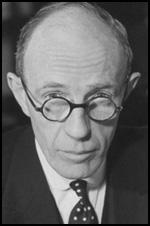

Lord Halifax

Edward Wood, the fourth son of the 2nd Viscount Halifax, was born in Powderham Castle, the home of his maternal grandfather, William Courtenay, 11th Earl of Devon, on 16th April, 1881. He was the sixth child and fourth son of Charles Lindley Wood (1839–1934), who later became the second Viscount Halifax, and his wife, Lady Agnes Elizabeth Courtenay (1838–1919). His great-grandfather was Earl Grey, the motivating force behind the 1832 Reform Act. Wood was born with an atrophied left arm that had no hand.

David Dutton has pointed out: "The Woods had emerged from among the gentry of Yorkshire to become one of the great landowning houses of northern England, but with three elder brothers Edward seemed to have little prospect of inheriting his father's title. Between 1886 and 1890, however, each of his brothers fell victim to one of the Victorian child-killing diseases, leaving him heir to the family viscountcy."

Wood went to St David's Preparatory School in September 1892 at the age of eleven. Two years later he transferred to Eton College. He did not enjoy his early schooling and was pleased to arrive at Christ Church, in October 1899. An outstanding student, he obtained a first-class degree in modern history from University of Oxford. He was also elected to a fellowship at All Souls in November 1903 and devoted himself over the next three years to further academic study, which led to the publication of a short biography of John Keble, one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement.

On 21st September 1909 he married Lady Dorheld government office oothy Evelyn Augusta Onslow (1885–1976), daughter of the William Onslow, 4th Earl of Onslow, who had served in the cabinet under Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury (1886-1889) and was a former governor-general of New Zealand. (1889-1892). The couple's first child, Anne, was born in July 1910. They also had three sons: Charles (1912), Peter (1916) and Richard (1920).

A member of the Conservative Party, Wood won the seat of Ripon from the Liberal candidate, Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch, in the 1910 General Election. As captain in the Queen's Own Yorkshire dragoons, a yeomanry regiment, he did not spend much time in the House of Commons during the First World War. However, when he did take part in debates, he joined Conservative hardliners who demanded all-out victory and a punitive peace with Germany. Wood spent time on the Western Front in 1916 and was relieved to be offered the post of deputy director of the labour supply department in the Ministry of National Service. He held this position to the end of the war. Robert Bernays later wrote: "He (Wood) has a magnificent head, and his tall figure and Cecilian stoop and sympathetic kindly eyes give more the impression of a Prince of the Church than a politician".

Ripon was a safe Conservative seat and at the elections of 1918, 1923, and 1924 Edward Wood was returned unopposed. In parliament Wood became a member of a small group of MPs which included Samuel Hoare, Philip Lloyd-Graeme, and Walter Elliot, whose aim was to espouse progressive policies. Wood was the co-author of The Great Opportunity (1918). As David Dutton has argued that Wood suggested that the "Conservative Party should focus on the welfare of the community rather than the advantage of the individual. It also advocated a federal solution to the Irish question." In April 1921 Wood was appointed under-secretary for the colonies in April 1921. In the winter 1921–2 Wood toured the British West Indies in order to report to Winston Churchill on the political and social situation there.

Wood became disillusioned with the leadership of David Lloyd George and was among the majority who voted at the Carlton Club on 23rd October, 1922 that the Conservative Party should contest the next general election as an independent force. With many leading Conservatives remaining loyal to Lloyd George, Wood was elevated from the obscurity of junior office to the ranks of the cabinet as president of the Board of Education on 24th October 1922. According to his biographer he regarded "it as little more than a stepping stone to higher office" and "made sure that his ministerial schedule left time for two days' hunting each week". He lost office when Ramsay MacDonald became the new prime minister following the 1924 General Election.

The Conservative Party returned to power in November 1924. In the government led by Stanley Baldwin Wood served as minister of agriculture on 6 November 1924. He held the post for less than a year for in October 1925 Wood was approached by the secretary of state for India, Lord Birkenhead, with the offer of the viceroyalty and governor-generalship in succession to Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading. He gave up his seat in the House of Commons and after accepting the title of Lord Irwin, left for India on 17th March 1926.

