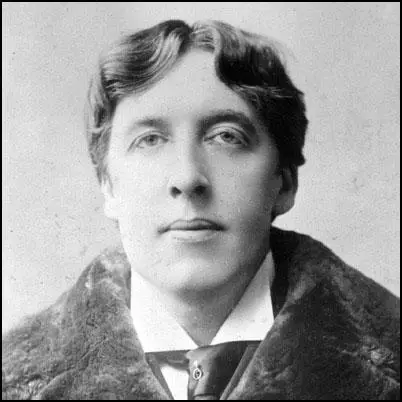

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde, the second of the three children of William Robert Wills Wilde (1815–1876) and his wife, Jane Francesca Elgee (1821–1896) was born in Dublin on 16th October 1854. His father was a surgeon and his mother held a literary salon at their home. Visitors included Aubrey de Vere, Samuel Ferguson, William Carleton and John Thomas Gilbert.

Wilde won a scholarship to Trinity College in 1871. his chief mentors were the classicists John Pentland Mahaffy and Robert Yelverton Tyrrell. He won a foundation scholarship in 1873 and the Berkeley gold medal for Greek in 1874. He also met Edward Carson while at university.

In June 1874, Wilde won a demyship in classics to Magdalen College. He graduated in November 1878 with a double first in classical moderations and Greats (classics). His biographer, Owen Dudley Edwards, has argued: "Dublin probably educated him better than Oxford, but Oxford gave him a new world of expression and audience. In place of the Dublin wits and scholars vying to outsmart one another, he found intellectuals whose oratorical articulacy was declining as his own developed".

A brilliant student, his poem Ravenna won the 1878 Newdigate Prize. After the death of his father, Wilde and his mother settled in London in 1879. They were both supporters of Charles Stewart Parnell and Home Rule. A regular visitor to the theatre, Wilde became friends with the actresses, Lily Langtry, Ellen Terry and Sarah Bernhardt.

In 1882 Wilde went on a lecture tour of the United States and Canada. When immigration officials in New York City asked him if he had anything to declare he replied, "Only my genius". He received $6,000 for delivering nearly 150 lectures over the next 12 months. Titles of his lectures included The Decorative Arts, The House Beautiful, The English Renaissance and Irish Poets and Poetry in the Nineteenth Century.

Frank Harris met him during this period: "Oscar Wilde's humor was an extraordinary gift and sprang to show on every occasion. Whenever I meet anyone who knew Oscar Wilde at any period of his life, I am sure to hear a new story on him - some humorous or witty thing he has said... I have often been asked since to compare Oscar's humor with Shaw's. I have never thought Shaw humorous in conversation. It was on the spur of the moment that Oscar's humor was so extraordinary, and it was this spontaneity that made him so wonderful a companion. Shaw's humor comes from thought and the intellectual angle from which he sees things, a dry light thrown on our human frailties."

Wilde moved to Paris in January 1883 and over the next few months met Victor Hugo, Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé, Edmond de Goncourt, Edgar Degas, Alphonse Daudet and Emile Zola. He also became friendly with Robert Harborough Sherard (1861–1943), whom he saw almost every day. Wilde also became a regular book critic for the Pall Mall Gazette.

On 25th November 1883 he became engaged to Constance Mary Lloyd (1858–1898). They married at St James's Church, Sussex Gardens, Paddington, on 29th May 1884. Constance gave birth to two sons, Cyril (June, 1885) and Vyvyan (November, 1886).

In 1886 Wilde met Robert Ross. According to Frank Harris the two men had become acquainted in a public lavatory. However, Maureen Borland, the author of Wilde's Devoted Friend: Life of Robert Ross (1990) claims that this is a "scurrilous and uncorroborated suggestion" and that "it is much more likely that Alex Ross, Robert's elder brother and a literary critic, made the introduction, possibly at the Savile Club."

It is believed that this was Wilde's first homosexual relationship. Wilde's biographer, Owen Dudley Edwards, has argued that the relationship started after his wife lost interest in sex after the birth of their second son: "Remembering his father's sexual infidelities (resulting in at least three bastards), Wilde recoiled from the thought of sexual solace with other women, and Ross seems to have exploited his sexual hunger and refusal to betray his heterosexual bed. Wilde never seems to have engaged in anal penetration either actively or passively."

When the boys were children Oscar Wilde wrote fairy stories for them that were later published as The Happy Prince and Other Tales (1888). One critic wrote: "In all cases they are on the child's side, celebrating the courage and generosity of the poor and vulnerable, while their satire mocks the kind of pomposity and hypocrisy children can recognize." The book was illustrated by his good friend, Walter Crane.

