George Sims

George Sims began work at the age of eight as a page in a Park Lane mansion. It is claimed that he "whetted his intellectual curiosity" by reading The Times. (1)

Sims became a carpenter and a member of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). With the help of Alfred Salter, a doctor working in Bermondsey, he won a place at Ruskin College. (2)

Dennis Hird was the principal of the college. Hird was a member of the SDF and the former rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor, who had been sacked for a lecture he gave on the subject, Jesus the Socialist (it was later published as a pamphlet that sold 70,000 copies). (3)

Hird taught sociology, evolution and formal logic. This meant that Hird was teaching sociology to his students, nearly 50 years before it was officially recognised by the University of Oxford. During these sessions he introduced his students to the work of Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and Émile Durkheim.

The teaching of Hird had a dramatic impact on George Sims: "I had tried for years to get a feeling of reality in religion, to feel that God and the Christ were of me and with me, the reality never came... But with the first reading of the Communist Manifesto, how the pamphlet appealed to something in me, some revolt against things as they are... We are neither fatalists, nor believers in miracles - simply people who know... the inevitability of social evolution, of development and progress based upon material needs as a stepping-stone to our higher selves." (4)

1909 Student Strike

In 1909 Lord George Curzon published Principles and Methods of University Reform. In the book he pointed out that it was vitally important to control the education of future leaders of the labour movement. He urged universities to promote the growth of an elite leadership and rejected the 19th century educational reformers call for reform on utilitarian lines to encourage "upward movement" of the capitalist middle class: "We must strive to attract the best, for they will be the leaders of the upward movement... and it is of great importance that their early training should be conducted on liberal rather than on utilitarian lines." (5)

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life. (6)

It is believed that 20 students, including George Sims, were members of the radical Plebs League. Sims helped to organise a students' strike in support of Hird. (7) The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. However, the students decided that they would use the Plebs League and its journal, the Plebs' Magazine, to campaign for the setting up of a new and real Labour College. (8)

Dennis Hird received very little support from other advocates of working-class education. Albert Mansbridge, the

founder of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) in 1903, blamed Hird's preaching of socialism for his dismissal. In a letter to a French friend, he wrote "the low-down practice of Dennis Hird in playing upon the class consciousness of swollen-headed students embittered by the gorgeous panorama ever before them of an Oxford in which they have no part." (9)

Central Labour College

Noah Ablett took the lead in establishing an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. George Sims, who had been expelled after his involvement in the Ruskin strike, played an important role in raising the funds for the project. On 2nd August, 1909, Ablett and Sims organised a conference that was attended by 200 trade union representatives. Dennis Hird, Walter Vrooman and Frank Lester Ward were all at the conference. (10)

Sims explained that the "last link which bound Ruskin College to the Labour Movement had been broken, the majority of the students had taken the bold step of trying to found a new college owned and controlled by the organised Labour Movement." (11) Ablett moved the resolution: "That this Conference of workers declares that the time has now arrived when the working class should enter the educational world to work out its own problems for itself." (12)

The conference agreed to establish the Central Labour College (CLC). The students rented two houses in Bradmore Road in Oxford. It was decided that "two-thirds of representation on Board of Management shall be Labour organisations on the same lines as the Labour Party constitution, namely, Trade Unions, Socialist societies and Co-operative societies." Most of the original funding came from the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). (13)

Dennis Hird agreed to act as Principal and to lecture on sociology and other subjects, without any salary. George Sims worked as its secretary and Alfred Hacking was employed as tutor in English grammar and literature. Fred Charles accepted a post as tutor in industrial and political history. The teaching staff was supplemented by regular visiting lecturers, such as Frank Horrabin, Winifred Batho, Rebecca West, Emily Wilding Davison, H. N. Brailsford, Arthur Horner and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence.

