King Charles V "to intervene in England" and place Henry's daughter, Mary, on the throne. (47)

Despite his spirited defence Darcy and Hussey were found guilty of treason on 15th May. Henry VIII wanted Darcy to be executed in Doncaster. However, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, told the King that as Darcy was a popular figure in the area this act might start another uprising. Henry was persuaded to have Darcy executed at Tower Hill instead. This was carried out on 30th June 1537 and Darcy's head was displayed on London Bridge. (48) Darcy's biographer, Richard Hoyle, has pointed out: "It was later claimed that Darcy had been found guilty only because Sir Thomas Cromwell, principal secretary, led the peers trying him and persuaded them to believe that he would be pardoned by the king." (49) Robert Constable was taken to Hull to be executed, whereas John Hussey was executed in Lincoln. (50)

Thomas Cromwell managed to obtain statements from some of the prisoners that implicated Robert Aske in the Sir Francis Bigod rebellion. Cromwell also found a letter signed by Aske and Darcy that called on people not to join Bigod but to remain in their homes. Cromwell argued that by urging them to stay in their homes, they were by implication telling them not to join the King's forces and not to assist in the suppression of the rising. This, according to Cromwell, this was treason.

Aske was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. Henry VIII insisted that the punishment should be carried out in York where the uprising began so that the local people could see what happens to traitors. Market day had been chosen for the execution. On 12th July, 1537, Aske was tied to a hurdle and dragged through the streets of the city. He was taken to the high upon the mound on which Clifford's Tower stood. On the scaffold Aske asked for forgiveness. Aske was hanged, almost to the point of death, revived, castrated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered (his body was chopped into four pieces). (51)

Margaret Cheyney was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. Madeleine Dodds and Ruth Dodds, the authors of The Pilgrimage of Grace (1915) have speculated on the reasons for this. They argued that she "committed no overt act of treason; her offences were merely words and silence". They believed that Henry VIII wanted to use the case of Cheyney as an example to others. "There can be no doubt that many women were ardent supporters of the Pilgrimage.... Lady Bulmer's execution... was an object-lesson to husbands... to teach them to distrust their wives." (52)

Sharon L. Jansen agrees with this point of view: "Margaret Cheyney's sexual power was suspect; women like her could lure their husbands into danger. Men needed to submit to their princes, and they also needed to control their wives, their mothers, their daughters, their female servants. Margaret Cheyney had violated the contemporary notion that wives should be chaste, silent, and obedient, and her death could certainly have been intended as a warning about the proper behaviour of women." (53)

The Aftermath

It is estimated that about 200 people were executed for their part in the Pilgrimage of Grace. This included Robert Aske, Thomas Darcy, Francis Bigod, Robert Constable, John Hussey, John Bulmer and Margaret Cheyney. The heads of two of the largest religious houses, Abbot William Thirsk of Fountains Abbey and Abbot Adam Sedbar of Jervaulx Abbey, were also put to death. (54) However, others like Edward Lee, the Archbishop of York, who had signed the oath, was spared.

As Jasper Ridley, the author of Henry VIII (1984) has pointed out: "Nearly all the noblemen and gentlemen of Yorkshire had joined the Pilgrimage of Grace in the autumn. Henry could not execute them all. He divided them, somewhat arbitrarily, into two groups - those who were to be forgiven and restored to office and favour, and those who were to be executed on framed-up charges of having committed fresh acts of rebellion after the general pardon. Archbishop Lee, Lord Scrope, Lord Latimer, Sir Robert Bowes, Sir Ralph Ellerker and Sir Marmaduke Constable continued to serve as Henry's loyal servants." (55)

