Tommy Corcoran

Thomas Corcoran, the son of a lawyer, was born in Rhode Island on 29th December, 1899. He was educated at Brown University and Harvard Law School. Corcoran's most important influence at university was Professor Felix Frankfurter. He wrote that Corcoran was "struggling very hard with the burden of inferiority imposed on him because of his Irish Catholicism". Frankfurter was impressed with Corcoran's progress and introduced him to his close friend, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. After graduating in 1926 he was invited by Holmes to become his legal clerk.

In 1927 Corcoran joined the law firm established by William McAdoo. At the time it was run by George Franklin and Joseph Cotton. In 1932 Eugene Meyer, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, was looking for a general counsel for the newly established Reconstruction Finance Corporation. After talks with Franklin he appointed Corcoran to this post. Meyer resigned in 1933 and was replaced by Jesse H. Jones.

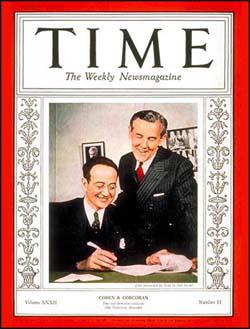

After Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover he asked Felix Frankfurter to assemble a legal team to review the nation's securities laws. Frankfurter selected Corcoran, Benjamin Cohen and James Landis for the task. Corcoran, a member of the Democratic Party, readily accepted the post. Together they drafted the legislation that created the Securities and Exchange Commission.

William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "Corcoran was a new political type: the expert who not only drafted legislation but maneuvered it through the treacherous corridors of Capitol Hill." Ray S. Cline added: "Corcoran... says that his greatest contribution to government in his long career was helping infiltrate smart young Harvard Law School products into every agency of government. He felt the United States needed to develop a highly educated, highly motivated public service corps that had not existed before Roosevelt's time."

The following year Corcoran was involved in drafting the Public Utilities Holding Company Act. On 1st July, 1935, Owen Brewster claimed that Corcoran threatened to stop construction on the Passamaquoddy Dam in his district unless he supported the Holding Company Bill. Congress immediately ordered the rules committee to investigate the matter. The Senate investigation, headed by Hugo Black, eventually cleared Corcoran of any wrongdoing. Corcoran wrote to a friend: "Storms make a sailor - if he survives them."

Roosevelt's personal secretary, Louis M. Howe, died of pneumonia on 24th June, 1936. According to Corcoran's biographer, David McKean (Peddling Influence), Corcoran now replaced Howe as Roosevelt's most "trusted adviser and personal companion". Some of Roosevelt's ministers complained about Corcoran's growing influence. Henry Morgenthau, the Secretary of the Treasury, claimed that Corcoran was a "crook". As well as drafting New Deal legislation, Roosevelt used Corcoran as his "special emissary to Capitol Hill". Elliott Roosevelt wrote that: "Apart from my father, Tom (Corcoran) was the single most influential individual in the country."

In 1937 Corcoran used this influence to make sure Sam Rayburn of Texas became Speaker of the House. This was a difficult task as James Farley was advocating that John O'Connor got the job. Corcoran's increasing power was indicated by the fact that Franklin D. Roosevelt brought an end to Farley's campaign. This was the beginning of a very close relationship that Corcoran enjoyed with Rayburn and the Texas oil industry.

Franklin D. Roosevelt began to have considerable problems with the Supreme Court. The chief justice, Charles Hughes, had been the Republican Party presidential candidate in 1916. Hughes, appointed by Herbert Hoover in 1930, led the court's opposition to some of the proposed New Deal legislation. This included the ruling against the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) and ten other New Deal laws.

On 2nd February, 1937, Franklin D. Roosevelt made a speech attacking the Supreme Court for its actions over New Deal legislation. He pointed out that seven of the nine judges (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, George Sutherland, Harlan Stone, Owen Roberts, Benjamin Cardozo and Pierce Butler) had been appointed by Republican presidents. Roosevelt had just won re-election by 10,000,000 votes and resented the fact that the justices could veto legislation that clearly had the support of the vast majority of the public.

Roosevelt suggested that the age was a major problem as six of the judges were over 70 (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, James McReynolds, Louis Brandeis, George Sutherland and Pierce Butler). Roosevelt announced that he was going to ask Congress to pass a bill enabling the president to expand the Supreme Court by adding one new judge, up to a maximum off six, for every current judge over the age of 70. Hughes realized that Roosevelt's Court Reorganization Bill would result in the court coming under the control of the Democratic Party. Behind the scenes Hughes was busy doing deals to make sure that Roosevelt's bill would be defeated in Congress.

Tommy Corcoran was giving the task by Roosevelt to persuade Congress to pass this proposed legislation. This included working closely with I. F. Stone of the New York Post. Stone, a strong opponent of the conservative Supreme Court, agreed to write speeches for Corcoran on this issue. These speeches were then passed on to Roosevelt supporters in Congress.

In the past Corcoran had relied heavily on the influence of his close friend, Burton Wheeler, chairman of the Judiciary Committee. However, Wheeler had now turned against Roosevelt. Wheeler even argued that Franklin D. Roosevelt had been behind the assassination of Huey Long. Corcoran continued to campaign for the Judicial Court Reorganization Bill but he failed to persuade enough to get it passed.

Even the most left-wing of all the justices, Louis Brandeis, opposed Roosevelt's attempt to "pack" the Supreme Court. Brandeis was also beginning to oppose some aspects of the New Deal that he believed "favored big business". However, members of the Supreme Court accepted they had to fall in line with public opinion. On 29th March, Owen Roberts announced that he had changed his mind about voting against minimum wage legislation. Hughes also reversed his opinion on the Social Security Act and the National Labour Relations Act (NLRA) and by a 5-4 vote they were now declared to be constitutional.

Then Willis Van Devanter, probably the most conservative of the justices, announced his intention to resign. He was replaced by Hugo Black, a member of the Democratic Party and a strong supporter of the New Deal. In July, 1937, Congress defeated the Court Reorganization Bill by 70-20. However, Roosevelt had the satisfaction of knowing he had a Supreme Court that was now less likely to block his legislation.

Corcoran later took credit for getting Hugo Black (1937), Felix Frankfurter (1939), William O. Douglas (1939) and Frank Murphy (1940) appointed to Supreme Court. He also played an important role in defending Black when it was discovered that he was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan. Corcoran later claimed he wrote Black's statement asking for forgiveness.

Corcoran also became involved in advising Franklin D. Roosevelt over foreign policy. Although he had liberal views on domestic issues, Corcoran was passionately anti-communist. This was partly because of his Roman Catholicism. Roosevelt initially favoured giving help to the Republican government in Spain. However, Corcoran was a supporter of the fascist movement led by General Francisco Franco.

As Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson pointed out in their book, The Case Against Congress: A Compelling Indictment of Corruption on Capitol Hill: “Long before Pope John and Pope Paul made it clear they were not in sympathy with the Catholic hierarchy of Spain, the reactionary wing of the Catholic Church in the United States had been conducting one of the most efficient lobbies ever to operate on Capital Hill. It was able to reverse completely American policy on Spain. During the Spanish Civil War, Thomas G. Corcoran, a member of the Roosevelt brain trust, worked effectively at the White House to keep an embargo on all U.S. arms to both sides.”

Corcoran knew that Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini would continue to provide both men and arms to Francisco Franco. Roosevelt's decision enabled fascism to win in Spain and become entrenched in Europe. Roosevelt later told his cabinet that he had made a "grave mistake" with respect to neutrality in the Spanish Civil War. Roosevelt was angry with Tommy Corcoran over his advice on Spain. He also began to see that Corcoran was becoming a problem for the administration. He had upset a lot of powerful figures in Congress with his arm twisting tactics. Corcoran had also tried to unseat those who attempted to resist Franklin D. Roosevelt. For example, Walter George of Georgia claimed that Corcoran had the "power of saying who shall be a senator and who shall not be a senator."

