Nagasaki

In 1942 the Manhattan Engineer Project was set up in the United States under the command of Brigadier General Leslie Groves. Scientists recruited to produce an atom bomb included Robert Oppenheimer (USA), David Bohm (USA), Leo Szilard (Hungary), Eugene Wigner (Hungary), Rudolf Peierls (Germany), Otto Frisch (Germany), Niels Bohr (Denmark), Felix Bloch (Switzerland), James Franck (Germany), James Chadwick (Britain), Emilio Segre (Italy), Enrico Fermi (Italy), Klaus Fuchs (Germany) and Edward Teller (Hungary).

Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were deeply concerned about the possibility that Germany would produce the atom bomb before the allies. At a conference held in Quebec in August, 1943, it was decided to try and disrupt the German nuclear programme. In February 1943, SOE saboteurs successfully planted a bomb in the Rjukan nitrates factory in Norway. As soon as it was rebuilt it was destroyed by 150 US bombers in November, 1943. Two months later the Norwegian resistance managed to sink a German boat carrying vital supplies for its nuclear programme.

Meanwhile the scientists working on the Manhattan Project were developing atom bombs using uranium and plutonium. The first three completed bombs were successfully tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16th July, 1945. James Chadwick later described what he saw during the test: "An intense pinpoint of light which grew rapidly to a great ball. Looking sideways, I could see that the hills and desert around us were bathed in radiance, as if the sun had been turned on by a switch. The light began to diminish but, peeping round my dark glass, the ball of fire was still blindingly bright ... The ball had then turned through orange to red and was surrounded by a purple luminosity. It was connected to the ground by a short grey stem, resembling a mushroom."

By the time the atom bomb was ready to be used Germany had surrendered. James Franck and Leo Szilard drafted a petition signed by just under 70 scientists opposed to the use of the bomb on moral grounds. Franck pointed out in his letter to Truman: "The military advantages and the saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and by a wave of horror and repulsion sweeping over the rest of the world and perhaps even dividing public opinion at home. From this point of view, a demonstration of the new weapon might best be made, before the yes of representatives of all the United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America could say to the world, "You see what sort of a weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future if other nations join us-in this renunciation and agree to the establishment of an efficient international control."

However, the advice of the scientists was ignored by Harry S. Truman, the USA's new president, and he decided to use the bomb on Japan. General Dwight Eisenhower agreed with the scientists: "I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of face."

At Yalta, the Allies had attempted to persuade Joseph Stalin to join in the war with Japan. By the time the Potsdam meeting took place, they were having doubts about this strategy. Winston Churchill in particular, were afraid that Soviet involvement would lead to an increase in their influence over countries in the Far East. On 17th July 1945 Stalin announced that he intended to enter the war against Japan.

President Truman now insisted that the bomb should be used before the Red Army joined the war against Japan. Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, wanted the target to be Kyoto because as it had been untouched during previous attacks, the dropping of the atom bomb on it would show the destructive power of the new weapon. However, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, argued strongly against this as Kyoto was Japan's ancient capital, a city of immense religious, historical and cultural significance. General Henry Arnold supported Stimson and Truman eventually backed down on this issue.

President Truman wrote in his journal on 25th July, 1945: "This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Secretary of War, Mr Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we, as leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new. He & I are in accord. The target will be a purely military."

Truman's military advisers accepted that Kyoto would not be targeted but insisted that another built-up area should be chosen instead: "While the bombs should not concentrate on civilian areas, they should seek to make a profound a psychological impression as possible. The most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers' houses."

Winston Churchill insisted that two British representives should witness the dropping of the atom bomb. Squadron Leader Leonard Cheshire and William Penny, a scientist working on the Manhattan Project, were chosen for this task. Churchill ordered them to learn "about the taqctical aspects of using such a weapon, reach a conclusion about its future implications for air warfare and report back to the Prime Minister."