Thomas Cromwell was determined to remove all those religious leaders who he suspected of being supporters of the Pilgrimage of Grace. In the winter of 1537 Cromwell sent out his commissioners to discover the loyalty of the people who were running the remaining monasteries. The commissioners relied heavily on information from local people. William Sherburne, a former friar, accused Robert Hobbes of being a supporter of the rebels. Hobbes was interviewed and he refused to recant: "Hobbes held firm, although in some places it is difficult to establish an exact meaning from the long and rambling depositions of a man physically ill from strangury, and to disentangle apologies for bluntness of speech from repentance on points of principle. It is certain, however, that to the very end he remained opposed to the suppression of the monasteries, the distribution of ‘wretched heretic books’ by Cromwell, and the royal divorce, all sufficient to make his conviction a formality. Indeed, he confessed his offences and offered no defence." Robert Hobbes was hanged, drawn, and quartered outside the abbey and its land and property was given to the Crown. (56)

Richard Whiting, the Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey survived this investigation. Cromwell sent his agents back the following year. This time they were more critical of Wilding's leadership. They identified divisions among the monks, especially between the older and younger ones, and that the abbot had his favourites in the community. Whiting was also accused of spending too much away from the monastery and living at his manors of Sturminster Newton in Dorset and Ashbury in Berkshire. (57)

On 19th September 1539, Richard Layton, Thomas Moyle, and Richard Pollard arrived at the abbey without warning. (58) They were not convinced about Whiting's answers and he was sent to the Tower of London. They discovered a book condemning Henry VIII's divorce from Catherine of Aragon. They also discovered evidence that Whiting hid a number of precious objects from Cromwell's agents. The commissioners wrote to Cromwell claiming that they had now come to the knowledge of "divers (many) and sundry treasons committed by the Abbot of Glastonbury". (59)

Whiting was sent back to Somerset in the care of Richard Pollard and reached Wells on 14 November. "Here some sort of trial apparently took place, and next day, Saturday, 15th November, he was taken to Glastonbury with two of his monks, Dom John Thorne and Dom Roger James, where all three were fastened upon hurdles and dragged by horses to the top of Toe Hill which overlooks the town. Here they were hanged, drawn and quartered, Abbot Whiting's head being fastened over the gate of the now deserted abbey and his limbs exposed at Wells, Bath, Ilchester and Bridgewater." (60) The heads of two other large houses at Colchester Abbey and Reading Abbey were also executed in 1539. (61)

Primary Sources

(1) Eustace Chapuys was King Charles V of Spain's ambassador in England. In 1537 Chapuys sent a report to Charles V on the Pilgrimage of Grace.

It is feared that he (Henry) will not grant as he ought the demands of the northern people... The rebels... are sufficiently numerous to defend themselves, and there is every expectation that... the number will increase, especially if they get some assistance in money from abroad.

(2) Robert Aske made a speech about the Pilgrimage of Grace in York in October 1536.

We have taken (this pilgrimage) for the preservation of Christ's church, of this realm of England, the King our sovereign lord, the nobility and commons of the same... the monasteries... in the north parts (they) gave great alms to poor men and laudably served God... and by occasion of the said suppression the divine service of Almighty God is much diminished.

(3) Edward Hall, History of England (1548)

They called this... a holy and blessed pilgrimage; they also had banners whereon was painted Christ hanging on the cross... With false signs of holiness... they tried to deceive the ignorant people.

(4) Derek Wilson, A Tudor Tapestry: Men, Women & Society in Reformation England (1972)

It would be incorrect to view the rebellion in Yorkshire, the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, as purely and simply an upsurge of militant piety on behalf of the old religion. Unpopular taxes, local and regional grievances, poor harvests as well as the attack on the monasteries and the Reformation legislation all contributed to the creation of a tense atmosphere in many parts of the country.

(5) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938)

The Pilgrimage of Grace... was a reactionary, Catholic movement of the North, led by the still half-feudal nobility of that area and aimed against the Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries. But if the leaders were nobles the mass character of the rising indicated a deep discontent and the rank and file were drawn in large measure from the dispossessed and from the threatened peasantry.

