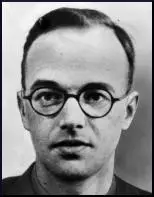

Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Fuchs was born on 29th December, 1911, in Rüsselsheim, Germany. He was the third child in the family of two sons and two daughters of Emil Fuchs and his wife, Else Wagner. According to Mary Flowers: "His father, renowned for his high Christian principles, was a pastor in the Lutheran church who joined the Quakers later in life and eventually became professor of theology at Leipzig University. Fuchs's grandmother, mother, and one sister all took their own lives, while his other sister was diagnosed as schizophrenic." (1)

Klaus Fuchs studied physics and mathematics at the University of Leipzig and in 1931 he joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He fled the country when Adolf Hitler took power in 1933. He taught in Paris before moving to England. (2) He settled in Bristol and studied under Nevill Francis Mott, the Melville Wills Professor in Theoretical Physics at the University of Bristol. Soon after he arrived in the city he was the subject of a police enquiry. "The German Counsul in Bristol named him as an extremist left-wing agitator. Not a great deal of credence was given to the allegation because such denunciations were fairly frequent and anyway the young physicist was just one of thousands of Germans who fled their homeland for ideological reasons." (3)

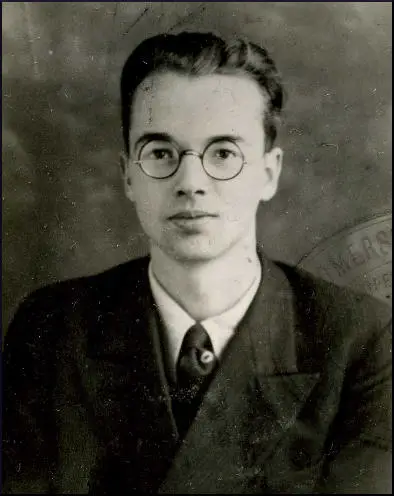

Klaus Fuchs & Max Born

After obtaining his PhD. He took a DSc at Edinburgh University under the guidance of Max Born, one of the pioneers of the new quantum mechanics. After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 he was interned with other German refugees in camps on the Isle of Man. According to Andrew Boyle, The Climate of Treason (1979): "His spell behind barbed wire had merely hardened Fuchs's secret Communist faith, a process not reversed by the German attack on the Soviet Union." (4). He was then transferred to Sherbrooke Camp in Canada where he met Hans Kahle, who had fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Kahle gave Fuchs some addresses of left wing friends, including that of Charlotte Haldane. (5)

Klaus Fuchs was was released following representations from many distinguished scientists, protesting that his skills were going to waste. Rudolf Peierls, who worked at Birmingham University, recruited Klaus Fuchs to help him with his research into atomic weapons: "In 1940, when it was clear that an atomic weapon was a serious possibility, and that it was urgent to do experimental and theoretical work, I wanted someone to help me with the theoretical side. Most competent theoreticians were already doing something important, and when I heard that Fuchs, whom I knew and respected as a physicist from his work at Bristol, was back in the UK, temporarily in Edinburgh, it seemed a good idea to try to get him to come to Birmingham. There was at first some difficulty about security clearance, and I was told I could not tell him what it was all about... I explained that in the kind of work that had to be done he could be of no use to me and unless he knew exactly what one was trying to do, and that there was no half-way house. In the end he was cleared." (6)

According to a document in the NKVD archives, Klaus Fuchs began spying for the Soviet Union in August 1941: "Klaus Fuchs has been our source since August 1941, when he was recruited through the recommendation of Urgen Kuchinsky (an exiled German Communist resident in Great Britain). In connection with the laboratory's transfer to America, Fuchs's departure is expected, too. I should inform you that measures to organize a liaison with Fuchs in America have been taken by us, and more detailed data will be conveyed in the course of passing Fuchs to you." (7) Another file says that Fuchs passed material to their agent for the first time in September 1941.

Fuch's Soviet controller was Ursula Beurton: "Klaus and I never spent more than half an hour together when we met. Two minutes would have been enough but, apart from the pleasure of the meeting, it would arouse less suspicion if we took a little walk together rather than parting immediately. Nobody who did not live in such isolation can guess how precious these meetings with another German comrade were." (8)

Manhattan Project

In 1943 Klaus Fuchs went with Peierls to join the Manhattan Project, which was the codename given to the American atomic bomb programme based in Los Alamos. However, Fuchs was based in the research unit in New York City. Over the next few months he met five times with his Soviet contact. On 21st January, 1944, the agent sent a report on Fuchs to GRU headquarters: "While working with us, Fuchs passed us a number of theoretical calculations on atomic fission and creation of the uranium bomb... His materials were appraised highly." The report also stated that Fuchs was a "devout Communist... whose only financial reward consisted of occasional gifts." (9)

