Dennis Hird

James Dennis Hird, the second of five sons, was born in Ashby, Lincolnshire, on 28th January 1850. His father, Robert Hird, was a grocer, and was a devout Primitive Methodist. This religious group were sympathetic to the needs of the working-classes and were important in the development of the early trade union movement. (1)

Hird graduated from Oxford University in 1875 and was appointed as a tutor and lecturer to students at the university who were not attached to individual colleges. In December 1884, Hird was ordained as a Church of England deacon and appointed to St Michael and All Angels Church in Bournemouth. The following year he was appointed curate of Christ Church in Battersea, where he served one of the poorest districts in London. "In this position he worked strenuously for the poor and the outcast, raising many thousands of pounds for the distressed." (2)

In 1887 Hird was appointed as General Secretary of the Church of England Temperance Society in London. However, the authorities became concerned when in 1893 he joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and began arguing for the improvements in the education of the working class. The Bishop of London, Frederick Temple, wrote: "Mr Hird must either quit them or quit us." In the Bishop's view socialism would destroy the liberty of the individual and when Hird refused to leave the SDF he was dismissed from his post. (3)

Dennis Hird was also part of the Christian Socialist movement that played an important role in the development of the labour movement. Other supporters included Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, Katharine Glasier, Margaret McMillan and Rachel McMillan. The church authorities decided to get him out of London and Lady Isabella Somerset, agreed to help by appointing him rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor. (4)

In January 1895 Dennis Hird gave a talk about "Jesus the Socialist" that caused a great scandal. "The agricultural laborer has given religion up, the artisan does not want it, the city business man has no time for it, and the rich? well, they are happy enough without it. Now, in face of these facts, does it not strike you as strange that the Son of God should come to the world and not be able to discover a form of government or a religion which could heal the world? But before you condemn Him, be sure that you know what the religion of Jesus is, and be sure that it has been tried." (5)

Hird also wrote a novel in the style of Jonathan Swift, "a biting satire on England" entitled Toddle Island: Being the Diary of Lord Bottsford. This was followed by another novel, A Christian with Two Wives (1896), a humourous account of those "who believed in the infallibility of the Bible from cover to cover". Lady Somerset now decided that "her unruly rector must go" and he was dismissed. Hird now had to sell his library to provide support for his family. (6)

Dennis Hird and Ruskin College

In February, 1899 Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established Ruskin Hall (later known as Ruskin College), a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people. The two men received most of their funds from their two wealthy wives, Mary Beard and Amne Vrooman. (7) It was named after the essayist John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had written extensively about adult education. (8) The idea was that "economics and sociology should be taught from the working-class point of view, although not to the exclusion of the official capitalist standpoint, if that was thought desirable". (9)

Ruskin Hall was also called a "College of the People" and the "Workman’s University". It was to be a residential institution providing study opportunities for a whole year or for shorter periods as appropriate. The residential element of the College’s work in its early years was open to men only. Harold Pollins pointed out: "It was to be part of a nationwide movement in order to cater for the large number who wanted to study but would not be able to take time off work. Provision for them, women as well as men, would be in two parts: correspondence courses, and extension classes in their own localities taught by the Ruskin Hall Faculty and by other lecturers." (10)

Walter Vrooman, who admired the way Dennis Hird had sacrificed his career in order to defend his socialist beliefs, decided to appoint him as the the college's first principal. By the end of the year the college had fifty-five students. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power." (11)

The students, almost all of them sent on trade union scholarships worth £52. Some of the early students included Edward Traynor (a Yorkshire miner who had lost a leg in a accident at work), Robert Carruthers (a former railway booking clerk and a soldier in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers), Frank Merry (a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and secretary to Walter Vrooman), Joseph Heywood (an apprentice journalist on the Manchester Guardian) and Horace J Hawkins (a member of the Social Democratic Federation who was expelled from the college in November, 1899). The students were expected to carry out nearly all of the domestic duties, the cooking, serving, washing up the duties and the general cleanliness. (12)

Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established a Council to run Ruskin College. It consisted mainly of university men, whom he thought in sympathy with the ideals he set for the educational work on the institution. Three trade unionists, Richard Bell, General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, David Shackleton, the leader of the Weavers' Union and General Secretary of the London Society of Compositors, Charles W. Bowerman, also served on the Council.

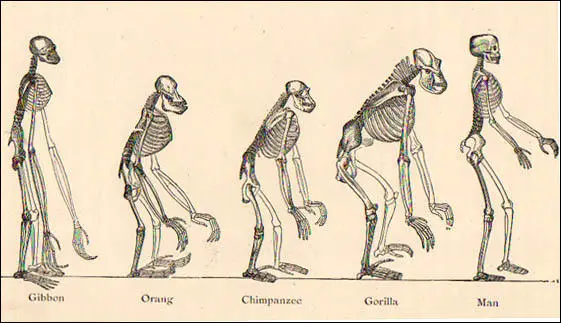

At the college Dennis Hird taught sociology, organic evolution and formal logic. This meant that Hird was teaching sociology to his students at Ruskin College nearly 50 years before it was officially recognised by the University of Oxford. During these sessions he introduced his students to the work of Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Émile Durkheim.

