Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Wilkinson, the daughter of a worker in a textile factory, was born in Manchester on 8th October, 1891. Ellen's parents, Richard Wilkinson and Ellen Wood, were both devout Methodists. She later recalled: "I was utterly bored with religion and sermons... sick of the discussions as to what this or that text meant."

According to Angela Jackson: "Her rebellious tendencies were in evidence even in elementary school and developed alongside a growing moral indignation at the social evils she encountered.... Ellen would accompany him (her father) to lectures on the contemporary debates surrounding evolution, exploring the subject further to reading together.

Ellen was educated at Ardwick School and at the age of eleven won the first of several scholarships. As a result of a series of illnesses, she had been largely educated at home. She later recalled that from this date "I paid for my own education by scholarship until I left university."

In 1906 Ellen won a teaching bursary that meant she could enter the Manchester Day Training College for half a week and she spent the rest of the week teaching at Oswald Road Elementary School.

After a period out of work, Ellen Wilkinson's father became a an insurance clerk. Although her father was a supporter of the Conservative Party, Ellen developed an interest in socialism after reading Merrie England by Robert Blatchford. At the age of sixteen Ellen joined both the Independent Labour Party after hearing a speech made by Kathleen Glasier.

In 1910 Wilkinson became a student at Manchester University where she studied history under Professor George Unwin. Wilkinson was active in the University Socialist Federation where she met Clifford Allen and G.D.H. Cole. Wilkinson became disillusioned with her studies at Manchester and later, when she became involved with the National Council of Labour Colleges, she realised "how little real history" she had been taught at university.

In 1912 became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the following year was recruited as a district organizer. Wilkinson also ran the local branch of the Fabian Society where she arranged for people such as Charlotte Despard, Katharine Glasier and Beatrice Webb to speak in Manchester. A pacifist, Wilkinson supported the Non-Conscription Fellowship during the First World War.

There were very few women trade union officials at this time but in July 1915 she was employed by the National Union of Distributive & Allied Workers (AUCE). Wilkinson, the first woman organizer of the AUCE, was also active in local politics and in 1923 was elected to serve on the Manchester City Council.

In the 1924 General Election she was elected to represent Middlesbrough East. In the House of Commons. Wilkinson became known as Red Ellen (both for the colour of her hair and her politics). Active in the 1926 General Strike, afterwards she was co-author with Frank Horrabin and Raymond Postgate of The Workers History of the Great Strike (1927).

Following the 1929 General Election the Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, appointed Wilkinson as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Health. Wilkinson opposed the National Government formed by MacDonald and as a result lost her seat in the 1931 General Election. During this period she began an extramarital affair with Frank Horrabin.

Wilkinson became close to Stafford Cripps, the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Other members of this group included Aneurin Bevan, Frank Horrabin, Winifred Batho, Frank Wise, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, William Mellor, Barbara Betts and G. D. H. Cole. In 1932 the group established the Socialist League.

While out of the House of Commons Wilkinson wrote two books on politics, Peeps at Politicians (1931) and The Terror in Germany (1933) and a novel, The Division Bell Mystery (1932) and contributed articles to the left-wing feminist journal, Time and Tide.

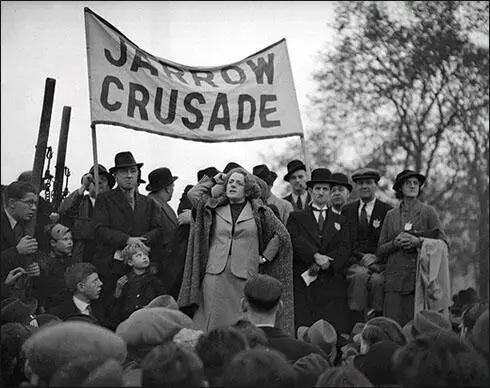

In the 1935 General Election Wilkinson re-entered Parliament as MP for Jarrow. The town had one of the worst unemployment records in Britain. In 1935 nearly 80% of the insured population was out of work. Of the 8,000 skilled manual workers in Jarrow, only 100 were working. In 1936 Wilkinson organised a march of 200 unemployed workers from Jarrow to London where she presented a petition to parliament calling for government action. Wilkinson later wrote an account of the Jarrow Crusade and its outcome called The Town That Was Murdered (1939).

In the 1936 Labour Party Conference, several party members, including Wilkinson, Leah Manning, Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan and Charles Trevelyan, argued that military help should be given to the Spanish Popular Front government, fighting for survival against General Francisco Franco and his right-wing Nationalist Army. Despite a passionate appeal from Senora Isobel de Palencia, the Labour Party supported the Conservative Government's policy of non-intervention.

In December 1936, Wilkinson and Clement Attlee travelled to Spain where they documented the German bombing of Valencia and Madrid and gave support to the Republican forces fighting against General Francisco Franco. On his arrival back home Attlee sent the British Battalion a message: "I would assure the Brigade of my admiration for their courageous devotion to the cause of freedom and social justice. I shall try to tell the comrades at home of what I have seen. Workers of the World unite." Leah Manning commented "henceforth, the No. 1 Company of the Battalion was known as the Major Attlee Company."

