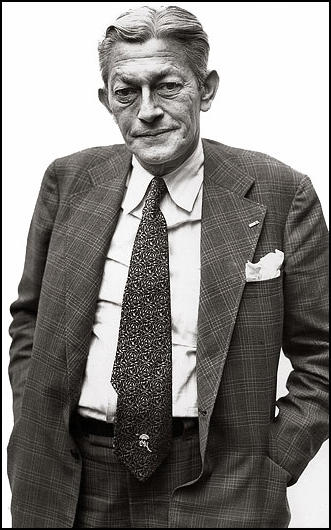

James Jesus Angleton

James Jesus Angleton was born in Boise, Idaho, on 9th December, 1917. His father, Hugh Angleton, was a former cavalry officer who met his wife, a seventeen-year-old Mexican woman, Carmen Mercedes Moreno, while serving in Mexico, under General John J. Pershing. (1)

Hugh Angleton was an executive of the National Cash Register Company. (2) Thomas McCoy, a family friend, described him as "a six-foot-four, raw-boned, red-faced farm boy; a broad super-friendly guy, who was the outgoing salesman type and a born trader. He and his son were as different as one can imagine." (3)

Carmen Mercedes Moreno was a devout Catholic who insisted on giving him the name of Jesus. "As he grew older he became proud of his Mexican background - but, at the beginning, no. He never liked to use his middle name... Who likes to go around with a middle name of Jesus?" (4)

In 1931 Hugh Angleton moved his family to Milan, for business reasons. He was very impressed with Benito Mussolini and his friend, Max Corvo, commented "Hugh Angleton... was ultra-conservative, a sympathizer with Fascist officials. He was certainly not unfriendly with the Fascists." (5) In 1933 Angleton was sent to Malvern College. (6) "He learned all about snobbery, prejudice, and school beatings. Before he left three years later he had served as a prefect, a corporal in the Officers' Training Corps, and joined the Old Malvern Society. He seems to have become more English than the English, a useful ruse perhaps for Malvern's lone half-Mexican Yank." (7) Angleton later recalled: "I was brought up in England in one of my formative years and I must confess that I learned, at least I was disciplined to learn, certain features of life, and what I regarded as duty." (8)

James Jesus Angleton entered Yale University in 1937: "Angleton had already developed a distinctive personal style. He spoke with a slight English accent (probably not an affection after three years in the country), and was tall, athletic, bright, and handsome... By conventional standards he was a poor student, frequently missing class, excelling only in those subjects that interested him, and occasionally failing those that didn't." (9) A fellow student, Reed Whittemore, later commented: "All through Yale, Jim was backward at completing school papers... It may be that he was just lazy - or maybe he had a psychological problem. He had the class record for incompletes, but he could invariably whitewash over these missing grades because he had a favorable presence with the teachers, who for the most part liked him a lot." (10)

Angleton and Whittemore edited a quarterly of original poetry, called Furioso, financed mostly by subscriptions raised by Whittemore's aunt. Angleton and Whittemore were both promising poets and other contributors included Archibald MacLeish, Ezra Pound, E.E. Cummings and William Carlos Williams. Whittemore later commented: "When we were short of money, which was most of the tune, we paid off our poets with fine Italian cravats from the stock that the Angleton haberdasher in Italy kept replenishing." (11)

In the autumn of 1941 Angleton moved on to Harvard Law School. Soon afterwards he met Cicely Harriet d’Autremont: "There was nothing in the room except a large reproduction of El Greco's View of Toledo. It showed a huge unearthly green sky. Jim was standing underneath the picture. If anything went together, it was him and the picture. I fell madly in love at first sight. I'd never met anyone like him in my life. He was so charismatic. It was as if the lightning in the picture had suddenly struck me. He had an El Greco face. It was extraordinary." (12) They became engaged in April 1943, a few weeks after Angleton had been drafted into the United States Army. Hugh Angleton, disapproved of the relationship but the wedding took place quietly three months later on 17th July, in Battle Creek, Michigan. (13)

James Hugh Angleton became a senior figure in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and was on the staff of Colonel William Donovan. It had been created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The OSS replaced the former American intelligence system, Office of the Coordinator of Information (OCI) that was considered to be ineffective. The OSS had responsibility for collecting and analyzing information about countries at war with the United States. It also helped to organize guerrilla fighting, sabotage and espionage.

In August 1944, Lieutenant Colonel James Hugh Angleton and Norman Holmes Pearson, Angleton's former English professor at Yale University, contacted James R. Murphy, the head of the new X-2 CI (Counter Intelligence) branch of the OSS. On 25th September, 1943, Murphy issued a memo: "I would greatly appreciate it if you could get provisional security for Corporal James Angleton in order that he may commence OSS school on Monday. His father is with this branch... In addition young Angleton is very well known to Norman Pearson, who recommended him to me." (14)

During his training James Jesus Angleton met Richard Helms, the former national advertising manager of the Indianapolis Times, who had joined the OSS in August 1943. In his autobiography, A Look Over My Shoulder (2003) he commented: "As a young man, Jim was bone thin, gaunt, and aggressively intellectual in aspect. His not entirely coincidental resemblance to T. S. Eliot was intensified by a European wardrobe, studious manner, heavy glasses, and lifelong interest in poetry." (15)

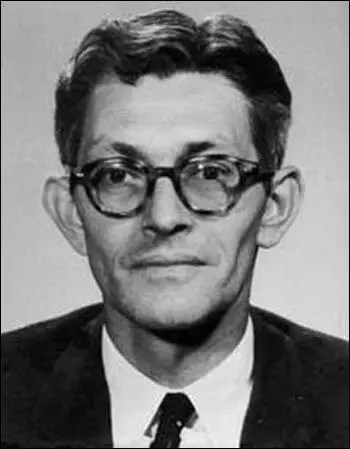

James Jesus Angleton in London

On 28th December, 1943, James Jesus Angleton, arrived in London to work for the Italian section of X-2 C.I. Soon after arriving in England he met Kim Philby, who was head of MI6's Iberian section. It was the start of a long friendship: "Once I met Philby, the world of intelligence that had once interested me consumed me. He had taken on the Nazis and Fascists head-on and penetrated their operations in Spain and Germany. His sophistication and experience appealed to us... Kim taught me a great deal." (16) Phillip Knightley, the author of Philby: KGB Masterspy (1988), has pointed out: "Philby was one of Angleton's instructors, his prime tutor in counter-intelligence; Angleton came to look upon him as an elder-brother figure." (17)

Angleton impressed his senior officers and within six months he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and was appointed as chief of the Italian Desk for the European Theater of Operations. A colleague, John Raymond Baine, later remembered him as a well-respected officer: "His voice and manner were always on the quiet side. He never laughed loudly or acted in a boisterous way. Both his talk and his laughter were always soft. He was captivating, and had the ability to dominate a conversation without ever lifting his voice." (18)

OSS Officer in Rome

In October 1944 Angleton was transferred to Rome as commanding officer of Special Counter-Intelligence Unit Z. In March 1945, he was promoted to first lieutenant and became head of X-2 for the whole of Italy. At the age of twenty-seven, he was the youngest X-2 Branch chief in all of OSS. According to Charles J.V. Murphy: "His (Angleton) unit uncovered some of the secret correspondence between Hitler and Mussolini that was later introduced into the Nuremberg trials as proof of their conspiracy." (19) Raymond Rocca was his senior staff officer. The two men were to remain close friends for the next thirty years. (20)

After the war Angleton and Rocca remained in Italy. They worked closely "with Italian counterintelligence to uncover reams of data about Soviet operations". (21) Angleton's biographer, Tom Mangold, has pointed out: "As Italian fascism collapsed and the German retreat quickened, Angleton found himself targeting subtle new enemies, including lingering Fascists and, more importantly for him, nascent Communist networks. The young Counterintelligence chief was now in his element: recently declassified documents show Angleton at the zenith of his wartime career... His unit's top secret intelligence sources... burgled their way across the open city with seeming impunity." (22)

Cicely Angleton gave birth to a son, James Charles, in August, 1944. James Jesus Angleton did not return to the United States until November 1945. Tom Mangold has claimed that: "It had now been nearly two years since he left for Europe. The long-awaited reunion, during a two-day stopover in New York, was a total disaster. The couple had become casualties of the protracted separation." (23)

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

Cicely claimed: "We just didn't know each other anymore. Jim was wishing we were not married, but he was too nice to say it. He thought the situation was hopeless. He was all caught up in his career. We had both changed. He was typical of a war marriage. It was exactly what his father had warned us about in 1943... Jim no longer cared about our relationship, he just wanted to get back to Italy - back to the life he knew and loved. He didn't want a family. The marriage seemed to be annihilated then and there." (24) Cicely moved back to Tucson to live with her family. A few months later initiated divorce proceedings against her husband on grounds of desertion. However, Angleton did not want a divorce and he refused to sign the necessary documents.

