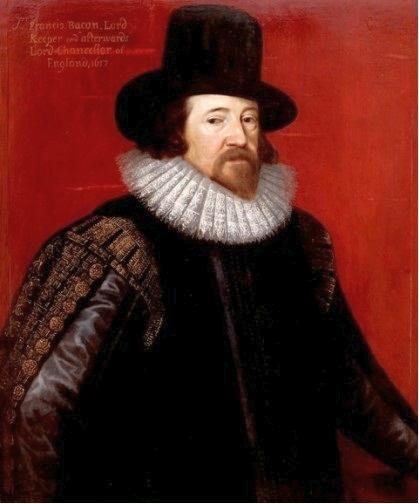

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon and his second wife, Anne Cooke Bacon, was born at York House in the Strand, London, on 22nd January 1561. His father was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Queen Elizabeth. His mother was the daughter of Sir Anthony Cooke, the tutor to Edward VI. (1)

Bacon spent most of his childhood with his elder brother, Anthony Bacon, at the family home at Gorhambury House, near St Albans. His mother who was fluent in Greek and Latin as well as in Italian and French, played an important role in his education. His schooling not only included Christian teaching but also thorough training in the classics. (2)

Anthony and Francis (who had just turned twelve) went up to Trinity College on 5th April 1573. He was described as an "academically precocious child". (3) The brothers were put under the personal tutelage of the master, Dr John Whitgift, the future archbishop of Canterbury. (4) According to the accounts kept by Whitgift he bought for the Bacon brothers' use the major classical texts and commentaries. These included the Iliad, Plato and Aristotle, Cicero's rhetorical works, Demosthenes' Orations... as well as the histories of Livy, Sallust, and Xenophon". (5) Bacon later complained about his time at university as it was "barren of the production of works for the benefit of the life of man". (6)

Early career of Francis Bacon

Bacon left Cambridge University in December 1575. The following year he joined Gray's Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris. For the next three years he visited Italy, and Spain. During his travels, Bacon studied languages and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks for Francis Walsingham, William Cecil and Robert Dudley.

According to his first biographer, Pierre Amboise, "Bacon spent several years of his youth in travels, to polish his wit and form his judgement, by reference to the practice of foreigners. France, Italy and Spain, being the countries of highest civilization, were those to which this curiosity drew him. As he saw himself destined to hold in his hands one day the helm of the Kingdom, he did not look only at the scenery, and the clothes of the different peoples... but took note of the different types of government, the advantages and the faults of each, and of all things the understanding of which should fit a man to govern?" (7)

Anne Bacon was a supporter of Thomas Cartwright the Puritan preacher. As Roger Lockyer has pointed out: "Cartwright, who was only in his mid-thirties, represented a new generation of Elizabethan puritans, who took the achievements of their predecessors for granted and wished to push forward from the positions that they had established. Cartwright declared that the structure of the Church of England was contrary to that prescribed by Scripture, and that the correct model was that which Calvin had established at Geneva. Every congregation should elect its own ministers in the first instance, and control of the Church should be in the hands of a local presbytery, consisting of the minister and the elders of the congregation. The authority of archbishops and bishops had no foundation in the Bible, and was therefore unacceptable. Cartwright's definition lifted the puritan movement out of its obsession with details and threw down a challenge which the established Church could not possibly ignore." (8)

The death of his father, Sir Nicholas Bacon, forced him to return to England. Paulet provided a letter of introduction to Queen Elizabeth that said he "would prove a very able and sufficient subject to do her Highness good and acceptable service... if God give him life". (9) This was a reference to the fact that he was often ill during this period.

Despite Paulet's letter, he failed to find work with the Queen even though he has been described as a "genius". He wrote to his uncle William Cecil, the Lord Treasurer, asking him to petition the Queen for a government post. Apparently he refused to do this. (10) It has been claimed he did not want his son Robert Cecil, "clever, dearly loved of his father and a hunchback" to be overshadowed by the highly talented Bacon. (11)

Francis Bacon become a lawyer. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. His income being supplemented by a grant of his mother Lady Anne Bacon of the manor of Marks in Essex which generated a rent of £46. He was admitted to the bar as a barrister in June 1582. Bacon became the MP for Melcombe Regis.

