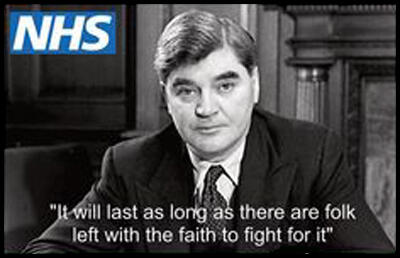

Aneurin Bevan

Aneurin Bevan, was born at 32 Charles Street, Tredegar, on 15th November 1897. It was one of a long row of four-roomed miners' cottages. He was the sixth of ten children born to Phoebe and David Bevan, of whom only eight survived infancy and only six to adulthood. (1)

Both Aneurin's parents were Nonconformists. His father was a Baptist and his mother a Methodist. David Bevan was a miner, as was his father, was an active trade-unionist. In his youth he had been a supporter of the Liberal Party in his youth but was converted to socialism by the writings of Robert Blatchford in the Clarion newspaper. (2)

David Bevan was a gentle, thoughtful man, who loved reading, wrote poetry, sang in the chapel and was treasurer of the local branch of the National Union of Mineworkers. As with most miners, he suffered from the choking black dust disease, pneumoconiosis, that was to eventually kill him. (3) He worked underground for the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company as did two-thirds of the adult males of the town. (4)

Phoebe Bevan was not very interested in politics. She was the "dominating personality in the home, a strict disciplinarian and a formidably efficient housekeeper". According to one biographer: "Though his love of books was his father's... the determination, energy and practicality that drove Aneurin to try putting dreams and theories into effect was clearly inherited from his mother. The two sides of his personality could hardly be more obviously attributable." (5)

Bevan disliked school and was often in conflict with William Orchard, headmaster of Sirhowly School. On one occasion, Orchard asked one of his friends why he had not been to school the day before and when he replied that it was his brother's turn to wear the shoes, he mocked him. Bevan reacted by throwing an inkwell at his headmaster. It is believed that his experiences at school caused him to develop an appalling stutter. His friend, Michael Foot, has suggested that this speech impediament "was bread at school either by Orchard's bullying or his teaching methods or a combination of the two". (6)

Aneurin Bevan: Coalminer

At the age of eleven he worked after school at a butcher's boy, earning 2s 6d a week for long hours which involved staying open until midnight on Saturdays and one o'clock on Sundays. Then, on his thirteenth birthday, in November 1910, he went to work with his father in the Ty-Tryst colliery for 7 shillings a week. (7)

Although a strong boy he found the work exhausting: "Down below are the sudden perils - runaway trains hurtling down the lines; frightened ponies kicking and mauling in the dark, explosions, fire, drowning. And if he escapes? There is a tiredness which leads to stupor, which forms a dull persistent background to your consciousness. This is the tiredness of the miner, particularly of the boy of fourteen or fifteen who falls asleep over his meals and wakes up hours later to find that his evening has gone and there is nothing before him but bed and another day's wrestling with inert matter." (8)

Bevan developed a love of reading. He joined the Tredegar Workmen's Institute Library where he read the works of H. G. Wells, Jack London, James Connolly, Daniel de Leon and Eugene V. Debs. He was also a keen attender at Plebs League classes given fortnightly at Blackwood, by Sydney Jones. A fellow student, Harold Finch, later claimed that Bevan was "the star of the class". (9) John Campbell has pointed out that "under Jones's influence he went beyond the cautious agnosticism of most of those who were rejecting their chapel upbringing, to embrace the daring certainty of outright atheism." (10)

Bevan also joined the Tredegar branch of the South Wales Miners' Federation. He soon became a union activist and by the time he was nineteen he was chairman of his Miners' Lodge. Bevan became a well-known local orator and was seen by his employers, the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company, as a revolutionary. The manager of the colliery found an excuse to get him sacked. However, with the support of the Miners' Federation, the case was judged as one of victimization and the company was forced to re-employ him.

Trade Unionism

Bevan was also deeply influenced by the teachings of Noah Ablett, the leader of South Wales syndicalism. (11) Ablett was an evangelist of aggressive Marxism who produced a pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step (1912). Ablett called for a new type of unionism: "A united industrial organisation, which, recognising the war of interest between workers and employers, is constructed on fighting lines, allowing for a rapid and simultaneous stoppage of wheels throughout the mining industry." (12)

Bevan also began attending the Tredegar branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Like most members of the ILP, Bevan was an opponent of Britain's involvement in the First World War. In 1917 he was called up under the government's Conscription Act. He refused to join the British Army and claimed he would choose his own enemy and his own battlefield and would not let the Government do it for him. He was eventually rejected on health grounds as he suffered from nystagmus. (13)

Over the next two years Bevan was active in anti-war campaigns across Wales. In 1919 he won a scholarship to the Central Labour College in London, where promising young trade unionists could learn about Labour Party history and Marxist economics. Bevan spent two years studying economics, politics and history at the college. It was during this period that Bevan read the Communist Manifesto and was converted to the ideas of Karl Marx and Frederich Engels. (14) Bevan did not enjoy his time at college as he "was very much a loner, preferring to study on his own rather than attend classes he found dull". (15)

While at college Bevan was given elocution lessons by Clara Bunn. Reciting long passages by William Morris, Bevan gradually began to overcome the stammer that he had since he was a child. According to his friend, Michael Foot, the main way he cured his stutter by making speeches in public. (16) As another biographer pointed out, by speaking in public he "mastered the demon by meeting it head on." (17)

When Bevan returned home in 1921 the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company refused to employ him. For the next three years he was without work. During this time Bevan worked as an unpaid adviser to people living in Tredegar. Bevan considered emigrating to Australia but in 1924 he found work at Bedwellty Colliery. After ten months the owners decided to close the colliery down and Bevan had to endure another year of unemployment. In February 1925, Bevan's father died of pneumoconiosis in his arms. He claimed that just before he died he was asking for the Daily Herald and news of John Wheatley, socialist minister responsible for housing in the first Labour government of 1923–4. (18)

In 1926 Bevan was employed as a union official. His wages of £5 a week was paid by the members of the local Miners' Lodge. On 15th April 1926, the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company, like all colliery companies, posted at the pit-head lock-out notices. When the General Strike started on 3rd May 1926, Bevan soon emerged as one of the leaders of the South Wales miners. He gave his full support to A. J. Cook, general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers. (19)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street to announce to the British Government that the General Strike was over. At the same meeting the TUC attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers. This the Government refused to do. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (20)

After the TUC leaders called off the strike, the miners remained locked-out for six months. Bevan was largely responsible for the distribution of strike pay in Tredegar and the formation of the Council of Action, an organisation that helped to raise money and provided food for the miners. When the Western Mail published an attack on A. J. Cook, he organized a huge procession in the town where copies of the newspapers were burnt. (21)

House of Commons

In 1928 Bevan was elected to the Monmouthshire County Council. The following year Bevan was selected by the Labour Party of Ebbw Vale to be their candidate in the forthcoming parliamentary election. In the 1929 General Election, Bevan easily defeated his Liberal and Conservative opponents. His first speech in the House of Commons was an attack on Winston Churchill, his main enemy during the 1926 General Strike. Aneurin Bevan also became a fierce critic of Margaret Bondfield, the Minister of Labour, for her unwillingness to increase unemployment benefits.

