The Socialist League

On 24th August 1931, Ramsay MacDonald formed a National Government. Only three members of the Labour administration, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the government. Other appointments included Stanley Baldwin (Lord President of the Council), Neville Chamberlain (Health), Samuel Hoare (Secretary of State for India), Herbert Samuel (Home Office), Philip Cunliffe-Lister (Board of Trade) and Lord Reading (Foreign Office).

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures. (1)

The cuts in public expenditure did not satisfy the markets. The withdrawals of gold and foreign exchange continued. On September 16th, the Bank of England lost £5 million; on the 17th, £10 million; and on the 18th, nearly £18 million. On the 20th September, the Cabinet agreed to leave the Gold Standard, something that John Maynard Keynes had advised the government to do on 5th August.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly." (2)

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Charles Trevelyan, Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Jennie Lee, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, and Margaret Bondfield lost their seats.

Formation of the Socialist League

After the election most members of the Labour Party rejected the gradualist doctrines of the MacDonald leadership. In the 1920s MacDonald had argued that socialism "would evolve from capitalism as the oak from the acorn". This view was now totally discredited. Capitalism had plunged the working class into mass unemployment and the MacDonald government had demanded cuts in the standard of living of workers. Most members, including those on the right of the party, had concluded that henceforth the only way forward was the "decisive transformation to socialism". (3)

The Independent Labour Party, the main left-wing pressure group in the Labour Party, decided to disaffiliate from the Party. It was replaced by another left-wing pressure group, the Socialist League. Members included G.D.H. Cole, William Mellor, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. J. T. Murphy became its secretary. Murphy saw the Socialist League as "the organization of revolutionary socialists who are an integral part of the Labour movement for the purpose of winning it completely for revolutionary socialism". (4)

George Lansbury, the new left-wing leader of the Labour Party, was sympathetic to the ideas of the Socialist League and it was no surprise that at the 1932 Labour Conference agreed that once in power they would take all banks into public ownership on the grounds that control of them would be essential for real socialist planning. Another successful Socialist League resolution laid down "that the leaders of the next Labour Government and the Parliamentary Labour Party be instructed by the National Conference that, on assuming office... definite Socialist legislation must be immediately promulgated... we must have Socialism in deed as well as in words". (5)

A. J. A. Morris, pointed out that the wealthy Charles Trevelyan, the first of MacDonald's ministers to resign over his right-wing policies, helped to fund the group. "Trevelyan... encouraged the Socialist League, gave help both political and material to a number of aspiring and established left-wingers, and seemed quite convinced that the Labour Party was at last committed to socialism. There was a brief moment of personal triumph at the annual party conference in 1933. He successfully introduced a resolution that, if there were even a threat of war, the Labour Party would call a general strike." (6)

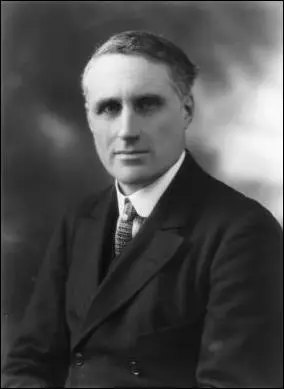

Charles Trevelyan

According to Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977): "The Socialist League... set up branches, undertook to promote and carry out research, propaganda and discussion, issue pamphlets, reports and books, and organise conferences, meetings, lectures and schools. To this extent it was strongly in the Fabian tradition, and it worked in close conjunction with Cole's other group, the New Fabian Research Bureau." The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies. (7)

G.D.H. Cole arranged for Ernest Bevin to be elected chairman of the Socialist League. However, the following year, the Independent Labour Party members insisted on Frank Wise becoming chairman. Cole wrote later, "as the outstanding Trade Union figure capable of rallying Trade Union opinion behind it I voted against... but I was outvoted and agreed to go with the majority". Cole attempted to persuade Bevin to join the Socialist League Executive, but he refused: "I do not believe the Socialist League will change very much from the old ILP attitude, whoever is in the Executive."