In 1889 Oscar Wilde met twenty-three year old poet, John Gray. He immediately fell in love with Gray. Wilde later described him as being: "Wonderfully handsome, with his finely-curved scarlet lips, his frank blue eyes, his crisp gold hair. There was something in his face that made one trust him at once. All the candour of youth was there, as well as all youth's passionate purity. One felt that he had kept himself unspotted from the world." A mutual friend, Lionel Johnson, said that he had the "face of a fifteen" year-old boy. George Bernard Shaw recalled that he was "one of the more abject of Wilde's disciples".

Wilde decided to write a story that would revive a debate that he had with James McNeill Whistler, four years earlier. Wilde had argued that poetry and prose were superior to painting and sculpture because the writer could make use of all experience rather than a part: "The statue is concerned in one moment of perfection. The image stained upon the canvas possesses no spiritual element of growth or change. If they know nothing of death, it is because they know little of life, for the secrets of life belong to those, and those only, whom the sequence of time affects, and who possess not merely the present but the future, and can rise or fall from a past of glory or of shame. Movement, that problem of the visible arts, can be truly realised by Literature alone."

Wilde also wanted to challenge the new naturalism movement that was headed by the novelist Émile Zola. Wilde argued: "Zola's characters have their dreary vices, and their still drearier virtues. The record of their lives is absolutely without interest. Who cares what happens to them? In literature we require distinction, charm, beauty and imaginative power. We don't want to be harrowed and disgusted with an account of the doings of the lower orders." He suggested that "the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of art".

The Picture of Dorian Gray appeared in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine on 20th June 1890. The story tells of a young man named Dorian Gray (John Gray), who is being painted by Basil Hallward. The artist is fascinated by Dorian's beauty and becomes infatuated with him. Lord Henry Wotton meets Dorian at Hallward's studio. Espousing a new hedonism, Wotton suggests the only things worth pursuing in life are beauty and fulfillment of the senses.

When Dorian Gray sees the portrait he remarks: "How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young. It will never be older than this particular day in June... If it were only the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that - for that - I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!" In the story Dorian's wish is fulfilled.

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Richard Ellmann has argued: "To give the hero of his novel the name of Gray was a form of courtship. Wilde probably named his hero not to point to a model, but to flatter Gray by identifying him with Dorian. Gray took the hint, and in letters to Wilde signed himself Dorian. Their intimacy was common talk... Wilde and Gray were assumed to be lovers, and there seems no reason to doubt it." As a result some critics believed the book, named after his lover, promoted homosexuality. On 30th June, 1890 The Daily Chronicle suggested that Wilde's story contains "one element... which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it."

The most hostile review came from Charles Whibley in The Scots Observer . "Why go grubbing in muck heaps? The world is fair, and the proportion of healthy-minded men and honest women to those that are foul, fallen and unnatural, is great. Mr Oscar Wilde has again been writing stuff that were better unwritten; and while The Picture of Dorian Gray, which he contributes to Lippincott's is ingenious, interesting, full of cleverness, and plainly the work of a man of letters, it is false art - for its interest is medico-legal; it is false to human nature - for its hero is a devil; it is false to morality - for it is not made sufficiently clear that the writer does not prefer a course of unnatural iniquity to a life of cleanliness, health and sanity. The story which deals with matters fitted only for the Criminal Investigation Department or a hearing in camera is discreditable alike to author and editor. Mr Wilde has brains, and art, and style; but if he can write for none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys, the sooner he takes to tailoring (or some other decent trade) the better for his own reputation and the public morals."

Whibley's comments about "outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys" was a reference to the so-called Cleveland Street scandal. This was particularly offensive to Wilde. The scandal involved Arthur Somerset, the son of the 8th Duke of Beaufort and the Henry James FitzRoy, the son of the 7th Duke of Grafton, who were said to have frequented a homosexual brothel off the Tottenham Court Road. According to Harford Montgomery Hyde, the author of Oscar Wilde (1975), this was "where telegraph-boys from the General Post Office were able to earn additional money by going to bed with the Cleveland Street establishment's aristocratic customers." Wilde saw this as an attempt to link him with a homosexual scandal.

Wilde wrote to William Ernest Henley, the editor of the newspaper: "Your reviewer suggests that I do not make it sufficiently clear whether I prefer virtue to wickedness or wickedness to virtue. An artist, sir, has no ethical sympathies at all. Virtue and wickedness are to him simply what the colours on his palette are to the painter. They are no more, and they are no less. He sees that by their means a certain artistic effect can be produced and he produces it. Iago may be morally horrible and Imogen stainlessly pure. Shakespeare, as Keats said, had as much delight in creating the one as he had in creating the other."

