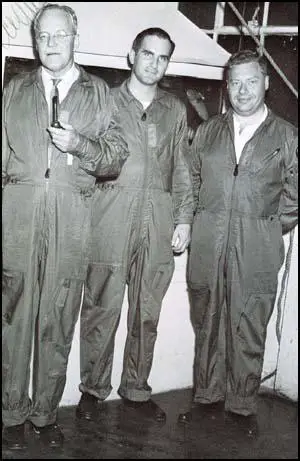

Ray S. Cline

Ray Steiner Cline was born in 1919. He studied at Harvard University before joining the Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War. In 1944 he was appointed as Chief of Current Intelligence. Later he was sent to China where he worked with John K. Singlaub, Richard Helms, E. Howard Hunt, Mitchell WerBell, Paul Helliwell, Robert Emmett Johnson and Lucien Conein. Others working in China at that time included Tommy Corcoran, Whiting Willauer and William Pawley.

In 1946 Cline was assigned to the Operations Division of the War Department General Staff to write its history. Cline joined the Central Intelligence Bureau in 1949 and eventually became Chief of the Office of National Estimates. He also served in Britain (1951-53) under Brigadier General Thomas Betts. Cline became Chief of station in Taiwan in 1957. A post he held for over four years.

In 1962 Cline was appointed as Deputy Director for Intelligence for the CIA. He became disillusioned with Lyndon B. Johnson and he requested a move from Washington. In 1966 Richard Helms managed to arrange for Clines to become Special Coordinator and Adviser to the Ambassador in the U.S. Embassy in Bonn. From 1969 until his retirement in 1973, he was Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the Department of State during the Richard Nixon administration.

Cline played an important role in the forming of right-wing organizations such as the World Anti-Communist League and its U.S. chapter, the U.S. Council for World Freedom.

Cline has written several books including including World War Two, War Department(1951), World Power Assessment (1975), CIA: Reality v Myth (1981), Central Intelligence Agency Under Reagan, Bush and Casey (1982), Terrorism: The Soviet Connection (1985), Secrets, Spies and Scholars: The CIA from Roosevelt to Reagan (1986), Western Europe in Soviet Global Strategy (1987), Central Intelligence Agency: A Photographic History (1989), Chiang Ching-Kuo Remembered: The Man and His Political Legacy (1993).

In his book The Power of Nations in the 1990s: A Strategic Assessment (1995): "Americans must at long last face up to geopolitical verities. It is easy to recognize that the United States and the whole Western Hemisphere are outclassed by the great Eurasian-African landmass in terms of territory, economic resources, and population. To maintain access to resources and friends, Americans must have bases abroad, air power, and, above all, the mobility and power of a superior three-ocean navy."

Cline also served as Vice President of the Veterans of the Office of Strategic Services and was the founder and president of the National Intelligence Study Center and president of the Committee for a Free China.

Ray S. Cline died on 15 March, 1996 in Arlington, Virginia.

Primary Sources

(1) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

In the prewar and early war period in Roosevelt's Washington, agencies were proliferating wildly in response to an awareness that the nation was appallingly unprepared for the challenges ahead. It was easy enough for Roosevelt to provide a charter and authorize Donovan to start an agency and spend several millions of largely unvouchered dollars.' Still, it was not easy for Donovan to acquire the staff he needed, find office space for them, get them paid either as civil or military personnel, and impart some sense of specific duties to his fledgling outfit. Army and Navy intelligence, the FBI, and the State Department inevitably resisted what they viewed as encroachment on their domains, and the Bureau of the Budget watchdogs were reluctant to release funds under the rather vague description of duties in the Donovan charter.

"Wild Bill" deserves his sobriquet mainly for two reasons. First, he permitted the "wildest," loosest kind of administrative and procedural chaos to develop while he concentrated on recruiting talent wherever he could find it - in universities, businesses, law firms, in the armed services, at Georgetown cocktail parties, in fact, anywhere he happened to meet or hear about bright and eager men and women who wanted to help. His immediate lieutenants and their assistants were all at work on the same task, and it was a long time before any systematic method of structuring the polyglot staff complement was worked out. Donovan really did not care. He counted on some able young men from his law firm in New York to straighten out the worst administrative messes, arguing that the record would justify his agency if it was good and excuse all waste and confusion. If the agency was a failure, the United States would probably lose the war and the bookkeeping would not matter. In this approach he was probably right.

