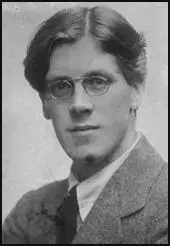

Fenner Brockway

Archibald Fenner Brockway, the only son and eldest of three children of the son of Revd William George Brockway, London Missionary Society missionary, and his wife, Frances Elizabeth Brockway, was born on 1st November, 1888. His mother died when he was fourteen. He was educated at the School for the Sons of Missionaries at Blackheath. (1)

After leaving school he became a journalist. His first job was as a junior on the Examiner, the organ of the Congregationalist. This was followed by becoming sub-editor of the Christian Commonwealth. (2) In 1905 Brockway worked for the Liberal Party candidates for the London County Council elections. (3)

Brockway also began to read the work of left-wing writers such as William Morris, Robert Blatchford, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells and Edward Carpenter. He also found work on the Daily News and in 1907 he was sent to interview James Keir Hardie. Brockway spent an hour listening to Hardie's views on a wide range of different subjects including his experiences as a child working in a colliery. He later recalled that he went to Hardie "as a Young Liberal and left him a Young Socialist". (4)

Brockway joined the Social Democratic Federation, but left after a few months as a result of hearing a speech made by one of its leaders, Harry Quelch. "The contrast between him and my recollection of Hardie decided me. The speech was not as scurrilous as I took it to be, but it was a shock to my youthful idealism and, disillusioned, I handed in my membership card." (5)

Brockway became a socialist and joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and by 1912 was editor of its newspaper, The Labour Leader. (6) At this time Brockway met Lilla Harvey-Smith, a fellow member of the ILP. Lilla was active in the struggle for women's suffrage. After leaving college she worked as a Elementary School Teacher. She was living with her brother, Harry Harvey-Smith and two of her unmarried sisters, Violet and Daisy, at 60 Myddleton Square, London. (7)

Fenner Brockway joined Lilla in the campaign for women's suffrage. Lilla was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and as Brockway pointed out in his autobiography, Inside the Left (1942): "The women's suffrage movement still had my enthusiasm hardly less than the Socialist movement. When the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies threw in its lot with the Labour Party, and particularly with the ILP, I spoke at their meetings frequently and took part in a number of their by-election campaigns." (8)

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This Women Social & Political Union took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (9)

Fenner Brockway & the No-Conscription Fellowship

On 20th August 1914, Fenner Brockway married Lilla Harvey-Smith. (10) They were both opposed to the First World War and over the first few weeks of the conflict exchanged letters through Sweden with Rosa Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin and Karl Liebknecht where they discussed the failure of the Second International to prevent a European war. (11)

Brockway feared the introduction of conscription. Lila Brockway suggested that a letter should be published in the newspaper suggesting an organisation that was opposed to conscription. On 12 November 1914 a letter appeared in the Labour Leader: "Although conscription may not be so imminent as the Press suggests, it would perhaps be well for men of enlistment age who are not prepared to take the part of a combatant in the war, whatever be the penalty for refusing to band themselves together as we may know our strength. As a preliminary, if men between the years of 18 and 38 who take this view will send their names and addresses to me at the addresses given below a useful record will be at our service." (12)

There was a great response to the letter and 150 people joined the organisation, the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) in the first six days. (13) A follow-up letter was published on 3rd December: "Whilst there may not be any immediate danger of conscription, nothing is more uncertain than the duration and development of the war, and it would, we think, be as well of men of enlistment age (19 to 38) who are not prepared to take a combatant's part, whatever the penalty for refusing, formed an organisation for mutual counsel and action. Already, in response to personal appeals, a large number of names have been forwarded for registration, and many correspondents have expressed a desire for knowledge of, and fellowship with others who have come to the same determination not to fight. To meet these needs 'The No-Conscription Fellowship' has been formed, and we invite men of recruitment age who have decided to refuse to take up arms to join. (14)

Lilla Brockway became the honorary Secretary of the NCF, until early in 1915 when an office was opened in London to handle the growing membership. (15) By October 1915 it claimed 5,000 members. (16) Members of the NCF included Clifford Allen, Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Duncan Grant, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, Ramsay MacDonald, Rev. John Clifford, Helena Swanwick, Catherine Marshall, Kathleen Courtney, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Catherine Marshall, Alfred Mason, Winnie Mason, Alice Wheeldon, William Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Hettie Wheeldon, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, and Max Plowman. (17)

Fenner Brockway came under a lot of pressure as editor of The Labour Leader. Soon after the outbreak of the war the newspaper published a peace manifesto from the Independent Socialist Party (USPD), the authorities decided to intervene and closed it down. The evidence against them was unconvincing, the charges were withdrawn and within four weeks it was on the streets again. (18)

The woman's movement was divided about how they should respond to the war. Lilla Brockway, Helena Swanwick, Catherine Marshall, Kathleen Courtney, Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper were totally opposed to the war. The main supporter in the NUWSS was Eleanor Rathbone. Brockway spoke on the subject at the NUWSS at Buxton. "The Conference was the scene of a split. A number of its ablest leaders, including Catherine Marshall, its Parliamentary Secretary, Mrs. H. M. Swanwick, and Miss Courtney, argued that the philosophical basis of the women's movement impelled it to oppose the physical violence of war. The leading spokesman of the opposite view was Eleanor Rathbone... I spoke on the pacifist side and Miss Rathbone used this to prove that sex was not the dividing line between patriotism and pacifism. She insisted that if women gave themselves wholly to the nation in its time of peril they would win the right to political freedom." (19)

Clifford Allen, the manager of the first Labour Party daily newspaper, the Daily Citizen, and the author of the pamphlet, Is Germany Right and England Wrong? (1914) where he argued against Britain becoming involved in an European war, became Chairman of the NCF. "We have got to face the only possible outcome of our Socialist faith - I mean the question of non-resistance to armed force. Don't let us deceive ourselves. The sacredness of human life is the mainspring of all our propaganda. In my opinion there can be no two kinds of murder." (20) Allen was elected as chairman of the NCF and Brockway became secretary of the organisation. (21)

Allen explained the purpose of the No-Conscription Fellowship: "As soon as the danger of conscription became imminent, and the Fellowship something more than an informal gathering, it was necessary for those responsible to consider what should be the basis upon which the organization should be built. The conscription controversy has been waged by many people who, by reason of age or sex, would never be subject to the provisions of a Conscription Act. The chief characteristic of the Fellowship is that full membership is strictly confined to those men who would be subject to the provisions of any such Act." (22)

Brockway developed a good relationship with Allen: "I was fascinated by Allen. In physique he was frail and his charm had an almost feminine quality, but never had I met a man with a keener brain, or more confident decision. He was tall, slight and bent of shoulder; his features were clear-cut and classic, but his skin was delicate like that of a child; his shining brown hair was waved, his large brown eyes had sympathy in them and also a suggestion of suffering. His voice was rich and deep, surprisingly so far such a slight physique... I recognised him at once as a potential leader; his personality was so dominating, his mind so clear." (23)