Gilbert Mitchison, a member of the Socialist League, published a much-discussed book, The First Workers' Government (1934), advocating an enabling act under which a future Labour government would nationalize most of the economy and redistribute wealth, bringing in socialism almost overnight. Clement Attlee, another member of the Socialist League, wrote at this time: "The moment to strike is the moment of taking power when the Government is freshly elected and assured of its support. The blow struck must be a fatal one and not merely designed to wound and to turn a sullen and obstructive opponent into an active and deadly enemy." (8)

Ben Pimlott argues that G.D.H. Cole was the main figure in the Socialist League. "The Socialist League was socialist first and radical second; like the ILP and the CP its approach was fundamentally utopian... In this respect Cole, the effective founder of Guild Socialism, was the major figure. In spite of his tactical differences with the League, his intellectual influence remained strong. He played a large part in the formulation of the League's policy document, Forward to Socialism ; he continued to deliver lectures to, and write pamphlets for, the League; and several of his former SSIP colleagues remained on the National Council. " Cole used his position to promote the idea of workers' control of industry. (9)

Left Book Club

In May 1936, the Left Book Club was formed. It's monthly offerings, selected by Victor Gollancz, John Strachey and Harold Laski, became highly successful. The main aim was to spread socialist ideas and to resist the rise of fascism in Britain. Gollancz announced: "The aim of the Left Book Club is a simple one. It is to help in the terribly urgent struggle for world peace and against fascism, by giving, to all who are willing to take part in that struggle, such knowledge as will immensely increase their efficiency." (10)

As Ruth Dudley Edwards, the author of Victor Gollancz: A Biography (1987), pointed out: "They were a formidable trio: Laski the academic theoretician; Strachey the gifted popularizer; and Victor the inspired publicist. All three had known a lifelong passion for politics and all had swung violently left in the early 1930s. Only Victor did not describe himself as completely Marxist, though he was objectively indistinguishable from the real article." (11)

Within a short period the Left Book Club achieved a membership of nearly 60,000 and had some 1,200 local discussion groups linked by a monthly bulletin, Left News. "In addition, there were functional groups for scientists, doctors, engineers, lawyers, teachers, civil servants, poets, writers, artists, musicians and actors; and the Club was also responsible for the arrangement of rallies, meetings, lectures, weekend and vacation schools." (12)

Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977) has argued: "The growth of the Club was partly spontaneous, partly a consequence of imaginative organization From the start, giant Club rallies were held in large halls all over the country. In attendance and in drama, the Club's biggest meetings outdid any organized by the Labour Party. People came to a Club rally as to a revivalist meeting, to hear the best orators of the far left - Laski, Strachey, Pollitt, Gallacher, Ellen Wilkinson, Pritt, Bevan, Strauss, Cripps, plus the occasional non-socialist, such as the Liberal, Richard Acland." (13)

After the success of the Left Book Club members of the left-wing of the Labour Party began to believe there was a market for a socialist weekly newspaper. In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." William Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Barbara Betts, Konni Zilliacus, Harold Laski, Michael Foot and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper. Winifred Batho reviewed films and books for the journal. Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it."

Clement Attlee and the Socialist League

Clement Attlee replaced George Lansbury as leader of the Labour Party. Attlee now left the Socialist League and began to move the party to the right. In 1936 Hugh Dalton became Chairman of the Labour Party National Executive, and Ernest Bevin, another former member of the League, became Chairman of the General Council of the Trade Union Congress. They were now in a position to oppose left-wing policies that were favoured by its membership. (14)

Attlee first decided to tackle the Labour League of Youth, who he believed was under the control of the Socialist League. In an investigation carried out in 1936 it claimed that "the real object of the League is to enroll large numbers of young people, and by a social life of its own, provide opportunities for young people to study Party Policy and to give loyal support to the Party of which they are members." The Executive decided to remove the right of the Labour League of Youth to be involved in policy decisions. (15)

In 1936 the Conservative government in Britain feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Clement Attlee, Philip Noel-Baker and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be." Cole and Jack Murphy, the General Secretary of the Socialist League also called for help to be given to the Popular Front government. (16)

United Front

In the early days of the Socialist League G.D.H. Cole, R. H. Tawney and Frank Wise, signed a letter urging the Labour Party to form a United Front against fascism, with political groups such as the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). However, the idea was also rejected when it was proposed at the Labour Party Conference. Although disappointed, the Socialist League issued a statement in June 1935 that it would not become involved in activities definitely condemned by the Labour Party which will jeopardise our affiliation and influence within the Party."