Hird also published a book explaining and popularising the theory of evolution, The Picture Book of Evolution (1906). He argued that the publishing of Darwin's book, The Origin of Species (1859) was "one of the greatest events in the history of mankind, for it has altered the thoughts of the world and killed many errors". Hird goes on to say that "with regard to living things - plants and animals - Evolution teaches that they all have come by descent from small early forms which were so simple and tiny that no one can say whether they were plants or animals." (13)

Dennis Hird was especially interested in promoting the work of the sociologist, Frank Lester Ward, a supporter of female and racial equality, who argued that poverty could be minimized or eliminated by the systematic intervention of the government. His work was very controversial and was banned in several countries, including Russia. Although his lectures on Ward was popular with the students they upset senior figures at Oxford University. One academic commented that before "Frank Lester Ward could begin to formulate that science of society which he hoped would inaugurate an era of such progress as the world had not yet seen, he had to destroy the superstitions that still held domain over the mind of his generation. Of these, laissez-faire was the most stupefying, and it was on the doctrine of laissez-faire that he trained his heaviest guns." (14)

Hird's teaching had a major impact on the students: "Dennis Hird was the only member of the resident lecture staff who could, and did, help us to gain some scientific knowledge about the world and man's place in it. Most of us, before we came to Ruskin, accepted the theory of evolution, the descent of man from the animal world, although it was a viewpoint still shared by only a minority of the British people, and only by a few in the academic life of Oxford. Hird greatly enriched our knowledge of the work of the great biologist Darwin, and his scientific theory of the origin of species.... The next problem we had to consider was how the different species of social organisation had arisen and changed in the human struggle for existence. We found the answer to that question in the works of a contemporary of Charles Darwin, the great German sociologist, Karl Marx.... It would have been difficult to express adequately in words the glowing feeling of an immense liberation kindled in our minds by those new views of man and his work. It was almost as if we had discovered a new world, although actually it was the discovery of the old world in the new light of a rich and revealing knowledge." (15)

In addition to Hird, three other lecturers were appointed by Walter Vrooman. Hastings Lees-Smith, who also served as vice-principal, Bertram Wilson, who became general secretary of the college, and Alfred Hacking, a friend and supporter of Hird, who was placed in charge of the correspondence students. The students, almost all of them sent on trade union scholarships worth £52. (16)

Hastings Lees-Smith disagreed with the politics of Hird. He was educated for an army career, first at the Aldenham School and then at the Royal Military Academy, but as a result of "a weak constitution" he left to join Queen's College. In 1899 he graduated with second-class honours in history. A member of the Liberal Party he taught economics and as he was a supporter of the free-market he upset the socialist students at Ruskin. (17)

After two years Amne Vrooman, who had divorced her husband, stopped funding Ruskin College. The general secretary of the college, was forced to seek donations from private individuals. Bertram Wilson, General Secretary of Ruskin College sent out letters explaining why they needed donations: "Madam, I hope I am doing right in bringing Ruskin College to your notice. It was founded eight years ago with the object of giving workingmen a sound practical knowledge of subjects which concern them as citizens, thus enabling them to view social questions sanely and without unworthy class bias." (18)

Most of the people who provided the funding of the college did not share the political beliefs of Hird. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power." (19)

Robert Carruthers (top, third left), Bertram Wilson (top, eighth left), George Sims

(middle, first left), Dennis Hird (middle, fourth left), Frank Merry (middle, sixth left)

and Joseph Heywood (middle, seventh left).

The students became increasingly disturbed by the economic teaching of Hastings Lees-Smith. At the time the Miners' Federation of Great Britain were attempting to negotiate with the Coal Owners Association a minimum wage for its members. Lees-Smith used his lectures to condemn this strategy on the grounds that it would cause unemployment and reduced investment. Sidney Webb, the Labour Party politician, advocating the minimum wage, was accused of telling "a tissue of lies". (20)

One of the students, J. M. K. MacLachlan, a member of the Independent Labour Party, wrote an article for the September edition of Young Oxford: "The present policy of Ruskin College is that of a benevolent trader sailing under a privateer flag. Professing the aims dear to all socialists, she disavows those very principles by repudiating socialism. Let Ruskin College proclaim socialism; let her convert her name from a form of contempt into a canon of respect." (21)

Noah Ablett, a member of the South Wales Miners' Federation, began a course at Ruskin College in 1907. He was completely self-educated and after reading the works of Karl Marx, Daniel De Leon and Tom Mann, he was a committed socialist. According to his biographer, Hywel Francis, "he quickly made his mark on educational thinking at Ruskin, and organized classes in Marxian economics and history as an alternative to the traditional liberal curriculum". (22)

