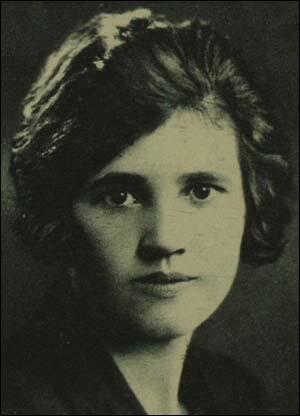

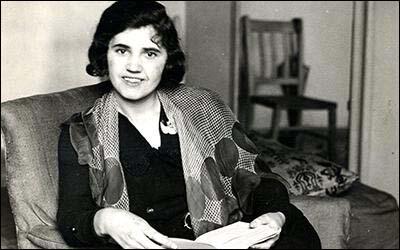

Jennie Lee

Jennie Lee, the daughter of James Lee a miner, was born in Lochgelly, Fife, on 3rd November, 1904.

When Jennie was three years old James and Euphemia were persuaded to take over the management of a hotel and theatre in Cowdenbeath, that had formerly being run by Jennie's grandmother. Trade was affected by the fact that it was a Temperance Hotel and did not sell alcohol.

In 1912 James Lee decided to give up the hotel and once again became a miner. Jennie became a regular visitor to Mr. Garvie's Bookshop in Cowdenbeath. Garvie was blind and used to read to him from his favourite book, A History of the Working Classes. Another family friend, Jim Beveridge, lent Jennie a copy of the Ragged Trousered Philanthropist by Robert Tressell. Jennie Lee was also very fond of the Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde.

James Lee was chairman of the local branch of the Independent Labour Party. Jennie accompanied her father to these meetings and heard several leading socialists including James Maxton and David Kirkwood. Lee like most members of the ILP was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. In the newspapers she read about Aneurin Bevan, a nineteen year old miner from South Wales, who refused to take part in the war. Bevan, who was later to marry Jennie Lee, told the local magistrates: "I am not and never have been a conscientious objector. I will fight, but I will choose my own enemy and my own battlefield and I won't have you do it for me."

As a fourteen year old schoolgirl, Jennie remembered the excitement of her father and friends when they heard news of the Russian Revolution. After the war James Lee was one of the leaders of the Hands off Russia movement that attempted to counterbalance the campaign led by Winston Churchill to invade Russia.

Jennie wanted to go to university but her parents were unable to afford the fees. However, with support from the Carnegie Trust, who agreed to pay half her fees and the Fife Education Authority, who awarded her a grant of £45 a year, she was able to become a student at Edinburgh University.

At university Jennie joined the Labour Club, the University Women's Union and the editorial board of the Rebel Student. One of Jennie's first campaigns was to have Bertrand Russell elected as Rector of the university. Russell a pacifist and campaigner for women's rights was a popular figure with university students at that time. During the First World War Russell was sacked from his post as a lecturer at Cambridge University and imprisoned for his involvement with the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service.

Jennie was a great reader and favourite authors at university included H. N. Brailsford, Bertrand Russell, H. G. Wells and Olive Schreiner. It was while at university in Edinburgh that Jennie gained her first experience of public speaking. Jennie could often be found on the Mound in Princess Street making speeches on Socialism and votes for women on the same terms as men. Jennie also attended weekend schools organised by the National Council of Labour Colleges where she met Ellen Wilkinson for the first time.

During the General Strike Jennie returned home to give support to the miners. She had just won a MacLaren Bursary, which she was able to hand over to her family struggling on her father's strike pay. When the strike was over James Lee, like many union activists, was sacked, blacklisted and after four months unemployment was forced to take work as a manual labourer.

Jennie's political work did not interfere with her studies and she left University of Edinburgh with a degree in education and law. She taught at her school in Cowdenbeath but after an impressive speech at the 1927 National Conference of the Independent Labour Party, Jennie was invited to become the ILP candidate for North Lanarkshire.