(6) Scott Harrison, The Pilgrimage of Grace in the Lake Counties (1981)

Including women and children the greatest assembly was that of fifteen thousand at the Broadfield. Twenty thousand men, women and children may have actively supported the rebellion at some stages, and many more may have taken the rebel oath before returning to their homes... If one accepts an estimate for the total population of the region of approximately seventy thousand in 1536, the fact that over one-third of the inhabitants were active rebels indicates a high level of involvement.

(7) S. J. Gunn, Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Appointed the king's lieutenant to suppress the Lincolnshire rebels, he advanced fast from Suffolk to Stamford, gathering troops as he went; but by the time he was ready to fight, the rebels had disbanded. On 16th October he entered Lincoln and began to pacify the rest of the county, investigate the origins of the rising, and prevent the southward spread of the pilgrimage.

(8) Indictment of John Bulmer (April 1537)

John Bulmer... with other traits, at Sherburn, Yorkshire, conspire to deprive the king of his title of Supreme Head of the English Church, and to compel him to hold a certain Parliament and Convocation of the clergy of the realm, and did commit diverse insurrections... at Pontefract, diverse days and times before the said 10th of October.

(9) Henry VIII gave orders to the Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk about what should happen to those who took part in the Pilgrimage of Grace (January, 1537)

Cause such dreadful executions upon a good number of the inhabitants hanging them on trees, quartering them, and setting the quarters in every town, as shall be a fearful warning.

(10) Thomas Cromwell, letter to Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk (22nd May, 1537)

The King's Highness also desireth your lordship that ye will make due search of such lands, offices, fees, farms, and all other things as were in the hands and possession of the Lord Darcy, Sir Robert Constable, Sir Francis Bigod, Sir John Bulmer, Sir Stephen Hamerton, Sir Thomas Percy, Nicholas Tempest, and all the persons of those parts lately attainted here and to certify the same to His Grace, to the intent the same may confer them to the persons worthy accordingly, and likewise to cause a perfect inventory of their goods, lands, and possessions to be made and sent up with convenient speed as shall appertain.

(11) Sentence of death for leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace quoted in the book, John Bellamy, The Tudor Law of Treason (1979)

You are to be drawn upon a hurdle to the place of execution, and there you are to be hanged by the neck, and being alive cut down, and your privy-members to be cut off, and your bowels to be taken out of your belly and there burned, you being alive; and your head to be cut off, and your body to be divided into four quarters, and that your head and quarters to be disposed of where his majesty shall think fit.

(12) Jasper Ridley, Henry VIII (1984)

Nearly all the noblemen and gentlemen of Yorkshire had joined the Pilgrimage of Grace in the autumn. Henry could not execute them all. He divided them, somewhat arbitrarily, into two groups - those who were to be forgiven and restored to office and favour, and those who were to be executed on framed-up charges of having committed fresh acts of rebellion after the general pardon. Archbishop Lee, Lord Scrope, Lord Latimer, Sir Robert Bowes, Sir Ralph Ellerker and Sir Marmaduke Constable continued to serve as Henry's loyal servants. Darcy, Aske, Sir Robert Constable, and Bigod were to die. So were Sir John Bulmer and his mistress, Margaret Cheyney, who was known as Lady Bulmer but was not lawfully married to him.

(13) John Guy, Tudor England (1986) page 151

Leaders executed including Lord Darcy and Hussey, Sir Robert Constable, Sir Thomas Percy, Sir Francis Bigod, Sir John Bulmer, and Robert Aske. Clerical victims were James Cockerell of Guisborough Priory, William Wood, prior of Bridlington, Friar John of Pickering, Adam Sedbar, abbot of Jervaux, and William Thirsk of Fountains Abbey.

(14) Thomas Cromwell, letter to Thomas Wyatt (June, 1537)

Nothing is succeeded since my last writing but from good quiet and peace daily to better and better. Thetraitors have been executed, the Lord Darcy at Tower Hill, the Lord Hussey at Lincoln, Aske hanged upon the dungeon of the castle of York, and Sir Robert Constable hanged at Hull. The residue were executed at Tyburn.

Student Activities

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

The Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)