In December 1914 Lilla Brockway joined forces with Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Ada Salter, Isabella Ford, Elsie Duval Franklin and Marion Phillips to write an open letter to the women of Germany and Austria. "Some of us wish to send you a word at this sad Christmastide… Though our sons are sent to slay each other, and our hearts are torn by the cruelty of this fate, yet through pain supreme we will be true to our common womanhood. We will let no bitterness enter in this tragedy, made sacred by the life-blood of our best, nor mar with hate the heroism of their sacrifice. Though much has been done on all sides you will, as deeply as ourselves, deplore, shall we not steadily refuse to give credence to those false tales so freely told us, each of the other? Do you not feel with us that the vast slaughter in our opposing armies is a stain on civilisation and Christianity and that still deeper horror is aroused at the thought of those innocent victims, the countless women, children, babes, old and sick, pursued by famine, disease, and death in the devastated areas, both East and West? Peace on earth is gone, but by renewal of our faith that it still reigns at the heart of things. Christmas should strengthen both you and us and all womanhood to strive for its return." (24)

In 1915 the family moved to London, where Fenner Brockway became the No-Conscription Fellowship secretary, renting a room in Bryanston Square, with the baby Frances, born in 1st September, 1915, sleeping in a drawer. (25) Horatio Bottomley, the editor of the John Bull Magazine wrote a full page article demanding Brockway's arrest and execution. (26)

Conscription

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Over 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September, 1914. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until the summer of 1915 when numbers joining up began to slow down. Leo Amery, the MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook pointed out: "Every effort was made to whip up the flagging recruiting campaign. Immense sums were spent on covering all the walls and hoardings of the United Kingdom with posters, melodramatic, jocose or frankly commercial... The continuous urgency from above for better recruiting returns... led to an ever-increasing acceptance of men unfit for military work... Throughout 1915 the nominal totals of the Army were swelled by the maintenance of some 200,000 men absolutely useless for any conceivable military purpose." (27)

The British had suffered high casualties at the Marne (12,733), Ypres (75,000), Gallipoli (205,000), Artois (50,000) and Loos (50,000). The British Army found it difficult to replace these men. In May 1915 135,000 men volunteered, but for August the figure was 95,000, and for September 71,000. Asquith appointed a Cabinet Committee to consider the recruitment problem. Testifying before the Committee, Lloyd George commented: "I would say that every man and woman was bound to render the services that the State they could best render. I do not believe you will go through this war without doing it in the end; in fact, I am perfectly certain that you will have to come to it." (28)

The shortage of recruits became so bad that George V was asked to make an appeal: "At this grave moment in the struggle between my people and a highly-organized enemy, who has transgressed the laws of nations and changed the ordinance that binds civilized Europe together, I appeal to you. I rejoice in my Empire's effort, and I feel pride in the voluntary response from my subjects all over the world who have sacrificed home, fortune, and life itself, in order that another may not inherit the free Empire which their ancestors and mine have built. I ask you to make good these sacrifices. The end is not in sight. More men and yet more are wanted to keep my armies in the field, and through them to secure victory and enduring peace.... I ask you, men of all classes, to come forward voluntarily, and take your share in the fight". (29)

Lord Northcliffe, the press baron, now began to advocate conscription (compulsory enrollment). On 16th August, 1915, the Daily Mail published a "Manifesto" in support of national service. (30) The Conservative Party agreed with Lord Northcliffe about conscription but most members of the Liberal Party and the Labour Party were opposed to the idea on moral grounds. Some military leaders objected because they had a "low opinion of reluctant warriors". (31)

C. P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian, was opposed to conscription, for practical reasons. He explained to Arthur Balfour: "You know that I was honestly willing to accept compulsory military service, provided that the voluntary system had first been tried out, and had failed to supply the men needed and who could still be spared from industry, and were numerically worth troubling about. Those, I think, are not unreasonable conditions, and I thought that in the conversation I had with you last September you agreed with them. I cannot feel that they had been fulfilled, and I do feel very strongly that compulsion is now being forced upon us without proof shown of its necessity, and I resent this the more deeply because it seems to me in the nature of a breach of faith with those who, like myself - there are plenty of them - were prepared to make great sacrifices of feeling and conviction in order to maintain the national unity and secure every condition needed for winning the war." (32)

Margaret Bondfield was opposed to conscription as she thought it would influence the military tactics used in the war: "One of the great scandals of the First World War was the attitude of mind (an old one coming down from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) which regarded human life as the cheapest thing to expend. The whole war was fought on the principle of using up man-power. Tanks and similar mechanical help were received with hesitation and repugnance by commanders, and were inadequately used. But man-power, the lives of men, were used with freedom." (33)

This view was expressed in a pamphlet published by the Independent Labour Party: "The armed forces of the nation have been multiplied at least five-fold since the war began, and recruits are still being enrolled well over 2,000,000 of its breadwinners to the new armies, and Lord Kitchener and Mr. Asquith have both repeatedly assured the public that the response to the appeal for recruits have been highly gratifying and has exceeded all expectations. What the conscriptionists want, however, is not recruits, but a system of conscription that will bring the whole male working-class population under the military control of the ruling classes." (34)

H. H. Asquith, the prime minister, "did not oppose it on principle, though he was certainly not drawn to it temperamentally and had intellectual doubts about its necessity." Lloyd George had originally had doubts about the measure but by 1915 "he was convinced that the voluntary system of recruitment had served its turn and must give way to compulsion". (35) Asquith told Maurice Hankey that he believed that "Lloyd George is out to break the government on conscription if he can." (36)

Brockway wrote an anti-war play, The Devil's Business (1915). In August 1915 the The Labour Leader office in Manchester was raided and Brockway was charged with publishing seditious material. The main objection was a short-story by Isabel Sloan, "which described how a British and German soldier killed each other in battle, but before dying realised that their experiences, their loves and ideals made them one." The government lost its case but soon afterwards bookshops in Manchester and London were raided and material produced by the Independent Labour Party were seized. (37)

Military Service Bill

David Lloyd George threatened to resign if H. H. Asquith, did not introduce conscription. Eventually he gave in and the Military Service Bill was introduced by Asquith on 21st January 1916. John Simon, the Home Secretary, resigned and so did Arthur Henderson, who had represented the Labour Party in the coalition government. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of the Daily News argued that Lloyd George was engineering the conscription crisis in order to substitute himself for Asquith as leader of the country." (38)

In a speech he made in Conwy Lloyd George agreed that Asquith had reluctantly supported conscription, whereas to him, it was vitally important if Britain was going to win the war. "You must organise effort when a nation is in peril. You cannot run a war as you would run a Sunday school treat, where one man voluntarily brings the buns, another supplies the tea, one brings the kettle, one looks after the boiling, another takes round the tea-cups, some contribute in cash, and a good many lounge about and just make the best of what is going on. You cannot run a war like that." He said he was in favour of compulsory enlistment, in the same way as he was "for compulsory taxes or for compulsory education." (39)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, ran a campaign in his Daily Mail against those men refusing to be conscripted. A. J. P. Taylor has argued that Northcliffe and Lloyd George reflected the mood of the British people in 1916: "Popular feeling wanted some dramatic action. The agitation crystallized around the demand for compulsory military service. This was a political gesture, not a response to practical need. The army had more men than it could equip, and voluntary recruitment would more than fill the gap, at any rate until the end of 1916... Instead of unearthing 650,000 slackers, compulsion produced 748,587 new claims to exemption, most of them valid... In the first six months of conscription the average monthly enlistment was not much above 40,000 - less than half the rate under the voluntary system." (40)