In the House of Commons showed signs of sympathy to puritanism and often attended the sermons of Walter Travers. By 1584 Bacon, together with many key figures in the political nation, had become alarmed by both the perceived growing Catholic threat and the English church's suppression of the puritan clergy. Robert Lacey has commented: "A discreet homosexual, he had no intimate friends save the beautiful boys he seldom kept long, but he everywhere earned respect for his painstaking work and attention to detail." (12)

Bacon's main enemy was his former tutor, Dr John Whitgift, who was leading an anti-puritan campaign. In a pamphlet written by Bacon. "He strongly criticized the Catholics both within and without England and gave support for the puritan cause. But his argument was couched in strongly political terms. He appealed to ‘all reason of state’ and to the example ‘of the most wise, most politic, and best governed estates’. For the danger within the queen should do everything possible to strengthen protestantism, mainly through promoting preaching and schooling, because all her ‘force and strength and power’ consisted in her protestant subjects." (13)

Francis Bacon suggested to Queen Elizabeth should follow a policy of religious toleration. Philippa Jones has argued: "Francis wrote a lengthy report on the situation to the Queen, suggesting that more might be achieved if penalties against Catholics were relaxed, thus removing some of the cause of their discontent and the temptation to join in with any treasonable plots." (14)

Intelligence Service

Francis Bacon was employed by England's spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham to investigate English Catholics. In the parliament which met in winter 1586–7 Bacon argued for the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, and was named to the committee appointed to draw up a petition for her execution. In August 1588 Bacon was appointed to a government committee examining recusants in prison and a few months later, in December 1588, he was appointed to a committee of lawyers which was to review existing statutes. (15)

Bacon became close to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex in 1592. (16) He was one of Queen Elizabeth's most important advisers and since the death of Walsingham had taken command of the intelligence service. (17) Essex was impressed with Bacon and decided to recruit him and his brother, Anthony Bacon. Essex's biographer, Robert Lacey, has pointed out: "In the spring of 1592 Essex and the Bacon brothers found themselves outside the citadel of real political power: but possessing between them the intelligence, the industry, the contacts, the wealth and the pedigree they needed to force an entry. The story of the next six years is the story of how between them they did just that and carved out for themselves a position of potentially overwhelming might." (18)

The men joined forces in developing the case against Roderigo Lopez, the personal physician to Queen Elizabeth. As Anna Whitelock has pointed out: "As the Queen's physician, Lopez had a dual task: the preservation of the body of the Queen in her Bedchamber. Elizabeth liked and trusted him and granted him a valuable perquisite: a monopoly for importing aniseed and other herbs essential to the London apothecaries." (19)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Essex asked Thomas Phelippes to investigate Lopez. He discovered a secret correspondence between Estevão Ferreira da Gama, and the count of Fuentes, in the Spanish Netherlands. This was followed by the arrest of Lopez's courier, Gomez d'Avila. When he was interrogated he implicated Lopez. Phelippes also discovered a letter that stated: "The King of Spain had gotten three Portuguese to kill her Majesty and three more to kill the King of France". (20)

On 28th January 1594, Essex, wrote a letter to Anthony Bacon: "I have discovered a most dangerous and desperate treason. The point of conspiracy was her Majesty's death. The executioner should have been Doctor Lopez. The manner by poison. This I have so followed that I will make it appear as clear as the noon day." (21)

Essex employed Francis Bacon to write up the evidence against Roderigo Lopez and this was used against him at his trial. Sir Edward Coke, the Attorney-General, opened the trial by arguing that Lopez and his associates had been seduced by Jesuit priests with great rewards to kill the Queen "being persuaded that it is glorious and meritorious, and that if they die in the action, they will inherit heaven and be canonised as saints". He pointed out that Lopez was "her Majesty's sworn servant, graced and advanced with many princely favours, used in special places of credit, permitted often access to her person, and so not suspected... This Lopez, a perjuring murdering traitor and Jewish doctor, more than Judas himself, undertook the poisoning, which was a plot more wicked, dangerous and detestable than all the former." (22)

Coke emphasized the three men's secret Judaism and they were all convicted of high treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. (23) However, the Queen remained doubtful of her doctor's guilt and delayed giving the approval needed to carry out the death sentences. William Cecil wanted to ensure that Lopez was executed to protect himself from a possible investigation. "From Cecil's point of view Lopez knew too much and therefore had to be silenced". (24) Roderigo Lopez, Manuel Luis Tinoco, and Estevão Ferreira da Gama were executed at Tyburn on 7th June 1594.