The Plebs Magazine pointed out the main objectives of the Central Labour College: "The education given at the Central Labour College to the selected working men of the Labour Movement is to serve essentially as a means for the education of the workers throughout the country. Arrangements are being made in this direction, and we hope to be able to announce at no distant date the inauguration of a systematic provincial scheme of working-class education. The training of men for the purpose of going out into the industrial world to train their fellow-workers concerning those questions which so vitally affect their everyday life, is a work, we feel certain, that will in a short time give to the Labour Movement the intelligent discipline and solidarity it so much needs. (14)

William Craik originally was a student at the college. However, in 1910, Hird appointed him as Vice-Principal. In 1911 the college moved to London. "Very soon after the College arrived in Kensington it began to conduct evening classes, both within and without, for the working men and women in the district, and to extend their range. Not many years were to pass before there was hardly a suburb in Greater London without one or more Labour College classes at work in it. Nothing like this, needless to say, would have been possible had the College remained in Oxford." (15)

John Saville has argued that the Central Labour College provided the kind of socialist education that was not provided by Ruskin College and the Workers' Educational Association. "What we have in these years is both the attempt to channel working-class education into the safe and liberal outlets of the Workers' Educational Association and Ruskin College, and the development of working-class initiatives from below; and it is the latter only which made its contribution to the socialist movement - and a considerable contribution it was." (16)

Bernard Jennings agrees with Saville on this point and points out that Richard Tawney, A. D. Lindsay and Archbishop William Temple were all supporters of Ruskin College and the WEA over the Central Labour College: "There is no doubt that the establishment preferred the WEA and Ruskin to the Labour college movement, a fact exploited quite brazenly by the WEA in the 1920s. Temple, Tawney and A. D. Lindsay all warned the Board of Education and the LEAs that unless they supported the WEA and respected its academic freedom, workers' education would fall to the CLC." (17)

The Central Labour College was always short of money. The Plebs Magazine was used to raise funds. "Your cash will be used to good purpose - make no doubt of that. The CLC flag has been kept flying up to now by the pluck, devotion and enthusiasm of the garrison. Only those, perhaps, who - like the present writer - have had an occasional glimpse behind the scenes, know the extent of the devotion and that enthusiasm. What are you going to do about it?" (18)

George Sims: 1914-1943

Dennis Hird suffered for many years with thrombosis. He became very ill in 1913 and was confined to his bed for over a year. He returned to work in 1914 but in May 1915 he was forced back to his bed. George Sims and William Craik took over most of his details. However, Sims and Craik were conscripted into the British Army in 1917 and it was forced to close until the end of the First World War. (19)

George Sims, a sergeant-major in a motor machine-gun unit serving on the Italian Front, was not demoblised until the summer of 1919. His great friend, Frank Horrabin, was not so lucky and he was severely wounded in the last Allied offensive of the war.

William Craik visited Hird in 1919 and "despite the tediousness of his prolonged confinement in bed, he was cheerful and quite hopeful of being able to return to his post." Unfortunately he did not recover and died on 13th July 1920. Craik now replaced him as Principal of the Central Labour College. (20)

George Sims taught economics at the Central Labour College. According to Stuart MaCintyre: "In their first year students studied economics, industrial history, the history of socialism, sociology, English and logic or the Science of Understanding. In the second year economics and philosophy were studied at a more advanced level, along with extra classes chosen from such subjects (offered by guest lecturers) as imperialism, economic geography, trade union law, literature, psychology, languages, etc." (21)

The Central Labour College educated several future trade union leaders and Labour Party MPs. This included Arthur J. Cook, Frank Hodges, William H. Mainwaring, Ellen Wilkinson, Lewis Jones, Ness Edwards, Idris Cox, Hubert Beaumont, William Coldrick, Jim Griffiths, Harold Heslop, Morgan Phillips, Joseph Sparks, Ivor Thomas, Edward Williams, Arthur Jenkins, Will Owen, William Paling, George Dagger and James Harrison.

Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) attempted to gain control of the Plebs League and the Central Labour College as it believed that "working class education can only achieve its object under the leadership of the Party", however, Craik insisted that "such education can best be provided by a specifically educational organisation, supported by all workers' industrial and political organisations and uncommitted to any sectional policy". (22)

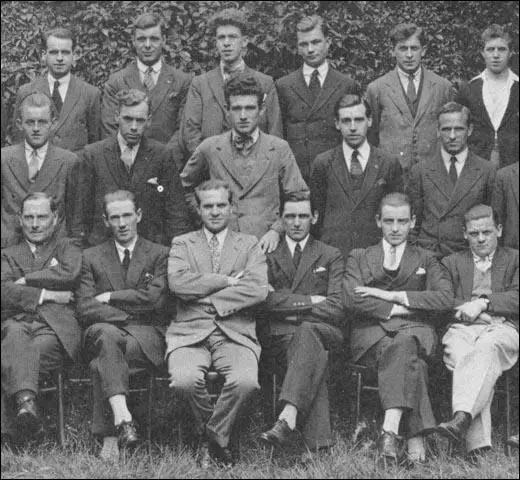

first left on the bottom row. William Craik is in the middle of that row.