In any case, Donovan did manage during the war to create a legend about his work and that of OSS that conveyed overtones of glamour, innovation, and daring. This infuriated the regular bureaucrats but created a cult of romanticism about intelligence that persisted and helped win popular support for continuation of an intelligence organization. It also, of course, created the myths about intelligence-the cloak-and-dagger exploits-that have made it so hard to persuade the aficionados of spy fiction that the heart of intelligence work consists of properly evaluated information from all sources, however collected.

The second way in which Donovan deserved the term "Wild' was his own personal fascination with bravery and derring-do. He empathized most with the men behind enemy lines. He was constantly traveling to faraway theaters of war to be as near them as possible, and he left to his subordinates the more humdrum business of processing secret intelligence reports in Washington and preparing analytical studies for the President or the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS).

Fortunately Donovan had good sense about choosing subordinates. Some were undoubtedly freaks, but the quotient of talent was high and for the most part it rose to the top of the agency. One of Donovan's greatest achievements was setting in motion a train of events that drew to him and to intelligence work a host of able men and women who imparted to intellectual life in the foreign field some of the verve and drive that New Deal lawyers and political scientists had given to domestic affairs under Roosevelt in the 1930s.

Thomas G. (Tommy) Corcoran, Washington's durable political lawyer and an early New Deal "brain-truster" from Harvard Law School, says that his greatest contribution to government in his long career was helping infiltrate smart young Harvard Law School products into every agency of government. He felt the United States needed to develop a highly educated, highly motivated public service corps that had not existed before Roosevelt's time. Donovan did much the same for career experts in international affairs by collecting in one place a galaxy of experience and ability the likes of which even the State Department had never seen. Many of these later drifted away, but a core remained to create a tradition and eventually to take key jobs in a mature intelligence system of the kind the United States required for coping with twentieth century problems.

(2) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

The action staff in OSS, especially those in the overseas stations, benefited enormously from being celebrated in prose written by skillful and successful writers. The mythical aspects of CIA took wings almost immediately after the end of the war when two able journalists, Corey Ford and Alistair MacBain, were given permission by Donovan to write a breezy suspense story called Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of OSS. It came out in 1945 with a"tribute" by General Donovan, printed as foreword, that began: "Now that the war is ended it is only fair to the men of OSS, who have taken some of the gravest risks of the war, that their courage and devotion should be made known." In 1946 a slightly more substantial book by two first-class writers who had served in OSS, Stewart Alsop and Tom Braden, was written under the title Sub Rosa: The OSS and American Espionage. Alsop and Braden had parachuted into France as JEDBURGH team members; they described the bravery and excitement of the OSS operational missions in stories that still read well and provide a good bit of the substance for later, more systematic books on OSS operations. The literature of OSS revealed some of the frantic improvisation of OSS espionage and covert operations, but it invariably left an overwhelming impression of daring, unconventionality, and heroic achievement. While Alsop, at least, knew enough from his friends in R&A to include some indication of the central intelligence analysis function of OSS, this part of the story seems inevitably humdrum in comparison to the derring-do.

The story of the research and analysis functions of OSS might not have survived at all if it had not been written about by the thoughtful historian, Sherman Kent. Kent stayed on in Washington for a short time after R&A was transferred to the State Department, before he returned to Yale. (He came back to Washington a number of years later to serve for 20 years in CIA's Office of National Estimates.) His book of this period, Strategic Intelligence For American World Policy, finished in October 1948, provided a generation of intelligence officers with a rational model for their profession of collecting and analyzing information.14 By the time the book came out the fledgling CIA was in existence and Kent uses terms that suggest he is describing the new organization. Actually he is reflecting on his experience in OSS's R&A Branch and outlining an idealistic concept of the hard work of the intelligence analyst.

Since it does not really tell what went on in either OSS or CIA, Kent's book is an abstract treatment of a concept that had been articulated but never realized. Kent told me at the time that he had a hard time finding a publisher. There was no broad commercial success for Strategic Intelligence as compared with Cloak and Dagger or Sub Rosa. Nevertheless, the essence of the intelligence process had been captured on paper. As Kent put it, intelligence is "the kind of knowledge our state must possess regarding other states in order to assure itself that its cause will not suffer nor its undertakings fail because its statesmen and soldiers plan and act in ignorance. This is the knowledge upon which we base our high-level national policy toward the other states of the world."Furthermore, Kent observed what is to this day difficult to persuade people about, "some of this knowledge may be acquired through clandestine means, but the bulk of it must be had through unromantic open-and-above-board observation and research." These truths, too, were part of the legacy of OSS, although they were nearly buried under the legends of cloaks and daggers and paramilitary operations.