Jennie Lee was elected to Parliament at a by-election in February 1929 when she turned a 2,028 Conservative majority into a Labour majority of 6,578. At twenty-four she was the youngest member of the House of Commons. The Labour leadership selected Margaret Bondfield and the Chief Whip, Tom Kennedy, to introduce Jennie into Parliament. Jennie rejected the idea and insisted that two old friends from Scotland, Robert Smillie and James Maxton, should be her sponsors. This was the first of many conflicts that she was to have with the leadership of the party over the next few years.

Jennie's first speech in the House of Commons was a fierce attack on Winston Churchill and his budget proposals. Afterwards she congratulated Jennie on her speech and told her that he also wanted to help the poor but she had to understand that: "The richer the rich became, the more able they would be to help the poor".

In the House of Commons Jennie's closest friend was Frank Wise, one of the leaders of the Independent Labour Party. Wise was married and although he considered the possibility of divorce, they eventually decided against it. As she pointed out in a letter to Wise: "I feel that divorce and marriage would do both of us immense harm. Certainly public non-Catholic opinion is becoming more tolerant about divorce, but in triangles where all three parties are fairly equal as to age and other matters. The situation where a man has lived with one woman for twenty years, and becomes attached to another woman about twenty years younger, is too many unpleasant types, to be lightly accepted."

Another close friend was Aneurin Bevan, who represented Ebbw Vale in South Wales. Jennie was particularly impressed with Bevan's attack on David Lloyd George. The two young MPs had much in common. They both had fathers who were miners who had suffered terrible industrial defeats in 1919, 1921 and 1926. As she wrote later: "We were both now pinning our hopes on political action. We were eager to test to the full the possibility of bringing about basic socialist change by peaceful, constitutional means.

Jennie was totally opposed to Ramsay MacDonald and the National Government he formed in 1931. Like most Labour MPs who refused to support MacDonald, Jennie was defeated in the 1931 General Election. Over the next couple of years Jennie spent her time writing articles for the ILP New Leader and on lecture tours of the United States and Canada.

In 1931 G.D.H. Cole created the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (SSIP). This was later renamed the Socialist League. Other members included William Mellor, Charles Trevelyan, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Gilbert Mitchison, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. Margaret Cole admitted that they got some of the members from the Guild Socialism movement: "Douglas and I recruited personally its first list drawing upon comrades from all stages of our political lives." The first pamphlet published by the SSIP was The Crisis (1931) was written by Cole and Bevin.

According to Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977): "The Socialist League... set up branches, undertook to promote and carry out research, propaganda and discussion, issue pamphlets, reports and books, and organise conferences, meetings, lectures and schools. To this extent it was strongly in the Fabian tradition, and it worked in close conjunction with Cole's other group, the New Fabian Research Bureau." The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies.

In November 1933, Frank Wise collapsed and died. The following year she married Aneurin Bevan. Jennie Lee was defeated again at North Lanark in the 1935 General Election. Jennie remained involved in politics, and was especially active in trying to persuade the British Labour movement to create a Popular Front with other European groups in an attempt to stop the spread of fascism in the 1930s.

In 1940 Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production, employed Jennie Lee in his department. She later left to work as a journalist for the Daily Mirror. In the 1945 General Election, she won the mining constituency of Cannock in Staffordshire. In the government formed by Clement Attlee, Jennie's husband, Aneurin Bevan, was made Minister of Health and was responsible for the introduction of the National Health Service.

Jennie Lee agreed with Aneurin Bevan about most political issues, but was unhappy with his decision to reject unilateral nuclear disarmament at the 1957 Labour Party Conference. However, she was aware that his decision was based on what he thought was best for the Labour movement and was deeply shocked with the way he was treated by fellow socialists during and after his speech. For as he had told her, "I can just about save this Party, but I shall destroy myself in doing so."

After the 1964 General Election Lee was appointed arts minister and was responsible for what Harold Wilson later called the greatest achievement of his Labour Government, the setting up of the Open University. She retired from the House of Commons in 1970 when she was created Baroness Lee of Asheridge.