Stafford Cripps was another strong advocate for an United Front: "Up till recent times it was the avowed object of the Communist Party to discredit and destroy the social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party, and so long as that policy remained in force, it was impossible to contemplate any real unity... The Communists had... disavowed any intention, for the present, of acting in opposition to the Labour Movement in the country, and certainly their action in many constituences during the last election gives earnest of their disavowal." (17)

In 1936 the Socialist League joined forces with the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Independent Labour Party and various trades councils and trade union brances to organize a large-scale Hunger March. Aneurin Bevan argued: "Why should a first-class piece of work like the Hunger March have been left to the initiative of unofficial members of the Party, and to the Communists and the ILP... Consider what a mighty response the workers would have made if the whole machinery of the Labour Movement had been mobilised for the Hunger March and its attendant activities." (18)

On 31st October, 1936 the Socialist League called an anti-fascist conference in Whitechapel and discussed the best ways of dealing with Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. Over the next few months several meetings were held. The Socialist League was represented by Stafford Cripps and William Mellor, the Communist Party of Great Britain by Harry Pollitt and Palme Dutt and the Independent Labour Party by James Maxton and Fenner Brockway.

Stafford Cripps continued to argue for the United Front: "The Communist Party and the ILP may not represent very large numbers, but all of us who have knowledge of militant working-class activities throughout the country are bound to admit that Communists and ILPers have played and are playing a very fine part in such activities... Just as unity has wrought wonders in Spain, inspiring and encouraging the Spanish workers with a heroism past all praise, so in our, as yet, less arduous struggle it can give new life and vitality."

Richard Crossman disagreed with Cripps and his followers: "The Socialist League... dilate on the need for Communist affiliation and a strong policy with regard to Spain, as though these items were of the slightest interest to any save the minority of politically conscious electors. Such critics frame their propaganda to satisfy their own tastes and neglect the simple fact that it is not they but the Tory voters who must be converted. Their busy activity is self-intoxicating, but millions of people still read the racing page, because, on the whole, conditions are not bad enough to drive them to politics, and they have not seen a Labour canvasser for five years, far less seen any signs of practical activity by the local Labour Party." (19)

Expulsion of the Socialist League

The United Front agreement won only narrow majority at a Socialist League delegate conference in January, 1937 - 56 in favour, 38 against, with 23 abstentions. The United Front campaign opened officially with a large meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 24th January. Soon afterwards the National Executive of the Labour Party began to discuss what they were going to do about the Socialist League.

On 27th January, 1937, the Labour Party decided to disaffiliate the Socialist League. They also began considering expelling members of the League. G.D.H. Cole and George Lansbury responded by urging the party not to start a "heresy hunt". Arthur Greenwood was one of those who argued that the rebel leader, Stafford Cripps, should be immediately expelled. Cripps was expelled by the National Executive Committee by eighteen to one. He was followed by Charles Trevelyan, Aneurin Bevan and George Strauss in February. (20)

Clement Attlee explained his actions to Harold Laski: "This is the real folly, due, I fear, to a lack of understanding of the movement... The real difficulty will be in meeting the argument that the offenders against party discipline are prominent and for the most part middle-class people and that they should not be treated differently from rank-and-file members who offend and are dealt with by their local parties for infractions of discipline. I fight all the time against heresy hunting, but the heretics seem to seek martyrdom." (21)

The actions of Attlee upset many people in the Labour Party. H. N. Brailsford wrote at the time: "The Labour Party has ceased to be the natural vehicle for the emotions and aspirations of the masses - their anger, their hope, their impulses of humanity and gallantry. It tends to become a mere electioneering machine. My case is, in a sentence, that this jealous boycott of the Left impoverishes and narrows the Party." (22)

On 24th March, 1937, the National Executive Committee declared that members of the Socialist League would be ineligible for Labour Party membership from 1st June. Over the next few weeks membership fell from 3,000 to 1,600. In May, G.D.H. Cole and other leading members decided to dissolve the Socialist League. Later that year at the annual Labour Party Conference, Attlee with the support of the Trade Union blockvote organized by Ernest Bevin, managed to defeat attempts to reinstate the United Front rebels by 1,730,000 votes to 373,000. (23)

.