Angleton now returned to Italy. It is claimed that William Donovan, the head of the Office of Strategic Services asked Angleton to "help the provisional Italian government beat off a threatened Communist takeover". Angleton discovered documents to show that communist parties in Europe were following instructions from the Soviet Union. Angleton was also able to forecast the break-up of the relationship between Joseph Stalin and Josip Tito. "He (James Jesus Angleton) and his principal associate for all of his career, Raymond Rocca... ferreted out the exchange of correspondence between Stalin and Tito that foreshadowed the 1948 breach between them." (25)

Central Intelligence Agency

In December 1947 Angleton returned to the United States. He met up with his wife, Cicely Angleton, and they agreed to make another effort to save their marriage. "He had calmed down a little, we got back together, we rediscovered each other. But he was a nervous wreck, nervous about family responsibilities, and his health had suffered badly. He was eager to make a go of it and I needed to be with him." (26) They lived in Tucson until they moved to Washington in June 1948 to begin his career with the recently established Central Intelligence Agency.

Angleton's first post was as a senior advisor to Frank Wisner, the director of the Office of Special Operations (OSO). The OSO had responsibility for espionage and counter-espionage. (27) Wisner was told to create an organization that concentrated on "propaganda, economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world". Angleton's job was to oversee special studies involving all countries where the CIA was operating. He later explained that his experiences in Europe meant that he was "sharply aware of the Soviet long-term objectives in subversion." (28)

In January 1949 James Jesus Angleton had to travel to Europe on CIA business. He obviously believed that the mission was dangerous as he made out a three-page "Last Will and Testament". His biographer, Tom Mangold, has argued that it provides "a rare insight into the private man". (29) Angleton left most of his "real and personal property" to his wife. He bequeathed his precious fishing tackle to his young son, James Charles Angleton, "in order that he might have some small inclination to follow this sport - whether it will in fact be a satisfaction to him is material since no two humans need to seek the same retreat." Angleton also left small mementos to Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, Raymond Rocca and Norman Holmes Pearson. (30)

Georgetown

James and Cicely Angleton associated with a group of people who lived in Georgetown. They were mainly journalists, CIA officers and government officials. This included Mary Pinchot Meyer, Cord Meyer, Anne Truitt, James Truitt, Frank Wisner, Thomas Braden, Richard Bissell, Desmond FitzGerald, Wistar Janney, Joseph Alsop, Tracy Barnes, Philip Graham, Katharine Graham, David Bruce, Ben Bradlee, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen and Paul Nitze.

Nina Burleigh, the author of A Very Private Woman (1998) has pointed out: "The younger families - the Meyers, Janneys, Truitts, Pittmans, Lanahans, and Angletons - spent a great deal of leisure time together. There were evening get-togethers, and sometimes the families took weekend camping trips to nearby beaches or mountains when husbands could get away... On Saturday mornings in the fall, the adults got together and played touch football in a park north of Georgetown while their children biked around the sidelines, then all retired to someone's house for lunch and drinks... The Janneys had a pool, and on hot summer nights the parties were aloud, drunken affairs, filled with laughter, dancing, and the sound of breaking glass and people being pushed into the pool." (31) Ben Bradlee recalls in his autobiography, The Good Life (1995) that he was also part of the same group. "Socially our crowd consisted of young couples, around thirty years old, with young kids, being raised without help by their mothers, and without many financial resources." (32)

Kim Philby

In 1949 Angleton's old friend, Kim Philby, became MI6's representative in Washington, as the top British Secret Service officer working in liaison with the CIA and FBI. He also handled secret communications between the British prime minister, Clement Attlee and President Harry S. Truman. According to Ray Cline, it had been left to the Americans to select their preferred candidate and it was James Jesus Angleton who was the main person advocating appointing Philby. (33) Philby wrote in My Secret War (1968): "At one stroke, it would take me right back into the middle of intelligence policy making and it would give me a close-up view of the American intelligence organisations." (34)

Philby's home in Nebraska Avenue became a gathering place for Washington's intelligence elite. This included James Jesus Angleton, Walter Bedell Smith (Director of the CIA), Allen Dulles (Deputy Director of the CIA), Frank Wisner (head of the Office of Policy Coordination), William K. Harvey (CIA counter-intelligence) and Robert Lamphere (FBI Soviet Section). Philby made a point of dropping in on the offices of American intelligence officers in the late afternoon, knowing that his hosts would sooner or later "suggest drifting out to a friendly bar for a further round of shop talk." (35) As one CIA officer pointed out: "Intelligence officers talk trade among themselves all the time... Philby was privy to a hell of a lot beyond what he should have known." (36)

Philby was especially close to Angleton. Philby later explained they had lunch at Harvey's Restaurant every week: "We formed the habit of lunching once a week at Harvey's where he demonstrated regularly that overwork was not his only vice. He was one of the thinnest men I have ever met, and one of the biggest eaters. Lucky Jim! After a year of keeping up with Angleton, I took the advice of an elderly lady friend and went on a diet, dropping from thirteen stone to about eleven in three months. Our close association was, I am sure, inspired by genuine friendliness on both sides. But we both had ulterior motives. Angleton wanted to place the burden of exchanges between CIA and SIS on the CIA office in London - which was about ten times as big as mine. By doing so, he could exert the maximum pressure on SIS's headquarters while minimizing SIS intrusions into his own. As an exercise in nationalism, that was fair enough. By cultivating me to the full, he could better keep me under wraps. For my part, I was more than content to string him along. The greater the trust between us overtly, the less he would suspect covert action. Who gained most from this complex game I cannot say. But I had one big advantage. I knew what he was doing for CIA and he knew what I was doing for SIS. But the real nature of my interest was something he did not know. (37)

Burgess & Maclean

In 1950 Guy Burgess was appointed the first secretary at the British embassy in Washington. Kim Philby suggested to Aileen Philby that Burgess should live in the basement of their house. Nicholas Elliott explained that Aileen was completely opposed to the idea. "Knowing the trouble that would inevitably ensue - and remembering Burgess's drunken and homosexual orgies when he had stayed with them in Instanbul - Aileen resisted this move, but bowed in the end (and as usual) to Philby's wishes... The inevitable drunken scenes and disorder ensued and tested the marriage to its limits." (38)

Meredith Gardner and his code-breaking team at Arlington Hall discovered that a Soviet spy with the codename of Homer was found on a number of messages from the KGB station at the Soviet consulate-general in New York City to Moscow Centre. The cryptanalysts discovered that the spy had been in Washington since 1944. The FBI concluded that it could be one of 6,000 people. At first they concentrated their efforts on non-diplomatic employees of the embassy. In April 1951, the Venona decoders found the vital clue in one of the messages. Homer had had regular contacts with his Soviet control in New York, using his pregnant wife as an excuse. This information enabled them to identify the spy as Donald Maclean, the first secretary at the Washington embassy during the Second World War. (39)

Kim Philby was told of the breakthrough. Philby took the news calmly as there was no real evidence, as yet, to connect him directly with Maclean, and the two men had not met for several years. MI5 decided not to arrest Maclean straight away. The Venona material was too secret to be used in court and so it was decided to keep Maclean under surveillance in the hope of gathering further evidence, for example, catching him in direct contact with his Soviet controller. Philby relayed the news to Moscow and demanded that Maclean be extracted from the UK before he was interrogated and compromised the entire British spy network.