Dai Smith has argued: "It was Bevan's very ability to combine social self-confidence with an abiding contempt for existing social structures which made him so dangerous an opponent in the cut and thrust of parliamentary debate: he oozed triumphalism, and he was, whenever the circumstance threatened to translate it into reality, hated more deeply for this by his political opponents than any other figure in mainstream politics in the twentieth century." (22)

Bevan became friendly with Jennie Lee, the MP for North Lanarkshire. She later recalled: "We had been defeated on the industrial front in 1919, 1921 and 1926. We were both now pinning our hopes on political action. We were eager to test to the full the possibility of bringing about basic socialist changes by peaceful, constitutional means. If we could avoid direct industrial confrontation, leading to a civil war in which our side almost certainly would be the weaker... Some other countries had no choice, Russia for instance. But maybe our people could be spared the agonies of civil war." (23)

Bevan was one of the most outspoken opponents of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government. He was furious when The Daily Mail "printed horror stories of people getting a few shillings from the dole to which they were not entitled, the impressionable MacDonald began talking of married women turning up to collect dole money wearing fur coats." (24)

Bevan led the campaign against the introduction of the Means Test. In the House of Commons Bevan argued that the "purpose of the Means Test is not to discover a handful of people receiving public money when they have means to supply themselves. The purpose is to compel a large number of working-class people to keep other working-class people, to balance the Budget by taking £8 to £10 millions from the unemployed." (25)

Aneurin Bevan wrote to John Strachey where he explained he welcomed the split in the Labour Party. "In the guise and cloak of patriotism the government was making war upon the poorest members of the community. As fas as we are concerned, there is one thing about which we are pleased in the present crisis, and that is that the changeover of this party from there to here has clearly exposed the class issue. We shall carry it through to a final conclusion, be the circumstances what they may." (26)

In 1931 G.D.H. Cole created the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (SSIP). This was later renamed the Socialist League. Other members included Aneurin Bevan, William Mellor, Charles Trevelyan, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Gilbert Mitchison, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. It is claimed that the organisation had about 3,000 members but enjoyed an influence out of proportion to its size.

Margaret Cole, one of the founders of the organization, admitted that they got some of the members from the Guild Socialism movement: "Douglas and I recruited personally its first list drawing upon comrades from all stages of our political lives." The main objective of the organisation was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies. (27) John T. Murphy, left the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) to become secretary of the Socialist League. He explained that he saw "the organization of revolutionary socialists who are an integral part of the Labour movement for the purpose of winning it completely for revolutionary socialism." (28)

Bevan agreed with other Socialist League members that the Labour Party was too attached to "gradualist" ideas. He believed that that this approach would always be defeated by the power of capitalism. R. H. Tawney pointed out that "onions can be beaten leaf by leaf but you cannot skin a live tigar paw by paw". Bevan argued that any future Labour government had to immediately nationalize the joint stock banks as well as the Bank of England.

In April 1933, Aneurin Bevan and a group of left-wing MPs and academics, signed a letter urging the Labour Party to form a United Front against fascism, with other socialist political groups. However, the idea was rejected at that year's party conference. The same thing happened the following year with seventy-five amendments put forward by the Socialist League was thrown out by large majorities. (29)

During this period Bevan argued for socialist solutions to the economic problems that faced the country. Bevan hated the market system and the price mechanism. He believed they undermined the legitimate prerogative of democratic processes. Bevan argued that Parliament should manage the economy for the benefit of the working people and, if it did not own the major industries, how could it manage the economy. (30)

Bevan never supported Welsh nationalism. "Though notably Welsh in English eyes, Bevan was a distinctly cosmopolitan figure who lacked sympathy with Welsh identity and separatist thinking and scorned local nationalism as a divisive force that would merely isolate the people from the mainstream of British life; he believed that the economic problems afflicting Wales were exactly the same as those in the rest of Britain." (31)

Jennie Lee had been involved in an intense affair with the married Frank Wise. When he died suddenly on 5th November, 1933, Lee moved in with Bevan. "Both railed against social conventions and both, but especially Jennie, insisted on maintaining freedom, sexual and professional, outside any partnership. None the less, and with this agreed, they married in October 1934." (32)

The couple became active in the Committee for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism. To Bevan and Lee, the rise of fascism was an accurate fulfillment of the prophecies made by Karl Marx. Opposition to fascism was vitally important if a socialist society was to be created in the future. During this period he upset leaders of the Labour Party by appearing on the same platform as the CPGB. He also attacked the "cowardice" of the party. Emanuel Shinwell argued: "If Bevan or anyone else believes that the Party is insipid or lacking in courage... then in my judgement they ought to join the Party or organization which they believe has got the attributes that the Labour Party ought to have." (33)

Campaign Against Fascism

In 1936 the Conservative government in Britain feared the spread of communism from the Soviet Union to the rest of Europe. Stanley Baldwin, the British prime minister, shared this concern and was fairly sympathetic to the military uprising in Spain against the left-wing Popular Front government. Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, initially agreed to send aircraft and artillery to help the Republican Army in Spain. However, after coming under pressure from Baldwin and Anthony Eden in Britain, and more right-wing members of his own cabinet, he changed his mind.

In the House of Commons on 29th October 1936, Clement Attlee, Philip Noel-Baker and Arthur Greenwood argued against the government policy of Non-Intervention. As Noel-Baker pointed out: "We protest with all our power against the sham, the hypocritical sham, that it now appears to be." G.D.H. Cole and Jack Murphy, the General Secretary of the Socialist League also called for help to be given to the Popular Front government. Bevan claimed that the government's "professed neutrality was only a cover for an instinctive class sympathy Franco which several backbench Tories from Churchill downwards openly admitted." (34)

Aneurin Bevan also called on help for the Spanish government: "Should Spain become Fascist, as assuredly it will if the rebels succeed, then Britain's undisputed power in the Meditterranean is gone. we shall be too weak to offer any formidable resistance to the Fascist Governments of Germany, Italy and Spain who will form an alliance. We must form an alliance with France, Spain, Russia and Turkey so as to become so powerful that we shall never have any fear of the Fascists breaking the peace." (35) Despite the passionate speech from Bevan support for non-intervention was carried by 1,836,000 votes to 519,000. (36)

Bevan also joined with other left-wing Labour Party MPs that campaigned for the formation of a Popular Front with other left-wing groups in Europe to prevent the spread of fascism. At the 1936 Labour Party Conference, several party members, including George Strauss, Ellen Wilkinson, Stafford Cripps and Charles Trevelyan, argued that military help should be given to the Spanish Popular Front government, fighting for survival against General Francisco Franco and his right-wing Nationalist Army. Bevan told delegates: "Is it not obvious to everyone that if the arms continue to pour into the rebels in Spain, our Spanish comrades will be slaughtered by hundreds of thousands... and democracy in Europe will soon be in ruins." (37)