In June 1939, an article appeared in the Saturday Evening Post accused James Roosevelt of being a war profiteer. It was also claimed that the president's son helped Joseph Kennedy to obtain the ambassador to Great Britain. Corcoran, who was very close to James Roosevelt, got dragged into this scandal. It was not the first time that Corcoran had been accused of corrupt behaviour. Norman M. Littell, a high-ranking Justice Department official, told Anna Roosevelt that Corcoran had become a liability to her father: No quality is so essential in government as simple integrity and forthrightness. Ability and brilliance of mind are not enough."

Corcoran's fascist sympathies resulted in him becoming a firm advocate of isolationism. He told friends that Irish Americans liked him "remembered their parents' repression at the hands of the British". On one occasion, Harry Hopkins told Corcoran: "Tom you're too Catholic to trust the Russians and too Irish to trust the English."

Tommy Corcoran now found himself outside the inner circle. In 1940 he began telling friends that he was considering leaving government. He told Samuel Irving Rosenman: "I want to make a million dollars in one year, that's all. Then I'm coming back to the government for the rest of my life." Corcoran's plan was to become a political lobbyist on behalf of companies seeking to obtain government contracts. A large number of government officials had their jobs because of Corcoran. It was payback time.

One day in early October 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt told Corcoran that he wanted him to resign from the administration. He wanted him to carry out a covert mission and it was "too politically dangerous" to do this while serving in his government.

Roosevelt believed that the best way of stopping Japanese imperialism in Asia was to arm the Chinese government of Chiang Kai-shek. However, Congress was opposed to this idea as it was feared that this help might trigger a war with Japan. Therefore, Roosevelt's plan was for Corcoran to establish a private corporation to provide assistance to the nationalist government in China. Roosevelt even supplied the name of the proposed company, China Defense Supplies. He also suggested that his uncle, Frederick Delano, should be co-chairman of the company. Chiang nominated his former finance minister, Tse-ven Soong, as the other co-chairman.

For reasons of secrecy, Corcoran took no title other than outside counsel for China Defense Supplies. William S. Youngman was his frontman in China. Corcoran's friend, Whitey Willauer, was moved to the Foreign Economic Administration, where he supervised the sending of supplies to China. In this way Corcoran was able to create an Asian Lend-Lease program.

Corcoran also worked closely with Claire Lee Chennault, who had been working as a military adviser to Chiang Kai-shek since 1937. Chennault told Corcoran that if he was given the resources, he could maintain an air force within China that could carry out raids against the Japanese. Corcoran returned to the United States and managed to persuade Franklin D. Roosevelt to approve the creation of the American Volunteer Group.

One hundred P-40 fighters, built by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, intended for Britain, were redirected to Chennault in China. William Pawley was Curtiss-Wright's representative in Asia and he arranged for the P-40 to be assembled in Rangoon. It was Tommy Corcoran's son David who suggested that the American Volunteer Group should be called the Flying Tigers. Chennault liked the idea and asked his friend, Walt Disney, to design a tiger emblem for the planes.

On 13th April, 1941, Roosevelt signed a secret executive order authorizing the American Volunteer Group to recruit reserve officers from the army, navy and marines. Pawley suggested that the men should be recruited as "flying instructors".

In July, 1941, ten pilots and 150 mechanics were supplied with fake passports and sailed from San Francisco for Rangoon. When they arrived they were told that they were really involved in a secret war against Japan. To compensate for the risks involved, the pilots were to be paid $600 a month ($675 for a patrol leader). In addition, they were to receive $500 for every enemy plane they shot down.

The Flying Tigers were extremely effective in their raids on Japanese positions and helped to slow down attempts to close the Burma Road, a key supply route to China. In seven months of fighting, the Flying Tigers destroyed 296 planes at a loss of 24 men (14 while flying and 10 on the ground).

Tommy Corcoran had originally been an isolationist. However, he now knew that he could make a fortune out of the arms trade. His first major client was Henry J. Kaiser, a successful businessman from California. Corcoran had helped Kaiser obtain lucrative government contracts while working for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

Kaiser paid Corcoran a retainer of $25,000 a year. Corcoran then introduced Kaiser to William S. Knudsen, head of the Office of Production Management. Over the next few years Kaiser obtained $645 million in building contracts at his ten shipyards. Kaiser's two main business partners were Stephen D. Bechtel and John A. McCone. Kaiser had worked with Bechtel in the 1930s to build many of the major roads throughout California.

In 1937 McCone became president of Bechtel-McCone. On the outbreak of the Second World War McCone joined forces with Kaiser and Bechtel to establish the California Shipbuilding Company. With the help of Corcoran, the company obtained large government contracts to build ships. In 1946 it was reported that the company had made $44 million in wartime profits.

Corcoran was also informed that a great deal of magnesium would be needed for building aircraft. With the help of Jesse H. Jones, the boss of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, Kaiser was granted a loan to build a magnesium production plant in San Jose, California. After the RFC loan was secured, Corcoran sent Kaiser a bill requesting $135,000 in cash and a 15% stake in the magnesium production business.

Another important client was the Houston contracting firm of Brown & Root, owned by George R. Brown and Herman Brown. These brothers had been the major financiers of the political campaigns of Lyndon B. Johnson. Corcoran arranged for the two men to meet William S. Knudsen. Records show that Corcoran was paid $15,000 for "advice, conferences and negotiations" related to shipbuilding contracts.

In 1942 the Brown brothers established the Brown Shipbuilding Company on the Houston Ship Channel. Over the next three years the company built 359 ships and employed 25,000 people. This brought in revenue of $27,000,000. The government shipbuilding contract was eventually worth $357,000,000. Yet until they got the contract, Brown & Root had never built a single ship of any type.

Corcoran's work with China Defense Supplies caused some disquiet in Roosevelt's administration. Henry Morgenthau was a prominent critic. He argued that in effect, Corcoran was running an off-the-books operation in which a private company was diverting some of the war material destined for China to a private army, the American Volunteer Group.

Resistance also came from General George Marshall and General Joseph Stilwell, the American commander in Asia. Marshall and Stilwell both believed that Chiang Kai-shek was completely corrupt and needed to be forced into introducing reforms. Stilwell complained about Corcoran's ability to present Chiang in the best possible light with Roosevelt. Stilwell wrote to Marshall that the "continued publication of Chungking propaganda in the United States is an increasing handicap to my work." He added, "we can pull them out of this cesspool, but continued concessions have made the Generalissimo believe he has only to insist and we will yield."

Corcoran was also coming under pressure from the work he was doing for Sterling Pharmaceutical. His brother, David worked for the company and was responsible for getting Corcoran the contract. However, it was revealed in 1940 that Sterling Pharmaceutical had strong links with I. G. Farben. The FBI discovered that Sterling had conspired with Farben to control the sale of aspirin. In other words, had formed an aspirin cartel. According to one FBI report, Sterling were employing Nazi sympathizers in its offices in Latin America. Rumours began to circulate that Burton Wheeler would announce that he was appointing a subcommittee to investigate the relations between American and German firms.

Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold announced he was ready to prosecute any American company aiding and abetting a German company in any part of the world. On 10th April, 1941, the Department of Justice issued subpoenas to Sterling Pharmaceutical. Soon afterwards newspapers began to run negative stories about the company. One claimed that Sterling was helping the Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels fulfill his pledge that "Americans would help Hitler win the Americas."

On 2nd June, 1941, Roosevelt appointed Francis B. Biddle as his new Attorney General. Biddle was a close friend of Corcoran's. The day after his appointment, Biddle accepted a settlement offer from Sterling in which the company would pay a fine of five thousand dollars. Later, it was agreed that Sterling would abrogate all contracts with I. G. Farben.

In Congress there was speeches made calling for an investigation into the role played by Corcoran in protecting the interests of Sterling Pharmaceutical. Senator Lawrence Smith argued: "It is common gossip in government circles that the long arm of Tommy Corcoran reaches into many agencies; that he has placed many men in important positions and they in turn are amenable to his influences."