Wilde was concerned by the suggestions that he was trying to promote an illegal act. He decided to turn the short-story into a novel by adding six chapters. He also took the opportunity to remove some of the passages that indicated that The Picture of Dorian Gray was about homosexual love. Wilde also added a Preface that was a series of aphorisms that attempted to answer some of the criticisms of the original story. This included: "There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written."

Wilde also used the Preface to attack the naturalism movement: "No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style... No artist is ever morbid... Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril... The artist is the creator of beautiful things. To reveal art and conceal the artist is art's aim."

The amended version of The Picture of Dorian Gray was published by Ward, Lock and Company in April 1891. Again the reception was extremely hostile. Samuel Henry Jeyes demanded in the St James's Gazette that the book be burnt and hinted that its author was more familiar with homosexuality than he should have been. The country's leading bookshop, W. H. Smith refused to stock what it described as a "filthy book".

The only good review was by his friend, Walter Pater, in The Bookman. "There is always something of an excellent talker about the writing of Mr Oscar Wilde; and in his hands, as happens so rarely with those who practise it, the form of dialogue is justified by its being really alive. His genial, laughter-loving sense of life and its enjoyable intercourse, goes far to obviate any crudity there may be in the paradox, with which, as with the bright and shining truth which often underlies it... Dorian himself, though certainly a quite unsuccessful experiment in Epicureanism, in life as a fine art, is (till his inward spoiling takes visible effect suddenly, and in a moment, at the end of his story) a beautiful creation. But his story is also a vivid, though carefully considered, exposure of the corruption of a soul, with a very plain moral pushed home, to the effect that vice and crime make people coarse and ugly."

Arthur Machen met Oscar Wilde for the first time in the summer of 1890. Machen later recalled: "He (Wilde) was a man of distinguished appearance. He was not handsome - there was something mis-shapen about his mouth - but he was impressive in a high degree... He would say ridiculous things, but he expected you to laugh at them, not to take them as prophetic utterances... I may say that so far as I knew him there was nothing of depth in his talk. He glided fantastically, whimsically, over the surface of things."

Later that year Machen had another meeting with Wilde: "He dined with me once again.... And on this occasion, I do remember being struck with the fact that there was a certain sameness in Wilde's talk. It was not that he repeated himself or said over again the things that he had said before: rather, the mould of his conversation remained the same, the manner was the same, the turns and tricks and quips were all in the one vein. No new mood was indicated, no different angle of vision was manifested. But this, very unlikely and for all I know, may have been due to the fact that Wilde saw that there was no real sympathy between us, no vital common ground, as it were; and so he set himself to be politely - and delightfully - entertaining in his usual manner."

Wilde's next book, The Soul of Man under Socialism (1891), considered the role of the artist. In the book Wilde made the controversial statement: "Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man's original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion." Owen Dudley Edwards has described the book as "perhaps the most memorable and certainly the most aesthetic statement of anarchist theory in the English language."

In June 1891, Robert Ross introduced Wilde to Alfred Douglas. The two men entered into a sexual relationship. They also worked together and in 1892 Douglas was involved in the French production of Wilde's play, Salomé. They attempted to get it produced in London with Sarah Bernhardt taking the star role but it was banned by the Lord Chamberlain as being blasphemous. Wilde later recalled: "I was a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age.... But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flaneur, a dandy, a man of fashion. I surrounded myself with the smaller natures and the meaner minds. I became the spendthrift of my own genius, and to waste an eternal youth gave me a curious joy. Tired of being on the heights, I deliberately went to the depths in the search for new sensation. What the paradox was to me in the sphere of thought, perversity became to me in the sphere of passion. Desire, at the end, was a malady, or a madness, or both. I grew careless of the lives of others. I took pleasure where it pleased me, and passed on. I forgot that every little action of the common day makes or unmakes character, and that therefore what one has done in the secret chamber one has some day to cry aloud on the housetop. I ceased to be lord over myself. I was no longer the captain of my soul, and did not know it."

It was decided that Salomé should be published in book form and the Pall Mall Budget asked Beardsley for a drawing to illustrate the review. The editor rejected the drawing as being obscene. However, in April, 1893, it appeared in the first number of The Studio magazine. Wilde liked the drawing, and his publisher, John Lane, the founder of The Bodley Head, suggested that Beardsley do an illustrated edition of the play. Wilde and Lane were both very pleased with the illustrations Beardsley produced. One of the drawings was considered by Lane as indecent and was not used in the book. Beardsley reacted by writing a short poem:

Because one figure was undressed.

This little drawing was suppressed.

It was unkind. But never mind,

Perhaps it was all for the best.