In 1916 Fenner Brockway and Clifford Allen were arrested for distributing a leaflet criticizing the introduction of conscription. When they refused to pay their fines, they were sentenced to two months in Pentonville Prison. "We were taken to Pentonville in one of the old horse-drawn Black Marias. Tiny little boxes lined its sides, with larger boxes at the far end. We were all locked in, but we could see and hear each other through grilles. In the passage between the boxes a policeman sat. I served only ten days; the NCF Committee had decided that if Allen were arrested my fine would be paid so that I could direct the organisation." (41)

Soon after being released, Allen was conscripted and prosecuted under the Military Service Act. Allen appeared before the Battersea Tribunal on 14th March, 1916 where he explained why he refused to serve in the armed forces: "I am justified in interpreting my Socialist faith according to my own judgement. There is an increasing number of Socialists who are opposing all war, and I count myself amongst that number. The same might be said of the Christians who believe the churches have abandoned the teaching of Jesus Christ... If every one shared my views there would be no invasion. No civilised country would think of attacking another country unless that country was a source of danger owing to its being armed." Allen also made it clear that he was unwilling to take part at all in the apparatus of war. (42)

Allen won a lot of support from members of the NCF but David Lloyd George, the Secretary of War, who had been one of the leading politicians opposed to the Boer War made a speech where he insisted that conscientious objectors who refused to take any part in the war would be treated harshly: "I do not think they deserve the slightest consideration. With regard to those who object to the shedding of blood it is the traditional policy of this country to respect that view, and we do not propose to depart from it: but in the other case I shall only consider the best means of making the path of that class a very hard one." (43)

On the 17th May, 1916, Fenner Brockway and eight members of the National Committee were arrested and prosecuted under the Defence of the Realm Act. for publishing a leaflet criticising conscription. "We were sentenced to fines of £100 each or two months' imprisonment. The Committee decided to pay the fines in the cases of Edward Grubb and Leyton Richards, but on the appointed day in July the rest of us gave ourselves up at the Mansion House to fulfil the two months' sentence at Pentonville Prison." (44)

In November 1916, Brockway was arrested under the Military Service Act. (45) Brockway had previously been granted exemption from military service on condition that he would do "work of national importance". His friend, Edmund Harvey, the Liberal Party MP for Leeds West and a member of the Society of Friends, defended Brockway by arguing that his work for peace was of "national importance". (46)

While Brockway was in prison, Violet Tillard was appointed General Secretary of the No-Conscription Fellowship, She would visit men in prison. Corder Catchpool later recalled that she was "of inspiration in personal contact, and of strong, quiet leadership in common counsel... Violet Tillard was the first, except one member of my own family, to greet me on my release from prison, and I shall never forget her welcome." (47)

Treated as a traitor, Brockway was held for one night in the Tower of London. He was later transferred to a dungeon at Chester Castle and finally served his sentence in Walton Prison in Liverpool. Brockway continued to write, and after meeting a soldier imprisoned for desertion, wrote an account of the Battle of Passchendaele. The article was discovered and Brockway was sentenced to six days on bread and water. (48) Brockway was released but in July 1917 he was sentenced to two years' hard labour. Brockway, like most other conscientious objectors, was not released from prison until six months after the First World War came to an end. When released in April 1919, he had served a total of twenty-eight months, the last eight in solitary confinement. (49)

Prison Reform

By the time Fenner Brockway was released from prison he had been replaced by Katharine Glasier as editor of the The Labour Leader. He concentrated his efforts on campaigning for Indian independence and became joint secretary of the British Committee of the Indian National Congress. (50)

In 1920 he was appointed as joint secretary with Stephen Hobhouse, of the Prison System Enquiry. Sydney Olivier was chairman and other members included George Bernard Shaw, Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and Margery Fry. The committee took evidence from over 400 witnesses, three hundred of whom were ex-prisoners and one hundred officials such as "warders, chaplains, medical officers, governors, prison magistrates, and officials of the discharged Prisoners Aid Societies." (51)

The report English Prisons Today was published in January 1922. The accounts provided by prisoners caused a sensation. One prisoner serving his first sentence said: "This life reduces one to the level of a wild beast, and every bit of one's better self is literally torn out. If you come to meet me in August, look out for something between a man and a beast." Another man, who was in prison for a third time, wrote: I should like to see anyone make me tender. Why, this life has taken all the feeling out of me. Shall have neither compassion or pity on anyone for the future if they get in my way." (52)

Brockway later pointed out: "The supreme lesson which I learned from my study of criminology and penal methods was that the problem is inseparable from the problem of the social and economic system. The vast majority of those in prison are the victims of economic conditions, and when they leave they have little chance to obtain the security which would encourage them to turn their backs on the petty thefts and similar offences which take them to prison again and again. Most startling of all was the realisation that, intolerable as are the conditions in prison, many actually find them preferable to the hunger and the slum life which are their lot outside." (53)

British Empire, Pacifism and the ILP

In 1922 Fenner Brockway was appointed general secretary of the Independent Labour Party. Brockway also became involved in the campaign for Indian independence and was joint secretary of the British committee of the Indian National Congress. (54) "I had seen the miserable poverty of India under British rule, but I had also met the men who are the leaders of the movement which will make the new India, and I had no doubt that they are equal to the task. Indeed, so far as I had met British political leaders. I came to the conclusion that the Indian leaders were men of greater stature, bigger minds, more creative personality, than the rulers who regarded them unfit to govern. Most of all I rejoiced in the evidence I had of the growth of socialist ideas particularly among the younger people, and of the self-reliant organisation developing among the workers and peasants in opposition not only to political subjection, but to economic subjection." (55)

After the war No-Conscription Fellowship became the No War Movement which became the British section of War Resisters International. Fenner Brockway became chairmen of both organisations. (56) "Those of us who resisted in Britain during the war had little knowledge of other resisters, but we felt confident that our convictions must be held by similar groups in other countries... The beginning of the movement in Germany was of particular interest; it was initiated by two Germans who were interned in this country during the war and who were so impressed by the No Conscription Fellowship that they started a parallel movement as soon as they got back to Berlin and succeeded in forming a quite strong organisation during the reaction against war in the early twenties... Those of us who founded the War Resisters' International insisted from the first that it must be anti-capitalist as well as pacifist... While assistance was given to religious objectors to war, the influence of the organisation was always exerted to emphasise the identity of the struggle against war and the struggle against the economic system which is its cause." (57)