(3) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

The one thing that Army, Navy, State, and the FBI agreed on was that they did not want a strong central agency controlling their collection programs. Admiral Ernest J. King, an efficient but narrowly partisan military man, voiced a fear that has always been present; King told Navy Secretary Forrestal he "questioned whether such an agency could be considered consistent with our ideas of government." Truman himself repeatedly said, more with reference to the FBI, that "this country wanted no Gestapo under any guise or for any reason." These expressions of doubt are legitimate concerns, but they all served as bars to necessary centralization of intelligence tasks. The fact is that it is possible to introduce checks and balances that render central intelligence accountable to our constitutional government; it is not possible for the government to cope with the problems that beset it abroad without an efficient, coordinated central intelligence system.

(4) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

The second great man Smith brought back to the intelligence profession was Allen Dulles. Although in private law practice, Dulles had kept his Washington connections alive and was often called on for informal as well as formal advice on intelligence issues. He had participated with William H. Jackson and Matthias F. Correa in an NSC study during 1948 that lambasted CIA as then constituted for failure to draft authoritative national estimates and failure to coordinate intelligence activities of other agencies. Much of the same kind of criticism was incorporated in the Hoover Commission study of the CIA in early 1949 and in an NSC study (NSC 50) of July 1949, so Smith turned to Dulles and Jackson to carry out the recommendations. Jackson became general administrative officer for the reorganization, with the title of Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, and served 10 months in this capacity.

Dulles also accepted Smith's bid but found to his dismay that Smith was unwilling to proceed at once with the integration of OSO and OPC, the clandestine collection and covert action offices, as the Dulles, Jackson, Correa report had recommended. Dulles nonetheless took on the arduous task of reducing the clandestine and covert activities to some semblance of order, accepting an assignment on January 2, 1951 as a Deputy Director responsible for both OPC and OSO. While Smith and Dulles never really hit it off too well personally, they respected each other's skills. Dulles stayed on duty in CIA for 10 tumultuous years, moving up to replace Jackson as Deputy Director after Jackson left. In due course, when Eisenhower took office as President in 1953 and Allen's older brother, Foster, became Secretary of State, he became the first professional intelligence officer to be Director of Central Intelligence. No other man left such a mark on the Agency.

One managerial problem of consequence was solved immediately by Smith. As soon as he took office he simply stated that he would take over the administrative responsibility for and control over OPC covert action operations. Thus Defense and State would exert policy guidance through the DCI rather than deal directly with Frank Wisner, the OPC Chief. The new arrangement was accepted formally by State, Defense, and the Joint Chiefs on October 12, 1950. Smith delegated some of the job of coordinating OPC and OSO operations to Dulles, whom he designated as Deputy Director for Plans in January 1951. Thus Smith brought covert action into a clean line-of-command position in the Agency and, through Dulles, kept an eye on these units' activities. By 1952 Smith accepted the logic of Dulles' position on the awkwardness and frequent embarrassment of having separate OPC and OSO units doing secret work in the same place at the same time, competing for resources and personnel. In August 1952 he formally set up what came to be called the Directorate of Plans, usually referred to as the DDP, in which the two were combined.

Gradually the two offices, OPC and OSO, began to coordinate activities at least to the point of not competing for the services of the same agents by offering higher wages and better privileges. In time some individuals in the field began to perform dual functions, collecting information and maintaining covert political relations and often using the same sources for both purposes. The merger did not really become effective across the board until Dulles became DCI, but in its Directorate of Plans CIA already, by the end of the Smith reform era, had consolidated the clandestine and covert functional tasks sufficiently for the generic term "clandestine services" to come into use to describe the two operational elements of the agency assigned to duty under the DDP. When in August 1952 the old OSO and OPC merged into a complex semi-geographical, semi functional structure, the intelligence collectors retained, psychologically and bureaucratically, a separate identity from the operators-the covert action specialists.

The general character of the initial merger was reflected in the fact that the Deputy Director for Plans was Frank Wisner of OPC, while his second in command, with a newly created title of Chief of Operations (COPS), was Richard Helms of OSO. Over time the lines gradually blurred as the supervisory echelons of the clandestine services were required to handle both espionage and covert action cases.

