The Atom Bomb

Just before the First World War two German scientists, James Franck and Gustav Hertz carried out experiments where they bombarded mercury atoms with electrons and traced the energy changes that resulted from the collisions. Their experiments helped to substantiate the theory put forward by Nils Bohr that an atom can absorb internal energy only in precise and definite amounts.

In 1921 two Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner, discovered nuclear isomers. Over the next few years they devoted their time to researching the application of radioactive methods to chemical problems.

In the 1930s they became interested in the research being carried out by Enrico Fermi and Emilio Segre at the University of Rome. This included experiments where elements such as uranium were bombarded with neutrons. By 1935 the two men had discovered slow neutrons, which have properties important to the operation of nuclear reactors.

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner were now joined by Fritz Strassmann and discovered that uranium nuclei split when bombarded with neutrons. In 1938 Meitner, like other Jews in Nazi Germany, was dismissed from her university post. She moved to Sweden and later that year she wrote a paper on nuclear fission with her nephew, Otto Frisch, where they argued that by splitting the atom it was possible to use a few pounds of uranium to create the explosive and destructive power of many thousands of pounds of dynamite.

In January, 1939 a Physics Conference took place in Washington in the United States. A great deal of discussion concerned the possibility of producing an atomic bomb. Some scientists argued that the technical problems involved in producing such a bomb were too difficult to overcome, but the one thing they were agreed upon was that if such a weapon was developed, it would give the country that possessed it the power to blackmail the rest of the world. Several scientists at the conference took the view that it was vitally important that all information on atomic power should be readily available to all nations to stop this happening.

On 2nd August, 1939, three Jewish scientists who had fled to the United States from Europe, Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner, wrote a joint letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, about the developments that had been taking place in nuclear physics. They warned Roosevelt that scientists in Germany were working on the possibility of using uranium to produce nuclear weapons.

Roosevelt responded by setting up a scientific advisory committee to investigate the matter. He also had talks with the British government about ways of sabotaging the German efforts to produce nuclear weapons.

In May, 1940, Germany invaded Denmark, the home of Niels Bohr, the world's leading expert on atomic research. It was feared that he would be forced to work for Nazi Germany. With the help of the British Secret Service he escaped to Sweden before being moving to the United States.

In 1942 the Manhattan Engineer Project was set up in the United States under the command of Brigadier General Leslie Groves. Scientists recruited to produce an atom bomb included Robert Oppenheimer (USA), David Bohm (USA), Leo Szilard (Hungary), Eugene Wigner (Hungary), Rudolf Peierls (Germany), Otto Frisch (Germany), Felix Bloch (Switzerland), Niels Bohr (Denmark), James Franck (Germany), James Chadwick (Britain), Emilio Segre (Italy), Enrico Fermi (Italy), Klaus Fuchs (Germany) and Edward Teller (Hungary).

Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were deeply concerned about the possibility that Germany would produce the atom bomb before the allies. At a conference held in Quebec in August, 1943, it was decided to try and disrupt the German nuclear programme.

In February 1943, SOE saboteurs successfully planted a bomb in the Rjukan nitrates factory in Norway. As soon as it was rebuilt it was destroyed by 150 US bombers in November, 1943. Two months later the Norwegian resistance managed to sink a German boat carrying vital supplies for its nuclear programme.

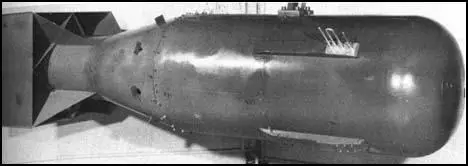

Meanwhile the scientists working on the Manhattan Project were developing atom bombs using uranium and plutonium. The first three completed bombs were successfully tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16th July, 1945.

By the time the atom bomb was ready to be used Germany had surrendered. Leo Szilard and James Franck circulated a petition among the scientists opposing the use of the bomb on moral grounds. However, the advice was ignored by Harry S. Truman, the USA's new president, and he decided to use the bomb on Japan.

On 6th August 1945, a B29 bomber dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. It has been estimated that over the years around 200,000 people have died as a result of this bomb being dropped. Japan did not surrender immediately and a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. On 10th August the Japanese surrendered. The Second World War was over.

Primary Sources

(1) Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, Uranium Fission (1938)

From chemical evidence, Hahn and Strassmann conclude that radioactive barium nuclei (atom number Z = 56) are produced when uranium (Z = 92) is bombarded by neutrons. it has been pointed out that this might be explained as a result of a "fission" of the uranium nucleus, similar to the division of a droplet into two. The energy liberated in such processes was estimated to be about 200 Mev, both from mass defect considerations and from the repulsion of the two nuclei resulting from the "fission" process.