Conflict with Queen Elizabeth

Essex proposed to Queen Elizabeth that Francis Bacon should become her attorney-general. However, his behaviour in the House of Commons showed that he would not automatically support government policies. Bacon opposed extra taxes needed to carry out future military action. He argued that this proposed new tax would cause economic problems for his constituents: "The gentlemen must sell their plate and the farmers their brass pots were this will be paid. And as for us, we are here to search the wounds of the realm and not to skin them over". (25)

Bacon proposed that the collection of this tax should be spread over six instead of four years. This brought Bacon into conflict with Robert Cecil and other ministers of the crown. When in the course of the next few months, Bacon attempted to secure for himself "a government office of prominence and profit" he was "sharply rebuffed". As Robert Lacey, the author of Robert, Earl of Essex (1971) has pointed out: "The speech that had been intended simply to discomfort the Cecils had discomforted the Queen as well." (26)

Queen Elizabeth told William Cecil that she thought that Bacon was "in more fault than any of the rest in Parliament". As soon as Cecil had informed him of the queen's anger Bacon tried to excuse his speech. "The manner of my speech", he told his uncle, "did most evidently show that I spake simply and only to satisfy my conscience, and not with any advantage or policy to sway the cause". In expressing his sincere opinions Bacon had simply endeavoured to signify his "duty and zeal towards her Majesty and her service".

Realizing that he had miscalculated the impact his speeches would have on the Queen and he told Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, that he would "retire myself with a couple of men to Cambridge, and there spend my life in my studies and contemplations, without looking back". No such retirement took place. In July 1594 the queen made Bacon one of her learned counsel and he was employed in several legal cases. (27)

Publication of Essays

In January 1597 Francis Bacon published Essays. It has been claimed that it was "the most revolutionary little book to leave the English printing press until then... Bacon's Essays were consummate art, significant not simply in their own right but in the context of English prose was born with their publication." (28) Henry Hallam, the author of Introduction to the Literature of Europe in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries (1854) agrees and wrote that "They are deeper and more discriminating than any earlier, or almost any later, work in the English language". (29)

Bacon tackled a variety of different subjects. This included highly controversial issues such as religion and democracy: "A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny; as that of the Turks. For nobility attempters sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles.... It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings. A numerous nobility causeth poverty, and inconvenience in a state; for it is a surcharge of expense; and besides, it being of necessity, that many of the nobility fall, in time, to be weak in fortune, it maketh a kind of disproportion, between honor and means."

Bacon also dealt with more personal issues such as friendship and parenthood: "The joys of parents are secret; and so are their griefs and fears. They cannot utter the one; nor they will not utter the other. Children sweeten labors; but they make misfortunes more bitter. They increase the cares of life; but they mitigate the remembrance of death. The perpetuity by generation is common to beasts; but memory, merit, and noble works, are proper to men. And surely a man shall see the noblest works and foundations have proceeded from childless men; which have sought to express the images of their minds, where those of their bodies have failed. So the care of posterity is most in them, that have no posterity. They that are the first raisers of their houses, are most indulgent towards their children; beholding them as the continuance, not only of their kind, but of their work; and so both children and creatures." (30)

In this essay Francis Bacon revealed his own feelings about being the youngest child and a secret homosexual. (31) "The difference in affection, of parents towards their several children, is many times unequal; and sometimes unworthy; especially in the mothers; as Solomon saith, A wise son rejoiceth the father, but an ungracious son shames the mother. A man shall see, where there is a house full of children, one or two of the eldest respected, and the youngest made wantons; but in the midst, some that are as it were forgotten, who many times, nevertheless, prove the best. The illiberality of parents, in allowance towards their children, is an harmful error; makes them base; acquaints them with shifts; makes them sort with mean company; and makes them surfeit more when they come to plenty. And therefore the proof is best, when men keep their authority towards the children, but not their purse. Men have a foolish manner (both parents and schoolmasters and servants) in creating and breeding an emulation between brothers, during childhood, which many times sorteth to discord when they are men, and disturbeth families." (32)