Philby made the decision to use Guy Burgess to warn Maclean that he must flee to Moscow. The two men dined in a Chinese restaurant in downtown Washington, selected because it had individual booths with piped music, to prevent any eavesdroppers. Burgess said he would return to London in order to receive details of the escape plan. Before he left Philby made Burgess promise he would not flee with Maclean to Moscow: "Don't go with him when he goes. If you do, that'll be the end of me. Swear that you won't." Philby was aware that if Burgess went with Maclean, he would be suspected as a member of the network. (40)

Burgess arrived back in England on 7th May 1951, and immediately contacted Anthony Blunt, who got a message to Yuri Modin, the Soviet controller of the Philby network. Blunt told Modin: "There's serious trouble, Guy Burgess has just arrived back in London. Homer's about to be arrested... It's only a question of days now, maybe hours... Donald's now in such a state that I'm convinced he'll break down the moment they arrest him." (41)

After receiving instructions from his superiors, Modin arranged for Maclean to escape to the Soviet Union. Modin was informed that Maclean would be arrested on 28th May. The plan was for Maclean to be interviewed by the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison. "It has been assumed that Morrison held a meeting and that someone present at that meeting tipped off Burgess." (42) Another possibility is that a senior figure in MI5 was a Soviet spy, and he told Modin of the plan to arrest Maclean. This is the view of Peter Wright who suspects it was Roger Hollis who provided Modin with the information. (43)

On 25th May 1951, Burgess appeared at the Maclean's home in Tatsfield with a rented car, packed bags and two round-trip tickets booked in false names for the Falaise, a pleasure boat leaving that night for St Malo in France. Modin had insisted that Burgess must accompany Maclean. He later explained: "The Centre had concluded that we had not one, but two burnt-out agents on our hands on our hands. Burgess had lost most of his former value to us... Even if he retained his job, he could never again feed intelligence to the KGB as he had done before. He was finished." (44)

Maclean and Burgess took a train to Paris, and then another train to Berne in Switzerland. They then picked up fake passports in false names from the Soviet embassy. They then took another train to Zurich, where they boarded a plan bound for Stockholm, with a stop-over in Prague. They left the airport and now safely behind the Iron Curtain, they were taken by car to Moscow. (45) On his arrival in the Soviet Union Maclean issued a statement: "I am haunted and burdened by what I know of official secrets, especially by the content of high-level Anglo-American conversations. The British Government, whom I have served, have betrayed the realm to Americans ... I wish to enable my beloved country to escape from the snare which faithless politicians have set ... I have decided that I can discharge my duty to my country only through prompt disclosure of this material to Stalin." (46)

When Donald Maclean defected in 1951 Philby became the chief suspect as the man who had tipped him off that he was being investigated. The main evidence against him was his friendship with Guy Burgess, who had gone with Maclean to Moscow. Philby was recalled to London. CIA chief, Walter Bedell Smith ordered any officers with knowledge of Philby and Burgess to submit reports on the men. William K. Harvey replied that after studying all the evidence he was convinced that "Philby was a Soviet spy". (47)

James Jesus Angleton reacted in a completely different way. In Angleton's estimation, Philby was no traitor, but an honest and brilliant man who had been cruelly duped by Burgess. According to Tom Mangold, "Angleton... remained convinced that his British friend would be cleared of suspicion" and warned Bedell Smith that if the CIA started making unsubstantiated charges of treachery against a senior MI6 officer this would seriously damage Anglo-American relations, since Philby was "held in high esteem" in London. (48)

Chief of Counter-Intelligence Staff

In early 1951 James Jesus Angleton was appointed head of the CIA's newly created Special Operations Group. In this post Angleton served as the CIA's exclusive liaison with Israeli intelligence. "One might have expected his unit to be part of the agency's Middle East Division. But it stayed under Angleton's tight, zealous command for the next twenty years - to the utter fury of the division's separate Arab desks. Angleton's ties with the Israelis gave him considerable prestige within the CIA and later added significantly to his expanding counter-intelligence empire." (49)

Allen Dulles, the new director of the CIA, commissioned Lieutenant General James Doolittle to report on the organization's CIA 's covert intelligence-collecting capabilities. Doolittle concluded that the CIA was losing the spy wars with the KGB. Doolittle advised "the intensification of the CIA's counter-intelligence efforts to prevent or detect and eliminate penetrations of CIA". (50) In December, 1954, Dulles' response to the report was to appoint Angleton to become first chief of the CIA's newly created Counter-Intelligence Staff.

Another CIA senior officer, Tom Braden, recalls that Angleton often reported privately to Dulles: "Jim came in and out of Dulles's office a lot. He always came alone and had this aura of secrecy about him, something that made him stand out-even among other secretive CIA officers. In those days, there was a general CIA camaraderie, but Jim made himself exempt from this. He was a loner who worked alone." Braden claims that Dulles gave Angleton permission to secretly bug important Washington dinner parties. "One time, Jim secretly bugged the house of the wife of a very senior Treasury Department official, who entertained important foreign guests and diplomatic corps people. Dulles got a big kick from reading Jim's report. Dulles was told about the bugging, but had no objection." (51)

Angleton spent his time protecting the security of CIA operations through research and careful analysis of incoming information. "The task meant that considerable amounts of paper must be acquired, read, digested, filed, and refiled. Ironically, although Angleton had helped develop the CIA's central registry (where names, reports, and cases were indexed), his staff had one of the worst records of any CIA component for contributing data into the main system after 1955. This was because of Angleton's obsession with secrecy and his inability to trust the security of the CIA's main filing system. He believed there was nothing to prevent someone from stealing from the CIA's storehouse of secrets. Keeping the best files to himself also helped consolidate his bureaucratic power." (52)

The only man Angleton shared this information with was Raymond Rocca, his head of the staff's new Research and Analysis Department. "Rocca's friends say he was well suited for the job. He had an excellent memory, and was considered a plodding, thorough scholar who usually provided Angleton with more detail than was needed.... Rocca reviewed the past with the devotion of an archeologist rediscovering an ancient tomb. Nearly every old Soviet intelligence case, dating back to the Cheka (the first Bolshevik secret police), was dutifully stored in the historical archives, and analyzed repeatedly... Critics of Angleton's methodology say that both he and Rocca wasted enormous quantities of time studying the gospels of prewar Soviet intelligence operations at the very moment that the KGB had shifted the style and emphasis of its operations against the West." (53)

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He argued: " Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient co-operation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed this concept or tried to prove his viewpoint, and the correctness of his position, was doomed to removal from the leading collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation. This was especially true during the period following the 17th Party Congress, when many prominent Party leaders and rank-and-file Party workers, honest and dedicated to the cause of communism, fell victim to Stalin's despotism."

James Jesus Angleton leaked doctored versions of the speech to numerous foreign government in a disinformation campaign. Charles J.V. Murphy has argued: "Many of Angleton's covert operations after he joined the CIA remain secret. The only people who know what he really did are his superiors and those who worked with him. One exploit that can be told came early in 1956. In collaboration with a friendly intelligence service, his unit acquired a copy of Nikita Khrushchev's famed denunciation of Stalin to the 20th Party Congress." (54)

Anatoli Golitsyn - Soviet Defector

In December 1961, Anatoli Golitsyn, a member of staff at the Soviet embassy in Helsinki, Finland, walked into the American embassy and asked for political asylum. (55) Golitsyn was immediately flown to the United States and lodged in a safe house called Ashford Farm near Washington. CIA officers found him as being "unpleasant and egotistical". They also commented that as a major in the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, he was "almost too fortunate and too high up to have a reason to defect". Golitsyn demanded that he be interviewed by James Jesus Angleton. He insisted that no one else in the CIA was smart enough or knew enough to question him. Attorney General Robert Kennedy went to see Golitsyn and was told that the CIA was deliberately keeping him away from Angleton. He promised to take up the case with President John F. Kennedy. (56)

As a result of President Kennedy's intervention, Golitsyn was interviewed by Angleton. A fellow officer, Edward Perry, later recalled: "With the single exception of Golitsyn, Angleton was inclined to assume that any defector or operational asset in place was controlled by the KGB." Angleton and his staff began debriefing Golitsyn. He told Angleton: "Your CIA has been the subject of continuous penetration... A contact agent who served in Germany was the major recruiter. His code name was SASHA. He served in Berlin... He was responsible for many agents being taken by the KGB." (57) In these interviews Golitsyn argued that as the KGB would be so concerned about his defection, they would attempt to convince the CIA that the information he was giving them would be completely unreliable. He predicted that the KGB would send false defectors with information that contradicted what he was saying.

