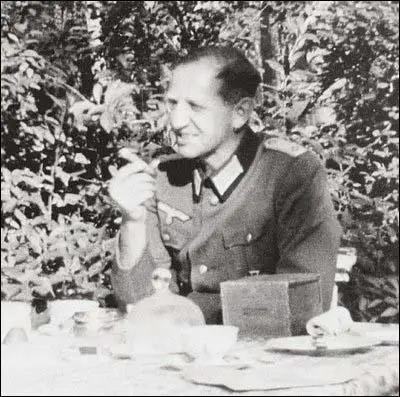

Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg

Fritz-Dietlof Graf von der Schulenburg, was born in London on 5th September 1902. At the time, his father, Count Friedrich Bernhard von der Schulenburg, was the German Empire's military attaché. As a result of his father's occupation, Schulenburg, his four brothers, and their sister, grew up in several different places, including Berlin, Potsdam and Münster. (1)

His father was a successful general in the First World War. Schulenburg refused to join the military and instead studied law at the University of Göttingen and the University of Marburg. During this period, according to Hans Gisevius, he "toyed with Communistic ideas". (2)

In 1923, Schulenburg became a trainee civil servant in Potsdam. During this period he held socialist views and was nicknamed the "Red Count". Five years later he became a civil servant in Recklinghausen. Schulenburg gradually changed his political views and became increasingly disillusioned with the economic situation in Germany and became attracted to the ideas of Adolf Hitler. In October, 1932, he joined the Nazi Party as he wanted to "play an active part in the political battle". (3)

Schulenburg was delighted when Hitler became chancellor of Germany. One of the reasons for this was he was deeply anti-Semitic and strongly nationalist. He wrote that the establishment of the Third Reich represented a major defeat for the "powers of Jewry, capital, and the Catholic Church". The Weimar Republic had destroyed "the old Prussian civil service, which possessed outstanding qualities of intelligence, character, and accomplishment." It all changed when Hitler created a new core of resistance, so that the Nazi movement became "the incarnation of the faith and will of the German people." (4)

In March 1933, Schulenburg was appointed to the government council in Königsberg and gained increasing influence, both as a government official and as a member of the Nazi Party. Schulenburg was a supporter of Gregor Strasser and Ernst Röhm, the leaders of the left-wing group within the Nazi Party. On the evening of 28th June, 1934, Hitler telephoned Röhm to convene a conference of the Sturmabteilung (SA) leadership at Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse, two days later. "The call served the double purpose of gathering the SA chiefs in one out-of-the-way spot, and reassuring Röhm that, despite the rumours flying about, their mutual compact was safe. No doubt Röhm expected the discussion to centre on the radical change of government in his favour promised for the autumn." (5)

The following day Hitler held a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. He told him that he had decided to act against Röhm and the SA. Hitler felt he could not take the risk of "breaking with the conservative middle-class elements in the Reichswehr, industry, and the civil service". By eliminating Röhm he could make it clear that he rejected the idea of a "socialist revolution". Although he disagreed with the decision, Goebbels decided not to speak out against "Operation Humingbird" in case he was also eliminated. (6)

At around 6.30 in the morning of 30th June, Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. (7) Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic." (8)

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Executions nearly finished. A few more are necessary. That is difficult, but necessary... It is difficult, but is not however to be avoided. There must be peace for ten years. The whole afternoon with the Führer. I can't leave him alone. He suffers greatly, but is hard. The death sentences are received with the greatest seriousness. All in all about 60." (9)

Hitler made a speech where he stated that he acted as "the Supreme Justiciar of the German Volk" and had used this violence "to prevent a revolution". A retrospective law was passed to legitimize the murders. The German judiciary made no protest about the use of the law to legalize murder. These events, however, had a major impact on the outside world: "The killings of 30 June and succeeding days were also an important moment in the history of the Nazi movement. Before the people of Germany, and the outside world, the leaders of the Party were revealed as calculating killers." (10)