Fuchs's courier was Harry Gold. He sometimes went to the house of Fuchs' sister, who was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to meet with Fuchs. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999), has pointed out: "The NKVD had chosen Gold, an experienced group handler, as Fuchs' contact on the grounds that it was safer than having him meet directly with a Russian operative, but Semyon Semyonov was ultimately responsible for the Fuchs relationship." (10)

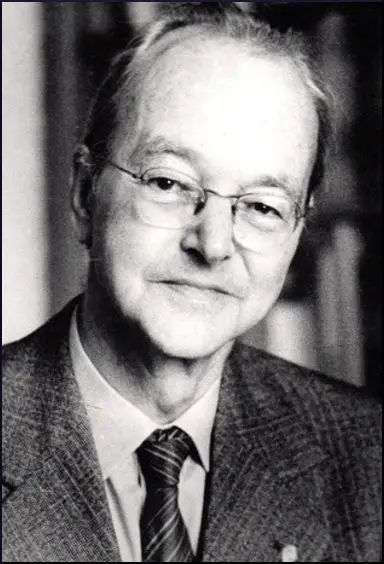

Klaus Fuchs - Soviet Spy

Gold reported after his first meeting with Klaus Fuchs: "He (Fuchs) obviously worked with our people before and he is fully aware of what he is doing... He is a mathematical physicist... most likely a very brilliant man to have such a position at his age (he looks about 30). We took a long walk after dinner... He is a member of a British mission to the U.S. working under the direct control of the U.S. Army... The work involves mainly separating the isotopes... and is being done thusly: The electronic method has been developed at Berkeley, California, and is being carried out at a place known only as Camp Y... Simultaneously, the diffusion method is being tried here in the East... Should the diffusion method prove successful, it will be used as a preliminary step in the separation, with the final work being done by the electronic method. They hope to have the electronic method ready early in 1945 and the diffusion method in July 1945, but (Fuchs) says the latter estimate is optimistic. (Fuchs) says there is much being withheld from the British. Even Niels Bohr, who is now in the country incognito as Nicholas Baker, has not been told everything." (11)

Fuchs met Gold for a second meeting on 25th February, 1944, where he turned material with his personal work on "Enormoz". At a third meeting on 11th March, he delivered fifty additional pages. Gold reported to Semyon Semyonov that "(Klaus Fuchs) asked me how his first stuff had been received, and I said quite satisfactorily but with one drawback: references to the first material, bearing on a general description of the process, were missing, and we especially needed a detailed schema of the entire plant. Clearly, he did not like this much. His main objection, evidently, was that he had already carried out this job on the other side (in England), and those who receive these materials must know how to connect them to the scheme. Besides, he thinks it would be dangerous for him if such explanations were found, since his work here is not linked to this sort of material. Nevertheless, he agreed to give us what we need as soon as possible." (12) On 28th March, 1944, Fuchs complained to Gold that "his work here is deliberately being curbed by the Americans who continue to neglect cooperation and do not provide information." He even suggested that he might learn more by returning to England. If Fuchs went back, "he would be able to give us more complete general information but without details." (13)

Frustrated at the lack of success in the United States in October 1944 Major Pavel Fitin sent Leonid Kvasnikov to build up a network of atomic spies. The following month Kvasnikov was pleased to hear that Fuchs had been transferred to Los Alamos. This included Fuchs, Theodore Hall, Harry Gold, Julius Rosenberg, David Greenglass and Ruth Greenglass. On 8th January, 1945, Kvasnikov sent a message to Fitin about the progress he was making. "(David Greenglass) has arrived in New York City on leave... In addition to the information passed to us through (Ruth Greenglass), he has given us a hand-written plan of the layout of Camp-2 and facts known to him about the work and the personnel. The basic task of the camp is to make the mechanism which is to serve as the detonator. Experimental work is being carried out on the construction of a tube of this kind and experiments are being tried with explosive." (14)

Major Pavel Fitin, the head of NKVD's foreign intelligence unit, claimed that Klaus Fuchs was the most important figure in the project he had given the codename "Enormoz". In November 1944 he reported: "Despite participation by a large number of scientific organization and workers on the problem of Enormoz in the U.S., mainly known to us by agent data, their cultivation develops poorly. Therefore, the major part of data on the U.S. comes from the station in England. On the basis of information from London station, Moscow Center more than once sent to the New York station a work orientation and sent a ready agent, too (Klaus Fuchs)." (15) Another memorandum from NKVD stated that "Fuchs is an important figure with significant prospects and experience in agent's work acquired over two years spent working with the neighbors (GRU). After determining at early meetings his status in the country and possibilities, you may move immediately to the practical work of acquiring information and materials." (16)