In 1924 Clifford Allen became became chairman of the Independent Labour Party. Some members believed that Allen had not been critical enough of the Labour government led by Ramsay MacDonald. This included Fenner Brockway and James Maxton. (58) Even after MacDonald lost power the conflict continued and on April 1927 Allen "dramatically resigned the chairmanship and, with white face and lips tight shut, walked out." (59)

Maxton replaced Allen as chairman. Henry Noel Brailsford, had been appointed as editor of the Labour Leader in 1922. Brailsford employed several talented writers including George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells and Bertrand Russell. Allen worked closely with Brailsford to produce a new type of political newspaper where the standard of typography and design was as important as its editorial contents. It changed its name to the New Leader. Each issue contained original woodcuts that illustrated articles about politics and culture. By 1923 the newspaper achieved a greatly increased circulation. (60)

However, Brailsford had upset several people in the ILP. Brockway argued: "His (Brailsford) 'highbrow' paper did not reflect the increasingly proletarian temper of the Party; there was also strong criticism of the salaries paid to the Editor and Manager... Socialists aimed at equality; how, then, could we consistently pay a salary of £750 to an official when many members of the Party had only £75 a year?" After coming under attack from people such as Emanuel Shinwell and David Kirkwood, Brailsford resigned as Fenner Brockway became editor. (61)

The General Strike

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (62)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (63)

Henry Hamilton Fyfe was appointed editor. He criticised the trade unionists who tried to stop the newspaper being published. "Trade unionism is a means to an end... to make it an end in itself, to regard its machinery and regulations as if they were scared, is to misapprehended and misuse it." (64)

Fenner Brockway was recruited to take control of the publishing of The British Worker in Manchester. He found the local printing unions willing to help but he was forced to use the Co-operative Printing Society, fifty miles away in Southport and the first Manchester edition of 50,000 copies appeared on Monday and was distributed as far south as Derby, west to Holyhead, east to Hull and north to Carlisle. (65)

Production of the Manchester edition continued up to Saturday, 15th May. "Until the strike was called off", Brockway later reported, "the British Worker was immensely popular. The disappointment with the settlement reacted against the paper, as the organ of the TUC, but there was still a good demand. The attitude of the workers towards the British Worker in the later stages was reflected in the action of the printing chapel, when they were asked whether they would put through a Monday morning edition. They replied that they would not do it for the TUC but would do it as a favour to the firm." (66)

Labour Party MP

Lilla Brockway gave birth to four children Frances (1915), Margaret (1917), Joan (1921) and Olive (1924). According to Lilla the marriage was happy until 1929. "Then she noticed a change in her husband's attitude to her. She became deaf at that time, and it irritated him to have to shout to make her hear. He was then general secretary of the ILP. He confessed that he had been unfaithful to her, but she forgave him. Later he went on a lecture tour to America and he informed her that he was in love with another woman. He asked her to divorce him but she replied that she could not as it would break the hearts of their three children." (67)

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (68)

Fenner Brockway was selected as the Independent Labour Party candidate for East Leyton, a "suburban London constituency, one-third middle-class, two-thirds working-class." According to Brockway he was selected on the understanding that he stood for a programme of "Socialism in Our Time" and "opposition to all armaments and war." (69)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (70)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (71)

A massive campaign in the Tory press against the proposal of increased public spending was very successful. In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. Brockway won the seat from the Conservative candidate, Ernest Alexander. The Liberal Party candidate who finished in third place, Wynne Davies, told Brockway at the count that during the campaign he had converted him to socialism and planned to join the ILP. (72)

A. J. P. Taylor has argued that the idea of increasing public spending would be good for the economy, was difficult to grasp. "It seemed common sense that a reduction in taxes made the taxpayer richer... Again it was accepted doctrine that British exports lagged because costs of production were too high; and high taxation was blamed for this about as much as high wages." (73) Keynes later commented: "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds." (74)

In the House of Commons, Brockway and other ILP members, were critical of the way Ramsay MacDonald and his ministers dealt with the countries economic problems. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden wrote in his notebook on 14th August 1930 that "the trade of the world has come near to collapse and nothing we can do will stop the increase in unemployment." He was growing increasingly concerned about the impact of the increase in public-spending. At a cabinet meeting in January 1931, he estimated that the budget deficit for 1930-31 would be £40 million. Snowden argued that it might be necessary to cut unemployment benefit. Margaret Bondfield looked into this suggestion and claimed that the government could save £6 million a year if they cut benefit rates by 2s. a week and to restrict the benefit rights of married women, seasonal workers and short-time workers. (75)

Unemployment continued to rise and the national fund was now in deficit. Austen Morgan, has argued that when Ramsay MacDonald refused to become master of events, they began to take control of the Labour government: "With the unemployed the principal sufferers of the world recession, he allowed middle-class opinion to target unemployment benefit as a problem... With Snowden at the Treasury, it was only a matter of time before the economic issue was being defined as an unbalanced budget." (76)

In February 1931, on the advice of Philip Snowden, MacDonald asked George May, the Secretary of the Prudential Assurance Company, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. Other members of the committee included Arthur Pugh (trade unionist), Charles Latham (trade unionist), Patrick Ashley Cooper (Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company), Mark Webster Jenkinson (Vickers Armstrong Shipbuilders), William Plender (President of the Institute of Chartered Accountants) and Thomas Royden (Thomas Royden & Sons Shipping Company). (77)

A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out that four of the May Committee were leading capitalists, whereas only two represented the labour movement: "Snowden calculated that a fearsome report from this committee would terrify Labour into accepting economy, and the Conservatives into accepting increased taxation. Meanwhile he produced a stop-gap budget in April, intending to produce a second, more severe budget in the autumn." Snowden made speeches in favour of "national unity" hoping that he would get help from the other political parties to push through harsh measures. (78)

In July, 1931, the George May Committee produced (the two trade unionists refused to sign the document) its report that presented a picture of Great Britain on the verge of financial disaster. It proposed cutting £96,000,000 off the national expenditure. Of this total £66,500,000 was to be saved by cutting unemployment benefits by 20 per cent and imposing a means test on applicants for transitional benefit. Another £13,000,000 was to be saved by cutting teachers' salaries and grants in aid of them, another £3,500,000 by cutting service and police pay, another £8,000,000 by reducing public works expenditure for the maintenance of employment. "Apart from the direct effects of these proposed cuts, they would of course have given the signal for a general campaign to reduce wages; and this was doubtless a part of the Committee's intention." (79)

The five rich men on the committee recommended, not surprisingly, that only £24 million of this deficit should be met by increased taxation. As David W. Howell has pointed out: "A committee majority of actuaries, accountants, and bankers produced a report urging drastic economies; Latham and Pugh wrote a minority report that largely reflected the thinking of the TUC and its research department. Although they accepted the majority's contentious estimate of the budget deficit as £120 million and endorsed some economies, they considered the underlying economic difficulties not to be the result of excessive public expenditure, but of post-war deflation, the return to the gold standard, and the fall in world prices. An equitable solution should include taxation of holders of fixed-interest securities who had benefited from the fall in prices." (80)