The purge of the SA was kept secret until it was announced by Hitler on 13th July. It was during this speech that Hitler gave the purge its name: Night of the Long Knives (a phrase from a popular Nazi song). Hitler claimed that 61 had been executed while 13 had been shot resisting arrest and three had committed suicide. One of those murdered was Schulenburg's friend, Gregor Strasser. It has been argued that as many as 400 people were killed during the purge. In his speech Hitler explained why he had not relied on the courts to deal with the conspirators: "In this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German people, and thereby I become the supreme judge of the German people. I gave the order to shoot the ringleaders in this treason." It is not known exactly how many people were murdered between 30th June and 2nd July, when Hitler called off the killings. "Bodies were found in fields and woods for weeks afterwards and files of petitions from relatives of the missing remained active for months. What seems certain is that less than half were SA officers." (11)

Despite this purge of people like Röhm and Strasser, Schulenburg remained a supporter of Hitler. He told friends apologetically that he was aware of the "shady side of the Party" and that it was full of irregular goings-on and dubious individuals. However, he had come to the conclusion that "no rallying of the people is possible under any other banner". This equated with the notion, widespread among the middle-class right-wing camp, and deliberately nurtured by Nazi propaganda, that the "popular movement" of Nazism was instrumental in the drive towards a profound, epoch-making and all-embracing regeneration of the state and Volk." (12)

Schulenburg increasingly came into conflict with his superior, Erich Koch, the President of East Prussia. In 1937 it was decided to arrange for him to be transferred to the German Interior Ministry and was posted to Berlin as vice president of police. His immediate superior was the Berlin President of Police Wolf-Heinrich Helldorf, who was also starting to have doubts about Hitler. Helldorf was absent in Berlin during Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938). On his return he called a conference of police officers and berated them for their passivity during the riots against the Jews. He told them that if he had been present he would have ordered his men to shoot all rioters and looters. (13)

Schulenburg fully supported Germany at the beginning of the Second World War. He believed Germany should head east to destroy communism in the Soviet Union. Schulenburg convinced himself that, once the Bolshevist system had been stamped out, the peoples of Eastern Europe could live in harmony under German supremacy. He believed that the Third Reich was destined to assume the task of "replacing parasitic capitalism by a social order based on communities". In 1939 he still felt that Hitler would provide the starting-point for a fundamental reshaping of state and society. (14)

This changed the following year and in 1940, Schulenburg joined the Kreisau Circle, a small group of intellectuals who opposed the Nazi Party. Other members included Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg, Helmuth von Moltke, Adam von Trott, Wilhelm Leuschner, Julius Leber, Adolf Reichwein, Alfred Delp, Eugen Gerstenmaier, Dietrich Bonhoffer and Jakob Kaiser. "Rather than a group of conspirators, these men were more of a discussion group looking for an exchange of ideas on the sort of Germany would arise from the detritus of the Third Reich, which they confidently expected ultimately to fail." (15)

Wartenburg and Moltke were free from the anti-Semitic prejudice so common among their class. Unlike many members of the resistance, nationalistic motives were only of secondary importance. "Both men made their judgments from a Christian and universalist viewpoint, and regarded the defeat of Nazism not primarily as a German problem, but one which genuinely concerned the whole western world. Neither of them faced the problem of having to separate a supposedly beneficial policy of segregation from criminally violent treatment of the Jews. For them, Jewish persecution had become symptomatic of the long decline of the west." (16)

However, not all the members took this view. Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg who believed that Jews should be eliminated from public service and evinced unmistakably anti-Semitic prejudice. "As late as 1938 he repeated his call for the removal of Jews from government and the civil service. His biographer, Albert Krebs, attests that he 'was never able to rid himself of feelings of alienation toward the intellectual and material world of Jewry.' He was appalled to learn of the crimes perpetrated against the Jewish population in the occupied Soviet Union, but this was not a major factor in his determination to see Hitler removed." (17)

In May, 1940, Schulenburg resigned as regional commissioner in Silesia and joined his reserve regiment, because he believed that he could serve the resistance more effectively from within the army. (18) Schulenburg joined forces with Eugen Gerstenmaier, a fellow member of the Kreisau Circle, to plot the assassination of Hitler. They decided to shoot Hitler while he was in Paris attending a parade on 20th July, 1940. On the appointed day Hitler failed to attend. According to Susan Ottaway, "because he realized that he had many enemies, he often changed his plans at the last moment". It may have been that he thought there would be more chance of something happening to him in an occupied country than in Germany. (19)