Bernard Jennings argues that Ablett had a considerable influence over the students at Ruskin: "Tensions began to build as increasing numbers of students became ardent socialists. They enjoyed Hird's lectures on sociology, a major element of which was the study of evolution, on which he had written a popular book. They disliked Lees Smith's lectures on economics, although acknowledging his ability as a teacher, because his adherence to current free-market theories was just as dogmatic as that of the left-wing students to Marxism." (23)

In 1907 Hastings Lees-Smith, who was later to become a Liberal Party MP, was appointed professor of economics at University College, but he did not relax his grip on Ruskin. He became chairman of Ruskin College's executive committee and was chief adviser on studies. He now had control over staff recruitment and appointed, Charles Stanley Buxton, aged 23 as vice-principal. His father was Charles Sydney Buxton, the President of the Board of Trade. (24)

Lees-Smith also recruited Henry Sanderson Furniss to lecture on economics, who both shared his view "of the relationship between class improvement and education". Sanderson Furniss came to realise that he and Buxton were intended to carry on Lees Smith's campaign against Hird: "They were, however, ill-equipped to do so, or to provide an antidote to the Marxist ideas which Furniss criticised without knowing much about them. They knew little about teaching, and less about working-class life." (25)

Although Dennis Hird was the Principal of Ruskin College, he was not consulted on these appointments. On his appointment his duties were defined as "to be in charge at Ruskin Hall". However, this was later changed to say all decisions were to be made by a House Committee of three, consisting of the Principal, the Vice-Principal and the General Secretary of the College. Buxton and Sanderson Furniss now joined forces to constantly outvote Hird. (26)

Christian Socialist

Dennis Hird remained one of the leaders of the Christian Socialist movement. In 1908 he published a pamphlet, Jesus the Socialist, that was based on the speech he delivered in 1896, that resulted in him losing his post as rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor. The pamphlet sold over 70,000 copies. (27)

Hirds begins the pamphlet with a quote from Henry Hart Milman, the former Dean of St. Paul's: "Christianity has been tried for more than eighteen hundred years: perhaps it is time to try the religion of Jesus.” Hird comments: "That is a pressing question. Is Christianity, as now usually practised and taught, the same thing as the religion of Jesus? I maintain emphatically that it is not!"

Hird admitted that one of his concerns was that the poor appeared to be rejecting Christianity. His answer to this problem was to show them that Jesus advocated socialism. "Was Jesus a Socialist? It is true He was never called a Socialist; it is also true He was never called a Methodist, or a Baptist, or a Papist, or a Church of England man; thank God, He was called by none of these names. It is true He never saw a Socialist; it is also true that He never saw a bishop or a pope."

Hird then went on to look at the teachings of the son of God. "Jesus said: 'Thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself' (Matthew 19:19 and 22:39). I know no definition of Socialism to equal this 'Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.' You are familiar with this quotation which Jesus made from (Leviticus 19:18), so familiar with it that perhaps you have thought it was an original utterance by Jesus. We must remember the method employed by Jesus. He gave us no system of thought, no creed, no cut-and-dried dogmas, no church organizations: He unfolded great principles, and many of those were not new, but were set forth with new vigor and forcible illustrations."

Dennis Hird attempted to explain why the Church had not stayed true to the teachings of Jesus: "It is so much easier to worship Christ than to imitate Jesus, that men have taken up the worship, and I think some of them verily believe, when they confess their sins by the aid of a choir, or sing their hymns in fairly good harmony, that God is pleased with the sweet music. Jesus sought men to imitate him rather than to worship Him.... That is a very different thing from listening to a choral service on a Sunday morning, and giving a small check to the curate fund. Jesus seeks imitation, not adulation. A far-away heaven, with a far-away God, enveloped in a far-away glory, is no use to this world, and certainly is no part of the teaching of Jesus." (28)

Sacking of Dennis Hird

Noah Ablett, the most left-wing of Ruskin's students, set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In October 1908, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. The objective of the Plebs League was "to bring about a definite and more satisfactory connection between Ruskin College and the Labour Movement". (29)

Membership of the organisation was open to all resident and correspondence students, past and present, on the payment of 1s. per year. Over the next few weeks branches were established in five towns in the Welsh coalfield. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits to these classes. (30) Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique". (31)

In November 1908, Oxford University announced that it was going to take over Ruskin College. The chancellor of the university, George Curzon, was the former Conservative Party MP and the Viceroy of India. His reactionary views were well-known and was the leader of the campaign to prevent women having the vote. Curzon visited the college where he made a speech to the students explaining the decision. (32)

Dennis Hird replied to Curzon: "My Lord, when you speak of Ruskin College you are not referring merely to this institution here in Oxford, for this is only a branch of a great democratic movement that has its roots all over the country. To ask Ruskin College to come into closer contact with the University is to ask the great democracy whose foundation is the Labour Movement, a democracy that in the near future will come into its own, and, when it does, will bring great changes in its wake".