If this picture is correct, one would expect fast-moving nuclei of atomic number 40 to 50 and atomic weight 100 to 150, and up to 100 Mev energy, to emerge from a layer of uranium bombarded with neutrons. In spite of their high energy, these nuclei should have a range in air of a few millimeters only, on account of their high effective charge (estimated to be about 20), which implies very dense ionization. Each such particle should produce a total of about 3 million ion pairs.

By means of a uranium-lined ionization chamber, connected to a linear amplifier, I have succeeded in demonstrating the occurrence of such bursts of ionization. The amplifier was connected to a thyratron which was biased so as to count only pulses corresponding to at least 5 x 105 ion pairs. About 15 particles per minute were recorded when 300 milligram of radium, mixed with beryllium, was placed one centimeter from the uranium lining. No pulses at all were recorded during repeated check runs of several hours total duration when either the neutron source or the uranium lining was removed. With the neutron source at a distance of four centimeters from the uranium lining, surrounding the source with paraffin wax enhanced the effect by a factor of two.

It was checked that the number of pulses depended linearly on the strength of the neutron source; this was done in order to exclude the possibility that the pulses are produced by accidental summation of smaller pulses. When the amplifier was connected to an oscillograph, the large pulses could be seen very distinctly on the background of much smaller pulses due to the alpha particles of uranium.

By varying the bias of the thyratron, the maximum size of pulses was found to correspond to at least 2 million ion pairs, or an energy loss of 70 Mev of the particle within the chamber. Since the longest path of a particle in the chamber was 3 centimeters, and the chamber was filled with hydrogen at atmospheric pressure, the particles must ionize so heavily that they can make 2 million ion pairs on a path equivalent to 0.8 cm of air or less. From this it can be estimated that the ionizing particles must have an atomic weight of at least about seventy, assuming a reasonable connection between atomic weight and effective charge. This seems to be conclusive physical evidence for the breaking up of uranium nuclei into parts of comparable size, as indicated by the experiments of Hahn and Strassmann.

Experiments with thorium instead of uranium gave quite similar results, except that surrounding the neutron source with paraffin did not enhance, but slightly diminished the effect. This gives evidence in favor of the suggestion that also in the case of thorium some, if not all of the activities produced by neutron bombardment, should be ascribed to light elements. it should be remembered that no enhancement by paraffin has been found for the activities produced in thorium, except for one which is isotopic with thorium and is almost certainly produced by simple capture of the neutron.

Meitner has suggested another interesting experiment. If a metal plate is placed close to a uranium layer bombarded with neutrons, one would expect an active deposit of the light atoms emitted in the "fission" of the uranium to form on the plate. We hope to carry out such experiments, using the powerful source of neutrons which our high-tension apparatus will soon be able to provide.

(2) Conversation between William Stephenson and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (February, 1943)

Roosevelt: "Could Bohr be whisked out from under Nazi noses and brought to the Manhattan Project?"

Stephenson: "It will have to be a British mission. Niels Bohr is a stubborn pacifist. He does not believe his work in Copenhagen will benefit the Germany military caste. Nor is he likely to join an American enterprise which has as its sole objective the construction of a bomb. But he is in constant touch with old colleagues in England whose integrity he respects."

(3) Niels Bohr, letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt (3rd July, 1944)

A weapon of an unparalleled power is being created which will completely change all future conditions of warfare. Unless some agreement about the control of the use of the new active materials can be obtained in due time, any temporary advantage, however great, may be outweighed by a perpetual menace to human security. An initiative, aiming at forestalling a fateful competition, should serve to uproot any cause of distrust between the powers of whose harmonious collaboration the fate of coming generations will depend.

(4) Winston Churchill was completely opposed to the idea of sharing nuclear secrets with other countries. This was reflected in an internal memo he wrote on 25th March, 1945.

You may be quite sure that any power that gets hold of the secret will try to make the article and that this touches the existence of human society. The matter is out of all relation to anything else that exists in the world, and I could not think of participating in any disclosure to third or fourth parties at the present time. I do not believe there is anyone in the world who can possibly have reached the position now occupied by us and the United States.

(5) General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, told President Harry S. Truman that he was opposed to the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan.

I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of "face".