Corcoran had also developed a close relationship with Lyndon B. Johnson. On 4th April, 1941, Texas senator, Morris Sheppard died. Corcoran agreed to help Johnson in his campaign to replace Sheppard. This included helping Johnson obtain approval of a rural electrification project from the Rural Electrification Administration. Corcoran also arranged to Franklin D. Roosevelt to make a speech on the eve of the polls criticizing Johnson's opponent, Wilbert Lee O'Daniel. Despite the efforts of Corcoran, O'Daniel defeated Johnson by 1,311 votes.

On the suggestion of Alvin J. Wirtz, Johnson decided to acquire KTBC, a radio station in Austin. E. G. Kingsberry and Wesley West, agreed to sell KTBC to Johnson (officially it was purchased by his wife, Lady Bird Johnson). However, it needed the approval of the Federal Communications Commission (FCR). Johnson asked Corcoran for help with this matter. This was not very difficult as the chairman of the FCR, James Fly, was appointed by Frank Murphy as a favour for Corcoran. The FCC eventually approved the deal and Johnson was able to use KTBC to amass a fortune of more than $25 million.

Rumours continued to circulate about Corcoran's illegal activities. Harry S. Truman accused Todd Shipyards of hiring Corcoran to help win government contracts. In September, 1941, the New York Times reported that Corcoran was responsible for obtaining favourable treatment in the settlement of the Justice Department case brought against Sterling Pharmaceutical. Another newspaper reported that Vice President Henry Wallace "disapproves of the way Mr. Corcoran has capitalized on the government associations to promote his lucrative 'law' practice."

On 16th December, 1941, Corcoran appeared before the Senate Defense Investigation Committee. He admitted that business had been exceedingly good since he left Roosevelt's administration. Some members of the committee were convinced that Corcoran's activities revealed a need for more stringent lobbying restrictions. Senator Carl Hatch from New Mexico introduced a bill that would prohibit former government employees from working with government departments or agencies for two years after leaving government service. As David McKean points out in Peddling Influence, "the bill never made it out of the Judiciary Committee, presumably because Washington lobbyists persuaded their friends on the panel to kill it."

After the United States entered the war against Japan, Germany and Italy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Roosevelt selected Colonel William Donovan as the first director of the organization, who had spent some time studying the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization set up by the British government in July 1940. The OSS had responsibility for collecting and analyzing information about countries at war with the United States.

The OSS gradually took over the activities that Corcoran had helped set up in China. In 1943 OSS agents based in China included Paul Helliwell, E. Howard Hunt, Mitch Werbell, Lucien Conein, John Singlaub and Ray Cline. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, some OSS members in China were paid for their work with five-pound sacks of opium.

In a letter to the Senate Defense Investigation Committee in November, 1944, Norman M. Littell, assistant attorney general for the lands division, reported conversations between Tommy Corcoran and Francis Biddle that suggested that the two men had a corrupt relationship. Littell claimed that Biddle seemed to be following instructions from Corcoran. In the letter, Littell asked the committee: "What has Tommy Corcoran got on Biddle?"

Littell argued that during the investigation of the Sterling Pharmaceutical case, Biddle was "completely dominated by Tommy Corcoran". He added that this company was acting as "an agent of Nazi Germany" and that Biddle's decision to settle this case was "the lowest point in the history of the Department of Justice since the Harding administration".

This story was picked up by the national press and demands were made that the relationship between Biddle and Corcoran should be investigated. Sam Rayburn made sure that no committee held a hearing on this issue. Charles Van Devander reported in the Washington Post that: "Strong influence is being brought to bear to block an investigation by Congress into the affairs of the Department of Justice, including Attorney General Biddle's allegedly close relationship with lawyer lobbyist Tommy Corcoran."

One moth after the dropping the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Tommy Corcoran joined with David Corcoran and William S. Youngman to create a Panamanian company, Rio Carthy, for the purpose of pursuing business ventures in Asia and South America. Soon afterwards, Claire Lee Chennault and Whiting Willauer approached Corcoran with the idea of creating a commercial airline in China to compete with CNAC and CATC. Corcoran agreed to use Rio Cathy as the legal vehicle for investing in the airline venture. Chiang Kai-shek agreed that his government would invest in the airline. Corcoran anticipated he would own 37% of the equity in the airline, but Chennault and Willauer gave a greater percentage to the Chinese government, and Corcoran's share dropped to 28%.

Civil Air Transport (CAT) was officially launched on 29th January, 1946. Corcoran approached his old friend Fiorella LaGuardia, the director general of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). He agreed to award a $4 million contract to deliver relief to China. This contract kept them going for the first year but as the civil war intensified, CAT had difficulty maintaining its routes.

The OSS had been disbanded in October 1945 and was replaced by the War Department's Strategic Service Unit (SSU). Paul Helliwell became chief of the Far East Division of the SSU. In 1947 the SSU was replaced by the Central Intelligence Agency.

CAT needed another major customer and on 6th July, 1947, Corcoran and Claire Lee Chennault had a meeting with Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter, the new director of the CIA. Hillenkoetter arranged for Corcoran to meet Frank Wisner, the director of the Office of Policy Coordination. Wisner was in charge of the CIA's covert operations.

On 1st November, 1948, Corcoran signed a formal agreement with the CIA. The agreement committed the agency to provide up to $500,000 to finance an CAT airbase, and $200,000 to fly agency personnel and equipment in and out of the mainland, and to underwrite any shortfall that might result from any hazardous mission. Over the next few months CAT airlifted personnel and equipment from Chungking, Kweilin, Luchnow, Nanking, and Amoy.

In 1948, Lyndon B. Johnson decided to make a second run for the U.S. Senate. His main opponent in the Democratic primary (Texas was virtually a one party state and the most important elections were those that decided who would be the Democratic Party candidate) was Coke Stevenson. Johnson was criticized by Stevenson for supporting the Taft-Hartley Act. The American Federation of Labor was also angry with Johnson for supporting this legislation and at its June convention the AFL broke a 54 year tradition of neutrality and endorsed Stevenson.

Johnson asked Tommy Corcoran to work behind the scenes at convincing union leaders that he was more pro-labor than Stevenson. This he did and on 11th August, 1948, Corcoran told Harold Ickes that he had "a terrible time straightening out labor" in the Johnson campaign but he believed he had sorted the problem out.

On 2nd September, unofficial results had Stevenson winning by 362 votes. However, by the time the results became official, Johnson was declared the winner by 17 votes. Stevenson immediately claimed that he was a victim of election fraud. On 24th September, Judge T. Whitfield Davidson, invalidated the results of the election and set a trial date.

Johnson once again approached Corcoran to solve the problem. A meeting was held that was attended by Corcoran, Francis Biddle, Abe Fortas, Joe Rauh, Jim Rowe and Ben Cohen. It was decided to take the case directly to the Supreme Court. A motion was drafted and sent to Justice Hugo Black. On 28th September, Justice Black issued an order that put Johnson's name back on the ballot. Later, it was claimed by Rauh that Black made the decision following a meeting with Corcoran.

On 2nd November, 1948, Johnson easily defeated Jack Porter, his Republican Party candidate. Coke Stevenson now appealed to the subcommittee on elections and privileges of the Senate Rules and Administration Committee. Corcoran enjoyed a good relationship with Senator Styles Bridges of New Hampshire. He was able to work behind the scenes to make sure that the ruling did not go against Johnson. Corcoran later told Johnson that he would have to repay Bridges for what he had done for him regarding the election. The Johnson-Stevenson case was also investigated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Johnson was eventually cleared by Hoover of corruption and was allowed to take his seat in the Senate.

In 1949 Sam Zemurray asked Corcoran to join the United Fruit Company as a lobbyist and special counsel. Zemurray had problems with his business in Guatemala. In the 1930s Zemurray aligned United Fruit closely with the government of President Jorge Ubico. The company received import duty and real estate tax exemptions from Ubico. He also gave them hundreds of square miles of land. United Fruit controlled more land than any other individual or group. It also owned the railway, the electric utilities, telegraph, and the country's only port at Puerto Barrios on the Atlantic coast.