Fenner Brockway claimed that in June, 1931, he heard that MacDonald was "entering into secret conversations with representatives of of the Conservative and Liberal Parties to scuttle the Labour Government and to form a National Government." Brockway wrote an article about this in the Labour Leader. The charge was denied by Arthur Henderson, the Foreign Secretary, but not by MacDonald and Snowden. "Later we learned that MacDonald and Snowden had been conferring without the knowledge of their Cabinet colleagues." (81)

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the Cabinet on 20th August. It included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Most members of the Cabinet rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made. Clement Attlee, who was a supporter of Keynes, condemned Snowden for his "misplaced fidelity to laissez-faire economics". (82)

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government." (83)

Arthur Henderson argued that rather do what the bankers wanted, Labour should had over responsibility to the Conservatives and Liberals and leave office as a united party. The following day MacDonald and Snowden had a private meeting with Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare, Herbert Samuel and Donald MacLean to discuss the plans to cut government expenditure. Chamberlain argued against the increase in taxation and called for further cuts in unemployment benefit. MacDonald also had meetings with trade union leaders, including Walter Citrine and Ernest Bevin. They made it clear they would resist any attempts to put "new burdens on the unemployed". Sidney Webb later told his wife Beatrice Webb that the trade union leaders were "pigs" as they "won't agree to any cuts of unemployment insurance benefits or salaries or wages". (84)

At another meeting on 23rd August, 1931, nine members (Arthur Henderson, George Lansbury, John R. Clynes, William Graham, Albert Alexander, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Johnson, William Adamson and Christopher Addison) of the Cabinet stated that they would resign rather than accept the unemployment cuts. A. J. P. Taylor has argued: "The other eleven were presumably ready to go along with MacDonald. Six of these had a middle-class or upper-class background; of the minority only one (Addison)... Clearly the government could not go on. Nine members were too many to lose." (85)

That night MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through." (86)

MacDonald told his son, Malcolm MacDonald, about what happened at the meeting: "The King has implored J.R.M. to form a National Government. Baldwin and Samuel are both willing to serve under him. This Government would last about five weeks, to tide over the crisis. It would be the end, in his own opinion, of J.R.M.'s political career. (Though personally I think he would come back after two or three years, though never again to the Premiership. This is an awful decision for the P.M. to make. To break so with the Labour Party would be painful in the extreme. Yet J.R.M. knows what the country needs and wants in this crisis, and it is a question whether it is not his duty to form a Government representative of all three parties to tide over a few weeks, till the danger of financial crash is past - and damn the consequences to himself after that." (87)

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel, MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself." (88)

On 24th August 1931 MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government. Later that day the King had a meeting with the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal parties. Herbert Samuel later recorded that he told the king that MacDonald should be maintained in office "in view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working class". He added that MacDonald was "the ruling class's ideal candidate for imposing a balanced budget at the expense of the working class." (89)

Later that day MacDonald returned to the palace and had another meeting with the King. MacDonald told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to continue to serve as Prime Minister. George V congratulated all three men "for ensuring that the country would not be left governless." (90)

Ramsay MacDonald was only able to persuade three other members of the Labour Party to serve in the National Government: Philip Snowden (Chancellor of the Exchequer) Jimmy Thomas (Colonial Secretary) and John Sankey (Lord Chancellor). The Conservatives had four places and the Liberals two: Stanley Baldwin (Lord President), Samuel Hoare (Secretary for India), Neville Chamberlain (Minister of Health), Herbert Samuel (Home Secretary), Lord Reading (Foreign Secretary) and Philip Cunliffe-Lister (President of the Board of Trade). (91)

MacDonald's former cabinet colleagues were furious about what he had done. Clement Attlee asked why the workers and the unemployed were to bear the brunt again and not those who sat on profits and grew rich on investments? He complained that MacDonald was a man who had "shed every tag of political convictions he ever had". His so-called National Government was a "shop-soiled pack of cards shuffled and reshuffled". This was "the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country". (92)

The Labour Party's governing national executive, the general council of the TUC and the parliamentary party's consultative committee met and issued a joint manifesto, which declared that the new National Government was "determined to attack the standard of living of the workers in order to meet a situation caused by a policy pursued by private banking interests in the control of which the party has no part." (93)

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with several leading Labour figures, including Fenner Brockway, Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Charles Trevelyan, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hastings Lees-Smith, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, Tom Shaw and Margaret Bondfield losing their seats. Brockway lost his East Leyton by 6,852. (94)

The Government parties polled 14,500,000 votes to Labour's 6,600,000. In the new House of Commons, the Labour Party had only 52 members and the Lloyd George Liberals only 4. George Lansbury, William Adamson, Clement Attlee and Stafford Cripps were the only leading Labour figures to win their seats. The Labour Party polled 30.5% of the vote reflecting the loss of two million votes, a huge withdrawal of support. The only significant concentration of Labour victories occurred in South Wales where eleven seats were retained, many by large majorities. (95)

The Spanish Civil War

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. He also warned the French if they aided the Spanish government and it led to war with Germany, Britain would not help her. The first meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee met in London on 9th September 1936. Eventually 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Portugal, Sweden and Italy signed the Non-Intervention Agreement. Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Non-Intervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship owned by the Nationalists. (96)

The day after Germany signed the Non-Intervention Agreement, Adolf Hitler told his war minister, Field-Marshal Werner von Blomberg, that he wanted to give substantial aid to General Franco. (97) The British government was aware of this but "so long as non-intervention in Spain was imposed without too obvious infringements, so long as Germany remained less committed, politically and militarily, than Italy in the Civil War, some chance of a détente remained." (98)

Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, the Secretary of State for War, admitted that the government was fully aware that its Non-Intervention policy was unsuccessful. "What however it did do was to keep such intervention as there was entirely unofficial, to be denied or at least deprecated by the responsible spokesmen of the nation concerned, so that there was neither need nor occasion for any official action by Governments to support their nationals." (99)

In August 1936, Harry Pollitt, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, arranged for Tom Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the CPGB during the Civil War. Wintringham, along with Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, went out to Spain with the first ambulance unit paid for by the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, a Popular Front organisation supported by the Labour Party. According to the Daily Worker, it left Victoria Station to the cheers of 3,000 supporters who had marched from Hyde Park to see them off led by the Labour mayors from East London boroughs. (100)

While in Barcelona he developed the idea of a volunteer international legion to fight on the side of the Republican Army. He commented: "I believed in the idea of an international legion. Militias can do a lot. But a larger-scale example of military knowledge and discipline, and larger-scale results, are needed too. You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in. You need things big enough to be worth putting in the newspapers." (101)