Primary Sources

(1) Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left (1977)

The Socialist League was socialist first and radical second; like the ILP and the CP its approach was fundamentally utopian. It accepted as an article of faith that unemployment was an endemic feature of capitalism. William Mellor prefaced his proposals for a short-term programme by means of which Labour could tackle unemployment with the note: "The plans out-lined are not presented as a cure of this scourge of capitalism. Socialism alone can change compulsory Unemployment into remunerated leisure, with the machine as a servant, and effective demand equal to productive capacity." Thus non-socialist planning could at best - when carried out by a Labour Government with genuine socialist intentions - bring a temporary alleviation, pending the transition to socialism. At worst, when carried out by a capitalist government, it reinforced the control of industry by capitalist and financial interests, at the expense of the workers.

The latter possibility was especially abhorrent because of the strong Guild Socialist background of the League. In this respect Cole, the effective founder of Guild Socialism, was the major figure. In spite of his tactical differences with the League, his intellectual influence remained strong. He played a large part in the formulation of the League's policy document, Forward to Socialism ; he continued to deliver lectures to, and write pamphlets for, the League; and several of his former SSIP colleagues remained on the National Council. Two of these, Mellor and Horrabin, central figures in the League, had a particularly strong Guild Socialist background. Both had been members of the Labour Research Department group of Guild Socialists with Cole in the early twenties. Mellor had been a Guild Socialist delegate at the Foundation Conference of the CPGB. It was therefore not surprising that the Socialist League put a very strong emphasis on workers' control, or that it put up an intense resistance to any scheme for industry which seemed to negate it.

(2) Gilbert Mitchison, Socialist Leaguer (November, 1934)

Socialists must see that, if industry has to be managed by Boards, the workers have a controlling place on those Boards, both nationally and locally and in every factory or other unit of industry or trade. It is not in practice sufficient that the workers' interests should be represented by one or two trade union officials on a central body. The national or local board must be built up out of similar boards in factories, mines and workshops. It is not impossible to devise means for the election by the workers of their representatives in the control of industry... Nationally, the Board of an industry must be under the direct control of some such planning authoriry as the economic committee of a reconstituted cabiner, and it must be answerable to Parliament.

(3) Stafford Cripps, Socialist Leaguer (July, 1935)

Fundamentally our problem is a simple one. We loathe and detest the whole idea of Imperialism, its fierce competition built upon the greed of capitalism, its exploitation of subject peoples and its selfish approach to all problems of foreign policy. Whether the imperialism is British, French, German, Italian or Japanese, it is equally wrong and equally certain in the long run to plunge the world into war.

(4) Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left (1977)

At the Edinburgh Party Conference in 1936, the League both made ground and lost it. On rearmament, a confused debate in effect left the matter open, and paved the way for a coup by Dalton on the issue in the Parliamentary Party in July 1937. On Spain, an initial resolution backed by the National Council of Labour supporting non-intervention was withdrawn, after Spanish fraternal delegates had made an impassioned plea for aid. A new resolution was presented, demanding that the British and French governments should sell arms to the Spanish Government if other powers could be shown to be violating the Non-Intervention Pact. On Cripps' motion, this was strengthened with a phrase placing on record the Conference's view that the Fascist powers had already violated the Pact, and the whole resolution was carried unanimously.

Thus by the autumn of 1936 the Socialist League had some reason for encouragement, but at the same time the Party's attitude to rearmament was causing concern. Meanwhile, the Left felt its own impotence when it com¬pared its position with that of French and Spanish comrades. Reports from members of the international Brigade, in particular, appeared to present a shining example of the possibilities open to socialists ifthey were able to forget their differences and act together in the struggle against fascism.

After the decision in November 1934 to become a "mass organisation", the Socialist League embarked on a programme of demonstrations and agitation. The results were disappointing. New recruits on the Left went to the Communists. The Socialist League, like the ILP, was outflanked and ignored. This was in spite of the League's new General Secretary, J. T. Murphy, whose energy and enthusiasm were combined with a solid training in the organisational techniques of the CP. Murphy tried to create the atmosphere of a fighting unit, advancing with marxist commitment and determination towards its goal. He made strenuous efforts to tighten organisation by bringing Area Committees and branches more under the direction of the Executive. But it was a losing battle.