On 8th January, 1943, a group of conspirators, including Schulenburg, Helmuth von Moltke, Johannes Popitz, Ulrich Hassell, Ludwig Beck and Carl Goerdeler met at the home of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. Hassell was uneasy with the utopianism of the of the Kreisau Circle, but believed that the "different resistance groups should not waste their strength nursing differences when they were in such extreme danger". Wartenburg, Moltke and Hassell were all concerned by the suggestion that Goerdeler should become Chancellor if Hitler was overthrown as they feared that he could become a Alexander Kerensky type leader. (20)

Claus von Stauffenberg decided to carry out the assassination himself. But before he took action he wanted to make sure he agreed with the type of government that would come into being. Conservatives such as Carl Goerdeler and Johannes Popitz wanted Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben to become the new Chancellor. However, socialists in the group, such as Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner, argued this would therefore become a military dictatorship. At a meeting on 15th May 1944, they had a strong disagreement over the future of a post-Hitler Germany. (21)

Stauffenberg was highly critical of the conservatives led by Carl Goerdeler and was much closer to the socialist wing of the conspiracy around Julius Leber. Goerdeler later recalled: "Stauffenberg revealed himself as a cranky, obstinate fellow who wanted to play politics. I had many a row with him, but greatly esteemed him. He wanted to steer a dubious political course with the left-wing Socialists and the Communists, and gave me a bad time with his overwhelming egotism." (22)

The conspirators eventually agreed who would be members of the government. Head of State: Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, Chancellor: Carl Goerdeler; Vice Chancellor: Wilhelm Leuschner; State Secretary: Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg; Foreign Minister: Ulrich Hassell; Minister of the Interior: Julius Leber; State Secretary: Lieutenant Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg; Chief of Police: General-Major Henning von Tresckow; Minister of Finance: Johannes Popitz; President of Reich Court: General-Major Hans Oster; Minister of War: Erich Hoepner; State Secretary of War: General Friedrich Olbricht; Commander in Chief of Wehrmacht: Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben; Minister of Justice: Josef Wirmer. (23)

Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg also produced a document that suggested forming an European Union after the war: "The special thing about the European problem consists of there being, in a comparatively small area, a multiplicity of peoples who are to live together in a combination of unity and independence. Their unity must be so tight that war will never again be waged between them in future, and Europe's outside interests can be protected jointly... The solution of the European states can only be effected on a federative basis, with the European states incorporating themselves into a community of sovereign states by their own free decision." (24)

On 20th July, 1944, Stauffenberg entered the wooden briefing hut, twenty-four senior officers were in assembled around a huge map table on two heavy oak supports. Stauffenberg had to elbow his way forward a little in order to get near enough to the table and he had to place the briefcase so that it was in no one's way. Despite all his efforts, however, he could only get to the right-hand corner of the table. After a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying that he had to take a telephone call from Berlin. There was continual coming and going during the briefing conferences and this did not raise any suspicions. (25)

Stauffenberg went straight to a building about 200 hundred yards away consisting of bunkers and reinforced huts. Shortly afterwards, according to eyewitnesses: "A deafening crack shattered the midday quiet, and a bluish-yellow flame rocketed skyward... and a dark plume of smoke rose and hung in the air over the wreckage of the briefing barracks. Shards of glass, wood, and fiberboard swirled about, and scorched pieces of paper and insulation rained down." (26)

Stauffenberg observed a body covered with Hitler's cloak being carried out of the briefing hut on a stretcher and assumed he had been killed. He got into a car but luckily the alarm had not yet been given when they reached Guard Post 1. The Lieutenant in charge, who had heard the blast, stopped the car and asked to see their papers. Stauffenberg who was given immediate respect with his mutilations suffered on the front-line and his aristocratic commanding exterior; said he must go to the airfield at once. After a short pause the Lieutenant let the car go. (27)

According to eyewitness testimony and a subsequent investigation by the Gestapo, Stauffenberg's briefcase containing the bomb had been moved farther under the conference table in the last seconds before the explosion in order to provide additional room for the participants around the table. Consequently, the table acted as a partial shield, protecting Hitler from the full force of the blast, sparing him from serious injury of death. The stenographer Heinz Berger, died that afternoon, and three others, General Rudolf Schmundt, General Günther Korten, and Colonel Heinz Brandt did not recover from their wounds. Hitler's right arm was badly injured but he survived. (28)

However, General Erich Fellgiebel, Chief of Army Communications, sent a message to General Friedrich Olbricht to say that Hitler had survived the blast. The most calamitous flaw in Operation Valkyrie was the failure to consider the possibility that Hitler might survive the bomb attack. Olbricht told Hans Gisevius, they decided it was best to wait and to do nothing, to behave "routinely" and to follow their everyday habits. (29) Major Albrecht Metz von Quirnheim long closely involved in the plot, had already begun the action with a cabled message to regional military commanders, beginning with the words: "The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead." (30) As a result, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Ludwig Beck arrived at army headquarters in order to become members of the new government. (31).