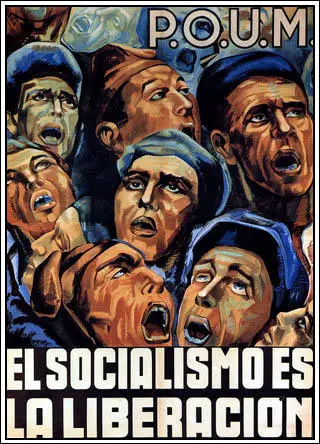

This put Fenner Brockway in a difficult position. He had been a pacifist in the First World War and as a conscientious objector he went to prison for his beliefs. However, he knew that without military support the Republican government would be defeated by fascist forces. (102) Brockway eventually agreed that the Independent Labour Party must send a volunteer force to Spain as part of the International Brigades. "Our contingent left a few hours before the law making the sending of men illegal came into operation, and we had an exciting rush to get them away, acting all the time under the close surveillance of the police." (103)

George Orwell was one of the men sent by Brockway to Spain. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, who was running the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an anti-Stalinist organisation formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. As a result of an ILP fundraising campaign in England, the POUM had received almost £10,000, as well as an ambulance and a planeload of medical supplies. (104)

It has been pointed out by D. J. Taylor, that McNair was "initially wary of the tall ex-public school boy with the drawling upper-class accent". (105) McNair later recalled: "At first his accent repelled my Tyneside prejudices... He handed me his two letters, one from Fenner Brockway, the other from H.N. Brailsford, both personal friends of mine. I realised that my visitor was none other than George Orwell, two of whose books I had read and greatly admired." Orwell told McNair: "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism". Orwell told him that he was also interested in writing about the "situation and endeavour to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France." (106) Orwell also talked about producing a couple of articles for The New Statesman. (107)

McNair went to see Orwell at the Lenin Barracks a few days later: "Gone was the drawling ex-Etonian, in his place was an ardent young man of action in complete control of the situation... George was forcing about fifty young, enthusiastic but undisciplined Catalonians to learn the rudiments of military drill. He made them run and jump, taught them to form threes, showed them how to use the only rifle available, an old Mauser, by taking it to pieces and explaining it." (108)

In January 1937 George Orwell, given the rank of corporal, was sent to join the offensive at Aragón. The following month he was moved to Huesca. Orwell wrote to Victor Gollancz about life in Spain. "Owing partly to an accident I joined the POUM militia instead of the International Brigade which was a pity in one way because it meant that I have never seen the Madrid front; on the other hand it has brought me into contact with Spaniards rather than Englishmen and especially with genuine revolutionaries. I hope I shall get a chance to write the truth about what I have seen." (109)

A report appeared in a British newspaper of Orwell leading soldiers into battle: "A Spanish comrade rose and rushed forward. Charge! shouted Blair (Orwell)... In front of the parapet was Eric Blair's tall figure coolly strolling forward through the storm of fire. He leapt at the parapet, then stumbled. Hell, had they got him? No, he was over, closely followed by Gross of Hammersmith, Frankfort of Hackney and Bob Smillie, with the others right after them. The trench had been hastily evacuated... In a corner of a trench was one dead man; in a dugout was another body." (110)

On 10th May, 1937, Orwell was wounded by a Fascist sniper. He told Cyril Connolly "a bullet through the throat which of course ought to have killed me but has merely given me nervous pains in the right arm and robbed me of most of my voice." He added that while in Spain "I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before." (111)

On 21st September 1938, Juan Negrin announced at the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. This was not a great sacrifice as there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery. (112)

It is estimated that about 5,300 foreign soldiers died while fighting for the Nationalists (4,000 Italians, 300 Germans, 1,000 others). The International Brigades also suffered heavy losses during the war. Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others). Around 10,000 Spanish people were killed in bombing raids. The vast majority of these were victims of the German Condor Legion. (113)

Fenner Brockway later explained. "The war forced on me a dilemma. I was in all my nature opposed to war. I could never see myself killing anyone and had never held a weapon in my hands. But I saw that Hitler and Nazism had been mainly responsible for bringing the war and I could not contemplate their victory. In a sense, the Spanish civil war had settled this dilemma for me; I could no longer justify pacifism when there was a Fascist threat. It had not quite settled it. I was prepared to defend the workers' revolution in Barcelona, but I had no wish to defend Britain's capitalist regime or its imperialist government. I had to compromise. I could not oppose the war unreservedly as I had in 1914, but I would cooperate in civilian activities, and I would work for the ending of the war by Socialist revolution - democratic one hoped." (114)

The Second World War

Brockway was a strong opponent of appeasement. He disagreed with James Maxton who praised Neville Chamberlain for signing an agreement with Adolf Hitler at Munich. Maxton said he did not believe Chamberlain had achieved peace, nor could he as long as capitalism and the Empire bred conflict, but he welcomed the agreement he had signed. Brockway immediately called for a meeting of the Independent Labour Party executive. Brockway argued that Maxton should have denounced the pact as unjust. "Capitalism inevitably led in war to the the slaughter of millions or in peace to the slavery of millions." (115)

Brockway later explained: "My conclusion was that, despite Maxton's powerful analysis of Imperialism and his warning that the war danger would recur if Capitalism persisted, the speech was regrettable from a revolutionary socialist point of view for two reasons: first, for the praise of Chamberlain and, second, for its omission of any denunciation of the terms of the Munich pact. It seemed to me clear that a revolutionary socialist analysis would have denounced the pact mercilessly as illustrating the inability of Capitalism to provide a just alternative to war." (116)

The executive of the ILP agreed with Brockway and some branches called for him to be expelled from the party. At the Scottish ILP Conference in February 1939, Maxton was heckled when he stated that he did not "regret a single word" of his Munich speech. Maxton claimed his proposed expulsion was being sought by men who had been in the ILP for only a few years and who he had defended against expulsions on the grounds they would learn over time. (117)

On 31st August, 1939, Adolf Hitler gave the order to attack Poland. The following day fifty-seven army divisions, heavily supported by tanks and aircraft, crossed the Polish frontier, in a lightning Blitzkrieg attack. A telegram was sent to Hitler warning of the possibility of war unless he withdrew his troops from Poland. That evening Chamberlain told the House of Commons: "Eighteen months ago in this House I prayed that the responsibility might not fall on me to ask this country to accept the awful arbitration of war. I fear I may not be able to avoid that responsibility". (118)

At a meeting of the Cabinet on 2nd September, the Cabinet wanted the prime minister to declare war on Nazi Germany. Chamberlain refused and argued it was still possible to avoid conflict. That night he announced in the House of Commons that he was offering Hitler a conference to discuss the subject of Poland if the "Germans agreed to withdraw their forces (which was not the same as actually withdrawing them), the British government would forget everything that had happened, and diplomacy could start again." (119)

Maxton made a last-minute plea to delay the decision and demanded that if there was to be conscription of labour there should be conscription of wealth. When a MP said that "the Poles are dying in order to save you, you bloody pacifist", John McGovern came to his defence calling the MP a "drunken lout" and reminded him that it was not MPs who would be fighting the war but their constituents. (120)

On 3rd September 1939 Neville Chamberlain went on radio to announce: "Britain is at war with Germany" and went on to say: "This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established." (121)