The conservative press became concerned about how the Central Labour College taught economics. The Spectator complained that Working Men's Colleges such as the CLC were dangerous places: "The Colleges are not institutions for learning and research as such; they exist rather for the propagation of particular views. They teach Collectivism, and they turn out their pupils fully equipped apostles of that doctrine. They are seminaries rather than colleges.... The obvious source of instruction for the manual worker to turn to is the economic teaching approved of by the Trade Unions. Practically all this teaching comes from Socialists; ranging from State Socialists through Guild Socialists and Syndicalists to Marxians." (23)

In 1921 the Trade Union Congress established the National Council of Labour Colleges (NCLC) as a co-ordinating body for the movement of labour colleges. George Sims, who had been the main fund raiser for the Central Labour College, welcomed the move. He was unhappy that the National Union of Railwaymen and the National Union of Mineworkers had taken over the complete control of the CLC and feared that they might undermine academic freedom of the organisation. Sims therefore accepted the post of secretary of the NCLC. (24)

George Sims died in 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) George Sims, letter to Winifred Batho (1918)

I had tried for years to get a feeling of reality in religion, to feel that God and the Christ were of me and with me, the reality never came... But with the first reading of the Communist Manifesto, how the pamphlet appealed to something in me, some revolt against things as they are... We are neither fatalists, nor believers in miracles - simply people who know... the inevitability of social evolution, of development and progress based upon material needs as a stepping-stone to our higher selves.

(2) Stuart MaCintyre, A Proletarian Science: Marxism in Britain 1917-1933 (1980)

It would be impossible to exhaust the variety of starting points: witness George Sims, afterwards a carpenter and the original secretary of the Central Labour College, who began work at the age of eight and whetted his intellectual curiosity by reading The Times to the master of the Park Lane mansion in which he was a page. Irrespective of initial impulse, these individual intellectual odysseys were likely to share certain common features. Religion was usually important, if only because the Bible was one book which most had read, but more particularly because the question of religious belief preoccupied the late Victorians and a great many autodidacts came to base their education on the secular press and literature.

(3) William Craik, Central Labour College (1964)

Coming to the College in January, 1908, to take up a two-year course of study there, George Sims brought with him a number of years of experience of active work in the trade union and socialist movement, mostly in Bermondsey. He attracted the attention of a well-known personality in that borough, Dr. Salter, a prominent figure on the London County Council and an active member of the Independent Labour Party. Although George Sims was a member of the Social Democratic Party, Dr. Salter was sufficiently interested in this local socialist carpenter to make him the generous offer of a two-year scholarship at Ruskin College, which Sims accepted.

During his residence at Ruskin, Sims took a prominent part in the internal work and life of the students there. He had acquired enough knowledge of the theoretical works of Karl Marx to enable him to do a great deal to compensate for the almost complete ignorance of Marx's work shown by the Ruskin lecturer on political economy, by helping in the conduct of the classes run by the students themselves for the study of this very basic subject. He soon became associated with those earlier students who were already expressing their increasing dissatisfaction with much of the education they were receiving at Ruskin, and with the resultant movement of unconcealed dissent at the efforts being made to bring the teaching there in educational accord with that of the University. When the Plebs League was set in motion to arrest this development, Sims became one of its most active leaders. As such, he was already marked down by Lees Smith and his friends for removal, just as Dennis Hird had been for his suspected authorship of the League, although actually that organisation was already an accomplished fact before Dennis Hird ever knew of it.

It only needed Sims's role in the recent strike to seal his fate as far as further residence as a Ruskin student was concerned. The method of his disposal differed from that of Hird's going. Only after his back was turned and he was already on the enforced vacation, did the Secretary of the College, Bertram Wilson, on orders no doubt from his boss, write to Dr. Salter and induce him to discontinue his scholarship to George Sims. What Salter was told in this letter was, naturally, never disclosed. In any case it was the end of Sims as a student at Ruskin College. It marked, however, the beginning of years of active and very valuable service by him in the campaign that now immediately opened for the creation of the new Central Labour College, and in the subsequent development of that institution.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)