Jennie Lee died on 16th November 1988.

Primary Sources

(1) In her book My Life with Nye, Jenni Lee wrote an account of life in Cowdenbeath.

My father's favourite bookshop was owned by his blind friend, Mr Garvie, but it was some years before I appreciated the kind of books he stocked. I did get round to it later on. We became good friends. I enjoyed reading to him from A History of the Working Classes Throughout the Ages and listening to what he had to say. He provided the kind of literature the book-hungry activists of the local Labour and Trade Union Movement could find nowhere else.

(2) During the First World War, Jennie's father, James Lee, argued against Britain's involvement in the conflict.

The local ILP, with the redoubtable David Kirkwood from the Clyde as a speaker, decided to hold a "peace by negotiation" meeting outside a military camp in Kinross. There were both soldiers and civilians gathered around their soap-box platform. As soon as my father, who was chairing the meeting, mounted the box, a red-faced, burly figure stalked to the front and literally threw him over the heads of the crowd. David Kirkwood at once jumped on the soap-box and with a voice of thunder shouted, "If there is a better man than me among you, let him come and take this platform." Davie was the hero of the hour: I loved his form of "pacifism". Many ILP members were pacifists, in the strict sense, but others, including my father, took the same stance as a nineteen-year-old South Wales miner, Aneurin Bevan, who, when brought before the local magistrates' court for failing to respond to his call-up papers said, "I am not and never have been a conscientious objector. I will fight, but I will choose my own enemy and my own battlefield and I won't have you do it for me."

(3) Jennie Lee's father was a miner involved in the General Strike.

Although the General Strike lasted only ten days the miners held out from April until December. Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going.

Stanley Baldwin promised that there would be no victimization when the miners went back to work. That was one more piece of deliberate deception. My father was not reinstated - from four months he trudged from pit to pit, turned away everywhere. Uncle Michael was also victimized, and so sadly he came to the decision that the only thing to do was to go off to America.

(4) Jennie Lee worked as a teacher in Cowdenbeath between 1927 and 1929.

Even the poorest parents did everything they possibly could to send their children to school well wrapped up in cold weather and adequately shod, but there were times when at least half a dozen arrived blue with cold and with leaking footwear. Most members of the staff considered themselves a cut above the colliers' children they were teaching and were Conservative in their views, but one thing I did appreciate was the trouble they took to keep a cupboard well stocked with the cast-off clothes and footwear collected from the homes of better-off children.

(5) Fenner Brockway, described Jenni Lee in the 1927 Independent Labour Party Conference in his book Inside the Left.

A young dark girl took the rostrum, a puckish figure with a mop of thick black hair thrown impatiently aside, brown eyes flashing, body and arms moving in rapid gestures, words pouring from her mouth in Scottish accent and vigorous phrases, sometimes with sarcasm which equalled Shinwell's. It was Jennie Lee making her first speech at an ILP conference. And what a speech it was.

(6) Jennie Lee made her first speech in the House of Commons soon after she was elected in a by-election in 1929.

Winston Churchill was at that time Chancellor of the Exchequer and I directed my attack mainly against his budget proposals. Later in the day, in the Smoking Room, he came over to me and congratulated me on my speech. He assured me that we both wanted the same thing, only we had different notions of how to get it. The richer the rich became, the more able they would be to help the poor. That was his theme and he said he would send me a book that would explain everything to me. The book duly arrived. It was The American Omen by Garet Garrett, a right-wing economist who was despised by most of us for his extreme views.

(7) In her book My Life With Nye, Jennie Lee explained how in 1929 Beatrice Webb taught the wives of the newly elected Labour MPs how to behave.

One of my infuriating memories of this time, arising from the greatly varying educational and income standards of Labour Members of Parliament, was Beatrice Webb taking it upon herself to teach the wives of the poorer Labour MPs how to dress, how to curtsey, how to behave generally when invited to Buckingham Palace or any other grand social occasion. I was saddened that our poor women should have been so bamboozled by the Webbs. They had their own natural dignity, their own best clothes for special occasions. But these things Mrs. Webb did not understand.