James Jesus Angleton later told a Senate Committee: "Golitsyn possesses an unusual gift for the analytical. His mind without question is one of the finest of an analytical bent... and he is a trained historian by background. It is most difficult to dispute with him an historical date or event, whether it pertains to the Mamelukes or Byzantine or whatever it may be. He is a true scholar. Therefore, he is very precise in terms of what he states to be fact, and he separates the fact from speculation although he indulges in many avenues and so on." (58)

Peter Wright, the author of Spycatcher (1987) has argued that Angleton believed Golitsyn: "A string of senior CIA officers, most notably Dave Murphy, the head of the Soviet Division, unfairly fell under suspicion, their careers ruined. In the end, the situation became so bad, with so many different officers under suspicion as a result of Golitsyn's leads, that the CIA decided the only way of purging the doubt was to disband the Soviet Division, and start again with a completely new complement of officers. It was obviously a way out of the maze, but it could never justify the damage to the morale in the Agency as a whole." (59)

Defection of Kim Philby

On 23rd January, 1963, Kim Philby fled to Moscow. Nicholas Elliott later claimed that he and MI6 were surprised by the defection. "It just didn't dawn on us." (60) Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014) argues: "This defies belief. Burgess and Maclean had both defected... Philby knew he now faced sustained interrogation, over a long period, at the hands of Peter Lunn, a man he found unsympathetic. Elliott had made it quite clear that if he failed to cooperate fully, the immunity deal was off and the confession he had already signed would be used against him... There is another, very different way to read Elliott's actions. The prospect of prosecuting Philby in Britain was anathema to the intelligence services; another trial, so soon after the Blake fiasco, would be politically damaging and profoundly embarrassing." (61)

Desmond Bristow, MI6's head of station in Spain, agreed with this analysis: "Philby was allowed to escape. Perhaps he was even encouraged. To have him brought back to England and convicted as a traitor would have been even more embarrassing; and when they convicted him, could they really have hanged him?" (62) Yuri Modin, who was the man the KGB selected to talk to Philby before he defected, also believes this was the case: "To my mind the whole business was politically engineered. The British government had nothing to gain by prosecuting Philby. A major trial, to the inevitable accompaniment of spectacular revelation and scandal, would have shaken the British establishment to its foundations." (63)

James Jesus Angleton, who had been loyal defender for many years was extremely embarrassed. Philby and Angleton had thirty-six meetings at CIA headquarters between 1949 and 1951. Every one of the discussions that they had were typed up by Angleton's secretary Gloria Loomis. This was also true of the weekly meeting they had at Harvey's Restaurant in Washington. Angleton was so ashamed about all the CIA secrets he had given to Philby he destroyed all these documents. Angleton told Peter Wright: "I had them burned. It was all very embarrassing." He added that if he were a chap who murdered people he would kill Philby. (64)

Leonard McCoy, a senior officer in the CIA, later told Tom Mangold: "My guess is that he must have inadvertently leaked a lot to Philby. During those long boozy lunches and dinners. Philby must have picked him clean on CIA gossip, internal power struggles, and more importantly, personality assessments... At that time, the CIA had active operations going in Albania, the Baltic, the Ukraine, and from Turkey into southern Russia. We had agents parachuting in, floating in, walking in, boating in. Virtually all of these operations were complete failures. After the war, we had also planted a whole stay-behind network of agents in eastern Europe. They were all rolled up. It's difficult to draw conclusions why they all failed, but Philby must have played his part." (65)

CIA agent, Miles Copeland, was aware of these regular meetings. He later commented: "What Philby provided was feedback about the CIA's reactions. They (the KGB) could accurately determine whether or not reports fed to the CIA were believed or not... what it comes to, is that when you look at the whole period from 1944 to 1951, the entire Western intelligence effort, which was pretty big, was what you might call minus advantage. We'd have been better off doing nothing." (66)

It is believed that the defection of Kim Philby was partly responsible for his paranoia. Dr. Jerrold Post, a psychologist who knew Angleton later commented: "There's little doubt it would have contributed to his paranoia. He must have wondered if he could ever trust anyone again. Psychologically, it would have been a major event. If you give or invest your friendship to a person and he betrays that investment as cynically as Philby betrayed Angleton's, then future trust has gone." (67) Another top CIA psychologist, Dr. John Gittinger, claimed: "It absolutely shattered Angleton's life in terms of his ability to be objective about other people. It's like being devoted to your wife and finding her in bed with another man. There's nothing worse than a disillusioned idealist." (68)

The Assassination of John F. Kennedy

When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in November 1963, Richard Helms was given the responsibility of investigating Lee Harvey Oswald and the CIA. Helms initially appointed John M. Whitten to undertake the agency's in-house investigation. After talking to Winston Scott, the CIA station chief in Mexico City, Whitten discovered that Oswald had been photographed at the Cuban consulate in early October, 1963. Scott had not reported this matter to Whitten, his boss, at the time. Nor had Scott told Whitten that Oswald had also visited the Soviet Embassy in Mexico. In fact, Whitten had not been informed of the existence of Oswald, even though there was a 201 pre-assassination file on him that had been maintained by the Counterintelligence/Special Investigative Group. (69)

Whitten and his staff of 30 officers, were sent a large amount of information from the FBI. According to Gerald D. McKnight "the FBI deluged his branch with thousands of reports containing bits and fragments of witness testimony that required laborious and time-consuming name checks." Whitten later described most of this FBI material as "weirdo stuff". As a result of this initial investigation, Whitten told Helms that he believed that Oswald had acted alone in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. (70)

On 6th December, Nicholas Katzenbach invited Whitten and Birch O'Neal, Angleton's trusted deputy and senior Special Investigative Group (SIG) officer to read Commission Document 1 (CD1), the report that the FBI had written on Lee Harvey Oswald. Whitten now realized that the FBI had been withholding important information on Oswald from him. He also discovered that Richard Helms had not been providing him all of the agency's available files on Oswald. This included Oswald's political activities in the months preceding the assassination. (71)

John M. Whitten had a meeting where he argued that Oswald's pro-Castro political activities needed closer examination, especially his attempt to shoot the right-wing General Edwin Walker, his relationship with anti-Castro exiles in New Orleans, and his public support for the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee. "None of this had been passed to us." Whitten added that has he had been denied this information, his initial conclusions on the assassination were "completely irrelevant." (72)

Helms responded by taking Whitten off the case. James Jesus Angleton was now put in charge of the investigation. According to Gerald McKnight, the author of Breach of Trust (2005), Angleton "wrested the CIA's in-house investigation away from John Whitten because he either was convinced or pretended to believe that the purpose of Oswald's trip to Mexico City had been to meet with his KGB handlers to finalize plans to assassinate Kennedy." As McKnight explains: "Angleton, like his professional counterpart, Hoover, dropped the Cuban angle in the assassination and turned the investigation over to Counterintelligence's Soviet Division to determine whether the KGB had influenced Oswald in any way." (73)

The Warren Commission

Over the next few months James Jesus Angleton worked with William Sullivan of the FBI in providing information to the Warren Commission. During this period Angleton continued to interview Anatoli Golitsyn. Golitsyn argued that the KGB sought a virtual takeover of Western intelligence services and had turned several CIA agents. Angleton was convinced by this story and as Tom Mangold, the author of Cold Warrior: James Jesus Angleton: The CIA's Master Spy Hunter (1991) has pointed out: "With these revelations, a minor and undistinguished KGB officer, working in tandem with the CIA's chief of Counterintelligence was now able to throw the CIA and much of Western intelligence into a decade of deep confusion and doubt. The acceptance of Golitsyn's logic led to the betrayal and dismissal of some of the CIA's finest officers and agents." (74)

In January 1964 Yuri Nosenko, deputy chief of the Seventh Department of the KGB, who had been providing information since 1961, contacted the CIA and said he wanted to defect to the United States. He claimed that he had been recalled to Moscow to be interrogated. Nosenko feared that the KGB had discovered he was a double-agent and once back in the Soviet Union would be executed. He claimed that he had been put in charge of the KGB investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald. He denied the Oswald had any connection with KGB. After interviewing Oswald it was decided that he was not intelligent enough to work as a KGB agent. They were also concerned that he was "too mentally unstable" to be of any use to them. Nosenko added that the KGB had never questioned Oswald about information he had acquired while a member of the U.S. Marines. This surprised the CIA as Oswald had worked as a Aviation Electronics Operator at the Atsugi Air Base in Japan. (75)

J. Edgar Hoover welcomed the information from Nosenko: "Nosenko's assurances that Yekaterina Furtseva herself had stopped the KGB from recruiting Oswald gave Hoover the evidence he needed to clear the Soviets of complicity in the Kennedy murder - and, even more from Hoover's point of view, clear the FBI of gross negligence. Hoover took this raw, unverified, and untested intelligence and leaked it to members of the Warren Commission and to President Johnson." (76) Hoover leaked this information to the Warren Commission. This pleased its members as it helped to confirm the idea that Oswald had acted alone and was not part of a Soviet conspiracy to kill John F. Kennedy.