Adolf Hitler had survived the blast. He was seized by a "titanic fury and an Unquenchable thirst for revenge" ordered Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Kaltenbrunner to arrest "every last person who had dared to plot against him". Hitler laid down the procedure for killing them: "This time the criminals will be given short shrift. No military tribunals. We'll hail them before the People's Court. No long speeches from them. The court will act with lightning speed. And two hours after the sentence it will be carried out. By hanging - without mercy." (32)

Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg was arrested along with Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg and Friedrich Olbricht. His trial took place on 7th August, 1944. It resulted in the conviction of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, General-Major Helmuth Stieff, General Paul von Hase (the commandant of the Berlin garrison) and several junior officers. All the men were tried by Roland Freisler, the notorious Nazi judge. Witzleben was especially badly treated. The Gestapo had taken away his false teeth and belt. He was "unshaven, collarless and shabby." It was claimed that he had aged ten years in two weeks of Gestapo captivity. (33)

Joseph Goebbels ordered that every minute of the trial should be filmed so that the movie could be shown to the troops and the civilian public as an example of what happened to traitors. (34) Wartenburg was particularly fearless and steadfast. He told the court: "The vital point running through all these questions is the totalitarian claim of the state over the citizen to the exclusion of his religious and moral obligation toward God." Schulenburg told Judge Freisler: "We have accepted the necessity to do our deed in order to save Germany from untold misery. I expect to be hanged for this, but I do not regret my action and I hope that someone else in luckier circumstances will succeed." (35)

All the men were found guilty and sentenced to hang that afternoon. Hitler had ordered that they be hung like cattle. "I want to see them hanging like carcasses in a slaughterhouse!" he commanded. The entire event was filmed by the Reich Film Corporation. "Witzleben was first. Despite his poor showing at the trial, Witzleben met his death with courage and with as much dignity as was possible under the circumstances. A thin wire noose was placed around his neck, and the other end was secured to a meat hook. The executioner and his assistant then picked up the sixty-four-year-old soldier and dropped him so that his entire weight fell on his neck. They then pulled off his trousers so that he hung naked and twisted in agony as he slowly strangled. It took him almost five minutes to die, but he never once cried out. The other seven condemned men were executed in the same manner within an hour." (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Hans Mommsen, Alternatives to Hitler (2003)

The anti-Semitism of Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg was more pronounced, since he was in no doubt that Jews should be eliminated from public service and evinced unmistakably anti-Semitic prejudice. As late as 1938 he repeated his call for the removal of Jews from government and the civil service. His biographer, Albert Krebs, attests that he "was never able to rid himself of feelings of alienation toward the intellectual and material world of Jewry." He was appalled to learn of the crimes perpetrated against the Jewish population in the occupied Soviet Union, but this was not a major factor in his determination to see Hitler removed.

(2) Joachim Fest, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997)

In May 1940 Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg resigned as regional commissioner in Silesia and joined his reserve regiment, because he believed that he could serve the resistance more effectively from within the army. Together with Eugen Gerstenmaier, a theologian and member of the Kreisau Circle, he attempted to form a commando unit to undertake Hitler's assassination. They failed, however, to assemble the nearly one hundred people required, and their plans were frustrated by transfers, orders to travel on official business at inopportune times, and Hitler's unpredictable changes of location.

(3) Susan Ottaway, Hitler's Traitors, German Resistance to the Nazis (2003) page 146

In July 1940 Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and fellow Kreisau Circle member, Eugen Gerstenmaier, decided to shoot Hitler while he was in Paris attending a parade. The parade was due to take place on 20 July and the two made their plans for the assassination. On the appointed day Hitler failed to attend. Perhaps because he realized that he had many enemies, he often changed his plans at the last moment and on this occasion he did just that... It may have been that he thought there would be more chance of something happening to him in an occupied country than in Germany.

Student Activities

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)