The November 1934 Conference had optimistically halved the subscription, in the belief that a consequential increase in working-class membership would more than compensate for the loss of revenue. It did not do so. A permanent deficit necessitated heavy dependence on the munificence of Sir Stafford Cripps.

(5) Stafford Cripps, The Socialist (March, 1936)

Up till recent times it was the avowed object of the Communist Party to discredit and destroy the social democratic parties such as the British Labour Party, and so long as that policy remained in force, it was impossible to contemplate any real unity... The Communists had... disavowed any intention, for the present, of acting in opposition to the Labour Movement in the country, and certainly their action in many constituences during the last election gives earnest of their disavowal.

(6) Aneurin Bevan, News Chronicle (14th September, 1936)

It is of paramount importance that our immediate efforts and energies should be directed to organising a United Front and a definite programme of action.

(7) Aneurin Bevan, The Socialist (November, 1936)

Why should a first-class piece of work like the Hunger March have been left to the initiative of unofficial members of the Party, and to the Communists and the ILP... Consider what a mighty response the workers would have made if the whole machinery of the Labour Movement had been mobilised for the Hunger March and its attendant activities.

(8) Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left (1977)

According to the eventual agreement, the objective of the Unity Campaign was "unity of all sections of the working-class movement within the framework of the Labour Party and Trade Unions in common struggle against Fascism, Reaction and War, and for the immediate demands of the worker, in order to develop the strength and unity of the working-class for the defeat of the National Government". This was to be "built upon the basis of day to day struggle for immediate limited objectives by mass action, industrial and political, and through the democratisation of the Labour Party and Trade Union Movement."

Only the Socialist League, and particularly the undevious Cripps, had accepted this objective as it was stated. The CP's aim was to further its own campaign to affiliate to the Labour Party - or at least to win sympathy inside the Labour Party through its attempt to do so. The ILP joined partly to end its own debilitating isolation and partly as a matter of principle. Maxton, who was opposed to the reaffiliation of the ILP, was highly sceptical about the whole operation. Brockway, though he had come to the conclusion that the ILP must reaffiliate or fade away, later justified his support for the Campaign entirely negatively. Acknowledging that the Campaign was a disastrous failure, he asserted that "if I am asked whether the ILP made a mistake in entering the campaign, my answer is No. The effect would have been disastrous if we had refused the invitation of the Socialist League to participate in an effort to realise what was in the heart of every class-conscious worker - the need for the unity of the working-class."

(9) Stafford Cripps, The Tribune (1st January, 1937)

The Communist Party and the ILP may not represent very large numbers, but all of us who have knowledge of militant working-class activities throughout the country are bound to admit that Communists and ILPers have played and are playing a very fine part in such activities... Just as unity has wrought wonders in Spain, inspiring and encouraging the Spanish workers with a heroism past all praise, so in our, as yet, less arduous struggle it can give new life and vitality.

(10) Clement Attlee, letter to Harold Laski (22nd February, 1937)

This is the real folly, due, I fear, to a lack of understanding of the movement... The real difficulty will be in meeting the argument that the offenders against party discipline are prominent and for the most part middle-class people and that they should not be treated differently from rank-and-file members who offend and are dealt with by their local parties for infractions of discipline. I fight all the time against heresy hunting, but the heretics seem to seek martyrdom.

(11) H. N. Brailsford, The Reynolds' News (24th February, 1937)

The Labour Party has ceased to be the natural vehicle for the emotions and aspirations of the masses - their anger, their hope, their impulses of humanity and gallantry. It tends to become a mere electioneering machine. My case is, in a sentence, that this jealous boycott of the Left impoverishes and narrows the Party.

(12) Richard Crossman, New Statesman (22nd May, 1937)

The Socialist League... dilate on the need for Communist affiliation and a strong policy with regard to Spain, as though these items were of the slightest interest to any save the minority of politically conscious electors. Such critics frame their propaganda to satisfy their own tastes and neglect the simple fact that it is not they but the Tory voters who must be converted. Their busy activity is self-intoxicating, but millions of people still read the racing page, because, on the whole, conditions are not bad enough to drive them to politics, and they have not seen a Labour canvasser for five years, far less seen any signs of practical activity by the local Labour Party.