David Dutton has argued: " In many ways Irwin was well fitted for his new post. He relished the pomp which was inseparable from it. Physically, he cut an impressive figure, and was an accomplished horseman. Six feet five inches tall, he easily gave an impression of aristocratic self-confidence which set him apart from lesser men.... Yet at the same time he showed a sympathy for the Indian point of view unmatched by many of his predecessors. He also displayed considerable physical bravery in the face of more than one attempt to assassinate him during his time in the subcontinent. His viceroyalty was characterized by a patient commitment to ensuring that a contented India should remain inside the British Commonwealth for the foreseeable future. He set out to win Indian goodwill and co-operation, but could be firm when necessary, and stressed that it would be difficult to meet Indian wishes while Indians remained divided among themselves... In his first major speech as viceroy he appealed for an end to the endemic communal violence between Muslims and Hindus, and returned to this theme at intervals throughout his time in India. Towards terrorism he was uncompromising and, despite his Christian beliefs, felt no hesitation or remorse when signing death warrants which he considered justified."

Lord Irwin clashed with Winston Churchill over his dealings with Mohandas Gandhi, who he considered a "malignant subversive fanatic". On 17th February 1931, Irwin met Gandhi for the first of a series of discussions. When he heard the news Churchill commented: "It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well-known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace, while he is still organising and conducting a defiant campaign of civil disobedience, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor."

On 5th March, 1931, Lord Irwin agreed a deal with Gandhi. In exchange for prisoner-release and other concessions, civil disobedience would be halted and Congress would attend the next session of the Round Table Conference. A few hours after the agreement was reached, Gandhi came back to see Irwin. Jawaharlal Nehru had told Gandhi that he "had unwittingly sold India". Irwin later recalled: "I exhorted him not to let this worry him unduly, as I had no doubt that very soon I should be getting cables from England, telling me that in Mr Churchill's opinion I had sold Great Britain."

Ramsay MacDonald, the former leader of the Labour Party, and head of the National Government appointed Lord Irwin as his president of the Board of Education in June 1932. He did not have progressive views on education and is quoted as saying the country needed state schools to "train them up for servants and butlers". In 1933 he was appointed as chancellor of the University of Oxford.

Upon the death of his 94-year-old father in January 1934, became Viscount Halifax. When Stanley Baldwin replaced MacDonald as prime minister in June 1935, Halifax was moved from education to the War Office. He did not seem particularly worried by the emergence of Adolf Hitler and the growth of Nazi Germany and according to his biographer, David Dutton, "at the committee of imperial defence he challenged the assertion of the chiefs of staff that the country's paramount need was to step up the pace of rearmament. It was a weakness in his understanding of the international situation that he never fully grasped, until it was too late, the enormity of Hitler's capacity for evil."

Nancy Astor and her husband, Waldorf Astor held regular weekend parties at their home Cliveden, a large estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames. This group eventually became known as the Cliveden Set. Those who attended included Lord Halifax, Philip Henry Kerr (11th Marquess of Lothian), Geoffrey Dawson, Samuel Hoare, Lionel Curtis, Nevile Henderson, Robert Brand and Edward Algernon Fitzroy. Most members of the group were supporters of a close relationship with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. The group included several influential people. Astor owned The Observer, Dawson was editor of The Times, Hoare was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and Fitzroy was Speaker of the Commons.

Norman Rose, the author of The Cliveden Set (2000): "Lothian, Dawson, Brand, Curtis and the Astors - formed a close-knit band, on intimate terms with each other for most of their adult life. Here indeed was a consortium of like-minded people, actively engaged in public life, close to the inner circles of power, intimate with Cabinet ministers, and who met periodically at Cliveden or at 4 St James Square (or occasionally at other venues). Nor can there be any doubt that, broadly speaking, they supported - with one notable exception - the government's attempts to reach an agreement with Hitler's Germany, or that their opinions, propagated with vigour, were condemned by many as embarrassingly pro-German."

In 1936 Halifax visited Nazi Germany for the first time. Halifax's friend, Henry (Chips) Channon, reported: "He told me he liked all the Nazi leaders, even Goebbels, and he was much impressed, interested and amused by the visit. He thinks the regime absolutely fantastic." Halifax later explained in his autobiography, Fulness of Days (1957): "The advent of Hitler to power in 1933 had coincided with a high tide of wholly irrational pacifist sentiment in Britain, which caused profound damage both at home and abroad. At home it immensely aggravated the difficulty, great in any case as it was bound to be, of bringing the British people to appreciate and face up to the new situation which Hitler was creating; abroad it doubtless served to tempt him and others to suppose that in shaping their policies this country need not be too seriously regarded."

On 17th June, 1936, Claude Cockburn, produced an article called "The Best People's Front" in his anti-fascist newsletter, The Week. He argued that a group that he called the Astor network, were having a strong influence over the foreign policies of the British government. He pointed out that members of this group controlled The Times and The Observer and had attained an "extraordinary position of concentrated power" and had become "one of the most important supports of German influence".