Ubico was overthrown in 1944 and following democratic elections, Juan Jose Arevalo became the new president. Arevalo, a university professor who had been living in exile, described himself as a "spiritual socialist". He implemented sweeping reforms by passing new laws that gave workers the right to form unions. This included the 40,000 Guatemalans who worked for United Fruit.

Zemurray feared that Arevalo would also nationalize the land owned by United Fruit in Guatemala. He asked Corcoran to express his fears to senior political figures in Washington. Corcoran began talks with key people in the government agencies and departments that shaped U.S. policy in Central America. He argued that the U.S. should use United Fruit as an American beachhead against communism in the region.

In January, 1950, Civil Air Transport (CAT) relocated its base of operations to the island of Formosa, where Chiang Kai-shek had established his new government. The following month, the Soviet Union and China signed a mutual defense pact. Two weeks later, President Harry S. Truman signed National Security Directive 64, which stated that “it is important to United states security interests that all practical measures be taken to prevent further communist expansion in Southeast Asia.”

The support of the government in Formosa was to become a key aspect of this policy. In February 1950, Frank Wisner began negotiating with Corcoran for the purchase of CAT. “In March, using a ‘cutout’ banker or middleman, the CIA paid CAT $350,000 to clear up arrearages, $400,000 for future operations, and a $1 million option on the business. The money was then divided among the airline’s owners, with Corcoran and Youngman receiving more than $100,000 for six years of legal fees, and Corcoran, Youngman, and David Corcoran dividing approximately $225,000 from the sale of the airline.” Paul Helliwell was put in charge of this operation. His deputy was Desmond FitzGerald. Helliwell's main job was to help Chiang Kai-shek to prepare for a future invasion of Communist China. The CIA created a pair of front companies to supply and finance the surviving forces of Chiang's KMT. Helliwell w as put in charge of this operation. This included establishing the Sea Supply Corporation, a shipping company in Bangkok.

The CIA now launched a secret war against China. An office under commercial cover called Western Enterprises was opened on Taiwan. Training and operational bases were established in Taiwan and other offshore islands. By 1951 Chiang Kai-shek claimed to have more than a million active guerrillas in China. However, according to John Prados, “ United States intelligence estimates at the time carried the more conservative figure of 600,000 or 650,000, only half of whom could be considered loyal to Taiwan.”

After the war Tommy Corcoran continued his work as a paid lobbyist for Sam Zemurray and the United Fruit Company. Zemurray became concerned that Captain Jacobo Arbenz, one of the heroes of the 1944 revolution, would be elected as the new president of Guatemala. In the spring of 1950, Corcoran went to see Thomas C. Mann, the director of the State Department’s Office of Inter-American Affairs. Corcoran asked Mann if he had any plans to prevent Arbenz from being elected. Mann replied: “That is for the people of that country to decide.”

Unhappy with this reply, Corcoran paid a call on the Allen Dulles, the deputy director of the CIA. Dulles, who represented United Fruit in the 1930s, was far more interested in Corcoran’s ideas. “During their meeting Dulles explained to Corcoran that while the CIA was sympathetic to United Fruit, he could not authorize any assistance without the support of the State Department. Dulles assured Corcoran, however, that whoever was elected as the next president of Guatemala would not be allowed to nationalize the operations of United Fruit.”

However, political groups continued to resort to violence and in 1949 Major Francisco Arana was murdered. The following year Arbenz defeated Manuel Ygidoras to become Guatemala's new president. Arbenz, who obtained 65% of the votes, took power on 15th March, 1951. Corcoran then recruited Robert La Follette to work for United Fruit. Corcoran arranged for La Follette to lobby liberal members of Congress. The message was that Arbenz was not a liberal but a dangerous left-wing radical.

This strategy was successful and Congress was duly alarmed when on 17 th June, 1952, Arbenz announced a new Agrarian Reform program . This included expropriating idle land on government and private estates and redistributed to peasants in lots of 8 to 33 acres. The Agrarian Reform program managed to give 1.5 million acres to around 100,000 families for which the government paid $8,345,545 in bonds. Among the expropriated landowners was Arbenz himself, who had become into a landowner with the dowry of his wealthy wife. Around 46 farms were given to groups of peasants who organized themselves in cooperatives.

In March 1953, 209,842 acres of United Fruit Company's uncultivated land was taken by the government which offered compensation of $525,000. The company wanted $16 million for the land. While the Guatemalan government valued $2.99 per acre, the American government valued it at $75 per acre. As David McKean has pointed out: This figure was “in line with the company’s own valuation of the property, at least for tax purposes”. However, the company wanted $16 million for the land. While the Guatemalan government valued it at $2.99 per acre, the company now valued it at $75 per acre.

Corcoran contacted President Anastasio Somoza and warned him that the Guatemalan revolution might spread to Nicaragua. Somoza now made representations to Harry S. Truman about what was happening in Guatemala. After discussions with Walter Bedell Smith, director of the CIA, a secret plan to overthrow Arbenz (Operation Fortune) was developed. Part of this plan involved Tommy Corcoran arranging for small arms and ammunition to be loaded on a United Fruit freighter and shipped to Guatemala, where the weapons would be distributed to dissidents. When the Secretary of State Dean Acheson discovered details of Operation Fortune, he had a meeting with Truman where he vigorously protested about the involvement of United Fruit and the CIA in the attempted overthrow of the democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz. As a result of Acheson’s protests, Truman ordered the postponement of Operation Fortune.

Tommy Corcoran’s work was made easier by the election of Dwight Eisenhower in November, 1952. Eisenhower’s personal secretary was Anne Whitman, the wife of Edmund Whitman, United Fruit’s public relations director. Eisenhower appointed John Peurifoy as ambassador to Guatemala. He soon made it clear that he believed that the Arbenz government posed a threat to the America’s campaign against communism.

Corcoran also arranged for Whiting Willauer, his friend and partner in Civil Air Transport, to become U.S. ambassador to Honduras. As Willauer pointed out in a letter to Claire Lee Chennault, he worked day and night to arrange training sites and instructors plus air crews for the rebel air force, and to keep the Honduran government “in line so they would allow the revolutionary activity to continue.”

Eisenhower also replaced Dean Acheson with John Foster Dulles. His brother, Allen Dulles became director of the CIA. The Dulles brothers “had sat on the board of United Fruit’s partner in the banana monopoly, the Schroder Banking Corporation” whereas “U.N. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge was a stockholder and had been a strong defender of United Fruit while a U.S. senator.”

Walter Bedell Smith was moved to the State Department. Smith told Corcoran he would do all he could to help in the overthrow of Arbenz. He added that he would like to work for United Fruit once he retired from government office. This request was granted and Bedell Smith was later to become a director of United Fruit. According to John Prados, the author of The Presidents' Secret War, Corcoran’s meeting with “Undersecretary of State Walter Bedell Smith that summer and that conversation is recalled by CIA officers as the clear starting point of that plan.” Evan Thomas, the author of The Very Best Me; Daring Early Years of the CIA (2007) has added that: “With his usual energy and skill, Corcoran beseeched the U. S. government to overthrow Arbenz”.

The new CIA plan to overthrow Jacobo Arbenz was called “Operation Success”. Allen Dulles became the executive agent and arranged for Tracey Barnes and Richard Bissell to plan and execute the operation. Bissell later claimed that he had been aware of the problem since reading a document published by the State Department that claimed: “The communists already exercise in Guatemala a political influence far out of proportion to their small numerical strength. This influence will probably continue to grow during 1952. The political situation in Guatemala adversely effects U. S. interests and constitutes a potential threat to U.S. security.” Bissell does not point out that the source of this information was Tommy Corcoran and the United Fruit Company.

John Prados argues that it was Barnes and Bissell who “coordinated the Washington end of the planning and logistics for the Guatemala operation.” As Deputy Director for Plans, it was Frank Wisner’s responsibility to select the field commander for Operation Success. Kim Roosevelt was first choice but he turned it down and instead the job went to Albert Hanley, the CIA station Chief in Korea.