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

Following his successful raid on the Spanish navy in Cadiz, Bacon's patron, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, had a flaming disagreement with Queen Elizabeth. She was furious with Essex for giving the booty from Cadiz to his men. She ordered William Cecil to carry out an investigation into Essex's conduct of the campaign. He was eventually cleared of incompetence but it has been claimed that Elizabeth never forgave him for his actions. (33) Essex had hoped to be appointed to the prestigious and lucrative post of master of the Court of Wards. According to Roger Lockyer the Queen refused to give him what he wanted because she "distrusted his popularity and also resented the imperious manner in which he claimed advancement. (34)

In February 1597 Francis Bacon decided that Essex was a dangerous man to be associated with and wrote to William Cecil apologizing for work he had carried out in the past on Essex's behalf that might have been opposed to those of Cecil's: "In like humble manner I pray your Lordship to pardon mine errors, and not to impute unto me the errors of any other... but to conceive of me to be a man that daily profiteth in duty." (35)

This was a sensible move because on 7th February, 1601, Essex was visited by a delegation from the Privy Council and was accused of holding unlawful assemblies and fortifying his house. Fearing arrest and execution he placed the delegation under armed guard in his library and the following day set off with a group of two hundred well-armed friends and followers, entered the city. Essex urged the people of London to join with him against the forces that threatened the Queen and the country. This included Robert Cecil and Walter Raleigh. He claimed that his enemies were going to murder him and the "crown of England" was going to be sold to Spain. (36)

At Ludgate Hill his band of men, that included his step-father, Sir Christopher Blount, were met by a company of soldiers. As his followers scattered, several men were killed and Blount was seriously wounded. (37) Essex and about 50 men managed to escape but when he tried to return to Essex House he found it surrounded by the Queen's soldiers. Essex surrendered and was imprisoned in the Tower of London. (38)

On 19th February, 1601, Essex and some of his men were tried at Westminster Hall. He was accused of plotting to deprive the Queen of her crown and life as well as inciting Londoners to rebel. Essex protested that "he never wished harm to his sovereign". The coup, he claimed was merely intended to secure access for Essex to the Queen". He believed that if he was able to gain an audience with Elizabeth, and she heard his grievances, he would be restored to her favour. Essex was found guilty of treason and was executed on 25th February. (39)

Francis Bacon and Water Rayleigh

In the last Elizabethan parliament, which met in October 1601, Bacon sat for Ipswich. He supported the subsidy bill of four subsidies and emphasized that the poor as well as the rich should contribute. This brought him into conflict with Walter Raleigh. Bacon also insisted that parliament, as well as raising money, must enact laws. He brought in a bill "against abuses in weights and measures" and spoke "for repealing superfluous laws’.

Bacon and Raleigh also argued against each other in a debate about the renewal of the Statute of Tillage. Bacon defended the bill, which enacted that land converted to pasture should be restored to tillage, noting that "the husbandman", being "a strong and hardy man", made the best soldier. Raleigh replied that since "all Nations abound with Corn" it was best "to set it at Liberty, and leave every man Free, which is the Desire of a true Englishman". Bacon's view, receiving support from his cousin Robert Cecil, prevailed. (40)

King James I

Queen Elizabeth died on 24th March, 1603. The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. The following year, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the he 14-year-old daughter of a well-connected London merchant Benedict Barnham. According to Robert Lacey "it was not until the reign of James that he achieved the eminence for which he had always been prepared to sacrifice so much self respect". (41)