In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." William Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Wilkinson, Barbara Betts, Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Harold Laski, Michael Foot, Winifred Batho and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper.

William Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." Stafford Cripps wrote encouragingly after the first issue: "I have read the Tribune, every line of it (including the advertisements!) as objectively as I can and I must congratulate you upon a very first-rate production.''

In May 1937 Wilkinson joined with Charlotte Haldane, Duchess of Atholl, Eleanor Rathbone and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades.

Wilkinson was a strong advocate of Hire Purchase reform. She was concerned about the large number of working-class people who fell into arrears and then lost the goods that they had partly paid for. In 1937 an average of 600 people a day were having high purchase goods seized. These were then sold to the public, providing companies with extra profits. Wilkinson also objected to the high rates of interest being charged on the goods. In 1938 Wilkinson's High Purchase Act became law. The act required traders to display on the goods the actual cash price plus the sum added for interest, and protected hirers who had paid at least one third of the sum contracted.

In the coalition government formed by Winston Churchill in 1940, Wilkinson was appointed parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Pensions. Later she joined the team led by Herbert Morrison at the Home Office. Wilkinson was made responsible for air raid shelters and was instrumental in the introduction of the Morrison Shelters in 1941.

Following the 1945 General Election, the new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Wilkinson as Minister of Education, the first woman in British history to hold the post. Wilkinson's plans to increase the school-leaving age to sixteen had to be abandoned when the government decided that the measure would be too expensive. However, she did managed to persuade Parliament to pass the 1946 School Milk Act that gave free milk to all British schoolchildren.

Ellen Wilkinson, depressed by her failure to bring in all the reforms she believed necessary, took an overdose of barbiturates and died on 6th February, 1947.

Primary Sources

(1) Ellen Wilkinson described her childhood in a radio interview on 27th October, 1945.

My mother had operation after operation. Father had been out of work a long time when I was coming. There was no unemployment benefit or maternity or child welfare schemes. Mother kept going by dressmaking. She couldn't afford proper attendance at my birth and was badly handled. The result was a life of agonizing suffering. But she had the most marvellous recuperative power and would not be an invalid. Once the awful pain was still, she was up and around.

I remember my father speaking bitterly of the life of undernourished idle men, wanting to work, but who were caught up in the realities of the over specialized, under organised cotton trade of pre-war days and of the days when he trampled from one mill to another trying to get a job.

(2) In 1906 Ellen Wilkinson became a teacher at the Oswald Road Elementary School. She recorded her experiences in the classroom in her book Myself When Young (1936)

The boys were filling in time, bored stiff under they reached 14 years and could leave. I was an undersized girl. They all towered above me. My only hope was to interest them sufficiently to keep them reasonably quiet. One day the Headmaster came in and demanded to know why the boys were not sitting upright with their arms folded. "They are sitting that way because I am interesting them" I replied. To which the Headmaster responded by caning almost everyone. We had a grand row, and I was sent home to be reprimanded by an Inspector. But my temper had not calmed. The surging hate of all the silly punishment I had endured in my school days prevented any awe of the Inspector. I whirled all this out at the unfortunate man, who listened quietly and advised: "Don't do any more teaching when you have finished your two years here. Take my advice. Go and be a missionary in China."

(3) At sixteen Ellen Wilkinson was converted to Socialism by reading Merrie England by Robert Blatchford.

It was all very elementary but Blatchford made socialists in those days by the sheer simplicity of his argument. Here was the answer to the chaotic rebellion of my school years. My mother's illness fitted into this protest against the treatment of the sick who could not pay, the inefficiency of commercialism, the waste, the extravagance, and the poverty.

(4) In her book Myself When Young, Wilkinson described hearing Kathleen Glasier speak at an Independent Labour Party meeting in Manchester.

It was a memorable meeting. I got a seat in the front row of the gallery. It seemed noisy to me, whose sole experience of meetings was of religious services. Rows of men filled the platform. But my eyes were riveted on a small slim woman her hair simply coiled into her neck, Katherine Glasier. She was speaking on 'Socialism as a Religion'. To stand on a platform of the Free Trade Hall, to be able to sway a great crowd, to be able to make people work to make life better, to remove slums and underfeeding and misery just because one came and spoke to them about it - that seemed the highest destiny any women could ever hope for.

(5) In her book North Country Born, Sarah Davies described working with Ellen Wilkinson as teenagers in the Independent Labour Party.

For a day's propaganda cycling, we were furnished with sandwiches, a primus stove, stacks of leaflets and The Clarion. We held open-air meetings to catch people as they came out of church or chapel. We scrawled slogans in chalk and we sang England Arise outside pubs and on village greens.

(6) Margery Corbett Ashby commented on the work of Helen Wilkinson in the NUWSS in a letter written on 9th September 1978.