During the weekend of 23rd October 1937, the Astors had thirty people to lunch. This included Geoffrey Dawson (editor of The Times), Nevile Henderson (the recently appointed Ambassador to Berlin), Edward Algernon Fitzroy (Speaker of the Commons), Sir Alexander Cadogan (soon to replace the anti-appeasement Robert Vansittart as Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office), Lord Lothian and Lionel Curtis. They were happy that Neville Chamberlain, a strong supporter of appeasement was now Prime Minister and that this would soon mean promotion for people such as Lothian and Lord Halifax.

According to Norman Rose, Lord Lothian gave a talk on future relations with Adolf Hitler. "He wished to define what Britain would not fight for. Certainly not for the League of Nations, a broken vessel; nor to honour the obligations of others. As he had explained to the Nazi leaders, 'Britain had no primary interests in eastern Europe,' areas that fell within 'Germany's sphere'. To be dragged into a conflict not of Britain's making and not in defence of its vital interests would bedevil relations with the Dominions, fatal for the unity of the Empire. For the Clivedenites, this was always the bottom line... In effect, Lothian was prepared to turn central and eastern Europe over to Germany." Nancy Astor supported Lothian: "In twenty years I've never known Philip to be wrong on foreign politics." Geoffrey Dawson also agreed with Lothian and this was reflected in an editorial in The Times that he wrote a few days later. Lionel Curtis was the only member of this group that had doubts about Lothian's plans.

In November, 1937, Neville Chamberlain, who had replaced Stanley Baldwin as prime minister, sent Lord Halifax to meet Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Goering in Germany. In his diary, Lord Halifax records how he told Hitler: "Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country." This was a reference to the fact that Hitler had banned the Communist Party (KPD) in Germany and placed its leaders in Concentration Camps. Halifax had told Hitler: "On all these matters (Danzig, Austria, Czechoslovakia)..." the British government "were not necessarily concerned to stand for the status quo as today... If reasonable settlements could be reached with... those primarily concerned we certainly had no desire to block."

The story was leaked to the journalist Vladimir Poliakoff. On 13th November 1937 the Evening Standard reported the likely deal between the two countries: "Hitler is ready, if he receives the slightest encouragement, to offer to Great Britain a ten-year truce in the colonial issue... In return... Hitler would expect the British Government to leave him a free hand in Central Europe". On 17th November, Claude Cockburn reported in The Week, that the deal had been first moulded "into usable diplomatic shape" at Cliveden that for years has "exercised so powerful an influence on the course of British policy." He later added that Lord Halifax was "the representative of Cliveden and Printing House Square rather than of more official quarters." The Reynolds News claimed that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was "in protective custody at Cliveden". The Manchester Guardian, The Daily Chronicle and The Tribune reported the story in a similar fashion.

Whereas Lord Halifax supported Chamberlain's appeasement policy, the foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, was highly critical of this way of dealing with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. On 25th February, 1938 Eden resigned over this issue and Lord Halifax became the new foreign secretary. It was claimed that this was a victory for the Cliveden Set. In a speech given in the House of Commons Eden argued: "I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that tmper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world."

Soon after Lord Halifax's appointment, Adolf Hitler invited Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, to meet him at Berchtesgarden. Hitler demanded concessions for the Austrian Nazi Party. Schuschnigg refused and after resigning was replaced by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the leader of the Austrian Nazi Party. On 13th March, Seyss-Inquart invited the German Army to occupy Austria and proclaimed union with Germany.

The union of Germany and Austria (Anschluss) had been specifically forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. Some members of the House of Commons, including Anthony Eden and Winston Churchill, now called on Lord Halifax and Neville Chamberlain to take action against Adolf Hitler and his Nazi government. However, they still retained the support of most of the Conservative Party and Henry (Chips) Channon suggested that the problem was with the rest of the government: "Halifax and Chamberlain are doubtless very great men, who dwarf their colleagues; they are the greatest Englishmen alive, certainly; but aside from them we have a mediocre crew; I fear that England is on the decline, and that we shall dwindle for a generation or so. We are a tired race and our genius seems dead."

Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe, a close friend of Adolf Hitler, asked her friend, Lady Ethel Snowden to arrange a meeting with Lord Halifax, about arranging unofficial talks with the Nazi government. Halifax wrote in his diary on 6th July 1938: "Lady Snowden came to see me early in the morning. She informed me that, through someone on the closest terms with Hitler - I took this to mean Princess Hohenlohe - she had received a message with the following burden: Hitler wanted to find out whether H.M. Government would welcome it if he were to send one of the closest confidants, as I understand it, to England for the purpose of conducting unofficial talks. Lady Snowden gave me to understand that this referred to Field-Marshal Goering, and they wished to find out whether he come come to England without being too severely and publicly insulted, and what attitude H.M. Government would take generally to such a visit."

