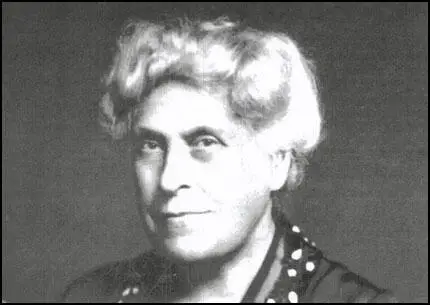

Margaret McMillan

Margaret McMillan, was born in Westchester County, New York, on the 20th July, 1860. Her parents, James and Jean McMillan, had originally come from Inverness but had emigrated to the United States in 1840. In 1865 James McMillan and his daughter Elizabeth died. Margaret also caught scarlet fever and although she survived it left her deaf (she recovered her hearing at fourteen).

Deeply upset by these events, Mrs. McMillan decided to take her two young daughters, Margaret and Rachel McMillan back to Scotland. Rachel and Margaret both attended the Inverness High School and were able to make good use of their grandparents well-stocked library. When Jean McMillan died in 1877 it was decided that Rachel would remain in Inverness to nurse her very sick grandmother, while Margaret was sent away to be trained as a governess.

In 1887 Rachel paid a visit to a cousin in Edinburgh. Her cousin took her to church where she heard an impressive sermon by John Glasse, a Christian Socialist. Rachel was also introduced to John Gilray, another recent convert to this religious group. Gilray gave Rachel copies of Justice, a socialist newspaper and Peter Kropotkin's Advice to the Young. Rachel was impressed by what she read. She particularly liked the articles by William Morris and William Stead.

During the following week Rachel McMillan went with Gilray to several socialist meetings in Edinburgh. When she arrived home in Inverness she wrote to a friend about her new beliefs: "I think that, very soon, when these teachings and ideas are better known, people generally will declare themselves Socialists."

Rachel's grandmother died in July 1888. Freed of her nursing responsibilities, Rachel McMillan joined Margaret in London and the two remained together for most of the rest of their lives. Margaret, who was employed as a junior superintendent in a home for young girls, found Rachel a similar job in Bloomsbury.

Rachel converted Margaret to socialism and together they attended political meetings where they met William Morris, H. M. Hyndman, Peter Kropotkin, William Stead and Ben Tillet. They also began contributing to the magazine Christian Socialist and gave free evening lessons to working class girls in London. Margaret later wrote: "I taught them singing, or rather I talked to them while they jeered at me." It was at this time that the two sisters became aware of the connection between the workers' physical environment and their intellectual development.

In October 1889, Rachel and Margaret helped the workers during the London Dock Strike. The continued to be involved in spreading the word of Christian Socialism to industrial workers and in 1892 it was suggested that their efforts would be appreciated in Bradford.

Although for the next few years they were based in Bradford, Rachel and Margaret toured the industrial regions speaking at meetings and visiting the homes of the poor. As well as attending Christian Socialist meetings, the sisters joined the Fabian Society, the Labour Church, the Social Democratic Federation and the newly formed Independent Labour Party (ILP).

Margaret and Rachel's work in Bradford convinced them that they should concentrate on trying to improve the physical and intellectual welfare of the slum child. In 1892 Margaret joined Dr. James Kerr, Bradford's school medical officer, to carry out the first medical inspection of elementary school children in Britain. Kerr and McMillan published a report on the medical problems that they found and began a campaign to improve the health of children by arguing that local authorities should install bathrooms, improve ventilation and supply free school meals.

The sisters remained active in politics and Margaret McMillan became the Independent Labour Party candidate for the Bradford School Board. Elected in 1894 and working closely with Fred Jowett, leader of the ILP on the local council, Margaret now began to influence what went on in Bradford schools. She also wrote several books and pamphlets on the subject including Child Labour and the Half Time System (1896) and Early Childhood (1900).

In 1902 Margaret joined Rachel McMillan in London. The sisters joined the recently formed Labour Party and worked closely with leaders of the movement including James Keir Hardie and George Lansbury. Margaret continued to write books on health and education. In 1904 she published her most important book, Education Through the Imagination (1904) and followed this with The Economic Aspects of Child Labour and Education (1905).

The two sisters joined with their old friend, Katharine Glasier, to lead the campaign for school meals and eventually the House of Commons became convinced that hungry children cannot learn and passed the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act. The legislation accepted the argument put forward by the McMillan sisters that if the state insists on compulsory education it must take responsibility for the proper nourishment of school children.