Despite the fact that the Warren Commission received information from Hoover about Yuri Nosenko his name is not mentioned in the final report. Although the commission favoured Hoover’s interpretation that he was a genuine defector, it was decided that it was better not to include the information. This was decided after Nosenko’s CIA case-officer, Tennant Bagley, spoke to commission members on 24th July, 1964: “Nosenko is a KGB plant and may be publicly exposed as such some time after the appearance of the Commission’s report. Once Nosenko is exposed as a KGB plant, there will arise the danger that his information will be mirror-read by the press and public, leading to conclusions that the USSR did direct the assassination.” (77)

According to Mark Riebling: “That was enough to settle the question. The commission had been founded for no other reason to avert rumors which might cost ‘forty million lives’, and later that afternoon decided it would be ‘undesirable to include any Nosenko information’ information’ in its report. The defector’s FBI debriefings would remain classified in commission files.” Richard Helms points out that Hoover was not happy with this decision: “When the Warren people sided with us, it cut across Mr. Hoover’s assertion that the Russians had had nothing to do with the assassination.” (78)

Some researchers have claimed that Angleton was involved in covering up CIA's involvement in the assassination of Kennedy. H. R. Haldeman, President Nixon's chief of staff, claimed in his book, The Ends of Power: "After Kennedy was killed, the CIA launched a fantastic cover-up. The CIA literally erased any connection between Kennedy's assassination and the CIA... in fact, Counter intelligence Chief James Angleton of the CIA called Bill Sullivan of the FBI and rehearsed the questions and answers they would give to the Warren Commission investigators." (79)

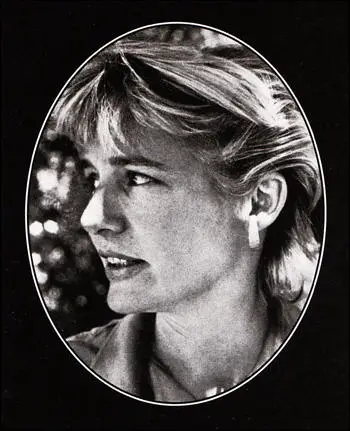

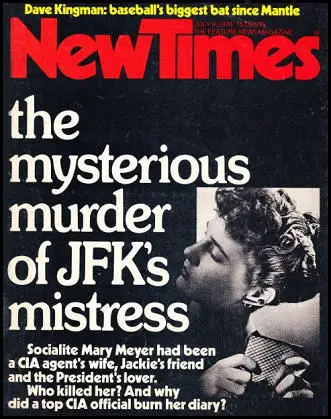

Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer

Timothy Leary has claimed that a few days after John F. Kennedy had been killed he received a disturbing phone call from Mary Pinchot Meyer. He wrote in his autobiography, Flashbacks (1983): Ever since the Kennedy assassination I had been expecting a call from Mary. It came around December 1. I could hardly understand her. She was either drunk or drugged or overwhelmed with grief. Or all three." Meyer told Leary: "They couldn't control him any more. He was changing too fast. They've covered everything up. I gotta come see you. I'm afraid." (80)

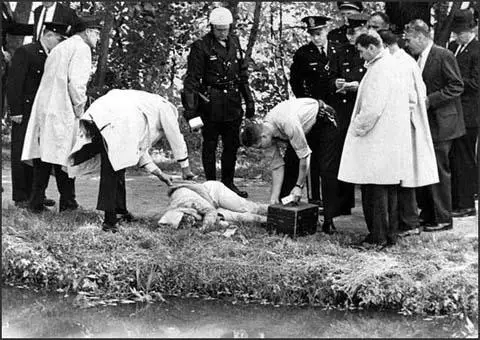

On 12th October, 1964, Mary Pinchot Meyer was shot dead as she walked along the Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Henry Wiggins, a car mechanic, was working on a vehicle on Canal Road, when he heard a woman shout out: "Someone help me, someone help me". He then heard two gunshots. Wiggins ran to the edge of the wall overlooking the towpath. He later told police he saw "a black man in a light jacket, dark slacks, and a dark cap standing over the body of a white woman." (81)

Mary appeared to be killed by a professional hitman. The first bullet was fired at the back of the head. She did not die straight away. A second shot was fired into the heart. The evidence suggests that in both cases, the gun was virtually touching Mary’s body when it was fired. As the FBI expert testified, the “dark haloes on the skin around both entry wounds suggested they had been fired at close-range, possibly point-blank”. (82)

Ben Bradlee points out that the first he heard of the death of Mary Pinchot Meyer was when he received a phone-call from Wistar Janney, his friend who worked for the CIA: "My friend Wistar Janney called to ask if I had been listening to the radio. It was just after lunch, and of course I had not. Next he asked if I knew where Mary was, and of course I didn't. Someone had been murdered on the towpath, he said, and from the radio description it sounded like Mary. I raced home. Tony was coping by worrying about children, hers and Mary's, and about her mother, who was seventy-one years old, living alone in New York. We asked Anne Chamberlin, Mary's college roommate, to go to New York and bring Ruth to us. When Ann was well on her way, I was delegated to break the news to Ruth on the telephone. I can't remember that conversation. I was so scared for her, for my family, and for what was happening to our world. Next, the police told us, someone would have to identify Mary's body in the morgue, and since Mary and her husband, Cord Meyer, were separated, I drew that straw too." (83)

Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) has questioned this account of events provided by Bradlee. "How could Bradlee's CIA friend have known 'just after lunch' that the murdered woman was Mary Meyer when the victim's identity was still unknown to police? Did the caller wonder if the woman was Mary, or did he know it, and if so, how? This distinction is critical, and it goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding Mary Meyer's murder." (84)

That night Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee received a telephone call from Mary's best friend, Anne Truitt, an artist living in Tokyo. She told her that it "was a matter of some urgency that she found Mary's diary before the police got to it and her private life became a matter of public record". (85) Mary had apparently told Anne that "if anything ever happened to me" you must take possession of my "private diary". Ben Bradlee explains in The Good Life (1995): "We didn't start looking until the next morning, when Tony and I walked around the corner a few blocks to Mary's house. It was locked, as we had expected, but when we got inside, we found Jim Angleton, and to our complete surprise he told us he, too, was looking for Mary's diary." (86)

James Jesus Angleton later claimed that he had also received a telephone call from Anne Truitt. His wife, Cicely Angleton, confirmed this in an interview given to Nina Burleigh. (87) However, an article by Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, in the New Times on 9th July, 1976, gives a different version of events with the Angleton's arriving at Mary's house that evening to attend a poetry reading and that at this stage they did not know she was dead. (88)

Joseph Trento, the author of Secret History of the CIA (2001), has pointed out: "Cicely Angleton called her husband at work to ask him to check on a radio report she had heard that a woman had been shot to death along the old Chesapeake and Ohio towpath in Georgetown. Walking along that towpath, which ran near her home, was Mary Meyer's favorite exercise, and Cicely, knowing her routine, was worried. James Angleton dismissed his wife's worry, pointing out that there was no reason to suppose the dead woman was Mary - many people walked along the towpath. When the Angletons arrived at Mary Meyer's house that evening, she was not home. A phone call to her answering service proved that Cicely's anxiety had not been misplaced: Their friend had been murdered that afternoon." (89)

A Soviet Mole

Angleton became convinced that the CIA had been penetrated by a "mole" working for the KGB. He ordered, Clare Edward Petty, a member of the ultra-secret Special Investigation Group (SIG), to carry out a study into the possibility that a Soviet spy existed in the higher levels of the CIA. Angleton suggested that Petty should take a close look at David Edmund Murphy. The Soviet defector, Anatoli Golitsyn, had suggested that Murphy might have been recruited as a spy when working in Berlin in the 1950s. Angleton's suspicions were increased by Murphy speaking fluent Russian and marrying a woman who had previously lived in the Soviet Union. (90)

Murphy had been accused of being a Soviet spy by one of his own officers, Peter Kapusta. He originally expressed this opinion to Sam Papich, the FBI's liaison man with the CIA. "Kapusta called in the middle of the night. It was one or two o'clock in the morning. The FBI did not investigate. From the beginning, the bureau looked at the Murphy matter strictly as an internal CIA problem. We received certain information, including Kapusta's input. By our standards, based on what was available, FBI investigation was not warranted." (91) This information was passed to Angleton and he became convinced that he was a Soviet mole.