Lord Halifax was initially suspicious of Princess Stephanie. He had been warned the previous year by Walford Selby, the British ambassador in Vienna, that Stephanie was an "international adventuress" who was "known to be Hitler's agent". He had also heard from another source that she was a "well known adventuress, not to say blackmailer". Despite this, after obtaining permission from Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, he agreed to meet with Hitler's representative, Fritz Wiedemann. The meeting took place on 18th July at Halifax's private residence in Belgravia. Halifax noted in a memorandum: "The Prime Minister and I have thought about the meeting I had with Captain Wiedemann. Of especial importance to us are the steps which the Germans and the British might possibly take, not only to create the best possible relationship between the two countries, but also to calm down the international situation in order to achieve an improvement of general economic and political problems."

Someone leaked the meeting to The Daily Herald. When it appeared in the newspaper on 19th July, it created a storm of controversy. The French government complained that the meeting had been arranged by Princess Holenlohe, who according to their intelligence services was a "Nazi agent". Jan Masryk, the Czech ambassador in London, wrote to his government in Prague on 22nd July: "If there is any decency left in this world, then there will be a big scandal when it is revealed what part was played in Wiedemann's visit by Steffi Hohenlohe, née Richter. This world-renowned secret agent, spy and confidence trickster, who is wholly Jewish, today provides the focus of Hitler's propaganda in London." On 23rd July 1938, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Wiedemann's visit to Halifax on the Führer's instructions continues to dominate the foreign press more than ever."

Walford Selby was also shocked by this meeting that had been arranged by Princess Stephanie. He warned the government that he had information that her suite at the Dorchester Hotel in London had become a base for Nazi sympathisers and an "outpost of German espionage", and that she had been behind much of the German propaganda circulating in London since she first moved to England. On 31st July, The Daily Express published an article about the man who had met Lord Halifax in secret. They described Fritz Wiedemann as Hitler's "listening-post, his contact man, negotiator, a checker-up, a man with a job without a name and without a parallel".

International tension increased when Adolf Hitler began demanding that the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia should be under the control of the German government. In an attempt to to solve the crisis, Lord Halifax and Neville Chamberlain and the heads of the governments of Germany, France and Italy met in Munich. On 29th September, 1938, Chamberlain, Hitler, Edouard Daladier and Benito Mussolini signed the Munich Agreement which transferred to Germany the Sudetenland, a fortified frontier region that contained a large German-speaking population. When Eduard Benes, Czechoslovakia's head of state, who had not been invited to Munich, protested at this decision, Chamberlain told him that Britain would be unwilling to go to war over the issue of the Sudetenland.

The Munich Agreement was popular with most people in Britain because it appeared to have prevented a war with Germany. However, some politicians, including Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, attacked the agreement. These critics pointed out that no only had the British government behaved dishonorably, but it had lost the support of Czech Army, one of the best in Europe.

Halifax also did what he could to persuade the British press not to criticise Adolf Hitler. According to Herbert von Dirksen, the German ambassador to London, he even went to see the cartoonist, David Low: "On his return to England he (Lord Halifax) had done his best to prevent excesses in the Press; he had had discussions with two well-known cartoonists, one of them the notorious Low, and with a number of eminent representatives of the Press, and had tried to bring influence to bear on them. He (Lord Halifax) had been successful up to a point. It was extremely regrettable that numerous lapses were again to be noted in recent months. Lord Halifax promised to do everything possible to prevent such insults to the Führer in the future."

In March, 1939, the German Army seized the rest of Czechoslovakia. In taking this action, Adolf Hitler had broken the Munich Agreement. Lord Halifax and Neville Chamberlain, now realized that Hitler could not be trusted and their appeasement policy now came to an end. However, the British government was slow to react. As Clive Ponting, the author of 1940: Myth and Reality (1990) points out: "Hitler remained obdurate and the British government, under immense pressure from the House of Commons, finally declared war seventy-two hours after the German attack on their ally. Until the summer of 1940 they continued to explore numerous different approaches to see whether peace with Germany was possible. The main advocates of this policy after the outbreak of war were the Foreign Office, in particular its two ministers - Lord Halifax and Rab Butler - together with Neville Chamberlain."