The Soviet government was devastated when the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th and 9th August, 1945. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "On August 25, Kvasnikov responded that the station had not yet received agent reports on the explosions in Japan. As for Fuchs and Greenglass, their next meetings with Gold were scheduled for mid-September. Moscow found Kvasnikov's excuses unacceptable and reminded him on August 28 of the even greater future importance of information on atomic research, now that the Americans had produced the most destructive weapon known to humankind." (17)

Pavel Fitin wrote to Vsevolod Merkulov: "Practical use of the atomic bomb by the Americans means the completion of the first stage of enormous scientific-research work on the problem of releasing intra-atomic energy. The fact opens a new epoch in science and technology and will undoubtedly result in rapid development of the entire problem of Enormoz - using intra-atomic energy not only for military purposes but in the entire modern economy. All this gives the problem of Enormoz a leading place in our intelligence work and demands immediate measures to strengthen our technical intelligence." (18)

Harwell Research Centre

In 1946 Klaus Fuchs returned to England, where he was appointed by John Cockcroft as head of the theoretical physics division at the newly created British Nuclear Research Centre at Harwell. Fuchs approached members of the Communist Party of Great Britain in order to get back in contact with the NKVD. On 19th July, 1947, Fuchs met Hanna Klopshtock in Richmond Park.

Klopshtock arranged for Fuchs to meet Alexander Feklissov, London's deputy station chief for scientific and technical intelligence. Fuchs explained to Feklissov the principle of the hydrogen bomb on which Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller were working on at the University of Chicago. (19) Feklissov reported: "I thanked him once again for helping us and, having noted that we know about his refusal to accept material help from us in the past, said that now conditions had changed: his father was his dependent, his ill brother (who has tuberculosis) needed his help... therefore we considered it imperative to propose our help as an expression of gratitude." (20) Fuchs was given £200. However, he returned £100 on the grounds that he could not explain the sudden appearance of £200.

In March 1948, Feklissov received orders to keep clear of Klaus Fuchs. This was because the Daily Express had reported that British counter-intelligence were investigating three unnamed scientists who were suspected of being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. (21) Feklissov was also told that one of Fuchs' former contacts (Ursula Beurton) had been interviewed by the FBI. The point was made that Fuchs would probably not now be in a position to give them any worthwhile information as even if he was not arrested, he would probably be barred from participating in secret scientific research work on the atomic problem. However, Feklissov continued to have meetings with Fuchs.

Klaus Fuchs & Verona Project

The NKVD became especially concerned when Judith Coplon was arrested on 4th March, 1949 in New York City as she met with Valentin Gubitchev, a Soviet employee on the United Nations staff. They discovered that she had in her handbag twenty-eight FBI memoranda. Eight days later Moscow sent Feklissov a message: "In connection with the latest events in (New York City) and in order to avoid repetition of such cases in other places, it is necessary to revise urgently and most carefully the practice of holding meetings... We ask you to revise... all methods for carrying out meetings, especially with (Fuchs)." (22)

On 12th September 1949, MI5 was sent documents that had been uncovered by the Venona Project that suggested that Fuchs was a Soviet spy. His telephones were tapped and his correspondence intercepted at both his home and office. Concealed microphones were installed in Fuchs's home in Harwell. Fuchs was tailed by B4 surveillance teams, who reported that he was difficult to follow. Although they discovered he was having an affair with the wife of his line manager, the investigation failed to produce any evidence of espionage.

In January 1950, Percy Sillitoe, the head of MI5, wrote to Fuchs's boss, Sir Archibald Rowlands pointing out: "We have had Fuchs' activities under intensive investigation for more than four months. Since it has been generally agreed that Fuchs' continued employment is a constant threat to security and since our elaborate investigation has produced no dividends, I should be grateful if you would be kind enough to arrange for Fuchs' departure from Harwell as soon as is decently possible." (23)

Confession

Fuchs was interviewed by MI5 officers but he denied any involvement in espionage and the intelligence services did not have enough evidence to have him arrested and charged with spying. Jim Skardon later recalled: "He (Klaus Fuchs) was obviously under considerable mental stress. I suggested that he should unburden his mind and clear his conscience by telling me the full story." Fuchs replied "I will never be persuaded by you to talk." The two men then went to lunch: "During the meal he seemed to be resolving the matter and to be considerably abstracted... He suggested that we should hurry back to his house. On arrival he said that he had decided it would be in his best interests to answer my questions. I then put certain questions to him and in reply he told me that he was engaged in espionage from mid 1942 until about a year ago. He said there was a continuous passing of information relating to atomic energy at irregular but frequent meetings." (24)

