Noah Ablett

Noah Ablett, the tenth of eleven children of John Ablett, a miner, and his wife, Jane Williams Ablett, was born near Porth on 4th October 1883. After a brief elementary education, at the age of twelve, he joined his father and elder brothers at the Standard Colliery. He also developed a reputation as a local lay preacher. (1)

Ablett continued his education by reading the works of Karl Marx and other socialist writers. He joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and in 1907 he began a correspondence course scholarship at Ruskin College. It had been established by Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman, in February, 1899. It was a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people. (2)

Ruskin Hall was also called a "College of the People" and the "Workman’s University". It was to be a residential institution providing study opportunities for a whole year or for shorter periods as appropriate. The residential element of the College’s work in its early years was open to men only. Harold Pollins pointed out: "It was to be part of a nationwide movement in order to cater for the large number who wanted to study but would not be able to take time off work. Provision for them, women as well as men, would be in two parts: correspondence courses, and extension classes in their own localities taught by the Ruskin Hall Faculty and by other lecturers." (3)

Dennis Hird was appointed as the the college's first principal. Hird was a member of the Social Democratic Federation and the former rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor and a leading member of the Christian Socialist movement. Hastings Lees-Smith was appointed as vice-principal and taught economics and as he was a supporter of the free-market he upset the socialist students. After being appointed chairman of the executive committee, he attempted to remove sociology and evolution from the curriculum. However, Hird had enough support to block the move. (4)

According to Hywel Francis, "he quickly made his mark on educational thinking at Ruskin, and organized classes in Marxian economics and history as an alternative to the traditional liberal curriculum". (5) Bernard Jennings agrees that Ablett had a considerable influence over the students at Ruskin: "Tensions began to build as increasing numbers of students became ardent socialists. They enjoyed Hird's lectures on sociology, a major element of which was the study of evolution, on which he had written a popular book. They disliked Lees Smith's lectures on economics, although acknowledging his ability as a teacher, because his adherence to current free-market theories was just as dogmatic as that of the left-wing students to Marxism." (6)

Ablett set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In January 1909, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. Over the next few weeks branches were established in five towns in the coalfield. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits. (7) Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique". (8)

In 1907 Hastings Lees-Smith, who was later to become a Liberal Party MP, was appointed professor of economics at University College, but he did not relax his grip on Ruskin. He became chairman of Ruskin College's executive committee and was chief adviser on studies. He appointed, Charles Buxton, aged 23 as vice-principal, and Henry Sanderson Furniss to lecture on economics, who both shared his view "of the relationship between class improvement and education". (9)

Hastings Lees-Smith tried to marginalise Dennis Hird by proposing some new rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers. In an attempt to deal with people like Ablett, students were forbidden to speak in public without the permission of the executive committee. It was made clear to Henry Sanderson Furniss that he was expected to try and reduce the radicalism in the college. However, as an inexperienced teacher, with little experience of working-class life, he found this very difficult. (10)

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life. (11)

It is believed that 20 students were members of the Plebs League. Noah Ablett organised a students' strike in support of Hird. (12) The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. (13)

Noah Ablett now advocated the establishment of an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. The Central Labour College (CLC) was established later that year, with Hird as its unpaid principal. It was financially supported by the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). (14)

Noah Ablett and Syndicalism

Noah Ablett was a supporter of the syndicalist ideas of Tom Mann, who had started publishing The Industrial Syndicalist in July 1910. (15) In the first edition he argued: "The workers should realize that it is the men who manipulate the tools and machinery who are the possessors of the necessary power to achieve something tangible, and they will succeed just in proportion as they agree to apply concerted action." Mann went on to say that syndicalism was "revolutionary in aim because it will be out for the abolition of the wages system" and "revolutionary in method, because it will refuse to enter into any long agreements with the masters." (16)

Another influence was Daniel De Leon, a leading figure in the Socialist Labor Party in America. "Daniel De Leon believed that workers should form industrial unions to overthrow capitalism, which would in turn provide forms of industrial democracy within a socialist society. Strike action, especially the general strike, held a central place in industrial unionist philosophy." (17)

Noah Ablett remained active in the MFGB and became a member of the South Wales Miners' Federation executive committee in January 1911, and began campaigning against the leadership of MFGB. Kenneth O. Morgan, the author of Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987), suggests that Ablett had encouraged a "fierce revolt amongst working-class students in Oxford against the quietism of Ruskin College". It was also a "revolt at the grass-roots (or rather the pit-head) against the caution" of people such as William Abraham, President of the South Wales Miners' Federation and Treasurer of the MFGB. (18)