The author of The Burning Question of Education (1909) reported: "As he concluded, the burst of applause that emanated from the students seemed to herald the dawn of the day Dennis Hird had predicted. Without another word, Lord Curzon turned on his heel and walked out, followed by the remainder of the lecture staff, who looked far from pleased. When the report of the meeting was published in the press, the students noted that significantly enough Dennis Hird's reply was suppressed, and a few colourless remarks substituted." (33)

William Craik, a member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (later the National Union of Railwaymen) pointed out that his fellow students were "very perturbed at the direction in which the teaching and control of the College was moving, and by the failure of the trade union leaders to make any effort to change that direction. We new arrivals had little or no knowledge of what had been taking place at Ruskin before we got there. Most of us were socialists of one party shade or other." (34)

Noah Ablett emerged as the leader of the resistance to the plans of Hastings Lees-Smith. A coalminer from South Wales, he was one of the Ruskin students who was greatly influenced by the teachings of Dennis Hird. He set up Marxist tutorial classes in the central valleys of the Welsh coalfield. In January 1909, Ablett and some of his followers established the Plebs League, an organisation committed to the idea of promoting left-wing education amongst workers. Over the next few weeks branches were established in five towns in the coalfield. Arthur J. Cook and William H. Mainwaring were two early recruits to these classes. (35) Ablett was described as "a remarkable young man, a rebel of cosmopolitan, perhaps cosmic, importance" and "as an educator and ideologue, he was unique". (36)

Students of Ruskin College were forbidden to speak in public without the permission of the executive committee. In an effort to marginalise Dennis Hird, new rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers were introduced. "This met with strong resistance from the majority of the students, who looked upon it as one more way of making the connection with the University still closer... Most of the students had come to Ruskin College on the understanding that there would be no tests other than monthly essays set and examined by their respective tutors, and afterwards discussed in personal interviews with them." (37)

In August 1908, Charles Stanley Buxton, the vice-principal of Ruskin College, published an article in the Cornhill Magazine. He wrote that "the necessary common bond is education in citizenship, and it is this which Ruskin College tries to give - conscious that it is only a new patch on an old garment." (38) It has been argued that "it read as if it had been written by someone who looked upon the workers as a kind of new barbarians whom he and his like had been called upon to tame and civilise". (39) The students were not convinced by this approach as Dennis Hird had told them about the quotation of Karl Marx: "The more the ruling class succeeds in assimilating members of the ruled class the more formidable and dangerous is its rule." (40)

Lord George Curzon published Principles and Methods of University Reform in 1909. In the book he pointed out that it was vitally important to control the education of future leaders of the labour movement. He urged universities to promote the growth of an elite leadership and rejected the 19th century educational reformers call for reform on utilitarian lines to encourage "upward movement" of the capitalist middle class: "We must strive to attract the best, for they will be the leaders of the upward movement... and it is of great importance that their early training should be conducted on liberal rather than on utilitarian lines." (41)

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life. (42)

It is believed that 20 students were members of the Plebs League. Its leader, Noah Ablett organised a students' strike in support of Hird. Another important figure was George Sims, a carpenter, who had been sponsored by Albert Salter, a doctor working in Bermondsey who was also a member of the Independent Labour Party. He was the man chosen to deal with the press. (43)

The Daily News reported: "It is one of the quaintest of strikes, this revolt of the 54 students of Ruskin College against what they consider the intolerable action of the authorities with regard to Mr. Dennis Hird, the Principal." In an interview with one of the strikers, George Sims claimed that the students had been told by the authorities that Hird had been sacked because he had been "unable to maintain discipline". The real reason was the way that Hird had been teaching sociology. (44)

On 2nd April the newspaper carried an interview with Dennis Hird: "I have received hundreds of letters of sympathy from past students....There can be no foundation of any sort, technical or otherwise, for the statement that I have failed to maintain discipline. The fact that I have the love of hundreds of students, past and present, and that they would do anything for me, is surely the answer to that." The journalist added "the workingmen students of Ruskin College were as determined as ever that under no circumstances would they consent to Mr. Hird's going.... As matters stand at present it is clear that only the reinstatement of Mr. Hird can save serious trouble." (45)

The following day the newspaper carried an editorial on the dispute: "We are far from wishing to take any side in the controversy, but the unanimity of the students in their support of Mr. Hird, the dismissed Principal, is a fact which cannot be ignored. It may be that the students are mistaken as to the reason for his dismissal, but there is no doubt of the genuine affection they have for their Principal and the reality of their conviction that his dismissal is associated with an organic change in regard to the College.... Ruskin College is an effort to permeate the working classes with ideals and culture, which, while elevating and benefiting the students, will not divorce them from their own atmosphere but will serve to make that atmosphere purer and better." (46)

The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin College at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. However, the students decided that they would use the Plebs League and its journal, the Plebs' Magazine, to campaign for the setting up of a new and real Labour College. (47)