In 1908 Margaret and Rachel McMillan opened the country's first school clinic in Bow. This was followed by the Deptford Clinic in 1910 that served a number of schools in the area. The clinic provided dental help, surgical aid and lessons in breathing and posture. The sisters also established a Night Camp where slum children could wash and wear clean nightclothes. In 1911 Margaret McMillan published The Child and the State where she criticised the tendency of schools in working class areas to concentrate on preparing children for unskilled and monotonous jobs. Margaret argued that instead schools should be offering a broad and humane education.

Rachel and Margaret both supported the campaign for universal suffrage. They were against the use of violence and tended to favour the approach of the NUWSS. However, they disagreed with the way WSPU members were treated in prison and at one meeting where they were protesting against the Cat and Mouse Act, the sisters were physically assaulted by a group of policemen.

In 1914 the sisters decided to start an Open-Air Nursery School & Training Centre in Deptford. Within a few weeks there were thirty children at the school ranging in age from eighteen months to seven years. Rachel, who was mainly responsible for the kindergarten, proudly pointed out that in the first six months there was only one case of illness and, because of precautions that she took, this case of measles did not spread to the other children.

Rachel McMillan died on 25th March, 1917. Although devastated by the loss of her sister, Margaret continued the run the Peckham Nursery. She also served on the London County Council and wrote a series of influential books that included The Nursery School (1919) and Nursery Schools: A Practical Handbook (1920).

In her later years Margaret McMillan became interested in the subject of nursing. With the financial help of Lloyds of London, she established a new college to train nurses and teachers. Named after her beloved sister, the Rachel McMillan College was opened in Deptford on 8th May, 1930.

Margaret McMillan died on 29 March, 1931. Afterwards her friend Walter Cresswell wrote a memoir of the McMillan sisters: "Such persons, single-minded, pure in heart, blazing with selfless love, are the jewels of our species. There is more essential Christianity in them than in a multitude of bishops."

Primary Sources

(1) In 1927 Margaret McMillan later recalled her first experience of schooling in Inverness.

Our mother was possessed by one aim - to give us children a proper education. She spared nothing in the pursuit of this end. The first experience of school was a little disconcerting and in some ways even alarming. The children sat in large room with a desk that looked like a pulpit. This desk contained, as we afterwards learned with horror, a tawse, or leathern strap, with four tongues, which the masters used with energy, not indeed for the punishment of girls, but only of boys. In spite of our immunity, we were filled with anxiety and distress, and had a deep sympathy with the unruly boys.

There were other things that were disturbing. The schools of that day, even for well-to-do children whose parents paid high fees (our mother paid them with difficulty), had a low standard in respect of hygiene. Dusty walls, greasy slates, no hot water and no care of the physical body.

(2) In 1888 Rachel and Margaret McMillan began teaching working class children in London. Later Margaret wrote about how the children reacted to her.

At Whitechapel I held a class for factory girls. I taught them singing, or rather I talked to them while they jeered at me. We sat in a dim room with a sawdusty floor, which we reached by climbing up some rickety steps from a muddy court.

The girls led a dreadful life. All of them came to the class after a long day's work in the factory. They came, as I soon found, merely for a lark. They crowded in, some big and brawny, some small and pale and anemic. They took the penny books, did not tear them up at once, and even made a feint of paying attention, but this only to make sure of a better joke. They were terrible lessons. My hat was never on my own head, and my coat was often missing when I wanted it. Squirts of water reached me and worse things, everyone amused herself as she chose.

One evening there was a lull. The girls were sobered by some rumours of a new reduction in wages. Rose, a ringleader, a big stout rope girl, with a thick fringe and swinging brass ear-rings, sat on the platform, red arms akimbo, and red face grave.

"What do you come down here for anyway? she said. "What's your game? You're losing your chances, you know, coming down here. Ain't you got a chap? You ain't bad looking, you know. You're hair done comical and that! and no ear-rings, nor nothing, but you ain't bad-looking. I say chuck it," said Rose earnestly. "These lessons of yours ain't no good to us. What do you take us for? Kids? We ain't going to learn no more. Get a chap for yourself, my girl: that's what you got to do.

(3) In a book published in 1927, Margaret McMillan wrote about the different socialist leaders she met in her youth. This included H. H. Hyndman and William Morris.

H. M. Hyndman, the great apostle of Karl Marx, was a rather corpulent, long-bearded man of fifty-five. He had an astonishing gift of oratory and was at once provocative and convincing. He spoke with the vehemence of a great soul and the simplicity of a child. Above all, he had vision. He saw the new society. His party, the Social Democratic Federation stood for Adult Suffrage. It worked for the Nationalization of Land and the instruments of production. These were to be administered for the good of all the people, not for the profiteering or benefit of a small class.