Along with George Strauss, Emanuel Shinwell, Sydney Silverman and Ellen Wilkinson Bevan toured Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Shinwell later wrote: "The reason for the defeat of the Spanish Government was not in the hearts and minds of the Spanish people. They had a few brief weeks of democracy with a glimpse of all that it might mean for the country they loved. The disaster came because the Great Powers of the West preferred to see in Spain a dictatorial Government of the right rather than a legally elected body chosen by the people." (38)

On 31st October, 1936 the Socialist League called an anti-fascist conference in Whitechapel and discussed the best ways of dealing with Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. Over the next few months meetings were held. The Socialist League was represented by Aneurin Bevan, Stafford Cripps and William Mellor, the Communist Party of Great Britain by Harry Pollitt and Palme Dutt and the Independent Labour Party by James Maxton and Fenner Brockway. (39)

After the success of the Left Book Club during the summer of 1936, Bevan and other members of the left-wing of the Labour Party began to believe there was a market for a socialist weekly newspaper. In January 1937 Stafford Cripps and George Strauss decided to launch a radical weekly, The Tribune, to "advocate a vigorous socialism and demand active resistance to Fascism at home and abroad." William Mellor was appointed editor and others such as Aneurin Bevan, Ellen Wilkinson, Barbara Betts, Konni Zilliacus, Harold Laski, Michael Foot and Noel Brailsford agreed to write for the paper. Winifred Batho reviewed films and books for the journal. Mellor wrote in the first issue: "It is capitalism that has caused the world depression. It is capitalism that has created the vast army of the unemployed. It is capitalism that has created the distressed areas... It is capitalism that divides our people into the two nations of rich and poor. Either we must defeat capitalism or we shall be destroyed by it." (40)

Bevan wrote a weekly column, Inside Westminster. "Bevan is not normally thought of as much of a writer; but these weekly articles reveal a surprisingly good journalist. Though strictly political, their variety expresses the richness of his mind, always able to focus a general argument on a telling detail or extrapolate an historical theory from a trivial episode. As well as major polemics there are a host of throwaway epigrams, satirical squibs, some very accomplished sketch-writing and - undoubtedly most irritating to the leaders and loyalists of the PLP - a continuous commentary, usually critical, sometimes merely patronising, on Labour's parliamentary performance." (41)

During this period Bevan often found himself in conflict with his party leader, Clement Attlee. However, he had a lot of respect for Attlee: "He has a clear and subtle mind and it has always been a pity that a certain lack of horse power has prevented him from 'getting across' as he should... His position in the party is much stronger than I am afraid he thinks it is. To make him realise this would be of itself a considerable contribution to the success of the Party." (42)

Bevan used his column to attack the government led by Neville Chamberlain. He argued at the 1937 National Conference that the Labour Party should not give any support to Chamberlain's foreign policy, including his desire to spend large sums of money on the military. Bevan believed that the present government could not be trusted to use this new military power against its own people: "We are not going to put a sword in the hands of our enemies that may be used to cut off our own heads." However, Bevan was easily defeated by 2,167,000 to 228,000 when the vote was taken. (43)

Winston Churchill accused Bevan of giving the impression to Adolf Hitler that Britain was divided. Bevan rejected Churchill's argument that "the Opposition must refrain from opposing because if he does so Hitler will hear of it and be encouraged thereby. The fear of Hitler is to be used to frighten the workers of Britain into silence. In short Hitler is to rule Britain by proxy. If we accept the contention that the common enemy is Hitler and not the British capitalist class, then certainly Churchill is right. But it means abandment of the class struggle and the subservience of the British workers to their own employers." (44)

Bevan argued that Chamberlain's policy of appeasement was "proto-fascist" as it had supported General Francisco Franco in Spain and was "bending over backwards to secure a treaty with fascist Italy". Meanwhile it rejected the possibility of co-operation with the Soviet Union which geography dictated was the only way of stopping Adolf Hitler, "had it been serious about doing so". (45)

Aneurin Bevan wrote in The Tribune: "The people of this country must be made to realise that the danger of war arises from this government's refusual to mobilise the peace forces of the world. It is prevented by its own class bias from entering into building alliances with countries like Soviet Russia and its permits the fabric of collective peace to be destroyed by the gangster methods of Hitler and Mussolini." (46)

Bevan was convinced that Conservative opponents were not reliable allies. He admired Churchill's resolution against Hitler, but reminded his followers that he was an "unrepentant imperialist and supporter of Franco". He also criticised Anthony Eden, who had resigned from Chamberlain's government over the issue of appeasement: "Beneath the sophistication of his appearance and manner he has all the unplumbable stupidities and unawareness of his class and type." (47) He also felt he should have resigned in such a way as would have "ruined Chamberlain". (48)

Stafford Cripps, a senior figure in the Labour Party, called for the creation of a Popular Front against fascism. The campaign opened officially with a large meeting at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 24th January, 1938. Three days later the Executive of the Labour Party decided to disaffiliated the Socialist League. They also began considering expelling members of the League. G.D.H. Cole and George Lansbury responded by urging the party not to start a "heresy hunt".

In May 1938, Aneurin Bevan gave a speech at Pontypool where he gave support to the idea and said the country could "drift to disaster under the National Government" or "the establishment of a Popular Front... under the leadership of the Labour Party." He admitted that he admired Churchill's resolution against Hitler, but reminded his audience that he was an "unrepentant imperialist and supporter of Franco". (49)

Bevan spoke on the same platform with members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. In his autobiography, Very Little Luggage, his friend, Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, explained what happened: "The result was that Cripps, Bevan and myself (midget though I was beside such men) received a letter of anathema from the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party. We were told that we would be expelled from the Labour Party if we continued to appear on platforms that included Communists.... So I found myself sitting in an office in Chancery Lane with Cripps and Bevan while Cripps held up the letter to re-read the National Executive's terms for our rehabilitation. Cripps treated it as though it were a document replete with indecent details in a carnal knowledge case. Bevan said something about preferring to be out than in. The way things were going, so he said, it was no time to be mealy-mouthed. So they refused to assure the National Executive that they would in future keep more right-wing company." (50)

In January 1939, Stafford Cripps, prepared a long memorandum for the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party, outlining the case for a Popular Front against fascism. He also circulated it to the constituencies and as a result was expelled from the party. Bevan was furious and argued: "If Sir Stafford Cripps is expelled for wanting to unite the forces of freedom and democracy, they can go on expelling others... His crime is my crime." (51)

In an article in The Tribune: "Cripps was expelled because he claimed the right to tell the Party what he had already told the Executive... This is tantamount to a complete suppression of any opinion in the Party which does not agree with that held by the Executive... If every organised effort to change Party policy is to be described as an organised attack on the Party itself, then the rigidity imposed by Party discipline will soon change into rigor mortis." (52)