Fuchs explained to Skardon: "Since that time I have had continuous contact with the persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would hand whatever information I gave them to the Russian authorities. At that time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore, no hesitation in giving all the information I had, even though occasionally I tried to concentrate mainly on giving information about the results of my own work. There is nobody I know by name who is concerned with collecting information for the Russian authorities. There are people whom I know by sight whom I trusted with my life." (25) A few days later J. Edgar Hoover informed President Harry S. Truman that "we have just gotten word from England that we have gotten a full confession from one of the top scientists, who worked over here, that he gave the complete know-how of the atom bomb to the Russians." (26) As Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) pointed out: "What Fuchs had failed to realize was that, but for his confession, there would have been no case against him, Skardon's knowledge of his espionage, which had so impressed him, derived from... Verona... and unusable in court." (27)

Klaus Fuchs was found guilty on 1st March 1950 of four counts of breaking the Official Secrets Act by "communicating information to a potential enemy". After a trial lasting less than 90 minutes, Lord Rayner Goddard sentenced him to fourteen years' imprisonment, the maximum for espionage, because the Soviet Union was classed as an ally at the time. (28) Hoover reported that "Fuchs said he would estimate that the information furnished by him speeded up by several years the production of an atom bomb by Russia." (29)

Fuchs was released on 23rd June 1959 after serving nine years and four months. Immediately after leaving Wakefield Prison he joined his father and one of his nephews in what had become the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where he was appointed deputy director of the Institute for Nuclear Research near Dresden. Fuchs married a friend from his student days, a fellow communist called Margarete Keilson. They had no children. (30)

Klaus Fuchs died on 28th January, 1988.

Primary Sources

(1) Rudolf Peierls, interviewed by Andrew Boyle for his book The Climate of Treason (1979)

In 1940, when it was clear that an atomic weapon was a serious possibility, and that it was urgent to do experimental and theoretical work, I wanted someone to help me with the theoretical side. Most competent theoreticians were already doing something important, and when I heard that Fuchs, whom I knew and respected as a physicist from his work at Bristol, was back in the UK, temporarily in Edinburgh, it seemed a good idea to try to get him to come to Birmingham. There was at first some difficulty about security clearance, and I was told I could not tell him what it was all about.... I explained that in the kind of work that had to be done he could be of no use to me unless he knew exactly what one was trying to do, and that there was no half-way house. In the end he was cleared.

(2) Percy Sillitoe, letter to Sir Archibald Rowlands (19th January, 1950)

We have had Fuchs' activities under intensive investigation for more than four months. Since it has been generally agreed that Fuchs' continued employment is a constant threat to security and since our elaborate investigation has produced no dividends, I should be grateful if you would be kind enough to arrange for Fuchs' departure from Harwell as soon as is decently possible.

(3) William Skardon, report on Klaus Fuchs (31st January, 1950)

He was obviously under considerable mental stress. I suggested that he should unburden his mind and clear his conscience by telling me the full story. He (Fuchs) said: "I will never be persuaded by you to talk." At this stage we went to lunch. During the meal he seemed to be resolving the matter and to be considerably abstracted... He suggested that we should hurry back to his house. On arrival he said that he had decided it would be in his best interests to answer my questions. I then put certain questions to him and in reply he told me that he was engaged in espionage from mid 1942 until about a year ago. He said there was a continuous passing of information relating to atomic energy at irregular but frequent meetings.

(4) Klaus Fuchs, confession to William Skardon (27th January, 1950)

I was a student in Germany when Hitler came to power. I joined the Communist Party because I felt I had to be in some organization. I was in the underground until I left Germany. The Communist Party said that I must finish my studies because after the revolution in Germany people would be required with technical knowledge to take part in the building of the Communist Germany. I went first to France and then to England, where I studied and at the same time I tried to make a serious study of the bases of Marxist philosophy.

I had my doubts for the first time (August, 1939) on acts of foreign policies of Russia; the Russo-German pact was difficult to understand, but in the end I did accept that Russia had done it to gain time, that during the time she was expanding her own influence in the Balkans against the influence of Germany.

Shortly after my release (from detention as an enemy alien) I was asked to help Professor Peierls in Birmingham, on some war work. When I learned the purpose of the work I decided to inform Russia and I established contact through another member of the Communist Party. Since that time I have had continuous contact with the persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would hand whatever information I gave them to the Russian authorities. At that time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore, no hesitation in giving all the information I had, even though occasionally I tried to concentrate mainly on giving information about the results of my own work.

There is nobody I know by name who is concerned with collecting information for the Russian authorities. There are people whom I know by sight whom I trusted with my life.

(5) Klaus Fuchs, confession released to the public after his trial in 1950.

When I learnt of the purpose of the work, I decided to inform Russia, and I established contact with another member of the Communist Party. Since that time I have had continuous contact with persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would give whatever information they had to the Soviet authorities. At this time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Germany and Russia to fight each other to death.