(5) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

During my London tour I also discovered something of the character of the psychological and political warfare thinking going on in CIA. Two men I knew well were in London for OPC, then still rather separate from the old-line OSO forces under the station chief. These men had a separate status in the U.S. Embassy very similar to my own. We were under the general supervision of Betts, we had diplomatic passports, and we generally kept some distance from the larger contingent involved in exchange of espionage and counterespionage reports. This was easy, since the station chief and his deputy had their bailiwick down the street in a separate building, as did the U.S. military personnel who, in still another building, maintained the very close U.S.-U.K. liaison in the signals field under only the most general cognizance of General Betts. At any rate I discovered some interesting things from my friends.

In addition to channeling funds and information to nonCommunist political parties, newspapers, labor unions, church groups, and writers throughout Western Europe, Frank Wisner's OPC had undertaken to see that accurate news and political analysis reached not only Western Europe but Eastern Europe, where populations under the Soviet thumb were yearning for greater freedom. The instrument used to keep alive some knowledge of what was going on in open societies was Radio Free Europe. It was formed by CIA, which ran it and its companion broadcasting service, Radio Liberty-which reported news for the benefit of Soviet listeners in the USSR itself-for 20 years. Staffed primarily by refugees from the countries to which programs were beamed, these radios have been able to get hard news into the regions behind the iron curtain, bringing subtle psychological pressures to bear on dictatorial governments to temper their control methods. CIA organized this effort at the request of U.S. Government officials because it was thought the broadcasts would be more effective if their connection with the U.S. Government could be concealed.

Although it is hard to measure the influence of psychological weapons like Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, they both certainly won many regular listeners. The leaders of the Soviet Union have clearly feared the impact of ideas from outside on their society; they have spent millions and millions to jam these broadcasts, pausing only intermittently in brief periods of "peaceful coexistence" and then resuming the jamming. At their peak, these radio broadcast efforts cost about $30 million a year and employed several thousand uniquely qualified analysts and linguists. The effort was so clearly aimed at freedom of information and amelioration of Communist restraints on civil liberties that the U.S. Congress finally, in 1973, established a public board to manage these instruments of political action. CIA gladly shed its responsibility since the operations had become too large and had operated too long to be genuinely covert. The transfer from covert to overt U.S. sponsorship sets a pattern for what ought to happen to CIA projects when they become too well known to be secret but are still useful supports for U.S. policy. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty are public evidence of CIA covert action projects that were successful, served liberal democratic purposes, and never became the center of controversy as so many paramilitary projects did.

It was exciting to see the early evolution of covert action and psychological warfare activities in Europe in the early 1950s. Many other lesser projects were funded and pursued, many of them quite small-scale. Many international labor and youth movements benefited by having CIA help non-Communist members oppose heavy-handed Communist efforts to seize control of all organs of mass opinion. Europeans made the major effort, but CIA support with money and information about Communist activities played a crucial part in preserving the multi-party political systems of Western Europe.

In my view, CIA especially deserves credit for encouraging left-wing intellectuals to find a democratic alternative in nonCommunist organizations and enterprises. The Congress of Cultural Freedom, a genuine liberal intellectual movement in Europe, would never have got going without CIA help, and a number of first-class magazines of political commentary, such as Encounter and Monat, would not have been able to survive financially without CIA funds.

(6) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

In the early 1950s two major covert action projects were undertaken, with enthusiastic support from State and everyone else, in which political action merged into paramilitary action, blurring the distinction, much to the subsequent disadvantage of CIA. In 1953, while I was still in London, a covert operation so successful that it became widely known all over the world was carried out in Iran. The Shah, then very young, had been driven out of Iran by his left-leaning Premier, Mohammed Mossadegh, whose support came from the local Communist (Tudeh) Party and from the Soviet Union. CIA mounted a modest effort under a skillful clandestine services officer who flew into Iran, hired enough street demonstrators to intimidate those working for Mossadegh, instructed Iranian military men loyal to the Shah how to take over the local radio station, and paved the way for the Shah's triumphal return.

The trouble with this seemingly brilliant success was, as the officer in charge would testify, that CIA did not have to do very much to topple Mossadegh, who was an eccentric and weak political figure. It took relatively little effort to restore the traditional ruler to his throne once he and his military supporters recovered their nerve and took advantage of U.S. help. It did not prove that CIA could topple governments and place rulers in power; it was a unique case of supplying just the right bit of marginal assistance in the right way at the right time. Such is the nature of covert political action. Regrettably, romantic gossip about the "coup" in Iran spread around Washington like wildfire. Allen Dulles basked in the glory of the exploit without ever confirming or denying the extravagant impression of CIA's power that it created.