On 31st March 1939, Aneurin Bevan, George Strauss and Charles Trevelyan were expelled from the Labour Party. Bevan continued to attack the NEC. So did other party members. David Low published a cartoon showing Colonel Blimp saying: "The Labour Party is quite right to expel all but sound Conservatives." However, they were readmitted in November 1939 after agreeing "to refrain from conducting or taking part in campaigns in opposition to the declared policy of the Party."(53)

The Second World War

At the beginning of the Second World War Aneurin Bevan became the foremost parliamentary critic of Neville Chamberlain and his government. "If this war is to be won by a collapse in Germany, it can only be done by first breaking down the moral authority of the National Government... If we have no confidence in the Chamberlain Government why should the German worker?" (54)

Clement Attlee rejected Bevan's view that Labour should try to bring down Chamberlain. Attlee thought the revolt against Chamberlain should come from the Conservatives and that Labour should only watch and wait. "Bevan grew impatient: the war was already being used to bring in Tory measures (the Government had taken power to limit wage rises, but not to limit profits) and there was no sign of a Conservative rebellion." (55)

On the outbreak of the war public opinion polls showed that Chamberlain's popularity was 55 per cent. By December, 1939, this had increased to 68 per cent. However, members of the House of Commons saw him as an uninspiring war leader. On 7th May, 1940, Leo Amery, the Conservative MP, argued in the House of Commons: "Just as our peace-time system is unsuitable for war conditions, so does it tend to breed peace-time statesmen who are not too well fitted for the conduct of war. Facility in debate, ability to state a case, caution in advancing an unpopular view, compromise and procrastination are the natural qualities - I might almost say, virtues - of a political leader in time of peace. They are fatal qualities in war. Vision, daring, swiftness and consistency of decision are the very essence of victory." Looking at Chamberlain he then went onto quote what Oliver Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go." (56)

The following day, the Labour Party demanded a debate on the Norwegian campaign and this turned into a vote of censure. At the end of the debate 30 Conservatives voted against Chamberlain and a further 60 abstained. Chamberlain now decided to resign and on 10th May, 1940, George VI appointed Winston Churchill as prime minister. Later that day the German Army began its Western Offensive and invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Two days later German forces entered France.

Churchill formed a coalition government and placed leaders of the Labour Party such as Clement Attlee (Deputy Prime Minister), Ernest Bevin (Minister of Labour), Herbert Morrison (Home Secretary), Stafford Cripps (Minister of Aircraft Production), Arthur Greenwood (Minister without Portfolio) and Hugh Dalton (Minister of Economic Warfare) in key positions. He also brought in another long-time opponent of Chamberlain, Anthony Eden, as his secretary of state for war.

Bevan condemned Churchill's decision to keep leading appeasers such as Neville Chamberlain (Lord President of the Council), Lord Halifax (Foreign Secretary), Kingsley Wood (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and John Simon (Lord High Chancellor) in senior positions in the government. He argued that Bevin and Morrison were the right men for their posts "yet Labour was only being allowed to put petrol in the car: the Tories still held the steering wheel." (57)

of Commons, Punch Magazine (1944)

Once Churchill was in power, Bevan used his influence as editor of Tribune and the leader of the left-wing MPs in the House of Commons, to shape government policies. Bevan opposed the heavy censorship imposed on radio and newspapers and wartime Regulation 18B that gave the Home Secretary the powers to lock up citizens without trial. When the government banned the Daily Worker he argued that the newspaper was "detestable but harmless" and the real reason for its suppression was that it was "intended to serve as an instrument of intimidation against the Press as a whole". (58)

John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) has argued: "There was a lot of fine talk about democracy during the war and a good deal of national self-congratulation that the forms of parliamentary government were maintained; but after the formation of the Coalition in May 1940 there was no regular opposition in the House of Commons except that offered by a few maverick malcontents of whom Bevan was increasingly the most prominent and by far the most consistent." (59)

Bevan believed that the Second World War would give Britain the opportunity to create a new society. He often quoted Karl Marx who had said in 1885: "The redeeming feature of war is that it puts a nation to the test. As exposure to the atmosphere reduces all mummies to instant dissolution, so war passes supreme judgment upon social systems that have outlived their vitality." At the beginning of the 1945 General Election campaign Bevan told his audience: "We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders. We enter this campaign at this general election, not merely to get rid of the Tory majority. We want the complete political extinction of the Tory Party."

1945 General Election

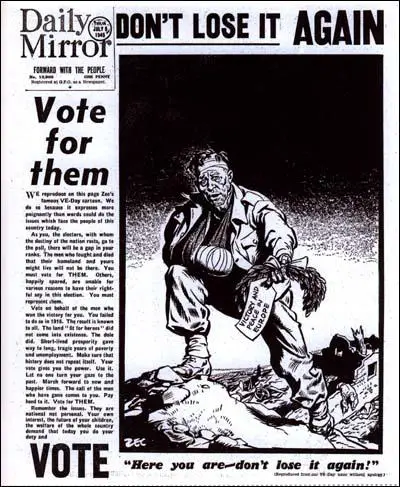

In its manifesto, Let us Face the Future, it made clear that "the Labour Party is a Socialist Party, and proud of it. Its ultimate purpose at home is the establishment of the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain - free, democratic, efficient, progressive, public-spirited, its material resources organised in the service of the British people.... Housing will be one of the greatest and one of the earliest tests of a Government's real determination to put the nation first. Labour's pledge is firm and direct - it will proceed with a housing programme with the maximum practical speed until every family in this island has a good standard of accommodation. That may well mean centralising and pooling of building materials and components by the State, together with price control. If that is necessary to get the houses as it was necessary to get the guns and planes, Labour is ready." (60)

The manifesto argued for the state takeover of certain branches of the economy - the Bank of England, coal mines, electricity and gas, railways, and iron and steel. This reflected some of the measures passed by the Labour Conference in December 1944. However, some left-wing commentators pointed out that the "nationalisation measures were justified on grounds of economic efficiency, not as a means of shifting the balance between labour and capital." (61)

The document made it clear that if elected it would pass legislation to protect the working-class: "The Labour Party stands for freedom - for freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of the Press. The Labour Party will see to it that we keep and enlarge these freedoms, and that we enjoy again the personal civil liberties we have, of our own free will, sacrificed to win the war. The freedom of the Trade Unions, denied by the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act, 1927, must also be restored. But there are certain so-called freedoms that Labour will not tolerate: freedom to exploit other people; freedom to pay poor wages and to push up prices for selfish profit; freedom to deprive the people of the means of living full, happy, healthy lives".