Hanley was told to report to Joseph Caldwell King, director of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division. King had previously worked for the FBI where he had responsibility for all intelligence operations in Latin America. King suggested Hanley meet Tommy Corcoran. Hanley did not like the idea. King replied: “If you think you can run this operation without United Fruit you’re crazy.” Although Hanley refused to work with Corcoran, Allen Dulles kept him fully informed of the latest developments in planning the overthrow of Arbenz.

Tracey Barnes brought in David Atlee Phillips to run a “black” propaganda radio station. According to Phillips, he was reluctant to take part in the overthrow of a democratically elected president. Barnes replied: “It’s not a question of Arbenz. Nor of Guatemala. We have solid intelligence that the Soviets intended to throw substantial support to Arbenz… Guatemala is bordered by Honduras, British Honduras, Salvador and Mexico. It’s unacceptable to have a Commie running Guatemala.”

Barnes also appointed E. Howard Hunt as chief of political action. In his autobiography, Undercover (1975), Hunt claims that “Barnes swore me to special secrecy and revealed that the National Security Council under Eisenhower and Vice President Nixon had ordered the overthrow of Guatemala’s Communist regime.” Hunt was not convinced by this explanation. He pointed out that 18 months previously he had suggested to the director of the CIA that Arbenz needed to be dealt with. However, the idea had been rejected. Hunt was now told that: “ Washington lawyer Thomas G. Corcoran had, among his clients, the United Fruit Company. United Fruit, like many American corporations in Guatemala had watched with growing dismay nationalization, confiscation and other strong measures affecting their foreign holdings. Finally a land-reform edict issued by Arbenz proved the final straw, and Tommy the Cork had begun lobbying in behalf of United Fruit and against Arbenz. Following this special impetus our project had been approved by the National Security Council and was already under way.”

Albert Hanley brought in Rip Robertson to take charge of the paramilitary side of the operation. Robertson had been Hanley’s deputy in Korea and had “enjoyed going along on the behind-the-lines missions with the CIA guerrillas, in violation of standing orders from Washington.” One of those who worked with Robertson in Operation Success was David Morales. Also in the team was Henry Hecksher, who operated under cover in Guatemala to supply front-line reports.

John Foster Dulles decided that he “needed a civilian adviser to the State Department team to help expediate Operation Success. Dulles chose a friend of Corcoran’s, William Pawley, a Miami-based millionaire”. David McKean goes on to point out that Pawley had worked with Corcoran, Chennault and Willauer in helping to set up the Flying Tigers and in transforming Civil Air Transport into a CIA airline. McKean adds that his most important qualification for the job was his “long association with right-wing Latin America dictators.”

The rebel “liberation army” was formed and trained in Nicaragua. This was not a problem as President Anastasio Somoza and been warning the United States government since 1952 that that the Guatemalan revolution might spread to Nicaragua. The rebel army of 150 men were trained by Rip Robertson. Their commander was a disaffected Guatemalan army officer, Carlos Castillo Armas.

It was clear that a 150 man army was unlikely to be able to overthrow the Guatemalan government. Tracey Barnes believed that if the rebels could gain control of the skies and bomb Guatemala City, they could create panic and Arbenz might be fooled into accepting defeat.

According to Richard Bissell, Somoza was willing to provide cover for this covert operation. However, this was on the understanding that these aircraft would be provided by the United States. Dwight Eisenhower agreed to supply Somoza with a “small pirate air force to bomb Arbenz into submission”. To fly these planes, the CIA recruited American mercenaries like Jerry DeLarm.

Before the bombing of Guatemala City, the rebel army was moved to Honduras where Tommy Corcoran’s business partner, Whiting Willauer, was ambassador. The plan was for them to pretend to be the “vanguard of a much larger army seeking to liberate their homeland from the Marxists”.

Arbenz became aware of this CIA plot to overthrow him. Guatemalan police made several arrests. In his memoirs, Eisenhower described these arrests as a “reign of terror” and falsely claimed that “agents of international Communism in Guatemala continued their efforts to penetrate and subvert their neighboring Central American states, using consular agents for their political purposes and fomenting political assassinations and strikes."

Sydney Gruson of the New York Times began to investigate this story. Journalists working for Time Magazine also tried to write about these attempts to destabilize Arbenz’s government. Frank Wisner, head of Operation Mockingbird, asked Allen Dulles to make sure that the American public never discovered the plot to overthrow Arbenz. Arthur Hays Sulzberger, the publisher of the New York Times, agreed to stop Gruson from writing the story. Henry Luce was also willing to arrange for the Time Magazine reports to be rewritten at the editorial offices in New York.

The CIA propaganda campaign included the distribution of 100,000 copies of a pamphlet entitled Chronology of Communism in Guatemala . They also produced three films on Guatemala for showing free in cinemas. Faked photographs were distributed that claimed to show the mutilated bodies of opponents of Arbenz.

David Atlee Phillips and E. Howard Hunt were responsible for running the CIA's Voice of Liberation radio station. Broadcasts began on 1 st May, 1954. They also arranged for the distribution of posters and pamphlets. Over 200 articles based on information provided by the CIA were placed in newspapers and magazines by the United States Information Agency.

The Voice of Liberation reported massive defections from Arbenz’s army. According to David Atlee Phillips the radio station “broadcast that two columns of rebel soldiers were converging on Guatemala City. In fact, Castillo Armas and his makeshift army were still encamped six miles inside the border, far from the capital.” As Phillips later admitted, the “highways were crowded, but with frightened citizens fleeing Guatemala City and not with soldiers approaching it.”

As E. Howard Hunt pointed out, “our powerful transmitter overrode the Guatemalan national radio, broadcasting messages to confuse and divide the population from its military overlords.” There was no popular uprising. On 20 th June, the CIA reported to Dwight Eisenhower that Castillo Armas had not been able to take his assigned objective, Zacapa. His seaborne force had also failed to capture Puerto Barrios.

According to John Prados, it all now depended on “Whiting Willauer’s rebel air force”. However, that was not going to plan and on 27th June, Winston Churchill, the British prime minister berated Eisenhower when a CIA plane sank a British merchant vessel heading for Guatemala. The bombing had been ordered by Rip Robertson without first gaining permission from the CIA or Eisenhower. Robertson had been convinced that the Springfjord was a “Czech arms carrying freighter”. In reality it had been carrying only coffee and cotton. Frank Wisner had to make a personal apology for the incident and the CIA later quietly reimbursed Lloyd’s of London, insurers of the Springfjord , the $1.5 million they had paid out on the ship.

Arbenz had been convinced by the Voice of Liberation reports that his army was deserting. Richard Bissell believes that this is when Arbenz made his main mistake. Jacobo Arbenz decided to distribute weapons to the “people’s organizations and the political parties”. As Bissell later explained: “The conservative men who constituted the leadership of Guatemala’s army viewed this action as the final unacceptable leftward lurch, and they told Arbenz they would no longer support him. He resigned and fled to Mexico.”President Harry Truman became highly suspicious of Corcoran's activities and he arranged for FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to place a tap on his phone. Despite his shady business dealings he was never convicted of a criminal offence.

Thomas Corcoran died on 7th December, 1981.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Dallek, Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and His Times (1991)

By the middle of 1937, FDR, worried that deficit spending was leading to high inflation, believed that the government needed to curb its outlays. Ickes, who had jurisdiction over the PWA, feared that money allocated to Texas dams would line the pockets of builders overcharging the government. In the summer of 1937, however, Johnson persuaded the White House to commit another $5 million to the Marshall Ford Dam, a third of the additional $15.5 million promised in 1935. The prospect of throwing some 2000 men out of work and of halting construction on a project that would ultimately save Texas millions of dollars in flood damages played a large part in the decision. Unless the Marshall Ford construction was continued, an LCRA memo warned, 80 percent of the 2500 men on the job would be fired, and floods, like one in June 1935 costing over $10 million, would continue to plague south-central Texas. On July 21, in a ceremony at the White House, James Roosevelt, the President's son and secretary, handed Johnson, who was accompanied by Wirtz and members of the LCRA Board, the President's order granting the $5 million. Joking with the delegation, Jimmy Roosevelt said that Johnson "had kept him busy so much of the time on the Texas project," that he "`will have to catch up on his sleep' now." "`The president is happy to do this for your congressman,' " Jimmy added. In response to repeated prodding by Johnson, the Administration provided another $14 million over the next four years to complete the network of Texas dams. The expenditure paid handsome dividends in lower unemployment, flood prevention, and more abundant and cheaper electric power.