Helen Wilkinson was a first rate organizer who in addition to the necessary virtues of good organizing and eloquent speaking, possessed deep convictions and enthusiasm. To her delightfully warm personality and great charm she added courage in facing hostile audience and wit to deter hecklers.

(7) The Daily Telegraph (12th February, 1925)

Helen Wilkinson, the member for Middlesbrough East has hair of a stunning hue. And this shone like an aureole above the light Botticelli green of her dress. It was a complete breakaway from the sober black and white which earlier lady members adopted. And why not. Is not the Labour Party the party for colour and vivacity.

(8) Ellen Wilkinson, speech in the House of Commons after the passing of the 1928 Equal Franchise Act.

Women have worked hard; starved in prison; given of their time and lives that we might sit in the House of Commons and take part in the legislating of this country.

(9) William Gallacher, The Chosen Few (1940).

Around Easter, 1937, I paid a visit to Spain to see the lads of the British Battalion of the International Brigade. Going up the hillside towards the trenches with Fred Copeman, we could occasionally hear the dull boom of a trench mortar, but more often the eerie whistle of a rifle bullet overhead. Always I felt inclined to get my head down in my shoulders. "I don't like that sound," I said by way of an apology.

"It's all right, Willie, as long as you can hear them,"

I was told. "It's the ones you can't hear that do the damage."

We got into the trenches and I passed along chatting to the boys in the line. From the British we passed into the Spanish trenches and gave the lads there the peoples' front salute. Then, after visiting the American section, we came back to our own lads. All of them came outside and formed a semicircle, and there, with as my background the graves of the boys who had fallen, I made a short speech. It was good to speak under such circumstances, but it was the hardest task I have ever undertaken. When I finished we sang the Internationale with a spirit that all the murderous savagery of fascism can never kill.

The following morning I went into the breakfast room of the Hotel in Madrid to see Herbert Gline, an American working in the Madrid radio station, about a broadcast to America from the Lincoln Battalion. When I got in who should be sitting there but Ellen Wilkinson, Eleanor Rathbone and the Duchess of Atholl. We had a very friendly chat, and I was fortunate in getting their company part of the way home. But whether in Madrid while the shells were falling or in face of the many difficulties that were inseparable from travelling in a country racked with invasion and war, those three women gave an example of courage and endurance that was beyond all praise.

(10) Fred Copeman, was a member of the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about meeting Clement Attlee in his autobiography, Reason in Revolt (1948)

We withdrew to Mondijar, a small village to the east of Madrid. Comfortable quarters in a beautiful countryside soon improved morale. New recruits brought our figure back to the six hundred mark. Field training and manoeuvring took up all our time. During this period Major Attlee, the leader of the British Labour Party, with Ellen Wilkinson and Noel Baker, came out to Spain. Ellen was a great favourite with the lads. Her fiery enthusiasm and kind interest in the smallest things made her the central figure of this group.

At about nine o'clock at night, as darkness was falling, the square at Mondijal was lined by the members of the British 16th and 50th, and the American Washington and Lincoln battalions - some twelve to fifteen hundred men. Those in the rear were holding lighted torches. Clem Attlee and Ellen spoke from a cart, in simple, kind language, of the things that the British Labour Party were trying to do. The response was terriffic. Carried away by the enthusiasm of the speeches, I asked Clem whether he would allow the battalion to be called after him, and he immediately agreed, declaring himself more than honoured. He was to meet considerable opposition on his return to England from the Tory Government over this incident.

(11) Ellen Wilkinson, Sunday Referee (18th October 1936)

Attlee has two fatal handicaps, honesty and modesty, but he is a subtle strategist, understands people and plays with his team. Herbert Morrison is an able administrator and a bit of a brute - the rudest man I know - he will invite you to his table and then read a detective novel but he is giving London almost exclusively gifts needed by the nation.

(12) Emanuel Shinwell was surprised when he heard Clement Attlee had appointed Ellen Wilkinson as Minister of Education.

I mentioned to Attlee that a number of plotters had been given jobs. He laughed, perfectly well aware of what had been going on. It is not bad tactics to make one's enemies one's servants.

(13) Hugh Dalton, diary entry (28th October, 1942)

Ellen Wilkinson to dine with me. This has been on the cards for some time, but always put off. She is still a most devoted worshipper of Herbert Morrison, and puts me second. What she would like would be Morrison to lead the Party and me to be his deputy. She would like us two to go into the War Cabinet, putting out Attlee and Cripps. The difficulty about all such plans is that the right moment never arrives to put them into execution! She says that Morrison, having been deeply absorbed with his job until recently, is now feeling that he has got it into running order, and is taking much more interest in wider questions, including post-war problems and the future of the Labour Party. Bevin, she says - though I think she puts him third in order of merit among Labour leaders - is quite grotesque in his garrulity.

(14) Times Educational Supplement (8th February 1947)

Had Helen Wilkinson lived longer, there is little doubt that the children of England and Wales would have had reason to bless her name. She would have made mistakes; she would have provoked bitter antagonism; but she would have seen to it in fact, as well as promise, no child would be denied the opportunity that was his due.