The Labour Party also stated its commitment to a National Health Service: "By good food and good homes, much avoidable ill-health can be prevented. In addition the best health services should be available free for all. Money must no longer be the passport to the best treatment. In the new National Health Service there should be health centres where the people may get the best that modern science can offer, more and better hospitals, and proper conditions for our doctors and nurses. More research is required into the causes of disease and the ways to prevent and cure it. Labour will work specially for the care of Britain's mothers and their children - children's allowances and school medical and feeding services, better maternity and child welfare services. A healthy family life must be fully ensured and parenthood must not be penalised if the population of Britain is to be prevented from dwindling." (62)

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

On 4th June, 1945, Winston Churchill made a radio broadcast where he attacked Clement Attlee and the Labour Party: "I must tell you that a socialist policy is abhorrent to British ideas on freedom. There is to be one State, to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State, once in power, will prescribe for everyone: where they are to work, what they are to work at, where they may go and what they may say, what views they are to hold, where their wives are to queue up for the State ration, and what education their children are to receive. A socialist state could not afford to suffer opposition - no socialist system can be established without a political police. They (the Labour government) would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo." (63)

Ian Mikardo believed that the Churchill broadcast helped his election campaign: "In his first election broadcast on the radio he warned the country that if they elected a Labour government they would find themselves under the jackboots of a socialist gestapo. The British people just wouldn't take that. They looked at Clem Attlee, the timid, correct, undemonstrative, unaggressive ex-public-schoolboy, ex-major, and couldn't see an Adolf Hitler in him." (64)

Attlee's response the following day caused Churchill serious damage: "The Prime Minister made much play last night with the rights of the individual and the dangers of people being ordered about by officials. I entirely agree that people should have the greatest freedom compatible with the freedom of others. There was a time when employers were free to work little children for sixteen hours a day. I remember when employers were free to employ sweated women workers on finishing trousers at a penny halfpenny a pair. There was a time when people were free to neglect sanitation so that thousands died of preventable diseases. For years every attempt to remedy these crying evils was blocked by the same plea of freedom for the individual. It was in fact freedom for the rich and slavery for the poor. Make no mistake, it has only been through the power of the State, given to it by Parliament, that the general public has been protected against the greed of ruthless profit-makers and property owners. The Conservative Party remains as always a class Party. In twenty-three years in the House of Commons, I cannot recall more than half a dozen from the ranks of the wage earners. It represents today, as in the past, the forces of property and privilege. The Labour Party is, in fact, the one Party which most nearly reflects in its representation and composition all the main streams which flow into the great river of our national life." (65)

Labour candidates pointed out that the government had used state control and planning during the Second World War. During the election campaign Labour candidates argued that without such planning Britain would never have won the war. Sarah Churchill told her father in June, 1945: "Socialism as practised in the war did no one any harm, and quite a lot of people good." Arthur Greenwood argued that state planning had proved its value in wartime and would be necessary in peacetime. (66)

When the poll closed the ballot boxes were sealed for three weeks to allow time for servicemen's votes (1.7 million) to be returned for the count on 26th July. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. It came as a surprise that Winston Churchill, who was considered to be the most important figure in winning the war, suffered a landslide defeat. Harold Macmillan commented: "It was not Churchill who lost the 1945 election; it was the ghost of Neville Chamberlain." (67)

Henry (Chips) Channon recorded in his diary what happened on the first day of the new Parliament: "I went to Westminster to see the new Parliament assemble, and never have I seen such a dreary lot of people. I took my place on the Opposition side, the Chamber was packed and uncomfortable, and there was an atmosphere of tenseness and even bitterness. Winston staged his entry well, and was given the most rousing cheer of his career, and the Conservatives sang 'For He's a Jolly Good Fellow'. Perhaps this was an error in taste, though the Socialists went one further, and burst into the 'Red Flag' singing it lustily; I thought that Herbert Morrison and one or two others looked uncomfortable." (68)

The Labour Government

Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison and Ernest Bevin, the senior figures in the government, were all on the right of the party. The new intake of MPs included far fewer from working-class backgrounds. According to one historian, "with apparent satisfaction the new prime minister noted that he had appointed no fewer than twenty-eight public school boys, including seven Etonians, five Haileyburians and four Winchester men, to the government." (69)

The most significant figure on the left was Aneurin Bevan. He argued for a comprehensive programme of nationalisation as without state control, there could be no true socialism because there could be no planning: "In practice it is impossible for the modern State to maintain an independent control over the decisions of big business. When the State extends its control over big business, big business moves in to control the State. The political decisions of the State become so important a part of the business transactions of the combines that is the law of their survival that those decisions should suit the needs of profit-making. The State ceases to be the umpire. It becomes the prize." (70)

Attlee was also not enthusiastic about the nationalisation programme proposed by Ian Mikardo at the 1944 Labour Conference and in the Labour manifesto, Let us Face the Future. However, it now had the support of the vast majority of its membership and he agreed to put it into operation. As Hugh Dalton pointed out: "We weren't really beginning our Socialist programme until we had gone past all the utility junk - such as transport and electricity - which were publicly owned in every capitalist country in the world. Practical Socialism... really began with Coal and Iron and Steel, and there was a strong political argument for breaking the power of a most dangerous body of capitalists." (71)

Herbert Morrison, the deputy prime minister, had always been strongly opposed to the nationalisation of Iron and Steel. He began negotiations with Sir Andrew Duncan, chairman of the British Iron and Steel Federation, in order to avoid it being taken into public ownership. (72) Aneurin Bevan responded by arguing that the Labour government should keep its manifesto's commitment: "Suggestions will be made that some parts of the industry are efficient and satisfactory and so should be left alone, but I am opposed to the Government taking over the cripples and leaving the good things to private ownership." (73)

Herbert Morrison and the left of the party (1947)

A few weeks later, Bevan argued: "Democracy means that if you hurt people they have the right to squeal. But when you hear the squeals you must carefully find out who is squealing. If the right people are squealing then we are doing the job properly... So far we have been all right and here is the whole delusion of coalition of national co-operation. You cannot focus the full national will on the main evils of society, because in a coalition there are people who benefit from the very evils themselves." (74)

National Health Service

After the 1945 General Election, Clement Attlee, the new Labour Prime Minister, appointed Bevan as Minister of Health. According to John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) it was "a remarkable appointment for Attlee to bring Bevan straight into the Cabinet as Minister of Health - by far the boldest stroke in a generally cautious exercise in rewarding the long-serving party faithful." At forty-seven Bevan was by some years the youngest member of a Cabinet whose average age was over sixty." (75)

In 1946 Parliament introduced the revolutionary National Insurance Act. It instituted a comprehensive state health service, effective from 5th July 1948. The Act provided for compulsory contributions for unemployment, sickness, maternity and widows' benefits and old age pensions from employers and employees, with the government funding the balance. It promised an all-embracing social insurance scheme from the "cradle to the grave", a system which would give people benefits as of right, and without a means test. (76)

The government announced plans for a National Health Service that would be, "free to all who want to use it." The legislation established "a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement in the physical and mental health of the people of England and Wales and the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of illness and for that purpose to provide or secure the effect of provision of services." (77)