The dam-building also served Lyndon's political interests and the well-being of Brown & Root, a construction company in Austin controlled by George and Herman Brown. With Lyndon's help they won government contracts that turned a small road-building firm into a multi-million dollar business. Their success gave Lyndon a financial angel that could help secure his political future. As Tommy Corcoran put it later, "A young guy might be as wise as Solomon, as winning as Will Rogers and as popular as Santa Claus, but if he didn't have a firm financial base his opponents could squeeze him. When Roosevelt told me to take care of the boy," Corcoran added, "that meant to watch out for his financial backers too. In Lyndon's case there was just this little road building firm, Brown and Root, run by a pair of Germans."

(2) Robert A. Caro, Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate (2002)

Jenkins wrote Warren Woodward on January 11, "Ed Clark tells me that he has received some assistance from H. E. Butt. I wonder if you could go by and pick it up and put it with the other (we) put away before I left Texas Clark says that Brown's money was for the presidential run for which Johnson was gearing up that January, and that Butt's was for Johnson to contribute to the campaigns of other senators, but that often he and the other men providing Johnson with funds weren't even sure which of these two purposes the funding were for. "How could you know?" Ed Clark was to say. "If Johnson wanted to give some senator money for some campaign, Johnson would pass the word to give money to me or Jesse Kellam or Cliff Carter, and it would find its way into Johnson's hands. And it would be the same if he wanted money for his own campaign. And a lot of the money that was given to Johnson both for other candidates and for himself was in cash." "All we knew was that Lyndon asked for it, and we gave it," Tommy Corcoran was to say.

This atmosphere would pervade Lyndon Johnson's fundraising all during his years in the Senate. He would "pass the word" - often by telephoning, sometimes by having Jenkins telephone - to Brown or dark or Connally, and the cash would be collected down in Texas and flown to Washington, or, a Johnson was in Austin, would be delivered to him there. When word was received that some was available, John Connally recalls, he would board a plane in Fort Worth or Dallas, and "I'd go get it. Or Walter would get it. Woody would go get it. We had a lot of people who would go get it, and deliver it. The idea that Walter or Woody or Wilton Woods would skim some is ridiculous. We had couriers." Or, dark says, "If George or me were going up anyway, we'd take it ourselves." And Tommy Corcoran was often bringing Johnson cash from New York unions, mostly as contributions to liberal senators whom the unions wanted to support. Asked how he knew that the money "found its way" into Johnson's hands, Clark laughed and said, "Because sometimes I gave it to him. It would be in an envelope." Both Clark and Wild said that Johnson wanted the contributions given, outside the office, to either Jenkins or Bobby Baker, or to another Johnson aide. Cliff Carter, but neither Wild nor Clark trusted either Baker or Carter.

(3) Jake Esterline was interviewed by Jack Pfeiffer on 10th November, 1975.

Jack Pfeiffer: I have a question, and it is what was Pawley's relation to this whole operation... and your relation with Pawley seems to have been quite close, too.

Jake Esterline: I think it was a hangover relationship from the things that Bill Pawley had done as quite a wheel with a number of very senior people during the Guatemalan operation ... that they felt that Bill, who had been very closely tied into Cuba ... that he was a very prominent man in Florida... that there were a lot of things that he might be able to do, in the sense of getting things lined up in Florida for us... and also his ties with Nixon and with other republican politicos. I used to deal with him quite a bit before.... From my point of view, we never let Bill Pawley know any of the intimacies about our operations, or what we were doing. He never knew where our bases were, or things of that sort. He never knew anything specific about our operations, but he was doing an awful lot of things on his own with the exiles. Some of the people that he had known in Cuba, in the sugar business, etc. I guess he actually was instrumental in running boats and things in and out of Cuba, getting people out and what not, and a variety of things that were not connected with us in any way. He was a political factor from the standpoint from J.C.'s standpoint. I don't know whether Tommy Corcoran entered in at this point... I think Tommy Corcoran was strictly in Guatemala. I guess Corcoran didn't come into this thing, at least not very much.

Jack Pfeiffer: His name turns up once or twice.

Jake Esterline: Yes, I met him once, in connection with Cuba, but I don't remember who... for J.C King, but I don't remember why, at this point. It wasn't anything of any significance. My feeling with Pawley... he was such a hawk, and he was every second week... he wanted to kill somebody inside... . It was from my standpoint - we were trying to keep him from doing things to cause problems for us. This was almost a standing operation.

Jack Pfeiffer: This is what I was wondering, because Tracy Barnes, I know on a number of occasions, seemed to make it quite clear that what the Agency had to be careful of was getting hung with a reactionary label, and then at the same time that was going on, here is all of this conversation back and forth with Pawley and his visits...

Jake Esterline: Really to keep him from doing something to upset the applecart from our standpoint. In that sense, I did fill that role in part for a long time; and the net result of the thing is that Bill thinks I am a dangerous leftist today. If I hadn't been a foot dragger, or hadn't taken all these dissenting opinions of this, things in Cuba would have been a lot better.

Jack Pfeiffer: Was Pawley actually involved in the covert operation in Guatemala?

Jake Esterline: Yes, he, well I am sure he was, in a...

Jack Pfeiffer: I mean, with you as far as you...

Jake Esterline: Not I personally, but he was involved with State Department. I said Rubottom a couple of times, I didn't mean Rubottom, I meant Rusk. He was involved - especially in Guatemala with Rubottom or whoever Secretary of State was, and Seville Sacassaa and Somoza and whoever Secretary of Defense was in getting the planes from the Defense Dept., having them painted over, the decals painted over and flown to Nicaragua where they became the Defense force for that operation.

Jack Pfeiffer: I ran across some comment that he had made to Livingston Merchant.

Jake Esterline: They were good friends, and knew each other. But to my knowledge, he never had any involvement like that during the Bay of Pigs days, although you'd have to ask Ted Shackley about what they did later, because I think he ran some things into Cuba for Ted Shackley.

Jack Pfeiffer: That is beyond my period of interest. He was involved in a great amount of fund raising activity, in the New York area apparently - pushing or raising funds in the New York area - wasn't Droller involved in this too? What was your relation with Droller... were you directing Droller's activities, or was Dave Phillips running Droller...

Jake Esterline: Oh, I sort of ran Droller, except I never knew what Tracy Barnes was going to do next, when I turned my back. Droller was such.an ambitious fellow trying to run in... trying to run circles around everybody for his own aggrandizement that you never knew... but Droller would never have had any continuing contact with Pawley, because they had met only once, and I recall Pawley saying that he never wanted to talk to that "you know what" again. He was very unhappy that somebody like Gerry... he just didn't like Gerry's looks, he didn't like his accent. He was very unfair about Gerry, and I don't mean to be unfair about Gerry - the only thing is that Gerry was insanely ambitious. He was his own worst enemy, that was all.... We just didn't think that Tracy really understood it that well, or if Tracy did, he coudn't articulate... he wouldn't articulate it that well. Tracy was one of the sweetest guys that ever lived, but he coudn't ever draw a straight line between two points....

Jack Pfeiffer: What about JFK?

Jake Esterline: JFK was an uninitiated fellow who had been in the wars, but he hadn't been exposed to any world politics or crises yet if he had something else as a warm up, he might have made different decisions than he made at that time. I think he was kind of a victim of the thing. I blame Nixon far more than I do Kennedy for the equivocations and the loss of time and what not that led to the ultimate disaster. Goodwin, I just thought was a sleazy; little self-seeker, who I didn't feel safe with any secret. His consorting with Che Guevara in Montevideo had rather upset me at the time...