Halifax defended his role in appeasement in in his autobiography, Fulness of Days (1957): "One fact remains dominant and unchallengeable. When war did come a year later it found a country and Commonwealth wholly united within itself, convinced to the foundations of soul and conscience that every conceivable effort had been made to find the way of sparing Europe the ordeal of war, and that no alternative remained. And that was the best thing that Chamberlain did."

After the outbreak of the Second World War Lord Halifax remained as the country's foreign secretary. On 14th December, 1939, Lord Lothian wrote to Halifax: "American opinion is still... almost unanimously anti-Nazi. In addition it is now almost more strongly anti-Soviet. It is to a much less degree pro-French or pro-British. There are formidable elements which are definitely anti-British which take every opportunity to misrepresent our motives and attack our methods.... I have no doubt that the best corrective is the fullest possible publicity from England and France through the important and high class American correspondents of what the Allies are thinking and doing."

When Neville Chamberlain resigned in May, 1940, the new premier, Winston Churchill kept Lord Halifax as foreign secretary in order to give the impression that the British government was united against Adolf Hitler. The following month, Joseph Goebbels recorded in his diary that Hitler had told him that peace negotiations had begun with Britain through Sweden. Three days later, a Swedish banker, Marcus Wallenberg, told British Embassy officials in Stockholm that the Germans were prepared to negotiate - but only with Lord Halifax.

In December, 1940, Lord Halifax was replaced as foreign secretary by his long-term opponent, Anthony Eden. Halifax now became British ambassador to the United States. As Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has pointed out: "Lord Halifax was the six-foot-six-inch, living, breathing personification of every negative stereotype that Americans nurtured with regard to Britain - the very antithesis of the dynamic new nation of Spitfires and the Dunkirk spirit."

In November 1942 Lord Halifax heard that his second son, Peter, had been killed in action in North Africa. Only two months later he learned that his youngest son, Richard, had been severely wounded. Halifax remained a somewhat reluctant ambassador over the following months. At the end of the Second World War he agreed to the request of the new Labour foreign secretary, Ernest Bevin, that he should carry on until May 1946. This extension enabled him to play an important part in the negotiations led by John Maynard Keynes to secure an American loan after the abrupt termination of lend-lease.

On his arrival home he was invited to join Churchill's shadow cabinet, but he declined the offer. However, he continued to play an active role in the House of Lords. He took part in the debate over Indian Independence. Lord Templewood, the former Samuel Hoare, criticizing the decision of the Labour cabinet to hand over India to an Indian government by June 1948 at the latest "without any provision for the protection of minorities or the discharge of their obligations". According to David Dutton, Halifax argued that "he was not prepared to condemn what the government was doing unless he could honestly and confidently recommend a better solution, which he could not".

In his retirement Lord Halifax wrote his memoirs, Fulness of Days (1957) where he attempted to defend the policy of appeasement. Edward Wood, 3rd Viscount Halifax, died at Garroby Hall, near York, on 23rd December, 1959.

Primary Sources

(1) Lord Halifax, Fulness of Days (1957)

The advent of Hitler to power in 1933 had coincided with a high tide of wholly irrational pacifist sentiment in Britain, which caused profound damage both at home and abroad. At home it immensely aggravated the difficulty, great in any case as it was bound to be, of bringing the British people to appreciate and face up to the new situation which Hitler was creating; abroad it doubtless served to tempt him and others to suppose that in shaping their policies this country need not be too seriously regarded.

(2) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (5th December, 1936)

I had a long conversation with Lord Halifax about Germany and his recent visit. He described Hitler's appearance, his khaki shirt, black breeches and patent leather evening shoes. He told me he liked all the Nazi leaders, even Goebbels, and he was much impressed, interested and amused by the visit. He thinks the regime absolutely fantastic, perhaps even too fantastic to be taken seriously. But he is very glad that he went, and thinks good may come of it. I was rivetted by all he said, and reluctant to let him go.

(3) Lord Halifax met Adolf Hitler in Brechtesgaden on 19th November, 1937. He recorded the meeting in his diary.

Hitler invited me to begin our discussion, which I did by thanking him for giving me this opportunity. I hoped it might be the means of creating better understanding between the two countries. The feeling of His Majesty's Government was that it ought to be within our power, if we could once come to a fairly complete appreciation of each other's position, and if we were both prepared to work together for the cause of peace, to make a large contribution to it. Although there was much in the Nazi system that profoundly offended British opinion, I was not blind to what he (Hitler) had done for Germany, and to the achievement from his point of view of keeping Communism out of his country.