About a year later, in mid-1954, the legend of CIA's invincibility was confirmed in the minds of many by a covert action project in Guatemala that inched one step farther toward paramilitary intervention. President Arbenz Guzman had expropriated the holdings of the powerful U.S.-owned United Fruit Company and was discovered by CIA to be about to receive a boatload of Czechoslovakian arms. This fact, publicized by the State Department on May 17, touched off a six-week crisis in which a rival Guatemalan political leader, Castillo Armas, launched a desultory invasion of Guatemala supported by three P-47 fighter planes of World War II vintage flying from friendly Nicaraguan territory. The aircraft were provided by CIA and flown by soldier-of-fortune pilots recruited by CIA. The U.S. Ambassador, John E. Peurifoy, was in charge of the operation and President Eisenhower had personally approved it on assurance from Allen Dulles that it would succeed in getting rid of a left-leaning dictator within the precincts of what was still considered a viable Monroe Doctrine. There was not much fighting, but the P-47s created a lot of excitement, and support for Arbenz Guzman crumbled. A junta took over, made an accommodation with Castillo Armas, and he became president in early July.

(7) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

One of my biggest headaches in Taiwan was keeping a weather. eye on the main component of CIA's first established proprietary companies-the headquarters of the interlocking set of aviation enterprises that included Air America, Civil Air Transport (CAT), and Air Asia. The companies were built around the fleet of C-46 and C-47 cargo aircraft that were flown to Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalists. The fleet was gradually taken over financially by CIA to keep the pilots and aircraft available for clandestine or covert missions when these were needed. A fleet of DC-4s and DC-6s, the best transport aircraft of the pre-jet age, was gradually acquired, and eventually there were some Boeing 727s and one Convair 880.

One of the main tasks of the fleet was dropping supplies to the large Chinese Nationalist armies that fought on against the Communists in southwest China for a number of years before settling down semi-permanently in the wild China-Burma-Thailand border area. There some of them remain even now despite the discontinuation of U.S. support many years ago and the air evacuation of those willing to leave their jungle stronghold and settle down in Taiwan.

The CAT-Air America pilots and crews were true soldiers of fortune and accepted enormous risks on long, clandestine missions over hostile territory, such as flying missions under fire to make parachute drops at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam for the French. These CIA-supported aviation companies had such a quantity of experienced ground and flight personnel that the U.S. Air Force eagerly contracted with them for transport services throughout the Far East.

Most valuable among the air proprietary assets in Taiwan was a maintenance and repair shop, originally housed in an old navy landing craft brought over from mainland China in 1949. With its well-trained Chinese repair crews it provided the best maintenance service anywhere in the Far East and was a regular money-maker, especially when hostilities in Vietnam picked up in the 1960s. These earnings were mainly used to offset losses in other categories of air activities. Whenever net profits accrued for the whole complex, the money was pumped back into the U.S. Air Force (in lieu of contract renegotiations) or to the U.S. Treasury.

This vast endeavor was so large that it had to be run from Headquarters, mainly under the eye of Larry Houston, CIA's General Counsel. The local station chief was mainly useful as a channel for secret instructions to employees of the companies. I also occasionally had to intervene quietly to smooth out personnel employment policy problems, tax difficulties, and relations with various Chinese organizations that did not know about the U.S. connection. Eventually the Republic of China established its own passenger airline and this whole net was phased out-although it took the end of the Vietnam war in 1975 to bring about the last stage of the liquidation.

(8) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

A great deal of documentation has been made public recently on CIA operations against Fidel Castro's Cuba, as well as much testimony, often conflicting, by senior U.S. officials concerning efforts to get rid of Castro.3 For this reason I intend to discuss only the highlights and the basic meaning of this first great disaster to befall CIA at the end of the Allen Dulles era. I was stationed in the Far East at the time and, happily, was not. involved with it. Still, I was aware of the broad outlines of what was going on and have learned a great deal more after the event.

In a sense, the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961 represented the logical culmination of the trend toward increasing U.S. reliance on paramilitary operations conducted covertly by CIA on the theory that the United States could plausibly deny responsibility for this kind of secret support to U.S. policy. The record is clear that both Eisenhower and Kennedy found the idea of a Soviet-oriented Communist dictatorship close to U.S. territory extremely repugnant. After due deliberation, the Eisenhower administration in 1960 set up a CIA-run program for training hundreds of highly motivated anti-Castro Cuban refugees in guerrilla warfare. Vice President Nixon was a strong proponent of an active program to topple the Castro regime and Eisenhower, upon the advice of the NSC subcommittee responsible for reviewing covert action schemes, approved the Cuban paramilitary training project as a contingency plan-leaving its execution to be decided upon early in the new administration.