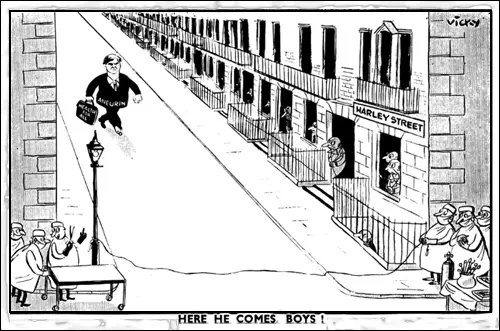

Some members of the medical profession opposed the government's plans. Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA) mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. The main complaint of the BMA was that the NHS would "turn doctors from free-thinking professionals into salaried servants of central government". (78)

Opposition to National Health Service

The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion." (79)

Winston Churchill led the attack on Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." (80) However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced". (81)

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor." (82)

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany. (83)

National Health Service Act

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions." (84)

The Manchester Guardian commented on the passing of the National Health Service Act: "These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution." (85)

In October 1950, Clement Attlee promoted Hugh Gaitskell to chancellor of the exchequer. Aneurin Bevan considered Gaitskell as hostile to the National Health Service and sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement." (86)

One of Gaitskell's first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon." (87)

Resignation of Aneurin Bevan

The following day, Aneurin Bevan resigned from the government. In a speech he made in the House of Commons he explained why he had made this decision: "The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million... If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct. Is that right?... The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop?"

Bevan went on to argue that this measure was undermining the Welfare State: " Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right honourable friends cannot escape.... After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?" (88)

attacking Herbert Morrison, Clement Attlee and Hugh Gaitskell (July, 1951)

Bevan served for a short period as Minister of Labour in 1951 but resigned on 21st April with Harold Wilson and John Freeman when Hugh Gaitskell, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that he intended to introduce measures that would force people to pay half the cost of dentures and spectacles and a one shilling prescription charge. For the next five years Bevan was the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Bevan's Tribune group criticised high defence expenditure (especially over nuclear weapons) and opposed the reformist policies of Clement Attlee.

Bevan's radicalism was less marked after 1956 when he agreed to serve the new leader, Hugh Gaitskell, as shadow foreign secretary. In October, 1957 he decided to make a speech against unilateral nuclear disarmament at the party conference. His wife, Jennie Lee, disagreed strongly with his decision: "I did not argue with him that evening, he had to be left in peace to work things out for himself, but he was in no doubt that I would have preferred him to take the easy way. I dreaded the violence of the Conference atmosphere which I knew would be generated by the dedicated advocates of immediate unilateral nuclear disarmament, but, like Nye, I did not foresee the bitterness of the personal attacks made by some delegates who ought to have known him well enough not to have doubted his motives. Disagreement was one thing: character assassination another. Were these his friends? Were these his comrades he had fought for over so many years? Could they really believe that he was a small-time career politician prepared to sacrifice his principles in order to become second-in-command to the right-wing leader of the Party?

Bevan later recalled: "I knew this morning that I was going to make a speech that would offend and even hurt many of my friends. I know that you are deeply convinced that the action you suggest is the most effective way of influencing international affairs. I am deeply convinced that you are wrong. It is therefore not a question of who is in favour of the hydrogen bomb, but a question of what is the most effective way of getting the damn thing destroyed. It is the most difficult of all problems facing mankind. But if you carry this resolution and follow out all its implications and do not run away from it you will send a Foreign Secretary, whoever he may be, naked into the conference chamber."

Aneurin Bevan became deputy leader of the Labour Party in 1959, but he was already a very ill man and died of cancer on 6th July, 1960.

Primary Sources

(1) Aneurin Bevan, The Daily Express (1932)

In other trades there are a thousand diversions to break the monotony of work - the passing traffic, the morning newspaper, above all, the sky, the sunshine, the wind and the rain. The miner has none of these. Every day for eight hours he dies, gives up a slice of his life, literally drops out of life and buries himself. The alarum or the "knocker-up" calls him from his bed at half past four. He makes his way to the pithead. The streets are full of shadows with white faces and black-rimmed sunken eyes.

Down below are the sudden perils - runaway trams hurtling down the lines, frightened ponies kicking and mauling in the dark, explosions, fire, drowning. And if he escapes? There is a tiredness as the reward of exertion, a physical blessing which makes sleep a matter of relaxed limbs and muscles. This is the tiredness of the miner, particularly of the boy of fourteen or fifteen who falls asleep over his meals and wakes up hours later to find that his evening has gone and there is nothing before him but bed and another day's wrestling with inert matter.

(2) In 1921 Aneurin Bevan wrote an article in Plebs Magazine on the Communist Manifesto.

The Communist Manifesto stands in a class by itself in Socialist literature. No indictment of the social order ever written can rival it. The largeness of its conception, its profound philosophy and its sure grasp of history, its aphorisms and its satire, all these make it a classic of literature, while the note of passionate revolt which pulses through it, no less than its critical appraisement of the forces of revolt, make it for all rebels an inspiration and a weapon.

(3) Aneurin Bevan wrote about his first impressions of the House of Commons in his book In Place of Fear (1952)

The House of Commons is like a church. The vaulted roofs and stained glass windows, the rows of statues of great statesmen of the past, the echoing halls, the soft-footed attendants and the whispered conversations, contrast depressingly with the crowded meetings and the clang and clash of hot opinions he has just left behind in the election campaign. Here he is, a tribune of the people, coming to make his voice heard in the seats of power. Instead, it seems he is expected to worship; and the most conservative of all religions - ancestor worship.

(4) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

Sir Stafford Cripps and Aneuryn Bevan led the radical Labour grouping that was unequivocal in its opposition to appeasement. The left's earlier pacifist tinge had withered under the heat of the Spanish Civil War. The bellicose, menacing, voices of Hitler and Mussolini needed to be met with a simple refusal to be intimidated. It was obvious that the Axis was playing for our surrender without a fight, which is exactly what Munich promised. The Holborn Constituency Labour Party, along with scores of others, was anti-appeasement and for a policy of standing up to the Dictators. This was also the position of the European Popular Fronts, and it involved accepting common cause with everyone who was of like mind, including, at that particular moment, the Communist Parties. The result was that Cripps, Bevan and myself (midget though I was beside such men) received a letter of anathema from the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party. We were told that we would be expelled from the Labour Party if we continued to appear on platforms that included Communists. The reason I was being grouped with the great for this call-to-order was that I had been doing a lot of speaking in London and had been billed with Cripps (who turned out to be a distant cousin) on a number of occasions. Though I was perfectly happy in Holborn and though I was not looking for a parliamentary career, there had been talk of finding me another constituency with better electoral prospects. So I found myself sitting in an office in Chancery Lane with Cripps and Bevan while Cripps held up the letter to re-read the National Executive's terms for our rehabilitation. Cripps treated it as though it were a document replete with indecent details in a carnal knowledge case. Bevan said something about preferring to be out than in. The way things were going, so he said, it was no time to be mealy-mouthed. So they refused to assure the National Executive that they would in future keep more right-wing company. Bevan turned to me and said that expelling me would do no one any good because it would not make the splash that his expulsion and that of Cripps would cause. "You can do more good by thanking them for their letter and simply saying that you have noted its contents. They will leave you alone for a bit and, before they get round to going after you again, we shall all be in this together. " Bevan was sure that Chamberlain had made war a certainty by giving Hitler the idea that he could walk over Britain.