Jack Pfeiffer: How about McNamara did you get involved with him at all?

Jake Esterline: No.

Jack Pfeiffer: Bobby Kennedy?

Jake Esterline: I wouldn't even tell you off tape. I didn't like him. He's dead, God rest his soul.

(4) Ray S. Cline, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA (1976)

Thomas G. (Tommy) Corcoran, Washington's durable political lawyer and an early New Deal "brain-truster" from Harvard Law School, says that his greatest contribution to government in his long career was helping infiltrate smart young Harvard Law School products into every agency of government. He felt the United States needed to develop a highly educated, highly motivated public service corps that had not existed before Roosevelt's time. Donovan did much the same for career experts in international affairs by collecting in one place a galaxy of experience and ability the likes of which even the State Department had never seen. Many of these later drifted away, but a core remained to create a tradition and eventually to take key jobs in a mature intelligence system of the kind the United States required for coping with twentieth century problems.

(5) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

Corcoran, ever the loyal soldier to Roosevelt, agreed to help and visited his old friends in the Senate, including Senators Burton Wheeler of Montana, Worth Clark of Montana, and Robert La Follette of Wisconsin. A few weeks later Corcoran reported to the president that while these men were opposed to involvement in Europe, he did not believe that a modest aid program to China would cause them serious concern.

After evaluating Corcoran's optimistic assessment, Roosevelt conveyed to him, again through Lauchlin Currie, that he wanted to establish a private corporation to provide assistance to the Chinese. Corcoran thought the president's idea was ingenious, and later wrote that "if we'd tried to set up a government corporation per se, or do the work out of a Federal office, there would have been devil to pay on the Hill." Instead, Corcoran set up a civilian corporation, which he chartered in Delaware and, at the suggestion of the president, named China Defense Supplies. It would be, as Corcoran later recalled, "the entire lend lease operation" for Asia.

In order to provide the company with the stamp of respectability, Roosevelt arranged for his elderly uncle, Frederick Delano, who'd spent a lifetime in the China trade, to be co-chairman. The other chairman was T. V. Soong, Chiang's personal representative who frequently visited Washington to lobby for aid to his government. Soong, a Harvard graduate, was also Chiang's finance minister, as well as his banker and his brother-in-law. And he was a close friend of David Corcoran, whom he had met when the younger Corcoran was working in the Far East.

After getting the green light to proceed with the establishment of China Defense Supplies, Corcoran hired a staff to run the company. With Delano and Soong as the chairmen, Corcoran went about appointing a politically savvy management team. First, he asked his brother David to take a leave of absence from Sterling to become president. Although David Corcoran was an extremely competent manager, Sterling was then under investigation by the Department of Justice, and David's appointment could be cynically viewed as an attempt by Tommy to protect his brother from the investigation by shielding him with a quasi-government role. Next he appointed a bright young lawyer named Bill Youngman as general counsel. Youngman had previously clerked for Judge Learned Hand, and after Ben Cohen recommended him, he landed a job as general counsel at the Federal Power Commission. To direct the program from China, Corcoran chose Whitey Willauer, who had been his brother Howard's roommate at Exeter, Princeton, and Harvard Law School. Corcoran had previously helped Willauer get a job at the Federal Aviation Administration and he knew Willauer was "crazy about China." After helping to establish and run China Defense Supplies, Willauer moved over to the Foreign Economic Administration, where he supervised both Lend-Lease to China and purchases from China. Lastly, Corcoran arranged for the Marine Corps to detail Quinn Shaughnessy, who, like Corcoran, was a graduate of Harvard Law School. Shaughnessy was given the task of locating and acquiring goods, supplies, and weapons For the Chinese. Corcoran took no title himself other than outside counsel for China Defense Supplies. He paid himself five thousand dollars to set up the company, but didn't want his affiliation with it to interfere with his incipient lobbying practice.

(6) William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963)

The shy, modest Cohen, a Jew from Muncie, Indiana, was a former Brandeis law clerk who had developed into a brilliant legislative draftsman. Corcoran, an Irishman from a Rhode Island mill town, had gone from Harvard Law School to Washington in 1926 to serve as secretary to Mr. Justice Holmes; Holmes found him "quite noisy, quite satisfactory, and quite noisy." Roosevelt had discovered Corcoran and Cohen, who had teamed up to draft Wall Street regulatory legislation, to be remarkably resourceful in resolving knotty governmental problems, and by the spring of 1935 "the boys," as Frankfurter called them, were playing key roles in the New Deal."

Corcoran was a new political type: the expert who not only drafted legislation but maneuvered it through the treacherous corridors of Capitol Hill. Two Washington reporters wrote of him: "He could play the accordion, sing any song you cared to mention, read Aeschylus in the original, quote Dante and Montaigne by the yard, tell an excellent story, write a great bill like the Securities Exchange Act, prepare a presidential speech, tread the labyrinthine maze of palace politics or chart the future course of a democracy with equal ease." He lived with Cohen and five other New Dealers in a house on R Street; as early as the spring of 1934, G.O.P. congressmen were learning to ignore the sponsors of New Deal legislation and level their attacks at "the scarlet-fever boys from the little red house in Georgetown."

In the first two years of the New Deal, the Brandeisians chafed as the NRA advocates sat at the President's right hand. They rejoiced only in the TVA, since it both checked monopoly and accentuated decentralization, and in the regulation of securities issues and the stock market, which marked the success of Brandeis' earlier crusade against the money power. Not until 1935 did the Brandeisians make their way. That year saw the triumph of the decentralizers in the fight over the social security bill, and the enhanced power in TVA of Frankfurter's follower, David Lilienthal. Brandeis himself had a direct hand

in the most important victory of all: the invalidation of the NRA.

(7) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

Corcoran had only been out of the government for a short time, but he was "running" the Asian Lend-Lease program and working to defend against both the Justice Department inquiry and a potential congressional investigation into Sterling Pharmaceutical. Corcoran assembled a defense team led by John Cahill, his former classmate at Harvard Law School and an associate of his at Cotton and Franklin. Cahill was the U.S. attorney in New York and, not coincidentally, had been working with Thurman Arnold, the assistant attorney general for antitrust matters, supervising the Department of justice's inquiry into Sterling. At Corcoran's urging, Cahill resigned his post on February 10, 1941, to enter private practice. There were no laws prohibiting him from representing a client in a case on which he had been working, and notwithstanding a clear conflict of interest, Cahill immediately began representing Sterling Pharmaceutical.

Now that he had help on the Sterling case, Corcoran began to take on new business. His first major client was Henry J. Kaiser, a West Coast businessman who had made a fortune from government contracts, primarily in helping build the Boulder and Shasta Dams. Corcoran had first met Kaiser when Corcoran was an attorney at the RFC and he, Harold Ickes, and David Lilienthal established the Bonneville Power Administration. Now as the country prepared for war, Kaiser recognized that the government's procurement program offered many exceptional business opportunities. Kaiser needed to know the people in Washington who were making the decisions, and he called on Tommy Corcoran for assistance.

Corcoran was able to open doors for Kaiser all over town. At the White House, Corcoran introduced him to several people, including Lauchlin Currie. At the Federal Reserve, Corcoran arranged a meeting with the chairman, Marriner Eccles, who had been introduced to Kaiser several years earlier when Eccles was a construction magnate in Utah. Corcoran later boasted that through his contacts at the Interior Department he denied the Bonneville Power Administration to Alcoa, the giant aluminum company, and helped secure it for Kaiser.

Corcoran also helped at the War Department, where he introduced Kaiser to William Knudsen, the former chief executive of General Motors who had been appointed at the end of 1940 to command the Office of Production Management to coordinate defense preparations. Over the course of the next few years, Kaiser arranged for $645 million in building contracts at his ten shipyards, eight of which were located on the West Coast. He netted a profit on each ship of between $60,000 to $110,000 and made millions with his assembly methods. He pioneered group medicine at his companies, creating what eventually became Kaiser Permanente, a precursor to today's health maintenance organizations.