In 1603 Bacon also published a short treatise on the proposed union between England and Scotland entitled A Brief Discourse Touching the Happy Union of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. This was a work of propaganda on behalf of the king. Privately, Bacon had his doubts, thinking that the king "hastened to a mixture of both kingdoms and nations, faster perhaps than policy will conveniently bear" but on the whole he fully supported the union. He wrote about the importance of uniting "these two mighty and warlike nations of England and Scotland into one kingdom". (42)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In October 1605 he published his first philosophical book, The Advancement of Learning. The work was a general survey of the contemporary state of human knowledge, identifying its deficiencies and supplying Bacon's broad suggestions for improvement. Roger Lockyer, the author of Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985) has argued that Bacon was the first major English figure in the scientific revolution. "Francis Bacon... made himself the propagandist of the scientific method and constantly urged the need for experiment and research. The high position that he held and the fame of his name formed a shelter behind which enquiring men could pursue their researches, and the freedom given to scientific speculation in England may account for the fact that by the late seventeenth century London had become the capital of the scientific as well as the commercial world. It was Bacon's hope that academies would be formed where scientists could exchange information, for he recognised the paramount importance of communications to the spread of knowledge." (43)

Francis Bacon held the important posts of Solicitor General (1607), Attorney General (1613) and Lord Chancellor (1618). In 1620 he published Novum Organum Scientiarum (New Instrument of Science). In the book he argued: "The sciences which we possess come for the most part from the Greeks. But from all these systems of the Greeks, and their ramifications through particular sciences, there can hardly after the lapse of so many years be adduced a single experiment which tends to relieve and benefit the condition of man." (44)

Matthew Syed believes that this was "a truly devastating assessment" as he was suggesting that since the Greeks scientific progress had not been taking place. "The teachings of the early church were brought together with the philosophy of Aristotle (who had been elevated to a revered authority) to create a new, sacrosanct worldview. Anything that contradicted Christian teaching was considered blasphermous. Dissenters were published." (45)

In 1621 he was impeached by Parliament for bribery and corruption. (46) Not since the fifteenth century had a great officer of the crown been overthrown in Parliament. Bacon expected to be protected by James I but he told the "Lords that while they should proceed with all due care they should not scruple to pass judgment where they found good cause". When he heard this was the view of the king he acknowledged his guilt. (47)

Bacon was fined £40,000 and "imprisonment at the king's pleasure". He was also barred from any office or employment in the state and forbidden to sit in parliament or come within the verge (12 miles) of the court. The fine was never collected and his imprisonment in the Tower of London lasted only three days. (48)

Francis Bacon, died aged 65, on 9th April 1626.

Primary Sources

(1) Elizabeth Jenkins, Elizabeth the Great (1958)

The tone among the men of Elizabeth's last circle was one of clamorous self assertion, varied by a passionate sense of ill-usage, amounting to stark tragedy, if their material ambitions were postponed or thwarted. This was notably so in Raleigh and Essex, and more discreetly expressed it was found in the third faction, the two sons of the late Lord Keeper, Antony and Francis Bacon. One was exceedingly able and the other a genius, but their uncle by marriage, Lord Burleigh, did not advance them. The Lord Treasurer wanted to keep all his benefits for his son Robert Cecil, clever, dearly loved of his father and a hunchback. The latter was eminently prudent and well-behaved; the rest eyed the Queen like famished hounds and snarled if she gave something to anybody else.

(2) Robert Lacey, Robert, Earl of Essex (1971)

Judicious bribes and flattery had bought him the seat for Melcombe in Dorset for the 1584 Parliament, and in 1586 he represented Taunton. He was a member of one of the committees set to work out the details of a special financial "benevolence" to help the Queen through the height of the crisis with Spain, and in t589 he sat on another committee that drew up provisions for a special double subsidy to meet the cost of reorganizing national defences against the possibility of a second Armada.

A discreet homosexual, he had no intimate friends save the beautiful boys he seldom kept long, but he everywhere earned respect for his painstaking work and attention to detail. It was a precise reflection of Elizabethan society that in 1592, after over a dozen years of hard work and closely applied intelligence, Francis Bacon's greatest good fortune was to become the hired retainer of an Earl infinitely his inferior in wit and nine years his junior but whom inheritance, good looks, a stepfather and three undistinguished military escapades had made one of the greatest in the land.