CIA had advocated the "elimination of Fidel Castro" as early as December 1959, and the matter was discussed at Special Group meetings in January and March of 1960. At an NSC meeting on March 10, 1960 terminology was used suggesting that the assassination of Castro, his brother Raul, and Che Guevara was at least theoretically considered.4 The idea of guerrilla operations was abandoned in November 1960. The anti-Castro Cubans were in fact organized into a Brigade that went into intensive preparations for an invasion by about 1,400 armed men in the Bay of Pigs landing area on Cuba's southwest coast. Allen Dulles endorsed the project repeatedly and the JCS concurred in it.

The project was the exclusive property of the DDP, with an assist from the Support Directorate, specifically from the Security Office Chief. Bob Amory, the DDI, was never officially consulted about the pros and cons of the Bay of Pigs landing and all estimates of probable success of the project were made by the DDP operators themselves, a remarkably unsound procedure. Dick Bissell, the DDP, and his covert action chief assistant Tracy Barnes, managed the project in Washington and issued detailed orders to the field echelons. The instructions to move against Castro were so explicit and the general atmosphere of urgency was so palpable that two very responsible officers, Bissell and longtime Chief of Security Sheffield Edwards, thought they had been authorized to plan Castro's assassination. Although it was an unprecedented act for CIA, once the assumption was made that it was essential to get rid of Castro by assassination, it was not illogical to try to do it through the Mafia, since its former Havana gambling empire gave them some contacts to work with and since a gangland killing would be unlikely to be attributed to the U.S. Government. Whether President Eisenhower or Dulles or President Kennedy had actually intended to authorize Castro's murder is simply not clear from the records. I did not know anything about this assassination planning, although I clearly recall the animus against Castro manifested in every discussion of Cuba in this period at every level of government.

CIA's becoming engaged in planning assassinations was not a momentary aberration on the part of the handful of men who were involved. In January 1961, when preparations for the Cuban Brigade were at a peak, Bissell ordered William Harvey, a veteran station chief, to set up a "standby capability" for what was called euphemistically "Executive Action," by which was plainly meant a capability for assassination of foreign leaders as a "last resort." Harvey was a colorful figure, a former FBI man who carried a pistol at all times when posted abroad, something unique among CIA officers. I am sure he believed that it was patriotic, even moral, to kill a foreign ruler when ordered to do so by his superiors for reasons of U.S. security. Many of the romantic so-called "cowboy" types of covert action officers would have accepted this proposition, and in 1960-1961 many officials outside CIA would have subscribed to it as well. In any event, the responsible officers in CIA, Harvey and Bissell, were convinced at the time that the White House had orally urged the creation of an assassination planning capability as a contingency precaution. The written record does not clearly demonstrate this to be either true or untrue.

(9) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

That system received a severe buffeting when Nixon summarily transferred Helms out of CIA after the election of 1972. In 1971 a relatively unknown economist in the Bureau of the Budget, James Schlesinger, made a very sensible study of central intelligence. For his pains he was made Director of Central Intelligence to try to carry out his own suggestions; he stayed in this job only from February to July 1973, when he was abruptly transferred to Defense. He made three important moves in this brief period-all wrong. All were designed to tighten White House control of CIA as a secret instrument of operational utility. One was to abolish the Office of National Estimates, a move not effected until after his departure, but one decided upon very early by Kissinger and Schlesinger; the second was to retire summarily over 2,000 employees, most of them the oldest hands at CIA, an act that brought morale to a new low; the third was to subordinate to the clandestine services CIA's long-established overt collection system responsible for contacting U.S. citizens who wanted to pass to the government information learned abroad. The deinstitutionalization of the national estimates system, which thenceforth had as its main purpose writing estimates to order for the NSC staff, the abrupt dismissal of so many CIA officers, making it look as if something had been very wrong, and the reinforcement of the cloak-and-dagger image in connection with perfectly overt CIA functions in the United States-all these were retrograde steps for which CIA has suffered since.