(4) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (12th May, 1938)

This Government has never commanded my respect: I support it because the alternative would be infinitely worse. But our record, especially of late, is none too good. Halifax and Chamberlain are doubtless very great men, who dwarf their colleagues; they are the greatest Englishmen alive, certainly; but aside from them we have a mediocre crew; I fear that England is on the decline, and that we shall dwindle for a generation or so. We are a tired race and our genius seems dead.

(5) In March, 1939 Herbert von Dirksen, the German Ambassador in London, sent a telegram to Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Foreign Minister. The telegram commented on the talks between Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Minister, and Joseph Goebbels, the German Minister of Propaganda, that had taken place in Berlin.

On his return to England he (Lord Halifax) had done his best to prevent excesses in the Press; he had had discussions with two well-known cartoonists, one of them the notorious Low, and with a number of eminent representatives of the Press, and had tried to bring influence to bear on them.

He (Lord Halifax) had been successful up to a point. It was extremely regrettable that numerous lapses were again to be noted in recent months. Lord Halifax promised to do everything possible to prevent such insults to the Fuehrer in the future.

(6) In his memoirs Lord Halifax attempted to justify his appeasement policy that culminated in the signing of the Munich Agreement in September, 1938.

The criticism excited by Munich never caused me the least surprise. I should very possibly indeed have been among the critics myself, if I had not happened to be in a position of responsibility. But there were two or three considerations to which those same critics ought to have regard. One was that in criticizing the settlement of Munich, they were criticizing the wrong thing and the the wrong date. They ought to have criticized the failure of successive Governments, and of all parties, to foresee the necessity of rearming in the light of what was going on in Germany; and the right date on which criticism ought to have fastened was 1936, which had seen the German reoccupation of the Rhineland in defiance of treaty provisions.

I have little doubt that if we had then told Hitler bluntly to go back, his power for future and larger mischief would have been broken. But, leaving entirely aside the French, there was no section of British public opinion that would not have been directly opposed to such action in 1936. To go to war with Germany for walking into their own backyard, which was how the British people saw it, at a time moreover when you were actually discussing with them the dates and conditions of their right to resume occupation, was not the sort of thing people could understand. So that moment which, I would guess, offered the last effective chance of securing peace without war, went by.

(7) In his memoirs, Fulness of Days, Lord Halifax loyally defends Neville Chamberlain and the signing of the Munich Agreement in September, 1938.

The other element that gave fuel to the fires of criticism was the unhappy phrases which Neville Chamberlain under the stress of great emotion allowed himself to use. 'Peace with Honour'; 'Peace for our time' - such sentences grated harshly on the ear and thought of even those closest to him. But when all has been said, one fact remains dominant and unchallengeable. When war did come a year later it found a country and Commonwealth wholly united within itself, convinced to the foundations of soul and conscience that every conceivable effort had been made to find the way of sparing Europe the ordeal of war, and that no alternative remained. And that was the best thing that Chamberlain did.

(8) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

Halifax was a man of deep sincerity and pleasing personality. In the Churchill coalition he gave the impression of being a competent statesman though not, perhaps, one destined for immortal fame. Churchill seemed to get on well enough with him, but there was a certain coolness which suggested that he had not entirely forgotten Halifax's connexion with a cabinet which had pursued, in his judgment, wrong policies before and after war broke out. He was one of the men of Munich. It may well be that Churchill included Halifax, as he did Chamberlain, as a deliberate policy of taking some of the prominent supporters of the Baldwin and Chamberlain regimes into his coalition to preserve the unity of his Party.

As Ambassador to the U.S.A., upon ceasing to be Foreign Secretary, Halifax was a conspicuous success. Next to Royalty the citizens of the American republic love an aristocrat as a visitor, official or otherwise. Halifax combined his aristocratic status with a real man-to-man attitude which endeared him to the Administration, to Congressmen, to businessmen, and to the public.

(9) Clive Ponting, 1940: Myth and Reality (1990)

The British government entered the war in September 1939 with a distinct lack of enthusiasm. For two days after the - German invasion of Poland they tried to avoid declaring war. They hoped that if the Germans would agree to withdraw, then a four-power European conference sponsored by Mussolini would be able to devise a settlement at the expense of the Poles. But Hitler remained obdurate and the British government, under immense pressure from the House of Commons, finally declared war seventy-two hours after the German attack on their ally. Until the summer of 1940 they continued to explore numerous different approaches to see whether peace with Germany was possible. The main advocates of this policy after the outbreak of war were the Foreign Office, in particular its two ministers - Lord Halifax and Rab Butler - together with Neville Chamberlain. But the replacement of Chamberlain by Churchill had little effect on this aspect of British policy and the collapse of France forced the government into its most serious and detailed consideration of a possible peace. Even Churchill was prepared to cede part of the Empire to Germany if a reasonable peace was on offer from Hitler. Not until July 1940 did an alternative policy - carrying on the war in the hope that the Americans would rescue Britain - become firmly established.