And it was the young Earl's good fortune on returning from France to meet not only Francis Bacon but his yet more intelligent and certainly more loyal elder brother, Anthony. Anthony had been at Trinity with Francis in 1573 and had also gone abroad to learn the intricacies of the diplomatic service. But when their father died in 1579 Anthony had opted to stay on the Continent. The two brothers had been entrusted by old Sir Nicholas to the care of the great Lord Burghley whose wife Mildred was their aunt - a sister of their mother's. Yet Burghley greeted all Anthony's requests for help with "fair words, with no show of real kindness". So while Francis had to fight for a living at Gray's Inn, Anthony roamed the courts of Europe as a freelance spy cum scholar. He sent back intelligence reports on diplomatic developments to Sir Francis Walsingham in London, and picked up extra money as a secretary and adviser who could command a variety of languages and an ever-widening circle of contacts.

Though troubled by weak eyes, gout and the stone he lived on his wits, and when to the joy of Francis and his mother he decided to return to England early in 1592, he was an accomplished and valuable asset to any courtier with serious political ambitions. How Essex and the Bacon brothers came together at this critical juncture in all their careers is uncertain. Francis and Essex had probably met before. And the whole trio had connections with Lord Burghley which the old man had at various times gently but firmly declined to turn into obligations: two penniless title-less and somewhat over-intelligent brothers had little to offer a man endowed with all the intelligence he needed: and the Earl of Essex had been tied too obviously to the Leicester bandwagon to expect success from his attempts to chum up with Lord Burghley's faction. Besides, Burghley had his own son Robert whom he was grooming for future office.

So in the spring of 1592 Essex and the Bacon brothers found themselves outside the citadel of real political power: but possessing between them the intelligence, the industry, the contacts, the wealth and the pedigree they needed to force an entry. The story of the next six years is the story of how between them they did just that and carved out for themselves a position of potentially overwhelming might: and the story of the three years following - which ended with that private execution in the Tower of London - is the story of how the Earl of Essex threw away all that the three of them had so skilfully achieved.

(3) Pierre Amboise, The Life of Francis Bacon (1631)

Mr Bacon spent several years of his youth in travels, to polish his wit and form his judgement, by reference to the practice of foreigners. France, Italy and Spain, being the countries of highest civilisation, were those to which this curiosity drew him. As he saw himself destined to hold in his hands one day the helm of the Kingdom, he did not look only at the scenery, and the clothes of the different peoples... but took note of the different types of government, the advantages and the faults of each, and of all things the understanding of which should fit a man to govern?

(4) Francis Bacon, Essays (1597)

We will speak of nobility, first as a portion of an estate, then as a condition of particular persons. A monarchy, where there is no nobility at all, is ever a pure and absolute tyranny; as that of the Turks. For nobility attempters sovereignty, and draws the eyes of the people, somewhat aside from the line royal. But for democracies, they need it not; and they are commonly more quiet, and less subject to sedition, than where there are stirps of nobles. For men’s eyes are upon the business, and not upon the persons; or if upon the persons, it is for the business’ sake, as fittest, and not for flags and pedigree. We see the Switzers last well, notwithstanding their diversity of religion, and of cantons. For utility is their bond, and not respects. The united provinces of the Low Countries, in their government, excel; for where there is an equality, the consultations are more indifferent, and the payments and tributes, more cheerful. A great and potent nobility, addeth majesty to a monarch, but diminisheth power; and putteth life and spirit into the people, but presseth their fortune. It is well, when nobles are not too great for sovereignty nor for justice; and yet maintained in that height, as the insolency of inferiors may be broken upon them, before it come on too fast upon the majesty of kings. A numerous nobility causeth poverty, and inconvenience in a state; for it is a surcharge of expense; and besides, it being of necessity, that many of the nobility fall, in time, to be weak in fortune, it maketh a kind of disproportion, between honor and means.

As for nobility in particular persons; it is a reverend thing, to see an ancient castle or building, not in decay; or to see a fair timber tree, sound and perfect. How much more, to behold an ancient noble family, which has stood against the waves and weathers of time! For new nobility is but the act of power, but ancient nobility is the act of time. Those that are first raised to nobility, are commonly more virtuous, but less innocent, than their descendants; for there is rarely any rising, but by a commixture of good and evil arts. But it is reason, the memory of their virtues remain to their posterity, and their faults die with themselves. Nobility of birth commonly abateth industry; and he that is not industrious, envieth him that is. Besides, noble persons cannot go much higher; and he that standeth at a stay, when others rise, can hardly avoid motions of envy. On the other side, nobility extinguisheth the passive envy from others, towards them; because they are in possession of honor. Certainly, kings that have able men of their nobility, shall find ease in employing them, and a better slide into their business; for people naturally bend to them, as born in some sort to command.