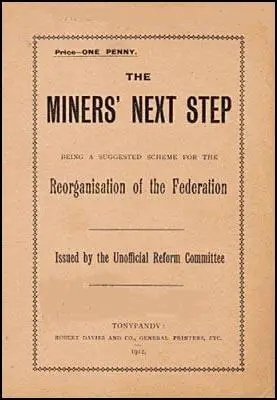

In 1912 Noah Ablett joined forces with Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring to produce the pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step. It stated: "That the organisation shall engage in political action, both local and national, on the basis of complete independence of, and hostility to all capitalist parties, with an avowed policy of wresting whatever advantage it can for the working class... Today the shareholders own and rule the coalfields. They own and rule them mainly through paid officials. The men who work in the mine are surely as competent to elect these, as shareholders who may never have seen a colliery. To have a vote in determining who shall be your fireman, manager, inspector, etc., is to have a vote in determining the conditions which shall rule your working life. On that vote will depend in a large measure your safety of life and limb, of your freedom from oppression by petty bosses, and would give you an intelligent interest in, and control over your conditions of work. To vote for a man to represent you in Parliament, to make rules for, and assist in appointing officials to rule you, is a different proposition altogether." (19)

The pamphlet was attacked by the national press. The Spectator argued: "The present plan of campaign of the Syndicalists both here and in France can only be described as sheer immorality. The advice given to miners in the famous little pamphlet called The Miners' Next Step, to destroy their employers' profits by shirking work, must create a state of mind which would be fatal to any group of co-operators.... The truth is that Syndicalism at this moment must not be judged from the point of view of its philosophic conception of co-operative industries owned and controlled by the persons working in them, but must be looked at primarily as a revolutionary movement... For whereas a Syndicalist strike has for its object the diversion of some of the employer's profits into the workmen's pocket, the method by which this end is to be attained is the infliction of suffering and misery upon persons who have no direct part in the quarrel. That is a method of industrial warfare which no nation can afford to tolerate." (20)

In 1912 Ablett married Annie Howells and they had a son and a daughter. After the outbreak of the First World War was active in the opposition to the conflict. However, he was the only member of the SWMF executive committee prepared to take strike action against the conflict. He supported the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the following year he was elected as miners' agent for Merthyr. (21)

Frank Hodges, the miners' agent for the Garw Valley, was originally a syndicalist. However he was eventually to reject these radical views and preferred the more moderate approach of guild socialism, that was advocated by G. D. H. Cole. In 1918 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), decided to appoint a full-time general secretary. Noah Ablett was nominated for the post but was defeated by the more moderate Hodges. (22)

In 1921 Noah Ablett became a member of the executive committee of the MFGB. Frank Hodges was elected for Litchfield in the 1923 General Election. Under the rules of the union he now had to resign his post as general secretary but he initially refused. It was not until he was appointed as Civil Lord of the Admiralty in the Labour Government that he agreed to go. Ablett attempted to become the new general secretary but Arthur Horner and other Welsh militants, gave their support to Arthur J. Cook and he secured the official South Wales nomination. (23)

Horner later explained: "Ablett was a thoughtful, logical Marxist, who did not bother about personal popularity and who would not fail in anything he decided to try. But I went on to say that I thought he would be inclined to try one path and pursue it to the end. Cook, on the other hand, would examine half a dozen paths, and would try the lot. Perhaps four or even five would fail, but the sixth would win. This, I said, was a time for new ideas. We needed an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure, and I believed Cook was the man." (24)

Cook subsequently won the national ballot by 217,664 votes to 202,297. Fred Bramley, general secretary of the TUC, was appalled at Cook's election. He commented to his assistant, Walter Citrine: "Have you seen who has been elected secretary of the Miners' Federation? Cook, a raving, tearing Communist. Now the miners are in for a bad time." However, his victory was welcomed by Arthur Horner who argued that Cook represented “a time for new ideas - an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure”. (25)

The General Strike

Noah Ablett supported the 1926 General Strike. However, Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Stanley Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (26)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (27)

Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (28)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and the TUC attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (29)

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (30)

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work." (31)

Seven Month Lockout

Arthur Pugh, the President of the Trade Union Congress, and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. Arthur J. Cook asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine". (32)