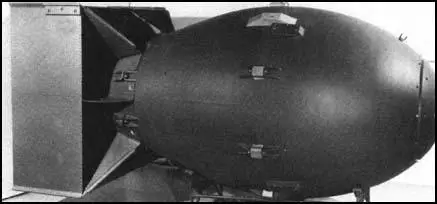

General Thomas Farrell, Commander of the Manhattan Project, explained to Cheshire and Penny that they had produced two types of bomb. Fat Man relied upon implosion: a 12 lb sphere of plutonium would be abruptly squeezed to super-critically by the detonation of an envelope of explosive. Little Boy functioned by a gun mechanism which fired two subcritical masses of uranium 235 together.

President Harry S. Truman eventually decided that the bomb should be dropped on Hiroshima. It was the largest city in the Japanese homeland (except Kyoto) which remained undamaged, and a place of military industry. However, Truman, after listening from advice of General Curtis LeMay, refused permission for Leonard Cheshire and William Penny to witness the event. Leslie Groves, according to Cheshire, "said firmly that there was no room for either of us; in any case he couldn't see why we needed to be there, for we would receive a full written report and could ask to see any documentation we wanted."

On 6th August 1945, a B29 bomber piloted by Paul Tibbets, dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. Michihiko Hachiya was living in the city at the time: "Hundreds of people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags or a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they stopped. I found them lying so thick on both sides of the road that it was impossible to pass without stepping on them."

Later that day President Harry S. Truman made a speech where he argued: "The harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been used against those who brought war to the Far East. We have spent $2,000,000,000 (about $500,000,000) on the greatest gamble in history, and we have won. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development."

Truman then issued a warning to the Japanese government: "We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake, we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued from Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of run from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with a fighting skill of which they have already become well aware."

Hideki Tojo, Japan's Foreign Minister, told Emperor Hirohito on 8th August, 1945, that Hiroshima had been obliterated by an atom bomb and advised surrender. Others raised doubts about whether the United States had more than one of these bombs. The Supreme Council decided to convene a meeting on the morning of 9th August. As they had not immediately surrendered President Truman ordered that a second atom bomb should be dropped on Japan.

Major Charles Sweeney was selected to lead the mission and Nagasaki was chosen as the target. This time it was agreed that Leonard Cheshire and William Penny, could travel on the aircraft that was to take photographs of the attack on 9th August. When they reached Nagasaki they found the city covered in cloud and Kermit Beahan, the bombardier, was at first unable to find the target. Eventually, the cloud parted and Beahan dropped the bomb a mile and a half from the intended aiming point.

William Laurence was a journalist who was invited by Leslie Groves to be on Sweeney's aircraft: "We watched a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shoot up like a meteor coming from the earth instead of outer space. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born before our incredulous eyes. Even as we watched, a ground mushroom came shooting out of the top to 45,000 feet, a mushroom top that was even more alive than the pillar, seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam, a thousand geysers rolled into one. It kept struggling in elemental fury, like a creature in the act of breaking the bonds that held it down. When we last saw it, it had changed into a flower-like form, its giant petals curving downwards, creamy-white outside, rose-coloured inside. The boiling pillar had become a giant mountain of jumbled rainbows. Much living substance had gone into those rainbows."

Leonard Cheshire later recalled in his book, The Light of Many Suns (1985): "The ultra-dark glasses we each had round our foreheads to protect our eyes from the blinding light of the bomb were not needed because we were about fifty miles away. By the time I saw it, the flash had turned into a vast fire-ball which slowly became dense smoke, 2,000 feet above the ground, half a mile in diameter and rocketing upwards at the rate of something like 20,000 feet a minute. I was overcome, not by its size, nor by its speed of ascent but by what appeared to me its perfect and faultless symmetry. In this it was unique, above every explosion that I had ever heard of or seen, the more frightening because it gave the impression of having its immense power under full and deadly control.... The cloud lifted itself to 60,000 feet where it remained stationary, a good two miles in diameter, sulphurous and boiling. Beneath it, stretching right down to the ground was a revolving column of yellow smoke, fanning out at the bottom to a dark pyramid, wider at its base than was the cloud at its climax. The darkness of the pyramid was due to dirt and dust which one could see being sucked up by the heat. All around it, extending perhaps another mile, were springing up a mass of separate fires. I wondered what could have caused them all."