Petty investigated Murphy's wife and found that her family had fled from Russia after the Russian Revolution. They moved to China before settling in San Francisco. Petty could find no evidence that she was pro-communist. Newton S. Miler, a member of SIG had investigated Murphy in the early 1960s. He discovered that a large number of his operations had been unsuccessful: "Just a series of failures, things that blew up in his face. Odd things that happened. The scrapes in Japan and Vienna. They (the KGB) may have been setting up Murphy just to embarrass CIA. But you have to consider these incidents may have been staged to give him bona fides." (92) Petty came to the conclusion that Murphy was "accident prone".

Petty eventually produced a twenty-five-page report that concluded that there was a "probability" that Murphy was innocent. Petty felt that Murphy may have been targeted by the KGB, but was never recruited. (93) However, Angleton rejected the report as he was convinced he was a spy. In 1968 Angleton arranged for Murphy to be removed from his job as head of the Soviet Division and assigned to Paris as station chief. Angleton then contacted the head of French intelligence and warned him that Murphy was a Soviet agent. (94)

Tennant Bagley

Angleton now asked Petty to investigate his close colleague, Tennant Bagley, who had been the case-officer dealing with Yuri Nosenko. This was a surprising suggestion as Bagley had always been a loyal supporter of Angleton and told the Warren Commission that “Nosenko is a KGB plant and may be publicly exposed as such some time after the appearance of the Commission’s report. Once Nosenko is exposed as a KGB plant, there will arise the danger that his information will be mirror-read by the press and public, leading to conclusions that the USSR did direct the assassination.” (95)

However, Angleton believed that Bagley had deliberately mishandled the attempted recruitment of a minor Polish intelligence officer in Switzerland. "Petty fastened on an episode that had taken place years earlier, when Bagley had been stationed in Bern, handling Soviet operations in the Swiss capital. At the time, Bagley was attempting to recruit an officer of the UB, the Polish intelligence service, in Switzerland. Petty concluded that a phrase in a letter from Michal Goleniewski, the Polish intelligence officer who called himself Sniper... the KGB had advance knowledge that could only have come from a mole in the CIA." (96)

Petty spent a year investigating Bagley, who had remained one of Angleton's strongest supporters. Petty's 250 page report on Bagley concluded that he "was a candidate to whom we should pay serious attention". However, Angleton rejected the report and told Petty: "Pete's not a KGB agent, he's not a Soviet spy." As Tom Mangold, the author of Cold Warrior: James Jesus Angleton: The CIA's Master Spy Hunter (1991) has pointed out: "A lesser man than Petty might have given up at this stage. He had investigated, on his master's behalf, a former chief and deputy chief of the Soviet Division - incredible targets in themselves - and had failed to prove either case. But Petty remained convinced that a mole existed." (97)

James Jesus Angleton - Soviet Spy?

Clare Edward Petty continued to search for the Soviet mole and eventually reached the conclusion that it was the man who had ordered the investigation, James Jesus Angleton, who had penetrated the CIA, and was in league with Anatoli Golitsyn, who was not a genuine defector: "It was at that point that I decided I'd been looking at it all wrong by assuming Golitsyn was good as gold. I began rethinking everything. If you turned the flip side it all made sense. Golitsyn was sent to exploit Angleton. Then the next step, maybe not just an exploitation, and I had to extend it to Angleton. Golitsyn might have been dispatched as the perfect man to manipulate Angleton or provide Angleton with material on the basis of which he (Angleton) could penetrate and control other services.... Angleton made available to Golitsyn extensive sensitive information which could have gone back to the KGB. Angleton was a mole, but he needed Golitsyn to have a basis on which to act.... Golitsyn and Angleton. You have two guys absolutely made for each other. Golitsyn was a support for things Angleton had wanted to do for years in terms of getting into foreign intelligence services. Golitsyn's leads lent themselves to that. I concluded that logically Golitsyn was the prime dispatched agent." (98)

In 1971 Petty began "putting stuff on index cards, formulating my theory". Petty later told David C. Martin: The case against Angleton was a great compilation of circumstantial material. It was not a clear-cut case." However, an unnamed senior CIA officer explained to Martin that his investigation of Angleton was deeply flawed: "There was a lot of supposition, factual situations which were subject to varying interpretations. You could draw conclusions one way or the other, and we felt the conclusions by the fellow who was making the case were overdrawn... Petty was a very intense person. He was seized with this theory, and like all people in this field, once they get seized with this thing, you wonder whether they're responsible or not." (99) Newton S. Miler, a member of SIG supported this view: "Petty... would decide on a bottom line before he started and then fit everything to his conclusions. He wanted recognition, he wanted to be seen as a spycatcher. In the end, he turned against everyone, and even had disputes with Ray Rocca and myself. I always thought Ed a bit odd." (100)

Petty told James H. Critchfield, the CIA head of the Eastern European and Near East divisions about his suspicions. As he later pointed out: "I reviewed Angleton's entire career, going back through his relationships with Philby, his adherence to all of Golitsyn's wild theories, his false accusations against foreign services and the resulting damage to the liaison relationships, and finally his accusation against innocent Soviet Division officers." As a result of his investigation, Petty concluded that there was an "80-85 percent probability" that Angleton was a Soviet mole.

Clare Edward Petty decided not to tell his boss, Jean M. Evans, about his investigation. "Petty worked in absolute secrecy, never revealing to anyone except Critchfield that he was gathering information to accuse his own boss, James Angleton, as a Soviet spy. By the spring of 1973, after toiling for some two years, Petty felt he could not develop his theory any further. He decided to retire." (101)

Harold Wilson Plot

James Jesus Angleton became convinced that Anatoli Golitsyn was the most important Soviet defector. Angleton's colleague, E. Henry Knoche, claimed: "Angleton had a special view of the world. You almost have to be 100 per cent paranoid to do the job. You always have to fear the worst. You always have to assume, without necessarily having the proof in your hands, that your own organization has been penetrated and there's a mole around somewhere. And it creates this terrible distrustful attitude." (102)

He believed the story that Hugh Gaitskell had been murdered in January 1963 to allow Harold Wilson, a KGB agent, to become leader of the Labour Party. Angleton believed Golitsyn but few senior members of the CIA agreed with him. They pointed out that Gaitskell had died after Golitsyn had left the Soviet Union and would have had to know in advance what was about to take place.

However, Angleton remained convinced and according to David Leigh, the author of The Wilson Plot (1988) argues that Angleton developed a "fanatical belief that Wilson was under Soviet control". (103) Angleton passed this information onto Peter Wright and Arthur Martin of MI5. Wright admitted in his biography that he had been suspicious of Gaitskell's death at the time: "I knew him personally and admired him greatly... After he died his doctor got in touch with MI5 and asked to see somebody from the Service. Arthur Martin, as the head of Russian Counter-espionage, went to see him. The doctor explained that he was disturbed by the manner of Gaitskell's death. He said that Gaitskell had died of a disease called lupus disseminata, which attacks the body's organs. He said that it was rare in temperate climates and that there was no evidence that Gaitskell had been anywhere recently where he could have contracted the disease." (104)

In 1968 Wright joined forces with Cecil King, the newspaper publisher, in a plot to bring down the government of Harold Wilson and replace it with a coalition led by Lord Mountbatten. According to Ken Livingstone: "Matters began to hot up when the press baron Cecil King, a long-standing MI5 agent, began to discuss the need for a coup against the Wilson Government. King informed Peter Wright that the Daily Mirror would publish any damaging anti-Wilson leaks that MI5 wanted aired, and at a meeting with Lord Mountbatten and the Government's chief scientific adviser, Solly Zuckerman, he urged Mountbatten to become the leader of a Government of national salvation." (105) Solly Zuckerman got up and before he left said: "This is rank treachery. All this talk of machine guns at street corners is appalling." Zuckerman told Mountbatten not to have anything to do with the conspiracy and as a result it ended in failure. (106)

James Schlesinger

In February, 1973, James Schlesinger replaced Richard Helms as Director of the CIA. Angleton immediately went to see Schlesinger and gave him a list of more than 30 people that he considered to be Soviet agents. This list included top politicians, foreign intelligence officials and senior CIA officials. Those named included Harold Wilson, the British prime minister, Olof Palme, the Swedish prime minister, Willy Brandt, chairman of the West German Social Democratic Party, Averell Harriman, the former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Lester Pearson, the Canadian prime minister, Armand Hammer, the chief executive of Occidental Petroleum Corporation and Henry Kissinger, the National Security Adviser and Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon. (107)