Bernard Partridge, Secret Ballot (13th October 1926)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain." (33)

Newspapers relentlessly attacked Cook during the lock-out: "The press had hated Cook ever since he was first elected. Now, in the full flow of the lock-out, they brought out all the tricks of the trade to damage him... By use of demonology - the study of the devil - they sought to detach the miners’ leader from the miners. All Cook’s qualities were described as characteristics of the devil. His passionate oratory became demagogy; his unswerving principles became fanaticism; his short, stooping stature became the deformity of some gnome or imp. In particular, Cook’s independence of mind and thought was turned into its opposite. He was the tool of others, the plaything of a foreign power". (34)

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (35)

Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude." (36)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (37)

In November 1926, towards the end of the miners' lock-out, he arranged a local settlement for Hill's Plymouth collieries, to prevent these pits from being shut permanently. "In the ensuing row he assumed responsibility for the agreement even though he had the secret approval of Tom Richards, the general secretary of the SWMF. He was suspended from the executive committee of the SWMF and lost his seat on that of the MFGB. He was also removed as chairman of the governors of the CLC, which had suffered a series of recent scandals. He considered that he had sacrificed his career for the people of Merthyr, although excessive drinking over a long period had already become a major contributory factor in his decline." (38)

Noah Ablett died of cancer on 31st October 1935.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987)

Miners of radical thought in the Rhondda believed the capitalist structure of the coal industry was based on injustice and exploitation; the way forward (in terms of immediate advances and long-term abolition of private ownership) lay through the use of industrial power; but the SWMF was presently incapable, due to its organisation and leadership, of delivering the goods. Such men searched for ideas and strategies to suit the situation they perceived. And they found them. To understand the development of Arthur Cook's philosophy we must examine the attitudes and concepts that were stimulated by events in the Rhondda before 1914. Most of these ideas were brought into those valleys via the actions of one man, the "schoolmaster" of the band of young, talented and politically conscious miners - Noah Ablett. Like Cook, Ablett was born in 1883; like Cook he had been a boy preacher. But Ablett's conversion to socialism was quicker, and in 1907 he was chosen to attend Ruskin College, Oxford, on a scholarship from the Rhondda No. 1 District of the SWMF. There Ablett came into contact with the British Advocates of Industrial Unionism, established in 1906 by the Socialist Labour Party in order to prepare the ground for the establishment of revolutionary trade unions in opposition to existing organisations. On his return to South Wales at the end of his studies, Ablett formed a branch of the BAIU in Porth, distributing industrial unionist literature in the area. The proposal to create new unions did not, however, attract much support amongst miners who were committed to the SWMF even if they were dissatisfied with its leadership and structure. Ablett soon began to move away from the strict BAIU stance and channelled his energies into the radicalisation and reform of the SWMF. He became an early proponent of "industrial syndicalism".

(2) Arthur Horner, Incorrigible Rebel (1960)

Ablett was a thoughtful, logical Marxist, who did not bother about personal popularity and who would not fail in anything he decided to try. But I went on to say that I thought he would be inclined to try one path and pursue it to the end. Cook, on the other hand, would examine half a dozen paths, and would try the lot. Perhaps four or even five would fail, but the sixth would win. This, I said, was a time for new ideas. We needed an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure, and I believed Cook was the man.

(3) The Spectator (30th March, 1912)