Fumiko Miura was a 16 year-old girl working in Nagasaki at the time: "I was doing some clerical work for the Japanese imperial army. At about 11 o'clock, I thought I heard the throbs of a B-29 circling over the two-storey army headquarters building. I wondered why an American bomber was flying around above us when we had been given the all-clear.... At that moment, a horrible flash, thousands of times as powerful as lightning, hit me. I felt that it almost rooted out my eyes. Thinking that a huge bomb had exploded above our building, I jumped up from my seat and was hit by a tremendous wind, which smashed down windows, doors, ceilings and walls, and shook the whole building. I remember trying to run for the stairs before being knocked to the floor and losing consciousness. It was a hot blast, carrying splinters of glass and concrete debris. But it did not have that burning heat of the hypocentre, where everyone and everything was melted in an instant by the heat flash. I learned later that the heat decreased with distance. I was 2,800m away from the hypocentre."

After a long debate Emperor Hirohito intervened and said he could no longer bear to see his people suffer in this way. On 15th August the people of Japan heard the Emperor's voice for the first time when he announced the unconditional surrender and the end of the war. Naruhiko Higashikuni was appointed as head of the surrender government.

Primary Sources

(1) This article by William Laurence about the bombing Nagasaki appeared in several newspapers in August 1945.

We are on our way to bomb the mainland of Japan. Our flying contingent consists of three specially designed B-29 Superforts, and two of these carry no bombs. But our lead plane is on its way with another atomic bomb, the second in three days, concentrating its active substance, and explosive energy equivalent to 20,000, and under favorable conditions, 40,000 tons of TNT.

We have several chosen targets. One of these is the great industrial and shipping center of Nagasaki, on the western shore of Kyushu, one of the main islands of the Japanese homeland.

I watched the assembly of this man-made meteor during the past two days, and was among the small group of scientists and Army and Navy representatives privileged to be present at the ritual of its loading in the Superfort last night, against a background of threatening black skies torn open at intervals by great lightning flashes.

It is a thing of beauty to behold, this "gadget." In its design went millions of man-hours of what is without a doubt the most concentrated intellectual effort in history. Never before had so much brain-power been focused on a single problem.

This atomic bomb is different from the bomb used three days ago with such devastating results on Hiroshima.

I saw the atomic substance before it was placed inside the bomb. By itself it is not at all dangerous to handle. It is only under certain conditions, produced in the bomb assembly, that it can be made to yield up its energy, and even then it gives up only a small fraction of its total contents, a fraction, however, large enough to produce the greatest explosion on earth.

The briefing at midnight revealed the extreme care and the tremendous amount of preparation that had been made to take care of every detail of the mission, in order to make certain that the atomic bomb fully served the purpose for which it was intended. Each target in turn was shown in detailed maps and in aerial photographs. Every detail of the course was rehearsed, navigation, altitude, weather, where to land in emergencies. It came out that the Navy had submarines and rescue craft, known as "Dumbos" and "Super Dumbos," stationed at various strategic points in the vicinity of the targets, ready to rescue the fliers in case they were forced to bail out.

The briefing period ended with a moving prayer by the Chaplain. We then proceeded to the mess hall for the traditional early morning breakfast before departure on a bombing mission.

A convoy of trucks took us to the supply building for the special equipment carried on combat missions. This included the "Mae West," a parachute, a life boat, an oxygen mask, a flak suit and a survival vest. We still had a few hours before take-off time but we all went to the flying field and stood around in little groups or sat in jeeps talking rather casually about our mission to the Empire, as the Japanese home islands are known hereabouts.

In command of our mission is Major Charles W. Sweeney, 25, of 124 Hamilton Avenue, North Quincy, Massachusetts. His flagship, carrying the atomic bomb, is named "The Great Artiste," but the name does not appear on the body of the great silver ship, with its unusually long, four-bladed, orange-tipped propellers. Instead it carried the number "77," and someone remarks that it is "Red" Grange's winning number on the Gridiron.

Major Sweeney's co-pilot is First Lieutenant Charles D. Albury, 24, of 252 Northwest Fourth Street, Miami, Florida. The bombardier upon whose shoulders rests the responsibility of depositing the atomic bomb square on its target, is Captain Kermit K. Beahan, of 1004 Telephone Road, Houston, Texas, who is celebrating his twenty-seventh birthday today.