The Central Labour College

Dennis Hird received very little support from other advocates of working-class education. Albert Mansbridge, the

founder of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) in 1903, blamed Hird's preaching of socialism for his dismissal. In a letter to a French friend, he wrote "the low-down practice of Dennis Hird in playing upon the class consciousness of swollen-headed students embittered by the gorgeous panorama ever before them of an Oxford in which they have no part." (48)

Noah Ablett took the lead in establishing an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. George Sims, who had been expelled after his involvement in the Ruskin strike, played an important role in raising the funds for the project. On 2nd August, 1909, Ablett and Sims organised a conference that was attended by 200 trade union representatives. Dennis Hird, Walter Vrooman and Frank Lester Ward were all at the conference. (49)

Sims explained that the "last link which bound Ruskin College to the Labour Movement had been broken, the majority of the students had taken the bold step of trying to found a new college owned and controlled by the organised Labour Movement." (50) Ablett moved the resolution: "That this Conference of workers declares that the time has now arrived when the working class should enter the educational world to work out its own problems for itself." (51)

The conference agreed to establish the Central Labour College (CLC). The students rented two houses in Bradmore Road in Oxford. It was decided that "two-thirds of representation on Board of Management shall be Labour organisations on the same lines as the Labour Party constitution, namely, Trade Unions, Socialist societies and Co-operative societies." Most of the original funding came from the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). (52)

Dennis Hird agreed to act as Principal and to lecture on sociology and other subjects, without any salary. George Sims worked as its secretary and Alfred Hacking was employed as tutor in English grammar and literature. Fred Charles accepted a post as tutor in industrial and political history. The teaching staff was supplemented by regular visiting lecturers, such as Frank Horrabin, Winifred Batho, Rebecca West, Emily Wilding Davison, H. N. Brailsford, Arthur Horner and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. In 1910 William Craik was appointed as Vice-Principal.

In 1911 the college moved to London. "Very soon after the College arrived in Kensington it began to conduct evening classes, both within and without, for the working men and women in the district, and to extend their range. Not many years were to pass before there was hardly a suburb in Greater London without one or more Labour College classes at work in it. Nothing like this, needless to say, would have been possible had the College remained in Oxford." (53)

John Saville has argued that the Central Labour College provided the kind of socialist education that was not provided by Ruskin College and the Workers' Educational Association. "What we have in these years is both the attempt to channel working-class education into the safe and liberal outlets of the Workers' Educational Association and Ruskin College, and the development of working-class initiatives from below; and it is the latter only which made its contribution to the socialist movement - and a considerable contribution it was." (54)

Bernard Jennings agrees with Saville on this point and points out that Richard Tawney, A. D. Lindsay and Archbishop William Temple were all supporters of Ruskin College and the WEA over the Central Labour College: "There is no doubt that the establishment preferred the WEA and Ruskin to the Labour college movement, a fact exploited quite brazenly by the WEA in the 1920s. Temple, Tawney and A. D. Lindsay all warned the Board of Education and the LEAs that unless they supported the WEA and respected its academic freedom, workers' education would fall to the CLC." (55)

The Central Labour College was always short of money. The Plebs Magazine was used to raise funds. "Your cash will be used to good purpose - make no doubt of that. The CLC flag has been kept flying up to now by the pluck, devotion and enthusiasm of the garrison. Only those, perhaps, who - like the present writer - have had an occasional glimpse behind the scenes, know the extent of the devotion and that enthusiasm. What are you going to do about it?" (56)

Dennis Hird suffered for many years with thrombosis. He became very ill in 1913 and was confined to his bed for over a year. He returned to work in 1914 but in May 1915 he was forced back to his bed. William Craik and George Sims took over most of his details. However, Craik and Sims were conscripted into the British Army in 1917 and it was forced to close until the end of the First World War. (57)

One of Hird's former students visited him in 1919 and "despite the tediousness of his prolonged confinement in bed, he was cheerful and quite hopeful of being able to return to his post." Unfortunately he did not recover and died on 13th July 1920. William Craik replaced him as Principal of the Central Labour College. (58)

Primary Sources

(1) Dennis Hird, Jesus the Socialist (1908)

There is no greater marvel among men than that any poor man should not love Jesus, and yet how few of the poor find any real help in Him now.

My lecture can only be a sketch, and will be of no use unless you are going to examine the subject for yourselves. I will abstain from quoting great names, and confine myself to the Bible.

It is no part of my business to defend any particular socialistic scheme, or indeed Socialism itself. A few months ago a lady and a gentleman frankly avowed that to say that Jesus was a Socialist was blasphemous, and that it was a disgrace to a clergyman of the Church of England to say so, and the audiences who listened to these enlightened leaders of profound thought shouted "Down with him (Dennis Hird)." Now as that was the kind of thing the mob of the gentry shouted about Jesus, I felt cheered when I heard of it....