The job of DCI was then passed along to Bill Colby, the able clandestine services officer who had returned from Vietnam to be Executive Director of CIA under Helms. This move probably accounts for the survival of CIA as an institution despite the blows it has received. Bill is a courageous, broadminded intelligence officer, a man of total integrity and dedication to the public service. It was a handicap for him to be tagged as a covert action operator of many years and a prominent activist in Vietnam just when CIA came under fire for its covert acts, but he handled himself with great responsibility and professional dignity in a very tough situation. The end of the Nixon era was a bad period for the whole federal bureaucracy; for Bill Colby, the end of the Watergate episode when the President left office in August 1974 was followed by a wave of press and Congressional criticism that occupied him fully until the end of 1975.

(10) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

Then, it was revealed, Nixon had pressured Helms and his principal Deputy, General Vernon Walters, to have CIA call the FBI off the track of the laundered money paid to the Watergate burglars. After a few days of ambiguity, CIA decisively indicated that CIA operations provided no grounds for diverting the FBI from the Watergate investigation. This unwillingness to cooperate in the White House cover-up may be what cost Dick Helms his job five months later, after the 1972 election. Nevertheless, the episode raised suspicions-never confirmed-that CIA had more to do with Watergate than had been surfaced.

In this atmosphere, attacking CIA for a variety of reasons became more plausible for critics and profitable for journalists! At this point, in 1973 and 1974, the Senate and House Intelligence Subcommittees began to take closer notice of CIA ' covert action, particularly in Chile, which was then under i inquiry by separate Senate and House foreign relations subcommittees dealing with multinational corporations and inter-American affairs. It is now absolutely clear the CIA's covert action program in Chile in the 1970s was undertaken under express orders from President Nixon and his National Security Assistant, Dr. Kissinger. In fact, both CIA and State were reluctant to become so deeply involved in what appeared to be an unfeasible program to keep President Salvador Allende out of office after he had won a plurality in the September 1970 election. At one point, the President and Dr. Kissinger even took matters out of the hands of the 40 Committee of the NSC and directed CIA, much against its officers' judgment, to try to stage a military coup, a project which never came to anything. CIA continued to provide large sums of money, evidently around $8 million, to support parliamentary opposition to the increasingly arbitrary and socially disruptive rule of Allende - especially to keep alive an opposition press.

(11) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

After a decent interval, to all appearances without vindictive feelings toward either Dulles or Bissell, Kennedy set out to restructure the high command at CIA. For a brief period during 1962 and 1963 CIA operated at its peak performance level in the way that its functional responsibilities called for, with greater emphasis on intelligence analysis and estimates and an attempt at greater circumspection and tighter control in covert action. The key to success was Kennedy's appointment of a new Director of Central Intelligence, John A. McCone, in November 1961. It was a bold move by Kennedy to pick McCone, an active Republican and a businessman turned government administrator, rather than someone with experience in intelligence. It turned out well.

CIA needed a man with personal political stature to represent it at the highest levels in the White House and in Congress, especially in the dark days after the Bay of Pig. McCone was an engineer who had made a fortune in construction and shipbuilding enterprises. He was well acquainted in private industry and, in addition, had earned respect as a public servant by working first as Under Secretary of the Air Force and later as Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. He had great energy and - above all - the inquiring, skeptical turn of mind of the good intelligence officer. He is the only DCI who ever took his role of providing substantive intelligence analysis and estimates to the President as his first priority job, and the only one who considered his duties as coordinating supervisor of the whole intelligence community to be a more important responsibility than CIA's own clandestine and covert programs. Kennedy gave him a letter of instructions on January 16, 1962 designating him as the "government's principal foreign intelligence officer" with a charge to "assure the proper coordination, correlation, and evaluation of intelligence from all sources and its prompt dissemination. . . ." It also tasked him with "coordination and effective guidance of the total U.S. foreign intelligence effort."

McCone tried to live up to this heavy responsibility and came closer to discharging it than anyone else. He hated being called a "spymaster," as he often was in press comments echoing the Dulles tradition. In collection efforts he took primary interest in the technical programs, especially the rapidly expanding satellite photo systems. Covert actions were small in scale and quietly carried out in this period and agent collection was recognized as a useful but intricate job best left to Dick Helms and his professional staff, provided they could answer McCone's occasional barrage of questions.