Captain Beahan has been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and one Silver Oak Leaf Cluster, the Purple Heart, the Western Hemisphere Ribbon, the European Theater ribbon and two battle stars. He participated in the first heavy bombardment mission against Germany from England on August 17, 1942, and was on the plane that transported General Eisenhower from Gibraltar to Oran at the beginning of the North African invasion. He has had a number of hair-raising escapes in combat.

(2) Leonard Cheshire, The Light of Many Suns (1985)

At 08.00 a warning light on the black box in Sweeney's aircraft indicated a fault in the bomb. It was far too late to start testing all the circuits, and Ashworth made an intuitive guess; he found and repaired the faulty switches. But Sweeney now had an additional worry. He had done two runs onto Kokura from opposite points of the compass without managing a visual, and when his flight engineer reported the fuel level as dangerously low, he left for Nagasaki, telling his bomb-aimer, Captain Beahan, that they could only afford one run and if there was no visual sighting it would have to be a no drop. The weather on the approach run was even worse than Kokura, and it began to dawn on Sweeney that with no fuel latitude he would have to fly a direct course to Okinawa, the nearest emergency landing field, and jettison the bomb over the first open stretch of sea that was clear of shipping. At 10.00, with the city still visible only on radar, Beahan suddenly shouted: "I've got it. I see the city. I'll take it now." One minute later, at 11.01, the bomb dropped, Sweeney went into a rate-four turn to get as far away as possible from the shock waves, and Bock, flying behind him, dropped the instrument capsule in which was Alvarez' record message to Sagani.

For the past twenty minutes we had been staring intently around us looking for the explosion and wondering what on earth could have happened to Sweeney. All we saw was smoke coming from a town, the result of a medium bomber raid, until there was a cry on the intercom and to port we saw a gigantic plume of billowing white smoke. "Yes, that's it," I shouted, but I was wrong; it was an incendiary attack on a town of mostly wooden houses. Quite what warned us I am not certain - I think perhaps a fleeting flash - but we all seemed to know as if by instinct, for there was a simultaneous cry and Hopkins swung the nose round to starboard and into line with the flash of light. The ultra-dark glasses we each had round our foreheads to protect our eyes from the blinding light of the bomb were not needed because we were about fifty miles away. By the time I saw it, the flash had turned into a vast fire-ball which slowly became dense smoke, 2,000 feet above the ground, half a mile in diameter and rocketing upwards at the rate of something like 20,000 feet a minute. I was overcome, not by its size, nor by its speed of ascent but by what appeared to me its perfect and faultless symmetry. In this it was unique, above every explosion that I had ever heard of or seen, the more frightening because it gave the impression of having its immense power under full and deadly control. "Against me", it seemed to declare, "you cannot fight." My whole being felt overwhelmed, first by a tidal wave of relief and hope - it's all over! - then by a revolt against using such a weapon. But, I remembered, I had been sent here for a purpose and as best I could I must get on with my job. The cloud lifted itself to 60,000 feet where it remained stationary, a good two miles in diameter, sulphurous and boiling. Beneath it, stretching right down to the ground was a revolving column of yellow smoke, fanning out at the bottom to a dark pyramid, wider at its base than was the cloud at its climax. The darkness of the pyramid was due to dirt and dust which one could see being sucked up by the heat. All around it, extending perhaps another mile, were springing up a mass of separate fires. I wondered what could have caused them all....

We were a silent crew on our way home. I thanked Hopkins for the courtesy of a cockpit seat, and wriggled my way down the tunnel to join Bill in the central compartment. He startled me by suddenly saying: "That's only the detonator compared with the bomb that is to come." He meant the hydrogen bomb, but I asked no questions, because it was beyond my comprehension. Foremost in my mind was a growing conviction that Sweeney had missed the aiming point by two miles or more. I wondered how this could have happened with a crew that had been consistently averaging a 200-yard error from 30,000 feet, but I did not yet know the pressures under which Sweeney had been operating. He had left the target immediately after dropping the bomb and crossed the Okinawa coast with one engine dead through lack of fuel. His mayday call for an emergency landing was refused - as happened to me in precisely the same predicament over Linton-on-Ouse in 1941 coming back from Berlin - so he fired all his distress flares and kept coming in on his approach. At dispersal point they found less than 10 gallons in his wing tanks, apart from the 600 he could not use in the bomb bay. It was 12.30. His co-pilot, Lieutenant Charles Albury, went to the chapel and prayed that what they had just done would put an end to the killing.