Was Jesus a Socialist? It is true He was never called a Socialist; it is also true He was never called a Methodist, or a Baptist, or a Papist, or a Church of England man; thank God, He was called by none of these names. It is true He never saw a Socialist; it is also true that He never saw a bishop or a pope.

What then, is Socialism? State Socialism is a national scheme of cooperation managed by the State. Most forms of socialism demand that the land and other instruments of production shall be the common property of the people, and shall be used and governed by the people for the people. In other words, "Socialism is equality of privilege for every child of man."

But you say that this is contrary to nature, it is impossible, it is the wild dream of a madman. Well, all this may be true. Certainly those who heard Jesus thought He was a madman, and said so (Mark 3:21).

But that is not our question: Did Jesus teach and live out principles such as now find their embodiment under the word Socialism?

Jesus said, "Thou shall love thy neighbor as thyself" (Matthew 19:19 and 22:39). I know no definition of Socialism to equal this "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” You are familiar with this quotation which Jesus made from (Leviticus 19:18), so familiar with it that perhaps you have thought it was an original utterance by Jesus.

We must remember the method employed by Jesus. He gave us no system of thought, no creed, no cut-and-dried dogmas, no church organizations: He unfolded great principles, and many of those were not new, but were set forth with new vigor and forcible illustrations.

We cannot say this too frequently that Jesus gave principles - life-giving principles - and not dead rules. But, above all, we must be clear upon the fact that those principles were to act in this life and to regenerate this world.

Some think that Jesus came to make a few people ready for heaven. I find no such teaching in His words. It is here, in this struggling world, that there is go be the kingdom of God or there is no kingdom of God.

It is so much easier to worship Christ than to imitate Jesus, that men have taken up the worship, and I think some of them verily believe, when they confess their sins by the aid of a choir, or sing their hymns in fairly good harmony, that God is pleased with the sweet music. Jesus sought men to imitate him rather than to worship Him. "If any man will be my disciple, let him take up his cross and follow me." That is a very different thing from listening to a choral service on a Sunday morning, and giving a small check to the curate fund. Jesus seeks imitation, not adulation. A far-away heaven, with a far-away God, enveloped in a far-away glory, is no use to this world, and certainly is no part of the teaching of Jesus.

Take the Lord's Prayer (Matthew 6: 9-13, Luke 11: 2-4), which you say so often, but not in the words He taught you. Even that has been doctored to suit the palate of sickly Christians. That prayer breaks out with the confession that we are all brothers, and to prevent any mistake says, "Thy will be done on earth," and its first request is "Give us this day our daily bread" - the great bread cry of the human family stands before all else, "and forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors"–this is carrying Christianity into the shop and the market-place: it is dreadfully real. "Forgive us our debts" is a matter of fact; "forgive us our trespasses" is a matter of words, and was not used by Jesus. "Lead us not into trial." I do not know what this means, but it certainly cannot mean that God might lead a man into sin; that would be to turn the world topsy-turvy. "But deliver us from evil"; and is there a greater evil than selfishness? The rest of the prayer, as commonly used, was, perhaps, not given by Jesus, but way added by someone else.

Now observe in the prayer, as given by St. Matthew, there is no mention of our going to live in heaven, but we are to do the divine will on earth; there is no mention of sin, but of bread; we are not asked to forgive somebody who has offended our pride, but to forgive him what he owes us. Thus read, the prayer becomes the cry of the poor.

(2) Janet Vaux, The First Students at Ruskin College (27th May, 2016)

The college, which at that time was known as Ruskin Hall, had been founded in 1899 by three visiting Americans (Walter and Amne Vrooman and Charles Beard), who had conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power.

The different political currents of the period were reflected in debates about and within the college. By 1909, differences about college governance and the syllabus (especially the teaching of the theory of evolution and of Marxism), as well as increasingly poisonous relations among the college staff, led to the sacking of Dennis Hird, a student strike, and the setting up of the Central Labour College by the striking students, with Hird as its first principal.

(3) Colin Waugh, The Lost Legacy of Independent Working-Class Education (January 2009)

Vrooman and Beard appointed a fairly high profile left-wing socialist, Dennis Hird, as the principal of Ruskin, and another, Alfred Hacking, as lecturer in charge of correspondence courses. (There were only four full time staff in the beginning.)