This post-Munich meeting is especially interesting as Cripps, the cooler mind of the two, also thought that war was probable but that France, Britain and the Soviet Union could still unite in a last chance to call Hitler's bluff. They felt their own expulsion from the Labour Party would help to galvanise public opinion in the face of the real risk of appeasement sliding on towards a tolerant acceptance of fascism. "And that," said Cripps to me," is where you can help in leading the younger side of the Labour Movement." "Stay in but don't knuckle under," said Bevan. There was nothing starry-eyed about this. We now know that Chamberlain's Government was secretly informed by General Beck, Chief of the German General Staff, that Great Britain only had to take a decisive stand at the time of the Nazi attack on Czechoslovakia and then the German professional Army would have toppled Hitler. This was between the 18th and the 24th of August 1938, and we had another chance in June of 1939. Churchill himself wrote, when looking back at those years, "There never was a war more easy to stop.“ Had we done so Stalinism would never have lasted a further forty years.

(5) Jennie Lee, Tomorrow is a New Day (1948)

Aneurin and I were at the cottage that Sunday in September when war was declared. We tuned into the one o'clock news for official confirmation that the fight had really begun. We had discussed all this so often and so much. Now at last it had come. Our enemy Hitler had become the national enemy. All those who hated fascism would have their chance to fight back. No more one-sided massing of all the wealth, influence and arms of international reaction against the workers of first one country then another. I thought of Spain. I had a guilty feeling about Spain. I said something to Aneurin that must have indicated the drift of my thoughts. He had been pacing up and down our long, low, white-washed cottage room, for once too excited for words. He stopped walking up and down to rummage in a corner among a disorderly pile of gramophone records. He found what he was looking for. He found records we had not dared to play for more than a year: the marching songs of the Spanish Republican armies.

(6) The Western Mail (December, 1941)

Every mannerism that he (Aneurin Bevan) cultivates, every speech he delivers, even the expression he wears in the most familiar photographs, bear witness to a profound consciousness of his own superiority. Socialists may believe in the equality of other folk, but Mr. Bevan always conveys the impression of living at a greater intellectual attitude than the rest of the miners' leaders.

(7) In March 1942 the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, threatened to ban the Daily Mirror after it published a cartoon by Philip Zec that criticised war profiteering. In the House of Commons Bevan defended Zec's cartoon.

I do not like the Daily Mirror and I have never liked it. I do not see it very often. I do not like that form of journalism. I do not like the strip-tease artists. If the Daily Mirror depended upon my purchasing it, it would never be sold. But the Daily Mirror has not been warned because people do not like that kind of journalism. It is not because the Home Secretary is aesthetically repelled by it that he warns it. I have heard a number of honourable members say that it is a hateful paper, a tabloid paper, a hysterical paper, a sensational paper, and that they do not like it. I am sure the Home Secretary does not take that view. He likes the paper. He is taking its money (waves cuttings of articles written by Morrison for the Daily Mirror).

He (Morrison) is the wrong man to be Home Secretary. He has for many years the witch-finder of the Labour Party. He has been the smeller-out of evil spirits in the Labour Party for years. He built up his reputation by selecting people in the Labour Party for expulsion and suppression. He is not a man to be entrusted with these powers because, however suave his utterance, his spirit is really intolerant. I say with all seriousness and earnestness that I am deeply ashamed that a member of the Labour Party should be an instrument of this sort of thing.

How can we call on the people of this country and speak about liberty if the Government are doing all they can to undermine it? The Government are seeking to suppress their critics. The only way for the Government to meet their critics is to redress the wrongs from which the people are suffering and to put their policy right.

(8) Aneurin Bevan, Tribune (23rd April, 1942)

The Government has tried everything to solve the problem of the mining industry. Semi-starvation, imprisonment, extortions, threats, the supplications of the miners' leaders, and what is almost the omnipotence of Churchill's oratory - all have failed. There is one thing they have not tried. They haven't tried getting rid of the coalowners. For the one truth the Government have not learned. You can get coal without coalowners, but you cannot get coal without miners. Let us not lose heart. The miners will teach it them one day.

(9) Aneurin Bevan, Tribune (January, 1944)

As Socialists we are bound to in duty to support Soviet Russia when it acts as a progressive Socialist power. But it is equally our Socialist obligation to raise our voice against any attempts of the strong as trampling over the rights of the weak. As Socialists we fight the reactionary ambitions and claims of the Poles; but we must defend Poland's right to self-determination and independence just as we defend the rights of any other nation oppressed or threatened by oppression.

(10) Barbara Castle, Fighting All The Way (1993)

As news of these feats of endurance seeped through to Britain the suspicion began to grow that some people in the British establishment would not be too unhappy to see Russia expend herself unaided in tying Hitler down, and the clamour for the opening of a second front to relieve Russia's agony grew in intensity. Aneurin Bevan was its most vociferous advocate both in the columns of Tribune and in Parliament. He was rapidly emerging as the most challenging figure on the left of politics, a thorn in the flesh of the Labour leadership and the favourite bogeyman of the right-wing press. He was politically and physically the product of the South Wales mining community from which he sprang; of stocky build and defiant temperament he was blessed with the gift of Welsh oratory that could encapsulate the experience of less articulate people in a vivid phrase. He once summed up his socialism with the words, "You can get coal without coal owners, but you cannot get coal without miners." It was the sort of phrase to set alight the political imagination of the most moderate. He had climbed from the pits to Parliament by fighting the coal owners and it had left him with bitter memories of the struggles he and his fellow miners had had to wage.

This bitterness was to be the source of both his strength and his weaknesses. He came into Parliament with a heavy sense of responsibility to the people among whom he had grown up and to his own class, and it gave him an outsize courage which few other politicians possessed. I did not know him well personally at that time but I was stirred by the accounts of his one-man battles in the House with Churchill the Goliath. The audacity of it was breathtaking, for Churchill was our war leader at the peak of his authority and a hero to everyone else.

Aneurin also deeply distrusted Churchill politically. He had warmly supported his replacement of Chamberlain, but was shocked when he proceeded to appease the appeasers by keeping so many of them in his War Cabinet. Even Chamberlain was retained as Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House, while the arch-Municheer, Lord Halifax, remained Foreign Secretary. Nor could Nye forgive Churchill's sudden assumption of the leadership of the Conservative Party in the middle of the war.

(11) Aneurin Bevan, speech at a Labour Party meeting (July, 1945)

There is no absence of knowledge, there is no lack of wisdom, as to what to do in Great Britain. What is lacking is that the power lies in the wrong hands and the will to do it is not there. We want to tell our friends on the other side that the men in the Services are not going to allow a repetition of what happened between the wars. We are not going to allow our financial resources to be sent all over the world, and idleness and starvation to exist in Great Britain. And we warn them we are entering this fight with this in our hearts. We were brought up between the two wars in the distressed areas of this country, and we have such biting and bitter memories we will never be erased until the Tories are destroyed on every political platform in the country. We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders. We enter this campaign at this general election, not merely to get rid of the Tory majority. We want the complete political extinction of the Tory Party.