(3) William Laurence, Dawn Over Zero (1946)

We watched a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shoot up like a meteor coming from the earth instead of outer space. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born before our incredulous eyes. Even as we watched, a ground mushroom came shooting out of the top to 45,000 feet, a mushroom top that was even more alive than the pillar, seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam, a thousand geysers rolled into one. It kept struggling in elemental fury, like a creature in the act of breaking the bonds that held it down. When we last saw it, it had changed into a flower-like form, its giant petals curving downwards, creamy-white outside, rose-coloured inside. The boiling pillar had become a giant mountain of jumbled rainbows. Much living substance had gone into those rainbows.

(4) Fumiko Miura was a 16 year old girl working in Nagasaki when the bomb was dropped on 6th August 1945. She wrote about this in her book Pages from the Seasons.

I was doing some clerical work for the Japanese imperial army. At about 11 o'clock, I thought I heard the throbs of a B-29 circling over the two-storey army headquarters building. I wondered why an American bomber was flying around above us when we had been given the all-clear. There was no noise of anti-aircraft fire. We were working in our shirt sleeves; and all the windows and doors were wide open because it was so stiflingly hot and humid in our two-storey building.

At that moment, a horrible flash, thousands of times as powerful as lightning, hit me. I felt that it almost rooted out my eyes. Thinking that a huge bomb had exploded above our building, I jumped up from my seat and was hit by a tremendous wind, which smashed down windows, doors, ceilings and walls, and shook the whole building. I remember trying to run for the stairs before being knocked to the floor and losing consciousness. It was a hot blast, carrying splinters of glass and concrete debris. But it did not have that burning heat of the hypocentre, where everyone and everything was melted in an instant by the heat flash. I learned later that the heat decreased with distance. I was 2,800m away from the hypocentre.

When I came to, it was evening. I was lying in the front yard of the headquarters - I still do not know how I got there - covered with countless splinters of glass, wood and concrete, and losing blood from both arms. I felt dull pains all over my body. My white short-sleeved blouse and mompe (the authorities ordered women, young and old, to wear these Japanese-style loose trousers) were torn and bloody. I felt strangely calm. I looked down at my wrist watch; it was completely broken.

With no detailed information about the "new type of bomb" issued by the government, we did not know for about a week that it was actually the atomic bomb. We learned that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan on the day of the Nagasaki atomic bombing. I was infuriated at our government, which still urged us to fight against the allied forces. We were injured, and suffering from a strange weakness with no adequate treatment. Food, clothes, information: everything was in shortage. Yet the government still shouted its slogan: "Ichioku gyokusai!" ("100 million people should meet honourable deaths; never surrender!") Who did the Japanese government exist for, I wondered?

Shortly after the explosion, many survivors noticed in themselves a strange illness: vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhoea, high fever, weakness, purple spots on various parts of the body, bleeding from the mouth, gums, and throat, the falling-out of hair, and a very low white blood cell count. We called the illness "atomic bomb disease", and many of those who were only superficially injured died soon or months after. The lack of medical supplies and information about the after-effects of atomic radiation made it impossible to provide us with adequate treatment. First aid was all we could get.

Decades afterwards, I had a series of operations for cancer, which may be attributable to my having been exposed to radiation. However, I am not yet destroyed. With the blessing of gods and Buddha, I have been allowed to live. For the sake of those who were killed without mercy during and after the Nagasaki atomic bombing, and also for myself, I want to be able to survive for many more years. My physical being may be transient, but I believe that my spiritual being can remain undefeated. I wish sincerely that human beings will become wise enough to abandon all forms of nuclear weapons in the near future.