Hird was an Oxford graduate (1875). In 1878 he was ordained as an Anglican priest and appointed as a tutor and lecturer to students of Oxford University who were not attached to individual colleges. From 1885-87, he was a curate in Bournemouth, and them moved to Battersea, where in 1888 he joined the (Marxist) Social Democratic Federation

(SDF). While there, he also became secretary of the Church of England Temperance Society for the London diocese. However, in 1893, the Bishop of London, Frederick Temple, found out about Hird`s socialist activities and forced him to resign from this Temperance Society position. In 1893, Lady Henry Somerset appointed Hird to a church living at

Eastnor in Gloucestershire. But in 1896, after he had given a talk about "Jesus the Socialist", she colluded with the bishop for that area to make him renounce his orders. This meant he could no longer earn a living as a clergyman. (Published as a pamphlet, Hird`s talk sold 70,000 copies.) By the time of the 1908-09 events at Ruskin, Hird had

renounced formal Christianity itself.Working class students at Ruskin came to respect Hird so much that early issues of The Plebs Magazine carried adverts for plaster busts of Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Hird himself. Years later some former students still had these on their mantelpieces. As principal of Ruskin, Hird wrote to the British Steel Smelters Association to say that: "Many unions would be glad of an opportunity to send one of their most promising younger members for a year`s education in social questions". This gives us an important clue about what he thought the college was for. However, although Vrooman was a socialist, he was also a Christian, from a well-off nonconformist background. His main rebellion against this background had taken place at 13, when he took himself out of school. The US socialist publisher Charles Kerr was later to say of him that, although he possessed "the greatest enthusiasm for socialism

as he understands it, Vrooman is hopelessly erratic... he wants to be a dictator in whatever he is doing".By deciding to name their project after John Ruskin, Beard and the Vroomans showed that they wanted it to challenge the existing order, but also that, like the Guild of St George founded by Ruskin himself, its focus would be ethical as much as economic. They timed the inaugural meeting for Ruskin Hall in Oxford to coincide with John

Ruskin`s 80th birthday. At this meeting Vrooman described his aim in this way: "We shall take men who have been merely condemning our social institutions, and will teach them instead how to transform those institutions, so that in place of talking against the world, they will begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world, to refashion it, and to cooperate with the power behind evolution in making it a joyous abode of, if not a perfected humanity, at least a humanity earnestly and rationally striving towards perfection". These words reveal Vrooman`s intention that the world should be changed by action from below ("begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world... and to refashion it"). But they also reflect his religious feelings ("the power behind evolution", and the suggestion that humanity cannot be perfected) and his wish to prevent discontent getting out of hand.

(4) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964)

Dennis Hird was the only member of the resident lecture staff who could, and did, help us to gain some scientific knowledge about the world and man's place in it. Most of us, before we came to Ruskin, accepted the theory of evolution, the descent of man from the animal world, although it was a viewpoint still shared by only a minority of the British people, and only by a few in the academic life of Oxford. Hird greatly enriched our knowledge of the work of the great biologist Darwin, and his scientific theory of the origin of species. We were now able to understand more clearly than before the problem and the solution to it presented by Charles Darwin. The problem was how animal and vegetable species originated and survived in the struggle for existence. He found the explanation of their origins and survival in the adaptation of their organisms to the conditions of their environments-not where his predecessor in this sphere of inquiry thought he found it, in survival tendencies inherent in their animal and plant natures.The next problem we had to consider was how the different species of social organisation had arisen and changed in the human struggle for existence. We found the answer to that question in the works of a contemporary of Charles Darwin, the great German sociologist, Karl Marx. From Marx we learned that the evolution of human society had taken place not as the result of some innate tendency in social man, called "human nature", but as the result of social characteristics acquired in the changing ways in which man in the material process of his work acted upon and changed his external environment. "As man acts upon nature and changes it he at the same time changes his own nature."

Darwin brought our knowledge far enough forward for us to understand that "man could not have attained his present dominant position in the world without the use of his hands, which are so adapted to act in obedience to his will", those human hands which have played such a remarkable part in promoting the successes of his brain. What Marx taught us was that man did not come up from the simple field of nature empty-handed, that it was by learning to add new organs to his natural ones, by making himself tool-handed, that he was able slowly to leave that simple field of nature by modifying it through his work. In the beginning was work, and by and through his work, the work of his hands and of his brain, man became man. In that sense man made himself.

It would have been difficult to express adequately in words the glowing feeling of an immense liberation kindled in our minds by those new views of man and his work. It was almost as if we had discovered a new world, although actually it was the discovery of the old world in the new light of a rich and revealing knowledge.

(5) W. H. Steed, The Burning Question of Education (1909)

The students were all standing and had formed a ring, in the centre of which Lord Curzon spoke. Mr. Hird also advanced to the centre and stood facing Lord Curzon while he replied. The contrast between the two men was very striking. The circumstances in which they met invested the event with a distinctly dramatic colour. Lord Curzon wearing his Doctor of Laws gown - not the glittering robes of the Chancellor's office, but robes of dark coloured cloth devoid of ornamentation, as if they represented the University in mourning for the condescension implied in his visit. Not so Lord Curzon himself, however. He stood in a position of ease, supporting himself by a stick, which he held behind him as a prop to the dignity of the upper part of his body. A trifling superiority in height, increased by the use of the stick, allowed him to look down somewhat on Mr. Hird. It was easy to see that this man had been a Viceroy of India. Autocratic disdain, and the suggestion of a power almost feudal in its character, seemed stamped on his countenance.