We were invited to meet William Morris at Kelmscott House. Mr. Morris received us with patient cordiality. Dressed in navy blue, and with his hair much ruffled, he looked like a sea captain receiving guests on a stormy day, but glad to see them. He wanted to hear about his Edinburgh friends, especially John Glasse, with whom he could discuss handloom weaving as well as literature or Socialism. He lighted his pipe and talked, sitting upright in a high chair. We listened to his copious, glittering talk. Morris belonged to a rich, radiant, present world. He created it. He was practical as well as impatient.

(4) In 1892, F. W. Jowlett of the Social Democratic Federation, asked Rachel and Margaret McMillan to move to Bradford. Rachel wrote about her experiences in her book, The Life of Rachel McMillan that was published in 1927.

We arrived on a stormy night in November. Coming out from the entrance of the Midland station, we saw, in a swuther of rain, the shining statue of Richard Oastler standing in the Market Square, with two black and bowed little mill-workers standing at his knee.

Next morning we awoke in a new and quite unknown world. It was a Sunday, and the smoke cloud that usually enveloped the city had lifted. Tall dark chimneys reaching skywards like monstrous trees, made dark outlines against the faint grey of the sunny morning. On weekdays these big stone monsters belched forth smoke as black as pitch that fell in choking clouds.

The condition of the poorer children was worse than anything that was described or painted. It was a thing that this generation is glad to forget. The neglect of infants, the utter neglect almost of toddlers and older children, the blight of early labour, all combined to make of a once vigorous people a race of undergrown and spoiled adolescents; and just as people looked on at the torture two hundred years ago and less, without any great indignation, so in the 1890s people saw the misery of poor children without perturbation.

(5) Fenner Brockway, a member of the Independent Labour Party, later recalled the contribution that Margaret McMillan and Fred Jowett made to the social reforms in Bradford.

Margaret McMillan is a figure closely associated with Bradford's pioneering contribution to child welfare and education, with whom Fred Jowett worked closely and revered. Her coming to Bradford was characteristic. Accompanied by her sister Rachel, she travelled from London to lecture at the Labour Church in 1893, and they found themselves among men and women whom they recognised at once as their natural comrades.

Margaret McMillan remained in Bradford, devoting her whole time to the ILP, addressing meetings tirelessly in schoolrooms and at street corners, travelling all over the North to spread the socialist gospel. A year after coming to Bradford Margaret was elected to the School Board and began the educational work for which she is famed. Among other things, school baths and medical treatment were introduced, a physical care unknown in schools at that time, and for which, indeed no legal provision existed.

(6) Margaret Bondfield, A Life's Work (1948)

During my work in the district I met large numbers of the comrades who told me stories of the transformation in the borough council's attitude to the child health problem as a result of the work of Margaret Macmillan, who came to live in Bradford in 1893. From 1893 to 1902 Margaret had led the fight for the communal spirit in the town, where the Cinderella Club was started by the Socialist paper The Clarion, edited by Robert Blatchford. The Cinderella Club initiated the feeding of school-children in 1894, and in that year Margaret was elected to the Bradford School Board.

(7) In 1913 Rachel and Margaret McMillan attended a meeting called to protest against the Cat and Mouse Act.

When the Cat and Mouse Bill came into operation we joined a committee formed by Sir Victor Horsley, and went with many other women in the House of Commons, with a protest signed by a great number of people. It was a beautiful day in August when we set off, all full of zeal, across the paved lawns about St. Margaret's, till we reached the House and mounted the steps leading to the foyer in front of the ante-room, whose swinging doors were closed to us. There we stood a long time. An old lady was on the step above us - she was dressed very daintily in amethyst silk, her hair swathed in lace, among whose fold gleamed a thin gold chain. I was looking admiringly at her when suddenly a force of policemen swung down on us like a Highland regiment. We were tossed like dust down the steps. A moment later I was on the floor, the crowd behind flung over me in their wild descent. There was a big meeting that night at which I was to speak, but, of course, I did not speak at that meeting, nor at any other - for weeks.

(8) On 26th August 1916, Rachel and Margaret McMillan's house in London was bombedby a Zeppelin.

Looking out from my bedroom window, we saw something bright and sparkling in the sky.

"What can it be? I said to Rachel.

She looked at it steadily. "A Zeppelin"

Two or three of our friends ran upstairs to warn us. "It's a Zeppelin dropping bombs, or going to." We all gazed at it if fascinated.

A terrific blast struck the house as we went downstairs. I looked up and saw that Rachel had not followed us. In the same moment, an awful explosion shook the little house to its foundations. I called, and she appeared on the last landing carrying blankets. She had just time to join us when a third crash sent all our windows in, and the ironwork along the outer wall, which served as a ventilator for the lower room.