(8) In her book My Life With Nye, Jennie Lee described meeting H. G. Wells at a dinner party in 1929.

H. G. Wells was one of the bright guiding stars of my youth. I read avidly everything he wrote. That day in Parliament there had been a violent debate about all the issues that meant most to me - the cruelty and indignities of the Means Test, failure to get on with the building of urgently needed houses, schools and hospitals, and all this against a background of hundreds of thousands of unemployed building workers. I arrived at Great College Street brimming over with indignation. H. G. Wells brushed aside anything I tried to say, returning obsessively to the teaching of history in schools. We began glaring at one another with growing hostility. So this was H. G. Wells, this dumpy little man with the squeaky voice, totally indifferent to the problems that concerned the great mass of ordinary people.

(9) Lord Beaverbrook sent a message to a friend on Jennie Lee.

She is pretty. She has brains. She follows Maxton, quarrels with the Labour Party, hates MacDonald; loathes Snowden; loves Russia.

(10) Milovan Djilas, Rise and Fall (1985)

Bevan and Jennie Lee stayed with us in Belgrade for a day or two. Plump, with a florid face and light blue "Welsh" eyes, prematurely gray, Bevan expounded his views slowly and patiently. But along with that went an inquiring mind, quick response, and sparkling wit. The qualities I most liked in him were the unconventionality of his sharp intelligence and a faith in socialism that was that of a man of the people, primordial, unshakable.

Between Bevan and me there was a curious affinity in our perception of the crisis into which both variants of socialism, Western and Eastern, were plunging. We both believed in moral boundaries in politics, though politics as such neither can nor need be moral. Those boundaries do not coincide with the striving for truth, but they are not totally distinct from it either. The later conjectures and charges that Bevan influenced me are untrue. Those charges were officially denied in Tito's letter to Bevan after accounts with me had been settled.

To the end, Bevan and Jennie Lee stubbornly protested against the pressures brought to bear on me, and he turned for help to the Socialist International. His death in 1960, while I was in prison, hit me like the loss of a very close friend. Other friends had long since abandoned me, and I had been anathematized by many. With me, affinities in viewpoint always blend with personal affection. When I first left prison, I dedicated my book Conversations with Stalin to Bevan, repaying as best I could the debt I owed this faithful and constant fighter.

Jennie Lee differed from her husband, not so much in the principles she stood for as in her way of interpreting them. More reserved, not as rhetorical, she was sharper and harder than her husband, who in his early youth had been a miner, whereas she had had a university education. For her, principles were the main thing; for him, testing them was equally important.

Jennie Lee came twice to Belgrade on my account, first when I was arrested in 1956 and again when I was released in 1961. The 1956 trip was without question a solace to Stefica and our small circle of sympathizers, but its impact on officials was probably limited to their meting out a "gentler" penalty. Her second trip reinforced our friendship and brought sad memories of Aneurin. We have continued corresponding - infrequently but warmly - to this day. When Stefica and I visited London in 1969, we were in effect guests of hers and under her constant care.

(11) Jennie Lee, Tomorrow is a New Day (1939)

Aneurin and I were at the cottage that Sunday in September when war was declared. We tuned into the one o'clock news for official confirmation that the fight had really begun. We had discussed all this so often and so much. Now at last it had come. Our enemy Hitler had become the national enemy. All those who hated fascism would have their chance to fight back. No more one-sided massing of all the wealth, influence and arms of international reaction against the workers of first one country then another. I thought of Spain. I had a guilty feeling about Spain. I said something to Aneurin that must have indicated the drift of my thoughts. He had been pacing up and down our long, low, white-washed cottage room, for once too excited for words. He stopped walking up and down to rummage in a corner among a disorderly pile of gramophone records. He found what he was looking for. He found records we had not dared to play for more than a year: the marching songs of the Spanish Republican armies.