(12) Group Watch: World Anti-Communist League (October, 1990)

The World Anti-Communist League was founded in 1966 in Taipei, Taiwan. WACL was conceived as an expansion of the Asian People's Anti-Communist League, a regional alliance against communism formed at the request of Chiang Kai-shek at the end of the Korean War. The Asian People's AntiCommunist League (APACL) had roots in the China Lobby, a group dedicated to stopping official international recognition of the Chinese Communist government. The China Lobby had U.S. government connections, and allegedly Ray Cline of the CIA assisted this group in establishing the Taiwanese Political Warfare Cadres Academy in the late 1950s. The founders of APACL were agents of the governments of Taiwan and Korea, including Park Chung Hee who later became president of Korea; Yoshio Kodama, a member of organized crime in Japan; Ryiochi Sasakawa, a gangster and Japanese billionaire jailed as a war criminal after World War II; and Osami Kuboki and other followers of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, head of the Unification Church. Sasakawa provided major funding for Moon and the Unification Church. When Park became president of South Korea after the 1961 coup, he adopted the Unification Church as his political arm....

United States: The first WACL chapter in the U.S. was the American Council for World Freedom (ACWF) founded in 1970 by Lee Edwards. Edwards was the former director of Young Americans for Freedom, the youth arm of the John Birch Society. John Fisher of the American Security Council served as ACWF's first chairman. The American Security Council is a virulently anticommunist group that originally focused on internal security. It currently heads up the right wing lobby group the Coalition for Peace Through Strength, which includes among its members a number of members of Congress. (61) In 1973, the ACWF, at the urging of board member Stefan Possony, complained to WACL about the fascist members from Latin America. The report was discredited, but in 1975, ACWF left WACL and its members drifted off to other groups in the New Right.

The second U.S. chapter of WACL (1975-1980), the Council on American Affairs, was headed by noted racialist Roger Pearson. During this period Pearson had strong links to the American Security Council.

In 1980 John Singlaub went to Australia to speak to the Asian branch of WACL. Shortly thereafter he was approached to begin a new U.S. chapter of the organization. The U.S. Council for World Freedom (USCWF) was started by the retired General in 1981 with a loan from WACL in Taiwan and local funding from beer magnate, Joseph Coors. USCWF has been the most active chapter of WACL of this decade, with the action picking up tremendously in 1984 with the cessation of official U.S. government funding to the contras. Singlaub was selected by the White House in 1984 to be the chief private fundraiser for the contras. The key private funders were to be wealthy business people, Taiwan, South Korea, and "an anti-communist organization with close ties to those governments." Other major contributions came from Guatemala and Argentina, countries where Singlaub had strong WACL connections. In his position as chief private fundraiser for the contras Singlaub reported directly to Colonel Oliver North of the National Security Council. It is highly likely that Singlaub's USCWF/WACL high-profile,"private" contra fundraising may have served as a cover for North's illegal government-sponsored supply network.

In his deposition at the Iran-Contra hearings, Singlaub's claims that he raised $10 million in contra aid were questioned. In 1985, for example, when claims of millions of dollars in aid raised from private sources were reported frequently by the media, the USWCF financial statement reported income of $280,798. In the previous year, reported income was just over $41,000. Singlaub responded that a good deal of the aid was "in-kind" and that the dollar values were somewhat uncertain. He also claimed that his statements had been exaggerated by the press.

What Singlaub has done as a private citizen and what he has done in the name of USCWF and WACL is unclear. However, WACL paid for the services of the public relations firm of Carter Clews Communications to improve Singlaub's public image in order to enhance his fundraising efforts.

The USCWF and Soldier of Fortune established a private training academy for Salvadoran police forces and Nicaraguan contras. Located in Boulder, Colorado, the Institute for Regional and International Studies was headed by Alexander McColl, the military affairs editor of Soldier of Fortune Magazine. Robert Brown of Soldier of Fortune invested $500,000 in Freedom Marine. In December 1985 Freedom Marine sold three "stealth boats" to USCWF for $125,000. The hulls of the boats had been reinforced for machine gun mounts. In Honduras the coastal resupply system for rebels inside Nicaragua utilized three "stealth boats." Bruce Jones, former CIA liaison to the contras in Costa Rica, worked for USCWF in Tucson.

In 1987, USCWF lost its tax-exempt status because of complaints about the group's support of the Nicaraguan contras and is reported to be short of money. USCWF apparently moved its offices from Phoenix to Alexandria, Virginia in 1988. Singlaub was indicted in 1986 and 1988 over USCWF activities in support of the contras. Because of these costly legal problems USCWF has been politically inactive and NARWACL did not hold its annual meeting in 1988-1989.

David Finzer and Rafael Flores founded the World Youth Freedom League (WYFL), the youth branch of WACL in 1985. Flores, worked for contra fundraiser, Carl (Spitz) Channell, also indicted in the Iran-contra case. Finzer and Flores worked together at the International Youth Year Commission, a group linked to Oliver North's contra supply network.