As the purport of Mr. Hird's reply reached his comprehension, Lord Curzon seemed to freeze into a statuesque embodiment of wounded dignity. For Mr. Hird was not uttering the usual compliments, but was actually rebuking the University for having neglected Ruskin College until the day of its assured prosperity. As he spoke, the students moved instinctively towards him as if mutely offering him support. Mr. Hird, who had begun with flushed cheeks and a slight tremor in his voice, now seemed inspired with an enthusiasm and dignity that only comes to a man who voices the highest aspirations of a great Movement.

In substance, he said: "My Lord, when you speak of Ruskin College you are not referring merely to this institution here in Oxford, for this is only a branch of a great democratic movement that has its roots all over the country. To ask Ruskin College to come into closer contact with the University is to ask the great democracy whose foundation is the Labour Movement, a democracy that in the near future will come into its own, and, when it does, will bring great changes in its wake".

As he concluded, the burst of applause that emanated from the students seemed to herald the dawn of the day Dennis Hird had predicted.

Without another word, Lord Curzon turned on his heel and walked out, followed by the remainder of the lecture staff, who looked far from pleased. When the report of the meeting was published in the press, the students noted that significantly enough Dennis Hird's reply was suppressed, and a few colourless remarks substituted. Very soon afterwards the Principal was made to feel that he had committed the unforgivable sin.

(6) The Daily News (3rd April, 1909)

We are far from wishing to take any side in the controversy, but the unanimity of the students in their support of Mr. Hird, the dismissed Principal, is a fact which cannot be ignored. It may be that the students are mistaken as to the reason for his dismissal, but there is no doubt of the genuine affection they have for their Principal and the reality of their conviction that his dismissal is associated with an organic change in regard to the College.... Ruskin College is an effort to permeate the working classes with ideals and culture, which, while elevating and benefiting the students, will not divorce them from their own atmosphere but will serve to make that atmosphere purer and better.

References

(1) Holliday Bickerstaffe Kendall, The Origin and History of the Primitive Methodist Church (1906) pages 429-432

(2) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 37

(3) Colin Waugh, The Lost Legacy of Independent Working-Class Education (January 2009)

(4) John Beatson-Hird, Dennis Hird: Socialist Educator and Propagandist, First Principal of Ruskin College (1999)

(5) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 101

(6) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 38

(7) Dennis Hird, Jesus the Socialist (1908)

(8) Howard Kennedy Beale, Charles A. Beard: An Appraisal (1954) page 214

(9) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 35

(10) Charles A. Beard, The New Republic (5th August, 1936)

(11) Harold Pollins, The History of Ruskin College (1984) page 9

(12) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 37

(13) Dennis Hird, The Picture Book of Evolution (1906) page 12

(14) Henry Steele Commager, Lester Frank Ward and the Welfare State (1967) page xviii

(15) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 54

(16) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 37

(17) Andrew Thorpe, Hastings Lees-Smith : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(18) Bertram Wilson, standard letter sent out to possible sponsors of Ruskin College (1902)

(19) Janet Vaux, The First Students at Ruskin College (27th May, 2016)

(20) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 44

(21) J. M. K. MacLachlan, Young Oxford (September, 1901)

(22) Henry Sanderson Furniss, Memoirs of Sixty Years (1931) pages 88-90

(23) Hywel Francis, Noah Ablett : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(24) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 51

(25) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 101

(26) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 52

(27) Colin Waugh, The Lost Legacy of Independent Working-Class Education (January 2009)

(28) Dennis Hird, Jesus the Socialist (1908)

(29) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 62

(30) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) page 11

(31) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(32) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 102

(33) W. H. Steed (editor), The Burning Question of Education (1909) page 11

(34) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 52

(35) Paul Davies, A. J. Cook (1987) page 11

(36) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(37) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 54

(38) Charles Stanley Buxton, Cornhill Magazine (August 1908)

(39) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 57

(40) Karl Marx, Pre-Capitalist Relationships (1894)

(41) George Curzon, Principles and Methods of University Reform (1909) page 67

(42) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 103

(43) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 79

(44) The Daily News (31st March, 1909)

(45) The Daily News (2nd April, 1909)

(46) The Daily News (3rd April, 1909)

(47) Brian Simon, Education and the Labour Movement (1974) page 325

(48) Albert Mansbridge, letter to G. Riboud (April, 1909)

(49) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 82

(50) George Sims, speech (2nd August, 1909)

(51) Noah Ablett, speech (2nd August, 1909)

(52) Kenneth O. Morgan, Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants (1987) page 72

(53) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 101

(54) John Saville, The Labour Movement in Britain (1988) page 32

(55) Bernard Jennings, Friends and Enemies of the WEA, included in Stephen K. Roberts, (editor), A Ministry of Enthusiasm (2003) page 105

(56) Frank Horrabin, The Plebs Magazine (February, 1915)

(57) Stuart MaCintyre, A Proletarian Science: Marxism in Britain 1917-1933 (1980) page 74

(58) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964) page 113