Schlesinger listened to Angleton for seven hours. After consulting with other senior figures in the CIA he concluded that he was suffering from paranoia. However, he liked Angleton and decided against forcing him into retirement. Schlesinger later recalled: "Listening to him was like looking at an Impressionist painting... Jim's mind was devious and allusive, and his conclusions were woven in a quite flimsy manner. His long briefings would wander on, and although he was attempting to convey a great deal, it was always smoke, hints, and bizarre allegations. He might have been a little cracked but he was always sincere." (108)

Schlesinger discovered that Angleton had been running Operation Chaos since 1967. President Lyndon B. Johnson had ordered the CIA to determine whether the anti-Vietnam War movement was being financed or manipulated by foreign governments. Angleton put Richard Ober in charge of the project that collected information on the peace movement, New Left activists, campus radicals and black nationalists. The CIA joined forces with the FBI to spy on these people: "The agencies buried their long-standing rivalries to cooperate on mail intercepts, phone taps, monitoring meetings, the use of LSD to pump people for information, and surveillance of... expatriates as well as travelers passing through certain select areas abroad." (109)

James Jesus Angleton was ordered to attend a meeting in his office. Schlesinger demanded to know what this large and expensive project had yielded. When he was given the answer, "Not very much," he ordered Angleton to stop the entire operation. Apparently he told him: "Jim, this thing is not only breaking the law, but we're getting nothing out of it." (110) On 9th May, 1973, James Schlesinger issued a directive to all CIA employees: “I have ordered all senior operating officials of this Agency to report to me immediately on any activities now going on, or might have gone on in the past, which might be considered to be outside the legislative charter of this Agency. I hereby direct every person presently employed by CIA to report to me on any such activities of which he has knowledge. I invite all ex-employees to do the same. Anyone who has such information should call my secretary and say that he wishes to talk to me about “activities outside the CIA’s charter”. (111)

HT-LINGUAL

In early 1973, James Schlesinger appointed William Colby as head of all clandestine operations. Colby was now Angleton's direct superior. One of his first actions was to take a close look at HT-LINGUAL, a huge secret mail-opening scheme, that Angleton had been running since November 1955. Angleton's staff were intercepting letters between the United States and the Soviet Union and other Communist countries. Angleton thought that it was "probably the most important overview that counter-intelligence had" because the "enemy regarded America's mails as inviolate, mail coverage was likely to provide clues to the identities of Soviet agents". Angleton was aware the mail-operating operation was illegal and that if it were ever exposed "serious public reaction in the United States would probably occur." (112)

Colby investigated HT-LINGUAL and discovered that over the last twenty years over 215,000 letters were opened in New York City alone. "Each morning three CIA officers reported to a special room at New York's LaGuardia Airport, where a postal clerk delivered from two to six sacks of mail... Working with a Diebold camera, the three officers photographed the exteriors of about 1,800 letters each day. Each evening they stashed about 60 of the letters in an attaché case or stuffed them in their pockets and took them to the CIA's Manhattan Field Office for opening." (113)

Colby later commented: I couldn't find it had produced anything... I wrote a memo saying it should be terminated." (114) Angleton questioned this decision and pointed out that they had been able to find out "whether illegal Soviet agents hidden in the United States were communicating to and from the USSR through the U.S. mails." (115) Schlesinger decided to "suspend it but not terminate it".

William Colby

In July 1973, James Schlesinger became President Nixon's Secretary of Defence and William Colby was appointed as the new Director of the CIA. Colby was a strong critic of Angleton's activities: "Colby had long believed that the true function of the agency was to collect and analyze information for the President and his policymakers. He maintained that it was not the CIA's function to fight the KGB; the KGB was merely an obstacle en route to scaling the walls surrounding the Politburo and the Central Committee. In Colby's mind, his concept of the CIA's mission was an article of faith. But in Angleton he saw only a KGB fighter and a failed spycatcher." (116)

Colby pointed out: "I couldn't find that we ever caught a spy under Jim. That really bothered me. Every time I asked the second floor about this question, I got 'Well, maybe' and 'Perhaps,' but nothing hard. Now I don't care what Jim's political views were as long as he did his job properly, and I'm afraid, in that respect, he was not a good CI chief. As far as I was concerned, the role of the Counterintelligence Staff was basically to secure penetrations into the Russian intelligence services and to debrief defectors. Now I'm not saying that's easy, but then CI was never easy. As far as this business of finding Soviet penetrations within the CIA, well, we have the whole Office of Security to protect us. That is their job... The isolation of the Counterintelligence Staff from the Soviet Division was a huge problem. Everyone knew it. The CI Staff was so far out on its own, so independent, that it had nothing to do with the rest of the agency, The staff was so secretive and self-contained that its work was not integrated into the rest of the agency's operations. There was a total lack of cooperation."

Colby told David Wise that he feared that Angleton would commit suicide if he was removed from his post. He therefore decided to gradually ease him out. He took away Angleton's control over proposed clandestine operations. This was followed by removing his power to review operations already in progress. As each of these roles were removed, the size of Angleton's staff dwindled from hundreds to some forty people. However, Angleton refused to resign: "Taking away FBI liaison and the other units was designed to lead him to see the handwriting on the wall. He just wouldn't take the bait." (117)

On 17th December, 1974, Colby called Angleton into his office and told him that he wanted him to retire. He offered him a post as a special consultant, in which he would compile his experiences for the CIA's historical record. "I told him to leave the staff to write up what he had done during his career. This reflected my desire to get rid of him, but in a dignified way - so he could get down his experience on paper. No one knew what he had done! I didn't! I told him to take either the consultancy or honorable retirement. We also discussed that he would get a higher pension if he accepted early retirement... He dug in his heels. I couldn't get him to leave the job on his own. I just couldn't edge him out." (118)

The following day Seymour Hersh, who worked for the New York Times, phoned Colby and told him that he had an important story about the CIA. The two men met on 20th December. Hersh revealed that he had discovered both of the domestic operations run by Angleton - HT-LINGUAL and Operation Chaos. "Hersh told Colby that he intended to publish the news that the CIA had engaged in a massive spying campaign against thousands of American citizens (which violated the CIA charter). Colby tried to contain the damage, and he attempted to correct some of the exaggerations Hersh had picked up. But, in so doing, he effectively confirmed Hersh's information." (119)

Colby now had a meeting with Angleton and told him that Hersh was about to publish a story about his illegal operations. As a result he was forced to sack him. Angleton went to a public pay phone and called Hersh. He begged him not to run the pending story. as an inducement, he promised to give the journalist other classified information to publish instead. "He told me he had other stories which were much better. He really wanted to buy me off with these leads. One of the things he offered sounded very real - he said it was about something the United States was doing inside the Soviet Union. It could have been totally poppycock, who knows. I didn't write it." Angleton later accused Colby of giving information about the illegal operations to Hersh. However, in his interview with Tom Mangold he denied it. (120)

On 22nd December, 1974, Seymour Hersh published his story in the New York Times. Angleton was identified as the head of the CIA's counter-intelligence staff and the man responsible for these illegal operations. David Atlee Phillips, saw him soon after the article was published: "We talked for a few minutes, standing in the diffused glow of a distant light. Angleton's head was lowered, but occasionally he glanced up from under his brim of his black homburg... We then rambled on about nothing particular. I thought to myself that I had never seen a man who looked so infinitely tired and sad." (121)

James Jesus Angleton Files

George T. Kalaris was appointed to replace James Jesus Angleton. William Colby pointed out: "I put George in there because he's a very good, straightforward fellow. He wasn't flashy. He knew how to run stations, and I had trust and faith in him. The situation needed a sensible person like him to put the place together again after all the chaos. I also needed someone who had not taken a side on any of the major issues.... I wrote George a very basic memorandum of instruction. I ordered him to go to it - to go get agents, to go penetrate the enemy." (122)