(12) In her book My Life With Nye, Jennie Lee describes how one woman responded to the introduction of the National Health Service.

There was a strict rule in Nye's Ministry that any unsolicited gifts sent to him should be promptly returned. On one occasion, and only one, an exception was made. Nye brought home a letter containing a white silk handkerchief with crochet round the edge. The hanky was for me. The letter was from an elderly Lancashire lady, unmarried, who had worked in the cotton mills from the age of twelve. She was overwhelmed with gratitude for the dentures and reading glasses she had received free of charge. The last sentence in her letter read, "Dear God, reform thy world beginning with me," but the words that hurt most were, "Now I can go into any company." The life-long struggle against poverty which these words revealed is what made all the striving worthwhile.

(13) Fred Copeman, Reason in Revolt (1948)

It is no accident that Nye, born in the mining valleys of Wales, should be the most popular leader in the Labour Movement today. The new Health Bill could have no better champion. Fearless in debate, brilliantly intelligent in the political field, I have always been able to call Nye my friend, and am honoured to do so. We have had our battles (what Chairman of Housing worth his salt hasn't had them with the Minister of Health ?) but I always found him big enough to fight clean. I shall always remember a small incident at the reception given by the General Council of the T.U.C. at Norwich. I was introduced to Aneurin Bevan and he immediately asked me to go and get him a drink, in what I thought a rather high and mighty way. Feeling my position as Brigade Commander, I told him, " Go and get your own bloody drink." He laughed and replied, " All right, lad, and I'll get one for you too." I've looked back on this small incident as a rather bad show of conceit on my part and darned good nature on his. Nye keeps his enthusiasm burning. Above all he refuses to be drawn from the level of those who nurtured him - the workers. No fur coats here, nor top hats; I notice these things and so do millions of other workers. Ideologies are built on big ideas and simple actions, they start and finish with individuals.

(14) Aneurin Bevan, speech at a Labour Party meeting in Manchester (4th July, 1945)

No amount of cajolery, and no attempts at ethical or social seduction, can eradicate from my heart a deep burning hatred for the Tory Party that inflicted those bitter experiences on me. So far as I am concerned they are lower than vermin. They condemned millions of first-class people to semi-starvation. Now the Tories are pouring out money in propaganda of all sorts and are hoping by this organised sustained mass suggestion to eradicate from our minds all memory of what we went through. But, I warn you young men and women, do not listen to what they are saying now. Do not listen to the seductions of Lord Woolton. He is a very good salesman. If you are selling shoddy stuff you have to be a good salesman. But I warn you they have not changed, or if they have they are slightly worse than they were.

Human beings are complex creatures, and most generalisations about them give little light... I don't think a Tory, considered as a person, is any worse or better than anyone else. The private morals of many of our leading Tories are beyond reproach, whereas their public morals are execrable. In their personal circle they would hesitate to tell lies, yet in public, deception is accepted as part of their technique of government.

(15) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986)

Hugh Gaitskell had many fine qualities, including unswerving loyalty to his close band of friends and to the principles of economics as he interpreted them, together with great personal charm. But once he came to a decision, a remarkably speedy process associated with great certainty, the Medes and the Persians had nothing on him. Whether the argument took place in the Cabinet, or later in the Shadow Cabinet or the National Executive, any colleague taking a different line from his was regarded not only as an apostate, but as a troublemaker or simply a person lacking in brains.

Hugh Gaitskell and Nye Bevan were as temperamentally and politically opposed to one another as it was possible to be within a single political party. I had relations of fairly long standing with both of them. I had first come close to Nye during my housing stint at the Ministry of Works, although it had taken time for the relationship to develop. Nye was suspicious of university-trained MPs, particularly those from Oxford and above all economists, but I had broken down that barrier and we had great confidence in each other. I had early developed an admiration for Hugh Gaitskell's qualities and in many way we were intellectual partners. He was more doctrinaire and I was more of a pragmatist.

One other fact soon became clear about Hugh. He was certainly ambitious, and had close links with the right-wing trade unions. It was not long before that ambition took the form of a determination to outmanoeuvre, indeed humiliate, Aneurin Bevan. Hugh, for his part, despised what he regarded as emotional oratory, and if he could defeat Nye in open conflict, he would be in a strong position to oust Morrison as the heir apparent to Clement Attlee. At the same time he would ensure that post-war socialism would take a less dogmatic form, totally anti-communist but unemotional.

(16) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

At a private meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party in the early autumn of 1948 the subject of Bevan's 'vermin' reference came up. It will be all too well remembered that at an otherwise unimportant gathering at Manchester in July Bevan had recalled the burning hatred he had felt during his youth for the Tories. "So far as I am concerned," he had finished, "they are lower than vermin."

This remark came not long after he had said, at a pre-conference rally at Blackpool in May, that the British press was the most prostituted in the world. Not unnaturally the journalists were both voluntarily, and probably by editorial order, on the watch for the slightest chance to lambast their accuser and the result was headlines for the 'vermin' statement.

At the meeting I said that the best thing for the cause of socialism would have been for some prominent Tory to have called us vermin. Bevan was extremely annoyed at this and worked himself into a high pitch of indignation at the fuss being made about what he called an unimportant comment. Its importance or unimportance was perhaps better left to the opinion of Laski, an expert in making such estimates, who put the Tory gain from the 'vermin' slight at two million votes. I do not regard this as an exaggeration.

In face of the continued refusal of his colleagues to dismiss the words as unimportant Bevan fell back on the suggestion that he had been misreported. I am afraid that on occasion he is an expert in saying things which the shorthand writers seem to get wrong. I believe that he genuinely believes that he said something else and his more excitable and ill-advised outbursts must to some extent be forgiven because of his temperament. At a political meeting he lives as part of his audience. He is partly its master and partly its creature. When he is speaking to an audience which is almost entirely on his side there is applause for something he says which finds favour. This goes to his head and he is tempted against his better judgment to say something more to the audience's liking in order to transform the applause into an ovation.

(17) Aneurin Bevan, letter to Richard Stafford Cripps (July, 1950)

I have made it clear to you, the Prime Minister, and Gaitskell that I consider the imposition of charges on any part of the Health Service raises issues of such seriousness and fundamental importance that I could never agree to it. If it were decided by the Government to impose them, my resignation would automatically follow. Despite this, spokesmen of the Treasury and you have not hesitated to press this so-called solution upon the Government. But surely it must be apparent to you that it can hardly create friendly relations if, in spite of the knowledge of how seriously I regard this question, you continue to press it. I am not such a hypocrite that I can pretend to have amiable discourses with people who are entirely indifferent to my most strongly held opinions.

(18) John Freeman letter to Aneurin Bevan (April, 1950)