(6) William Leahy, chief of staff to the commander in chief of the United States, was opposed to the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan. He wrote about this in his autobiography, I Was There (1950)

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

It was my reaction that the scientists and others wanted to make this test because of the vast sums that had been spent on the project. Truman knew that, and so did the other people involved. However, the Chief Executive made a decision to use the bomb on two cities in Japan. We had only produced

two bombs at that time. We did not know which cities would be the targets, but the President specified that the bombs should be used against military facilities.

The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that, in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children. We were the first to have this weapon in our possession, and the first to use it. There is a practical certainty that potential enemies will develop it in the future and that atomic bombs will some time be used against us.

(7) Philip Morrison, a scientist, worked on the Manhattan Project at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Studs Terkel interviewed Morrison about his experiences during the Second World War for his book, The Good War (1985)

We spent a lot of time and risked a lot of lives to do so. Of my little group of eight, two were killed. We were using high explosives and radioactive material in large quantities for the first time. There was a series of events that rocked us. We were working hard, day and night, to do something that had never been done before. It might not work at all. I remember working late one night with my friend Louis Slotin. He was killed by a radiation accident. We shared the job. It could

have been I. But it was he, who was there that day.

James Franck, a truly wonderful man, produced the Franck Report: Don't drop the bomb on a city. Drop it as a demonstration and offer a warning. This was about a month before Hiroshima. The movement against the bomb was beginning among the physicists, but with little hope. It was strong at Chicago, but it didn't affect Los Alamos.

We heard the news of Hiroshima from the airplane itself, a coded message. When they returned, we didn't see them. The generals had them. But then the people came back with photographs. I remember looking at them with awe and terror. We knew a terrible thing had been unleashed. The men had a great party that night to celebrate, but we didn't go. Almost no physicists went to it. We obviously killed a hundred thousand people and that was nothing to have a party about. The reality confronts you with things you could never anticipate.

Before I went to Wendover, an English physicist. Bill Penney, held a seminar five days after the test at Los Alamos. He applied his calculations. He predicted that this would reduce a city of three or four hundred thousand people to nothing but a sink for disaster relief, bandages, and hospitals. He made it absolutely clear in numbers. It was reality. We knew it, but we didn't see it. As soon as the bombs were dropped, the scientists, with few exceptions, felt the time had come to end all wars.

(8) Henry Stimson, Secretary of War, letter to President Harry S. Truman (11th September, 1945)

The chief lesson I have learned in a long life is that the only way you can make a man trustworthy is to trust him; and the surest way to make him untrustworthy is to distrust him. If the atomic bomb were merely another, though more devastating, military weapon to be assimilated into our pattern of international relations, it would be one thing. We would then follow the old custom of secrecy and nationalistic military superiority relying on international caution to prescribe the future use of the weapon as we did with gas. But I think the bomb instead constitutes merely a first step in a new control by man over the forces of nature too revolutionary and dangerous to fit into old concepts. My idea of an approach to the Soviets would be a direct proposal after discussion with the British that we would be prepared in effect to enter an agreement with the Russians, the general purpose of which would be to control and limit the use of the atomic bomb as an instrument of war.

(9) John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946)

Dr. Sasaki and his colleagues at the Red Cross Hospital watched the unprecedented disease unfold and at last evolved a theory about its nature. It had, they decided, three stages. The first stage had been all over before the doctors even knew they were dealing with a new sickness; it was the direct reaction to the bombardment of the body, at the moment when the bomb went off, by neutrons, beta particles, and gamma rays. The apparently uninjured people who had died so mysteriously in the first few hours or days had succumbed in this first stage. It killed ninety-five per cent of the people within a half-mile of the center, and many thousands who were farther away. The doctors realized in retrospect that even though most of these dead had also suffered from burns and blast effects, they had absorbed enough radiation to kill them. The rays simply destroyed body cells– caused their nuclei to degenerate and broke their walls. Many people who did not die right away came down with nausea, headache, diarrhea, malaise, and fever, which lasted several days. Doctors could not be certain whether some of these symptoms were the result of radiation or nervous shock. The second stage set in ten or fifteen days after the bombing. Its first symptom was falling hair. Diarrhea and fever, which in some cases went as high as 106, came next. Twenty-five to thirty days after the explosion, blood disorders appeared: gums bled, the white-blood-cell count dropped sharply, and petechiae [eruptions] appeared on the skin and mucous membranes. The drop in the number of white blood corpuscles reduced the patient's capacity to resist infection, so open wounds were unusually slow in healing and many of the sick developed sore throats and mouths. The two key symptoms, on which the doctors came to base their prognosis, were fever and the lowered white-corpuscle count. If fever remained steady and high, the patient's chances for survival were poor. The white count almost always dropped below four thousand; a patient whose count fell below one thousand had little hope of living. Toward the end of the second stage, if the patient survived, anemia, or a drop in the red blood count, also set in. The third stage was the reaction that came when the body struggled to compensate for its ills–when, for instance, the white count not only returned to normal but increased to much higher than normal levels. In this stage, many patients died of complications, such as infections in the chest cavity. Most burns healed with deep layers of pink, rubbery scar tissue, known as keloid tumors. The duration of the disease varied, depending on the patient's constitution and the amount of radiation he had received. Some victims recovered in a week; with others the disease dragged on for months.