British peace efforts in the period 1939-40 remain a highly sensitive subject for British governments, even though all the participants are now dead. Persistent diplomatic efforts to reach peace with Germany are not part of the mythology of 1940 and have been eclipsed by the belligerent rhetoric of the period. Any dent in the belief that Britain displayed an uncompromising 'bulldog spirit' throughout 1940 and never considered any possibility other than fighting on to total victory is still regarded as severely damaging to Britain's self-image and the myth of 'Their Finest Hour'. The political memoirs of the participants either carefully avoid the subject or are deliberately misleading. Normally, government papers are available for research after thirty years but some of the most sensitive British files about these peace feelers, including key war cabinet decisions, remain closed until well into the twenty-first century. It is possible, however, to piece together what really happened from a variety of different sources and reveal the reality behind the myth.

(10) Clive Ponting, 1940: Myth and Reality (1990)

The main contacts in the autumn of 1939 were, as in 1940, made through the various neutral countries, which were still able to act as intermediaries between Britain and Germany. Early in October contacts were established with the German ambassador in Ankara, von Papen, but these came to nothing. A more substantial approach was made via the Irish. On 3 October the Irish Foreign Office told the German embassy in Dublin that Chamberlain and those around him wanted peace, provided that British prestige was preserved. This approach was not an Irish initiative but represented a British attempt to explore a possible basis for peace with Germany. The subject is still regarded as highly sensitive and all British files remain closed until 2016. Some evidence of the sort of terms the British may have had in mind is provided by Rab Butler's conversation with the Italian ambassador in London on 13 November. Butler, obviously intending that the message should be passed on to Germany, said that the Germans would not have to withdraw from Poland before negotiations to end the war began. He also made it clear that Churchill, with his more bellicose public utterances, spoke only for himself and did not represent the views of the British government.

The possibility of peace was also high on the agenda in the spring of 1940 before the German attack on Scandinavia. Influential individuals within the British establishment thought peace should be made. When the foremost independent military expert in the country, Sir Basil Liddell-Hart, was asked in early March what he thought Britain should do, he replied: "Come to the best possible terms as soon as possible ... we have no chance of avoiding defeat." Lord Beaverbrook, proprietor of Express Newspapers, was even prepared to back 'peace' candidates run by the Independent Labour Party at by-elections. He offered £500 per candidate and newspaper backing, but the scheme never got off the ground. Within the government there were similar yearnings for peace. On 24 January Halifax and his permanent secretary, Sir Alexander Cadogan, had a long conversation about possible peace terms. Cadogan reported that Halifax was "in a pacifist mood these days. So am I, in that I should like to make peace before war starts." The two men believed that peace was not possible with Hitler on any terms that he would find acceptable and were worried that either the Pope or President Roosevelt might intervene with their own proposals. If they did, then Allied terms would have to be put forward, but neither Halifax nor Cadogan could think what they should be. Cadogan concluded: "We left each other completely puzzled." The British were also under pressure from the dominions to make peace. This was urged by both New Zealand and Australia. The Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, wrote to his High Commissioner in London, Bruce, that Churchill was a menace and a publicity seeker and that Britain, France, Germany and Italy should make peace before real war made the terms too stiff and then combine together against the real enemy: Bolshevism.

(11) Clive Ponting, 1940: Myth and Reality (1990)

The meeting also considered what Britain might have to give up in order to obtain a settlement. There was general agreement that Mussolini would want Gibraltar, Malta and Suez and Chamberlain thought he might well add Somaliland, Kenya and Uganda to the list. It was more difficult to see what might have to be conceded to Hitler. The war cabinet were united in agreeing that Britain could not accept any form of disarmament in a peace settlement but that the return of the former German colonies taken away in the Versailles settlement was acceptable. At one point Halifax asked Churchill directly "whether, if he was satisfied that matters vital to the independence of this country were unaffected, he would be prepared to discuss terms". Churchill's reply shows none of the signs of the determined attitude he displayed in public and the image cultivated after the war. It reveals little difference between his views and those of Halifax, and shows he was prepared to give up parts of the Empire if a peace settlement were possible. He replied to Halifax's query by saying that "he would be thankful to get out of our present difficulties on such terms, provided we retained the essentials and the elements of our vital strength, even at the cost of some cession of territory". Neville Chamberlain's diary records the response in more specific terms than the civil service minutes. He quotes Churchill as saying that "if we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies he would jump at it".