(5) Francis Bacon, Essays (1597)

The joys of parents are secret; and so are their griefs and fears. They cannot utter the one; nor they will not utter the other. Children sweeten labors; but they make misfortunes more bitter. They increase the cares of life; but they mitigate the remembrance of death. The perpetuity by generation is common to beasts; but memory, merit, and noble works, are proper to men. And surely a man shall see the noblest works and foundations have proceeded from childless men; which have sought to express the images of their minds, where those of their bodies have failed. So the care of posterity is most in them, that have no posterity. They that are the first raisers of their houses, are most indulgent towards their children; beholding them as the continuance, not only of their kind, but of their work; and so both children and creatures.

The difference in affection, of parents towards their several children, is many times unequal; and sometimes unworthy; especially in the mothers; as Solomon saith, A wise son rejoiceth the father, but an ungracious son shames the mother. A man shall see, where there is a house full of children, one or two of the eldest respected, and the youngest made wantons; but in the midst, some that are as it were forgotten, who many times, nevertheless, prove the best. The illiberality of parents, in allowance towards their children, is an harmful error; makes them base; acquaints them with shifts; makes them sort with mean company; and makes them surfeit more when they come to plenty. And therefore the proof is best, when men keep their authority towards the children, but not their purse. Men have a foolish manner (both parents and schoolmasters and servants) in creating and breeding an emulation between brothers, during childhood, which many times sorteth to discord when they are men, and disturbeth families. The Italians make little difference between children, and nephews or near kinsfolks; but so they be of the lump, they care not though they pass not through their own body. And, to say truth, in nature it is much a like matter; insomuch that we see a nephew sometimes resembleth an uncle, or a kinsman, more than his own parent; as the blood happens. Let parents choose betimes, the vocations and courses they mean their children should take; for then they are most flexible; and let them not too much apply themselves to the disposition of their children, as thinking they will take best to that, which they have most mind to. It is true, that if the affection or aptness of the children be extraordinary, then it is good not to cross it; but generally the precept is good... Younger brothers are commonly fortunate, but seldom or never where the elder are disinherited.

(6) Roger Lockyer, Tudor and Stuart Britain (1985)

The first major English figure in the scientific revolution was not, however, a practising scientist. Francis Bacon, a distinguished lawyer who became James I's Lord Chancellor, made himself the propagandist of the scientific method and constantly urged the need for experiment and research. The high position that he held and the fame of his name formed a shelter behind which enquiring men could pursue their researches, and the freedom given to scientific speculation in England may account for the fact that by the late seventeenth century London had become the capital of the scientific as well as the commercial world. It was Bacon's hope that academies would be formed where scientists could exchange information, for he recognised the paramount importance of communications to the spread of knowledge. No such academy was founded during his lifetime, but the Royal Society acknowledged him as its spiritual founder, and his picture appears next to the bust of Charles II in its official history.

(7) Francis Bacon, quotations.

All colours agree in the dark.

Money is like manure, of very little use except it be spread.

Whosoever is delighted in solitude is either a wild beast or a god.

Hope is a good breakfast, but is a bad supper.

To live is like love. All reason is against it, and all healthy instinct for it.

I will never be an old man. To me, old age is always 15 years older than I am.

Knowledge is power.

Small amounts of philosophy lead to atheism, but larger amounts bring us back to God.

Wives are young men's mistresses, companions for middle age, and old men's nurses.

There is no comparison between that which is lost by not succeeding and that which is lost by not trying.

Who questions much, shall learn much, and retain much.

If we do not maintain justice, justice will not maintain us.

Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.

The worst solitude is to have no real friendships.

People usually think according to their inclinations, speak according to their learning and ingrained opinions, but generally act according to custom.

I do not believe that any man fears to be dead, but only the stroke of death.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)