Maxton remained opposed to the war and refused to support the Emergency Powers Regulations, which gave the Government powers to detain opponents of the state and to censor newspapers and the media. Maxton and other ILP MPs who supported his stand against the war, was criticised by Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party. "Did Maxton hold that peace was right at any price or did he believe in the principle of social justice of which he spoke? Would he give his life for the principle of social justice?" (122)

During the war Brockway felt "cross-pressured between his distaste for militarism and his thorough antipathy to fascism. In wartime by-elections he argued for socialism as a means of ending the war." (123) Brockway later explained: "Hitler triumph had it not been for the epic resistance of her people to the Nazi invasion. Stalingrad was immortal. Churchill's greatness one had to recognise. I did so profoundly as I listened to his broadcast welcoming Russia as an ally despite his hatred of invasions. My thoughts were continually with my associates in France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, typifying many others in their courageous resistance. We were never invaded, never occupied, but our men and women, British and Commonwealth, held fast when all seemed lost. America's intervention was decisive. At rare moments one could escape from tension to be philosophic and recognise that a similar courage, however bad the cause, was shown on the other side. One could also contemplate on the tragedy that all this heroism, all this acceptance of suffering, was directed to war." (124)

Brockway also saw the possibility that the Second World War would result in Capitalism being overthrown and Socialism being introduced. (125) "Towards the end of the war the mood of the people began to change. They had demonstrated national unity against Nazism, but they became increasingly alive to Britain's social inequalities and injustices. The wives of soldiers began to tell of letters expressing a growing resentment among servicemen of the class division between officers and the ranks and of a rising anger against injustice in a society which they had been fighting to defend. Our dream of Socialism after the war was becoming real; we glimpsed the gathering clouds but we did not foresee the storm which would sweep the Churchill Government away when peace came. That was to surprise us all." (126)

Labour MP

On 7th May, 1945, Germany surrendered. Winston Churchill wanted the coalition government to continue until Japan had been defeated, but Clement Attlee, the Deputy Prime Minister and the leader of the Labour Party, refused, and resigned from office. Churchill was forced to form a Conservative government and an election was called for 5th July, with a further three weeks to allow servicemen to vote. (127)

Aneurin Bevan wrote: "At last, the deadly political frustration is ended; at last the unnatural alliance is broken between left and right, between Socialism and Reaction, in other words between forces which on every single issue (bar only the defeat of Nazi Germany) proceed from opposite principles and stand for opposite policies... The sooner the election is held, the sooner we shall be able to get rid of the Tories and begin in earnest with the solution of the tremendous tasks before us." (128)

Labour candidates pointed out that the government had used state control and planning during the Second World War. During the election campaign Labour candidates argued that without such planning Britain would never have won the war. Sarah Churchill told her father in June, 1945: "Socialism as practised in the war did no one any harm, and quite a lot of people good." Arthur Greenwood argued that state planning had proved its value in wartime and would be necessary in peacetime. (129)

When the poll of the 1945 General Election closed the ballot boxes were sealed for three weeks to allow time for servicemen's votes (1.7 million) to be returned for the count on 26th July. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. It came as a surprise that Winston Churchill, who was considered to be the most important figure in winning the war, suffered a landslide defeat. Harold Macmillan commented: "It was not Churchill who lost the 1945 election; it was the ghost of Neville Chamberlain." (130)

Fenner Brockway left Lilla Brockway and began a relationship with Edith Violet King, a Clerical Assistant. In 1939 they were living at 10 Neville's Court, Chancery Lane, London. Whereas Lilla was living in Sevenoaks Road, Sevenoaks, Kent, carrying out "unpaid domestic duties". (131) In July 1945 Lilla Brockway obtained a divorce "on the grounds of the misconduct of her husband". (132)

After Labour's election success, he decided that the Independent Labour Party offered no distinctive way forward and rejoined the Labour Party. During this period Brockway was chairman of the British Centre for Colonial Freedom and in 1945 he helped establish the Congress of Peoples against Imperialism. He was also selected as the Labour candidate for Eton and Slough. (133).

Fenner Brockway won the seat in the 1950 General Election. In the House of Commons he joined the Keep Left Group that included Ian Mikardo, Richard Crossman, Michael Foot, Konni Zilliacus, John Platts-Mills, Lester Hutchinson, Leslie Solley, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, George Wigg, John Freeman, Richard Acland, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin. They urged Clement Attlee to develop left-wing policies and were opponents of the cold war policies of the United States and urged a closer relationship with Europe in order to create a "Third Force" in politics. (134)

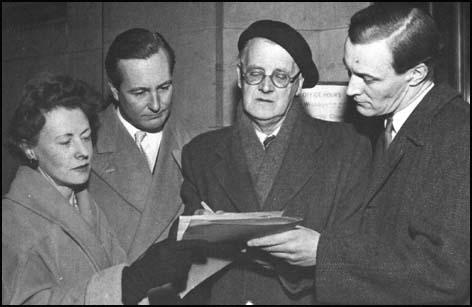

attacking Herbert Morrison, Clement Attlee and Hugh Gaitskell (July, 1951)

Fenner Brockway interest in Indian independence had been long-standing, and from 1950 he began to visit Africa regularly. "Some called him the member for Africa and he knew several of the first generation post-independence African leaders." From 1954 he was chairman of the Movement for Colonial Freedom. His anti-colonialism was reflected in a thorough opposition to racism in Britain. In nine successive sessions he introduced bills into the Commons aimed at outlawing discrimination. He was also one of the founders of War on Want and the Anti-Apartheid Movement. (135)

Tony Benn organizing a petition against Apartheid in South Africa

On 2nd November, 1957, the New Statesman published an article by J. B. Priestley entitled Russia, the Atom and the West. In the article Priestley attacked the decision by Aneurin Bevan to abandon his policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. The article resulted in a large number of people writing letters to the journal supporting Priestley's views. (136)

Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman, organised a meeting of people inspired by Priestley and as result they formed the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Early members of this group included Fenner Brockway, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Wilfred Wellock, Ernest Bader, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, E. P. Thompson, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, Stuart Hall, Ralph Miliband, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot.

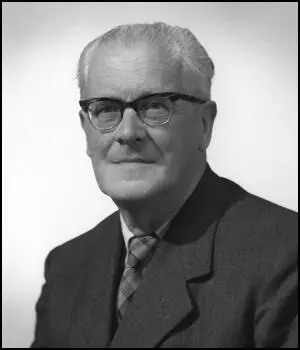

House of Lords

Fenner Brockway lost his seat at the 1964 General Election. "I was defeated in 1964 at Eton and Slough by eleven votes, partly on the colour issue, more so by poor organization." Harold Wilson asked him to go to the House of Lords. "I said I didn't believe in the place but was prepared to use it as a platform. That I tried for many years to do, putting more questions, initiating more debates and introducing more Bills than any other back-bencher. (137)

Brockway wrote over twenty books on politics. This including four volumes of autobiography: Inside the Left (1942), Outside the Right (1963), Towards Tomorrow (1977) and 98 Not Out (1986). Fenner continued to campaign for world peace and was president of the British Council for Peace in Vietnam and chairman of the World Disarmament Campaign (1979-88). According to one biographer, David Howell, "his radicalism remained vibrant in his new environment. (138)

Brockway was distressed by the election of Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister: "I suppose Mrs Thatcher must be described as a Creator of Our Time. I regard it as a bad time, strengthening competitiveness in society instead of co-operation... I hate fundamentally nearly all that Mrs Thatcher has done as Prime Minister, but I acknowledge her dedication to her convictions. She believes in capitalism and has applied her beliefs. I wish many Labour spokesmen believed in Socialism as completely." (139)

Fenner Brockway died on 28th April 1988, six months before his 100th birthday.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1907 Fenner Brockway interviewed James Keir Hardie for the Daily News.