The public is beginning to realize the importance of Syndicalism, but still is in doubt as to what Syndicalism means. And. the doubt is excusable. For the term is somewhat vague, and. more than one meaning can legitimately be attached to it. Mr. Lloyd, George, for example, the other day spoke as if Syndicalism were so completely opposed to Socialism that the Socialist might be used as a policeman for the Syndicalist, and vice versa. This certainly is a false conception, as Mr. Lloyd George might easily have discovered for himself by merely observing what is at the moment happening around him. The Syndicalists are admittedly responsible for the appeals which have been made to the soldiers to refuse to fire in the case of a riot arising out of the present strike. If Socialists were prepared to act as policemen here is an obvious case for their activity. Instead of showing the slightest desire to maintain law and order in the interests of the State, the Socialists with one accord, including even the middle-class sentimentalists of the Fabian Society, have protested against the prosecution of Mr. Tom Mann. It would be far truer to say that the Syndicalists form the left wing of the Socialist Party, and though their aims may be far ahead, and in many respects divergent from those of the main body, yet the party as a whole is perfectly willing to lend its support to the Syndicalists wherever the latter come into violent conflict with the existing organization of society. The word "Syndicalism," like the thing itself, comes from France. The word. is derived from synclicat, which is the French name for trade union, and. Syndicalism may best be described. as an ultra-militant form of trade unionism. The pure Syndicalist differs from the average Socialist in this, that whereas the Socialist aspires to create a gigantic system of State-controlled industry the object of the Syndicalist is to allow each trade union to become itself the owner and. controller of the industry in which its members are engaged. For example, in a symposium on Syndicalism, issued. by Mr. Tom Mann in 1910, one of the writers says: "We claim that no 670 men elected to Parliament from various geographical areas can possibly have the requisite technical knowledge to properly direct the productive and distributive capacities of the nation. The men and women who actually work in the various industries should be the persons best capable of organizing them." This is a view with which all individualists can to a large extent sympathize. It is, in fact, nothing but the old ideal of co-operative industry, an ideal which has occupied the minds of social reformers ever since the days of Robert Owen. We will even go so far as to say that it is perhaps the finest ideal which could be pictured. Whether it is realizable is altogether a different question.

(4) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987)

The Welsh miners were ripe for another Messiah. Indeed, the use of religious and eschatological terms comes naturally enough to an analysis of the coalfield at this period. The 1904 religious revival, which galvanized Wales in the next two years from its starting-point at Loughor near Llanelli, had a powerful impact on the consciousness of many young miners. They included men like Frank Hodges, Arthur Cook, Arthur Horner, S. O. Davies, and others moved by religious experience to become part of the vanguard of industrial revolt. One of these was Noah Ablett, the most remarkable Marxist ideologue to surface in any part of the British coalfield in this period. Born to a large mining family at Porth in the Rhondda in 1883, his early enthusiasm was kindled by the community life of the local chapels, and he was soon preaching the gospel in local pulpits. However, a pit accident, which prevented his moving on to a post in the minor civil service, led to his continuing as a working miner underground. Over the next few years, he became fired by the theory of socialism, and of the message of Marx's Kapital in particular. He was an outstanding student at Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1907-9, where he became closely associated with an older Welsh miner and fellow Marxist, Noah Rees. Ablett returned to the Rhondda in 1909 a fierce and learned advocate of extreme socialist views, coloured additionally by the syndicalism of Sorel in France and the industrial unionism of Tom Mann. Ablett was, indeed, a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance. As an educator and ideologue, he was unique.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(2) Geoff Andrews and Hilda Kean, Ruskin College: Contesting Knowledge, Dissenting Politics (1999) page 19

(3) Harold Pollins, The History of Ruskin College (1984) page 9

(4) Henry Sanderson Furniss, Memoirs of Sixty Years (1931) pages 88-90

(5) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(6) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 101

(7) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) page 11

(8) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(9) Andrew Thorpe, Hastings Lees-Smith : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(10) Henry Sanderson Furniss, Memoirs of Sixty Years (1931) page 83

(11) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 101

(12) The Times (3rd August, 1909)

(13) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 103

(14) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(15) Tom Mann, Memoirs (1923) page 206

(16) Tom Mann, The Industrial Syndicalist (January, 1910)

(17) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(18) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 73

(19) Arthur J. Cook, Noah Ablett and William H. Mainwaring, The Miners' Next Step (1912) pages 19-20

(20) The Spectator (30th March, 1912)

(21) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(22) Keith Davies, Frank Hodges : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(23) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 76

(24) Arthur Horner, Incorrigible Rebel (1960) page 43

(25) Frank McLynn, The Road Not Taken: How Britain Narrowly Missed a Revolution (2013) page 395

(26) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) page 99

(27) Julian Symons, The General Strike (1957) pages 198-199

(28) Walter Citrine, Men and Work (1964) page 194

(29) Frank McLynn, The Road Not Taken: How Britain Narrowly Missed a Revolution (2013) page 461

(30) Charles Loch Mowat, Britain Between the Wars (1955) page 332

(31) Anne Perkins, A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) page 199

(32) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) page 99

(33) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) pages 102-103

(34) Paul Foot, An Agitator of the Worst Type (January, 1986)

(35) Anne Perkins, A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) page 255

(36) A. J. Cook, The Miner (28th August, 1926)

(37) Paul Foot, An Agitator of the Worst Type (January, 1986)

(38) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)