(12) Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince and Stephen Prior, Double Standards (2001)

Two other central figures were Lord Halifax, Foreign Secretary from 1938 until November 1940, and his under-secretary, R. A. (Richard Ausren "Rab") Butler. Halifax, although a minister, was a peer and therefore in the House of Lords, whereas Butler was the Foreign Office's representative in the Commons, so it proved particularly useful for them to work as a team. Both men were staunch supporters of Chamberlain's policies, continuing to explore ways of bringing about peace even after the outbreak of war. Halifax described Churchill and his supporters as "gangsters" - an epithet gleefully seized upon by the Nazi propaganda machine. Halifax not only disliked and distrusted Churchill, but was his chief rival for the job of Prime Minister after Chamberlain's resignation...

In early August 1939 a delegation of seven British businessmen met Goring in order to offer concessions that could prevent the outbreak of hostilities. The existence of this mission has been known for a long time, and largely dismissed - in the words of historian Donald Cameron Watt, writing in 1989 - as being made up of "well-meaning amateurs". The group consisted of Lord Aberconway (then chairman of the shipbuilders John Brown & Co. and Westland Aircraft); Sir Edward Mortimer Mountain (chairman of Eagle Star Insurance, among other companies); Charles E Spencer (chairman of Edison Swan Cables); and the prominent stockbroker Sir Robert Renwick. But in 1999 the last surviving member of the delegation, Lord Aberconway, finally revealed that far from being an ad hoc group, it had been sanctioned by Lord Halifax and very probably by Chamberlain himself. The delegation was acting on behalf of the British government, with the aim of persuading Hitler to make the offer of peace talks, which Chamberlain would argue it was his moral obligation to accept.

(13) Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince and Stephen Prior, Double Standards (2001)

Having been dragged into a war it never wanted, Chamberlain's government now sought a way out of it as soon as was possible without losing face. Although Chamberlain appointed Churchill as First Sea Lord and gave him and his ardent supporter Anthony Eden places in the War Cabinet, these were mere sops to the pro-war elements in the House of Commons. Chamberlain's cabinet remained resolutely composed of appeasers such as Halifax, Hoare and Simon. Astoundingly, on 2 September 1939 - the day before Britain declared war - Hoare told a German journalist: "Although we cannot in the circumstances avoid declaring war, we can always fulfil the letter of a declaration without immediately going all out."

It was the Chamberlain government's undeclared policy to fight a short and strictly limited war with a negotiated peace being made as soon as possible - in other words, the whole campaign would be merely a face-saving exercise. This was the strange nervy period known as the "Phoney War", which lasted from September 1939 until April 1940. While Germany and the Soviet Union looted Poland, Britain and France geared up for military action, training troops and manufacturing weapons. Most of the action at this time took the form of grappling for command of the North Sea, with the RAF bombing German warships and U-boats attacking British vessels...

In 1965, Bjorn Prytz, Swedish Ambassador to London during the Second World War, revealed on Swedish radio that he had discussed the possibility of a negotiated peace between Britain and Germany with the Halifax/Butler team in June 1940. The first meeting with Butler was on 17 June, the day that France surrendered to the Nazis. Butler told Prytz that Churchill was indecisive, and assured him that "no occasion would be missed to reach a compromise peace if reasonable conditions could be obtained". According to Prytz, Butler also said that "diehards like Churchill would not be allowed to pre¬vent Britain making a compromise peace with Germany'. During their meeting, Butler was telephoned by Halifax, who asked him to assure Prvtz that Britain's actions would be guided by 'common sense and not bravado'. After this Prytz sent a telegram to his superiors in Stockholm, the details of which were withheld by the Swedish government from the public until the 1990s 'because of British objections.

It is interesting that when Churchill (not yet Prime Minister) made a vehement attack on Hitler on 19 November 1939 - calculated to anger the dictator and effectively scupper any chance of making peace - Butler hurriedly assured the Italian Ambassador that the speech "was in conflict with the government's views". At this stage at least, Churchill's bellicose attitude was widely seen as an embarrassment and a major stumbling block to peace...

The peace camp was very busy in the early months of the war. Goebbels records in his diary that, in June 1940, Hitler told him that peace negotiations were under way, through Sweden. Three days after Goebbels confided this to his diary, a Swedish hanker named Marcus Wallenberg approached British Embassy officials in Stockholm. He told them that the Germans were prepared to negotiate - but only with Lord Halifax.

.