Angleton went to see Kalaris on 31st December, 1974. He told the new head of counter-intelligence that he intended to "crush" him. "It's nothing personal. It's just that you are caught in the middle of a big battle between Colby and me. I feel sorry for you. I studied your personnel records, and I repeat, you are going to be crushed." Angleton then went on to criticize the choice of Kalaris to run the department: "To qualify for working on my staff you would need eleven years of continuous study of old cases, starting with The Trust and the Rote Kapelle and so on. Not ten years, not twelve, but precisely eleven. My staff has made detailed study of these requirements. And even that much experience would make you only a journeyman counter-intelligence analyst." Angleton then went on to say that the Soviets had not been successful in compromising the CIA's Counter-intelligence Staff, because he had been there to protect it. "But this is not true of the Soviet Division". (123)

Kalaris now instigated an investigation into Angleton's filing system. His team found "entire sets of vaults and sealed rooms scattered all around the second and third floors of CIA headquarters". They came across over 40 safes, some of them had not been opened for over ten years. No one on Angleton's remaining staff knew what was in them and no one had the combinations anymore. Kalaris was forced to call in a "crack team of safebusters to drill open the door". The investigators found "Angleton's own most super-sensitive files, memoranda, notes and letters... tapes, photographs" and according to Kalaris "bizarre things of which I shall never ever speak". This included files on two senior figures in MI5, Sir Roger Hollis and Graham Mitchell. There were also files on a large number of journalists. (124)

The investigators also found documents concerning Lee Harvey Oswald and on 18th September, 1975, George T. Kalaris wrote a memo to the executive assistant to the deputy director of Operations of the CIA describing the contents of Oswald's 201 file. "There is also a memorandum dated 16 October 1963 from (redacted but likely Winston Scott) to the United States Ambassador there concerning Oswald's visit to Mexico City and to the Soviet Embassy there in late September - early October 1963. Subsequently there were several Mexico City cables in October 1963 also concerned with Oswald's visit to Mexico City, as well as his visits to the Soviet and Cuban Embassies." (125) As John Newman, the author of Oswald and the CIA (2008) has pointed out: "the significance of the Kalaris memo is that it disclosed the existence of pre assassination knowledge of Oswald's activities in the Cuban Consulate, and that this had been put into cables in October 1963." (126)

The investigators discovered that Angleton had not entered any of the official documents from these safes into the CIA's central filing system. Nothing had never been filed, recorded, or sent to the secretariat. "Angleton had been quietly building an alternative CIA, subscribing only to his rules, beyond peer review or executive supervision." Over the next three years "a team of highly trained specialists another three full years just to sort, classify, file, and log the material into the CIA system." Leonard McCoy, was giving the responsibility of inspected the most important files. McCoy was advised "to retain less than one half of 1 per cent of the total, or no more than 150-200 out of the 40,000." The rest of Angleton's files were then destroyed. (127)

James Truitt

James Truitt gave an interview to the National Enquirer that was published on 23rd February, 1976, with the headline, "Former Vice President of Washington Post Reveals... JFK 2-Year White House Romance". Truitt told the newspaper that Mary Pinchot Meyer was having an affair with John F. Kennedy. He also claimed that Mary had told them that she was keeping an account of this relationship in her diary. Truitt added that the diary had been removed by James Jesus Angleton and Ben Bradlee when Meyer was murdered on 12th October, 1964. (128)

The newspaper sent a journalist to interview Bradlee about the issues raised by Truitt. According to one eyewitness account, Bradlee "erupted in a shouting rage and had the reporter thrown out of the building". Nina Burleigh claims that it was Watergate that motivated Truitt to give the interview. "Truitt was disgusted that Bradlee was getting credit as a great champion of the First Amendment for exposing Nixon's steamy side in Watergate coverage after having indulgently overlooked Kennedy's hypocrisies." Truitt was also angry that Bradlee had not exposed Kennedy's affair with Mary Pinchot Meyer in his book, Conversations with Kennedy. Truitt had been close to Meyer during this period and had received a considerable amount of information about the relationship. (129)

Ben Bradlee, who had gone on holiday with his new wife, Sally Quinn, gave orders for the Washington Post to ignore the story. However, Harry Rosenfeld, a senior figure at the newspaper, commented, "We're not going to treat ourselves more kindly than we treat others." (130) However, when the article was published it included several interviews with Kennedy's friends who denied he had an affair with Meyer. Kenneth O'Donnell described her as a "lovely lady" but denied that there had been a romance. Timothy Reardon claimed that "nothing like that ever happened at the White House with her or anyone else." (131)

Bradlee and James Jesus Angleton continued to deny the story. Some of Mary's friends knew that the two men were lying about the diary and some spoke anonymously to other newspapers and magazines. Later that month Time Magazine published an article confirming Truitt's story. (132) In an interview with Jay Gourley, Bradlee's former wife, and Mary's sister, Antoinette Pinchot Bradlee admitted that her sister had been having an affair with John F. Kennedy: "It was nothing to be ashamed of. I think Jackie might have suspected it, but she didn't know for sure." (133)

Two journalists, Ron Rosenbaum and Phillip Nobile, decided to carry out their own investigation into the case. After interviewing James Truitt and several other friends of Mary Pinchot Meyer, including the Angletons, they published an article, entitled, "The Curious Aftermath of JFK's Best and Brightest Affair" in the New Times on 9th July, 1976. According to this version, the search for the diary took place on Saturday, 17th October, five days after her murder. As well as Antoinette (Tony) Bradlee, James and Cicely Angleton, Cord Meyer and Anne Chamberlain, were also present. The search party found nothing. (134)

Later that same day, Tony Bradlee was said to have discovered a "locked steel box" in Mary's studio. Inside it was one one of Mary's artist sketchbooks, a number of personal papers and "hundreds of letters". Peter Janney, the author of Mary's Mosaic (2012) points out: "Tony Bradlee later claimed that the presence of a few vague notes written in the sketchbook - allegedly including cryptic references to an affair with the president - persuaded her that she'd found her sister's missing diary. But Mary's artist sketchbook wasn't her real diary. It was just a ruse." (135) The contents of the box were given to Angleton who claimed he burnt the diary.

Investigation by Cleveland Cram

In 1976 Cleveland Cram, the former Chief of Station in the Western Hemisphere, met Ted Shackley and George T. Kalaris at a cocktail party in Washington. Kalaris, who had replaced Angleton as Chief of Counterintelligence, asked Cram if he would like to come back to work. Cram was told that the CIA wanted a study done of Angleton's reign from 1954 to 1974. "Find out what in hell happened. What were these guys doing." (136)

Cram took the assignment and was given access to all CIA documents on covert operations. The study took six years to complete. In one section, Cram looks at the reliability of information found in books about the American and British intelligence agencies. Cram praises certain authors for writing accurate accounts of these covert activities. He is especially complimentary about the books written by David C. Martin, the author of Wilderness of Mirrors (1980), Tom Mangold the author of Cold Warrior (1991) and David Wise the author of Molehunt (1992). Cram points out that these authors managed to persuade former CIA officers to tell the truth about their activities. In some cases, they were even given classified documents.

Cram is highly critical of the work of Edward J. Epstein, the author of Legend: The Secret World of Lee Harvey Oswald (1978). Cram makes it clear that Epstein, working with James Jesus Angleton, was part of a disinformation campaign. Cram writes: “Edward J. Epstein's Legend: The Secret World of Lee Harvey Oswald provided enormous stimulus to the deception thesis by suggesting that Yuri Nosenko, a Soviet defector, had been sent by the KGB to provide a cover story for Lee Harvey Oswald, who the book alleged was a KGB agent.... Epstein's suggested that Nosenko's defection from the KGB was in reality a mission to provide a cover story for Oswald, which would absolve the Soviet Government of complicity in the assassination of President Kennedy." (137)

Cram is equally dismissive of Epstein's book, Deception: The Invisible War Between the KGB and the CIA (1989): "Like Legend, it is propaganda for Angleton and essentially dishonest. The errors are too many to document here... In summary, this is one of many bad books inspired by Angleton after his dismissal that have little basis in fact. An interview with Epstein in Vanity Fair magazine in May 1989 suggests he too has had second thoughts about Angleton and even about Golitsyn, his pet defector. Epstein admitted that Golitsyn shaped Angleton's views and possibly was a liar." (138)

Cleveland Cram investigation lasted six years. According to David Wise "The names of the mole suspects were considered so secret that their files were kept in locked safes in yet another vault directly across from Angleton's office... Cram... produced twelve legal-sized volumes, each three hundred to four hundred pages. Cram's approximately four-thousand-page study has never been declassified. It remains locked in the CIA's vaults." (139) However, a 71 page report, Of Moles and Molehunters: A Review of Counterintelligence Literature, was declassified in 2003.

The Church Committee