He told me how he had gone down the mine as a boy, wished to be a journalist, taught himself shorthand with a pin on a slate, organised the first miners' union at this pit of virtual slavery; how how he was nominated as Liberal Parliamentary candidate but turned it down because he was a working man. He told me of his formation of the Scottish Labour Party, how he became a Socialist after meeting European miners' leaders, how he initiated the Independent Labour Party in 1893 and was elected to Parliament for West Ham. He described how he worked to win the Trade Union Movement to political independence and his gratification when Labour was returned as a group in 1906, and then, his voice warming, explained what Socialism meant to him, his confidence in its triumph, and his belief that by international action the workers of Europe would prevent war. I cannot convey the depth of his ringing Scottish accent as he declared his faith. I went to him as a Young Liberal and left him a Young Socialist

(2) Fenner Brockway was an active supporter of votes from women. In his autobiography Towards Tomorrow, he commented on the tactics that were used.

It was ironical that Lloyd George, when he gave the vote to women in 1919 (though even then not on the same terms as men) declared that they deserved it for their war service and this was widely accepted as the explanation of their success in 1919. I regard this as a myth. I believed they would have won the vote earlier and on better terms if there had been no war. If the General Election due in 1915 had taken place there is little doubt that the supporters of women's suffrage would have been in a majority in the House of Commons.

(3) Fenner Brockway was sent to prison in 1916 for refusing to be conscripted. He was one of the most popular speakers at public meetings organised by pacifists during the First World War.

Every individual gives loyalty to something which counts more than anything else in life. In most men and women this supreme allegiance is inspired by national patriotism; if their Government becomes involved in a war it is a matter of course they will support it. The socialist conscientious objector has a group loyalty which is as powerful to him as the loyalty of the patriot for his nation. His group is composed of workers of all lands, the dispossessed, the victims of the present economic system, whether in peace or war.

(4) In 1916 Fenner Brockway was imprisoned for refusing to be recruited to the armed forces.

After a brief stay at Scotland Yard I was taken to the Tower of London and locked in a large dungeon where there were twenty or so prisoners, mostly sitting or lying on a sloping wooden platform, which I learned was a communal bed, running the length of the longer wall. Six of the prisoners, still in civilian clothes, were objectors.

I was to be taken to Chester Castle and my wife travelled to Chester with me. The Cheshire Regiment did not have a good reputation for its treatment of objectors. The previous week the newspaper had carried reports of how George Beardsworth and Charles Dukes, both subsequently prominent trade union leaders, had been forcibly taken to the drilling ground and kicked, punched, knocked down and thrown over railings until they lay exhausted, bruised and bleeding. I was a little apprehensive.

(5) The Daily Herald (24 September 1923)

Fenner Brockway takes the helm at a difficult time for the Independent Labour Party. Enthusiasm is less easy to rouse than in the old days; the very success of the great Labour Party itself has narrowed the possible field of the recruitment of the ILP, and many of the new recruits seem to possess less "stickability" than the old. The socialist vision is sometimes a trifle obscured in the terms of everyday bread and butter Labour politics. But Fenner knows these things, and is not the man to be daunted by them.

He is still young, but his years have been packed full of rich and varied experiences. He started his professional career as a Congregational magazine located at Memorial Hall; from there he went to the "Christian Commonwealth," in Salisbury Square; and then to Manchester, first as sub-editor of Labour Leader, under J. F. Mills, and afterwards as editor.

He was in control of the Labour League in August, 1914, when the war broke upon the world, and I have always believed that by his actions at the very outset, in swinging the paper quite definitely on the side of peace, he did more than any other one man to decide the war-time policy of the ILP.

He was the founder of the No-Conscription Fellowship (suggested by his wife, Lilla Brockway); he went to prison himself.

When a year or two ago, there was a stirring among the somewhat dry bones of the ILP, Fenner Brockway played his part in the salutary process, in the capacity of the Press and publicity agent. Last year he was appointed as national organising secretary of the party, and his appointment to the general secretaryship has quickly followed.

Fenner is a member of the National Union of Journalists and I record here with pleasure one incident which is to his lasting credit. When the clerks at the ILP head office were on strike in the early part of 1920, he was then working at the head office as London correspondent of the Labour Leader. He straightaway refused to work in an office which was being picketed by clerks on strike, and forthwith removed his fountain pen and papers in the more congenial atmosphere of York Buildings.

(6) Fenner Brockway was the editor of The British Worker during the 1926 General Strike.

The General Strike failed because the TUC never believed in it; the Government forced it on them by the impulsive Downing Street action. It was said the strike was beginning to break, but in most industrial centres the problem was not to keep the workers out but to keep the exempted workers in. The betrayal of the miners was the worst consequence. Under the leadership of Yorkshire Herbert Smith, the chairman, dour and of few words, and of Welsh Arthur Cook, the secretary, extrovert and of many words, they decided to carry on alone. I came to admire Cook greatly. In contrast with many union leaders he never left the rank and file. During the nine months' struggle he refused a salary, taking the lock-out pay and nothing else. He was loved by his men, and never spared himself, travelling night after night from coalfield to coalfield. Admittedly he failed and the miners were driven back to work at cruel wage reductions. Admittedly a shrewder negotiator might have gained a better result earlier.

(7) Martin Ceadel, Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980)

Spain proved an even more damaging blow to socialist "pacifism" than Abyssinia. Striving to keep the W.R.I. pacifist, Runham Brown predicted stoically to Ponsonby on 27 September 1936: In these days of crisis may will depart from us but we shall be proved right and ultimately we shall win. Our job is to keep our Movement steady. We now have to face a more difficult position raised by the Spanish War. Some like Fenner Brockway will leave us, but we shall go on.

Spain did, indeed, complete Brockway's gradual process of realization, which had begun with the Russian revolution and was later considerably furthered by the political and economic crisis of 1931, that the absolute socialist pacifism which had led him to found the N.C.F. in 1914 was, in reality, an extreme socialist pacificism.

(8) Fenner Brockway, Inside the Left (1942)

I had long put on one side the purist pacifist view that one should have nothing to do with a social revolution if any violence were involved... Nevertheless, the conviction remained in my mind that any revolution would fail to establish freedom and fraternity in proportion to its use of violence, that the use of violence inevitably brought in its train domination, repression, cruelty.

(9) Fenner Brockway, Inside the Left (1942)