As the symptoms revealed themselves, it became clear that many of them resembled the effects of overdoses of X-ray, and the doctors based their therapy on that likeness. They gave victims liver extract, blood transfusions, and vitamins, especially Bl. The shortage of supplies and instruments hampered them. Allied doctors who came in after the surrender found plasma and penicillin very effective. Since the blood disorders were, in the long run, the predominant factor in the disease, some of the Japanese doctors evolved a theory as to the seat of the delayed sickness. They thought that perhaps gamma rays, entering the body at the time of the explosion, made the phosphorus in the victims' bones radioactive, and that they in turn emitted beta particles, which, though they could not penetrate far through flesh, could enter the bone marrow, where blood is manufactured, and gradually tear it down. Whatever its source, the disease had some baffling quirks. Not all the patients exhibited all the main symptoms. People who suffered flash burns were protected, to a considerable extent, from radiation sickness. Those who had lain quietly for days or even hours after the bombing were much less liable to get sick than those who had been active. Gray hair seldom fell out. And, as if nature were protecting man against his own ingenuity, the reproductive processes were affected for a time; men became sterile, women had miscarriages, menstruation stopped.

(10) Freda Kirchwey , The Nation (18th August, 1945)

The bomb that hurried Russia into Far Eastern war a week ahead of schedule and drove Japan to surrender has accomplished the specific job for which it was created. From the point of view of military strategy, $2,000,000,000 (the cost of the bomb and the cost of nine days of war) was never better spent. The suffering, the wholesale slaughter it entailed, have been outweighed by its spectacular success; Allied leaders can rightly claim that the loss of life on both sides would have been many times greater if the atomic bomb had not been used and Japan had gone on fighting. There is no answer to this argument. The danger is that it will encourage those in power to assume that, once accepted as valid, the argument can be applied equally well in the future. If that assumption should be permitted, the chance of saving civilization - perhaps the world itself - from destruction is a remote one.

(11) Henry Wallace, letter to Harry S. Truman (24th September, 1945).

You have asked for the comment, in writing, of each cabinet officer on the proposal submitted by Secretary Stimson for the free and continuous exchange of scientific information (not industrial blueprints and engineering "know-how") concerning atomic energy between all of the United Nations. I agreed with Henry Stimson.

At the present time, with the publication of the Smyth report and other published information, there are no substantial scientific secrets that would serve as obstacles to the production of atomic bombs by other nations. Of this I am assured by the most competent scientists who know the facts. We have not only already made public much of the scientific information about the atomic bomb, but above all with the authorization of the War Department we have indicated the road others must travel in order to reach the results we have obtained.

With respect to future scientific developments I am confident that both the United States and the world will gain by the free interchange of scientific information. In fact, there is danger that in attempting to maintain secrecy about these scientific developments we will, in the long run, as a prominent scientist recently put it, be indulging "in the erroneous hope of being safe behind a scientific Maginot Line."

The nature of science and the present state of knowledge in other countries are such that there is no possible way of preventing other nations from repeating what we have done or surpassing it within five or six years. If the United States, England, and Canada act the part of the dog in the manger on this matter, the other nations will come to hate and fear all Anglo-Saxons without our having gained anything thereby. The world will be divided into two camps with the non- Anglo-Saxon world eventually superior in population, resources, and scientific knowledge.

We have no reason to fear loss of our present leadership through the free interchange of scientific information. On the other hand, we have every reason to avoid a shortsighted and unsound attitude which will invoke the hostility of the rest of the world.

In my opinion, the quicker we share our scientific knowledge the greater will be the chance that we can achieve genuine and durable world cooperation. Such action would be interpreted as a generous gesture on our part and lay the foundation for sound international agreements that would assure the control and development of atomic energy for peaceful use rather than destruction.