(8) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

In late 1941 Johnson approached E. G. Kingsbery, an ultraconservative Austin businessman who owned a half interest in KTBC. Kingsbery had opposed Johnson's candidacy, but after the congressman helped Kingsbery's son gain admission to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, the businessman was indebted to him. Johnson told Kingsbery, "I'm not a newspaperman, not a lawyer, and I might get beat sometime. I did have a second-class teacher's certificate, but it's expired, and I want to get into some business." Impressed by Johnson's energy and initiative, Kingsbery told Johnson that he wanted to pay his "obligation" to him and simply gave him his half-interest option.

The option to buy the other half was owned by the Wesley West family, who had extensive holdings in the oil industry and owned the Austin Daily Tribune, a conservative daily. Just a day or two before Christmas, Johnson traveled to Plano County to work out a deal with Wesley West at his ranch. Johnson charmed the older man, who later recalled, "I didn't like Lyndon Johnson," but said after meeting him, "He's a pretty good fellow. I believe I'll sell it to him."

With the two half-interest options, Johnson had only one more obstacle to overcome in his purchase of the station - approval from the Federal Communications Commission. To help navigate the process, Johnson called Tommy Corcoran.

When Corcoran left government and had been looking for clients, Johnson made sure that he was placed on retainer by the Houston contracting firm of Brown and Root, owned by George and Herman Brown, who had financed Lyndon's previous campaigns. Corcoran had been paid as much as fifteen thousand dollars for "advice, conferences and negotiations" related to shipbuilding contracts. Now it was Johnson looking to Corcoran to help him with a business proposition. Corcoran did not disappoint. As Corcoran later told Johnson's biographer, Robert Caro, "I helped out all up and down the line."

Corcoran had an important contact at the FCC: James Fly, the chairman of the commission, had been his classmate at Harvard Law School and owed his appointment in good measure to Corcoran. Justice Frank Murphy later told Felix Frankfurter that he had helped get Fly the position as a favor to Tommy Corcoran. According to Murphy, "[It] was at Tom's request that I gave the former Chairman a ten thousand dollar a year job so as to create a vacancy into which Fly was placed."

(9) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

As planning for the U.S. plot progressed, Corcoran and other top officials at United Fruit became anxious about identifying a future leader who would establish favorable relations between the government and the company. Secretary of State Dulles moved to add a"civilian" adviser to the State Department team to help expedite Operation Success. Dulles chose a friend of Corcoran's, William Pawley, a Miami-based millionaire who, along with Corcoran, Chennault, and Willauer, had helped set up the Flying Tigers in the early r94os and then helped several years later to transform it into the CIA's airline, Civil Air Transport. Besides his association with Corcoran, Pawley's most important qualification for the job was that he had a long history of association with right-wing Latin American dictators.

CIA director Dulles had grown disillusioned with J. C. King and asked Colonel Albert Haney, the CIA station chief in Korea, to be the U.S. field commander for the operation. Haney enthusiastically accepted, although he was apparently unaware of the role that the United Fruit Company had played in his selection. Haney had been a colleague of King's, and though King was no longer directing the operation, he remained a member of the agency planning team. He suggested that Haney meet with Tom Corcoran to see about arming the insurgency force with the weapons that had been mothballed in a New York warehouse after the failed Operation Fortune. When the supremely confident Haney said he didn't need any help from a Washington lawyer, King rebuked him, "If you think you can run this operation without United Fruit, you're crazy!"

The close working relationship between the CIA and United Fruit was perhaps best epitomized by Allen Dulles's encouragement to the company to help select an expedition commander for the planned invasion. After the CIA's first choice was vetoed by the State Department, United Fruit proposed Corcova Cerna, a Guatemalan lawyer and coffee grower. Cerna had long worked for the company as a paid legal adviser, and even though Corcoran referred to him as "a liberal," he believed that Cerna would not interfere with the company's land holdings and operations. After Cerna was hospitalized with throat cancer, a third candidate, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, emerged as the compromise choice.

According to United Fruit's Thomas McCann, when the Central Intelligence Agency finally launched Operation Success in late June 1954, "United Fruit was involved at every level." From neighboring Honduras, Ambassador Willauer, Corcoran's former business partner, directed bombing raids on Guatemala City. McCann was told that the CIA even shipped down the weapons used in the uprising "in United Fruit boats."

On June 27, 1954, Colonel Armas Ousted the Arbenz government and ordered the arrest of all communist leaders in Guatemala. While the coup was successful, a dark chapter was opened in American support for right wing military dictators in Central America.

(10) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

In February 1960 the New York Times reported that while Senator Johnson "stubbornly contends that he has no plans, or expectations of becoming a candidate, several aides, including Corcoran, were working for him behind the scenes." The article quoted Corcoran as suggesting that he was used for "the testing of new ideas."

Three months earlier Corcoran's good friend, the seventy-eight-year old Speaker of the House, Sam Rayburn, had returned to his home state of Texas to announce the formation of an "unofficial Johnson for President campaign." Rayburn's announcement followed that of Senator John F. Kennedy, who had declared his candidacy for the presidency in the Senate caucus room a month earlier, and Senator Hubert Humphrey, who had tossed his hat into the ring at the beginning of the new year. Sensing that he had a greater name recognition than any of the declared candidates, and desperately seeking vindication after two stinging previous defeats, Adali Stevenson allowed others to present his case. Senator Stuart Symington had decided to wait in the wings, hoping that in a deadlocked convention he would become the consensus alternative.

Corcoran was one of a number of prominent New Dealer-era luminaries, including Eliot Janeway, Dean Acheson, and William O. Douglas, who were supporting Lyndon Johnson. Presidential chronicler Theodore White later called the group "a loose and highly ineffective coalition," which was not entirely fair since it did manage to raise nearly $150,000 for Johnson's undeclared candidacy. LBJ himself decided not to campaign actively; as majority leader he believed he couldn't neglect his Senate duties to mount a full-scale campaign.

(11) David McKean, Peddling Influence (2004)

In late 1964, however, Corcoran was preoccupied with a political scandal. Only weeks after Johnson was sworn in as president, Bobby Baker got into trouble for fraud and tax evasion. Baker had been LBJ's closest aide and most important adviser in the Senate. He and Corcoran had known each other for many years, and although never close friends, their mutual respect for Lyndon Johnson and the fact that they were both political operators meant that they saw one another often.

Tommy had actually helped Baker buy his house in the affluent section of Washington known as Spring Valley. Corcoran had learned that Baker and his wife, who was expecting their third child, were looking for a larger home. At the time, Tommy was representing Tenneco, and he knew that a house under construction - originally intended for one of the company's vice presidents, who had been recalled to Texas - was slated to go on the market for $175,000. Baker was encouraged to put in a bid of $125,000, which was accepted. Although Baker never recalled doing any special favor for Corcoran in return, Tommy always knew that he was owed one.

In January 1964 Baker was indicted by the U.S. attorney in Washington for tax evasion. The former Capitol Hill aide sought out John Lane, whom he had known in the Senate and who by now had established a small but highly regarded law practice. Lane did not have a white-collar defense practice, but he knew that Tommy Corcoran's brother, Howard, practiced in New York with Boris Kostelanitz, a respected attorney who had handled several criminal tax cases. Lane and Baker went to see Corcoran in his office. As they sat and talked on Corcoran's leather couch, Corcoran's secretary came in and told Baker that Attorney General Robert Kennedy was on the telephone. Kennedy wanted to assure Baker that he had not personally ordered the case against him and that his knowledge of the case came only from newspaper clippings.

Baker retained Kostelanitz to defend him on the charges of tax evasion and retained Edward Bennett Williams, the renowned criminal lawyer, as his counsel. The case was assigned to judge Oliver Gasch of the district court after several judges reportedly rejected it because they personally knew Baker. Ironically, Gasch, a close friend of Howard Corcoran's, owed his appointment to Tommy Corcoran. But much to Baker's chagrin, Corcoran didn't intercede on his behalf, probably because Lyndon Johnson never asked him. The president, according to one lawyer close to the case, "didn't want to touch Baker with a ten foot pole."