In October 1893 a dispute broke out between Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Alfred Douglas and John Lane over the French translation of Salomé. Wilde's biographer, Richard Ellmann, has argued: "Beardsley read the translation and said it would not do; he offered to make one of his own. Wilde, fortunately for Douglas, did not like this either. There ensued an acrimonious fourway controversy among Lane, Wilde, Douglas, and Beardsley. Lane said that Douglas had shown disrespect for Wilde, but backed down when Douglas accused him of stirring up trouble between them. Beardsley declared that it would be dishonest to put Douglas's name on the title page, when the translation had been so much altered by Wilde."

Beardsley wrote to his friend, the art critic, Robert Ross: "I suppose you've heard all about the Salomé row. I can tell you I had a warm time of it between Lane and Oscar and company. For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous. I really don't quite know how matters really stand now... The book will be out soon after Xmas. I have withdrawn three of the illustrations and supplied their places with three new ones (simply beautiful and quite irrelevant."

That summer Wilde decided to write a comedy. Lady Windermere's Fan was finished in October and it was offered to George Alexander, the actor manager of St James's Theatre. Alexander liked the play, and offered him £1,000 for it. Wilde, confident of its future success, opted to take a percentage instead. The play opened on 20th February 1892. It was a great success and Wilde responded by making a short speech on the stage: "Ladies and Gentlemen. I have enjoyed this evening immensely. The actors have given us a charming rendition of a delightful play, and your appreciation has been most intelligent. I congratulate you on the great success of your performance, which persuades me that you think almost as highly of the play as I do myself." Wilde received £7,000 in royalities in its first year of production.

Herbert Beerbohm Tree, the actor-manager of the Haymarket Theatre, asked Oscar Wilde to write him a play. Wilde was not convinced that he was the right man to act in one of his dark comedies. He told him: "You must forget that you ever played Hamlet; you must forget that you ever played Falstaff; above all, you must forget that you ever played a duke in a melodrama by Henry Arthur Jones."

Wilde wrote A Woman of No Importance while staying with Alfred Douglas at a farmhouse near Felbrigg. The play opened on 19th April 1893. Except for William Archer, the critics did not like the play and it closed in August. Richard Ellmann, the author of Oscar Wilde (1988), has described it as the "weakest of the plays Wilde wrote in the Nineties".

Max Beerbohm was an old friend of Wilde and Douglas. He argued that Douglas could be "very charming" and "nearly brilliant" but was "obviously mad (like all his family)". Douglas also had a sexual relationship with Robert Ross, one of Wilde's former lovers. While he was staying with Ross they had sex with two young boys, aged 14 and 15. Both boys confessed to their parents about what happened. After meetings with solicitors, the parents were persuaded not to go to the police, since, at that time, their sons might be seen not as victims but as equally guilty and so face the possibility of going to prison.

In June 1894 Alfred Douglas received a letter from his father, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, on the subject of his friend, Oscar Wilde: "I now hear on good authority, but this may be false, that his wife is petitioning to divorce him for sodomy and other crimes. Is this true, or do you know of it? If I thought the actual thing was true, and it became public property I should be quite justified in shooting him in sight." Douglas replied with a brief telegram: "What a funny little man you are." This enraged Queensberry who decided to carry out more research into the behaviour of Wilde.

Queensberry arrived at the home of Oscar Wilde at the end of June. Wilde said to Queensberry: "I suppose you have come to apologize for the statement you made about my wife and myself in letters you wrote to your son. I should have the right any day I chose to prosecute you for writing such a letter.... How dare you say such things to me about your son and me?" He replied, "You were both kicked out of the Savoy Hotel at a moment's notice for your disgusting conduct.... You have taken furnished rooms for him in Piccadilly." Wilde told Queensberry: "Somebody has been telling you an absurd set of lies about your son and me. I have not done anything of the kind." Wilde then evicted Queensberry from his home.

That summer Wilde went to stay at a house in Esplanade Court in Worthing. During August he wrote The Importance of being Earnest. He also began a relationship with a 14 year-old newspaper boy Alphonso Conway and his friend Stephen. He took them to Littlehampton for the day. He wrote to Douglas: "Yesterday (Sunday) Alphonso, Stephen and I sailed to Littlehampton in the morning, bathing on the way. We took five hours in an awful gale to come back and did not reach the pier till eleven o'clock at night, pitch dark all the way, and a fearful sea. I was drenched, but Viking-like and daring. It was, however, quite a dangerous adventure. All the fishermen were waiting for us. I flew to the hotel for hot brandy and water on landing with my companions... As it was past ten o'clock on a Sunday night the proprietor could not sell us any brandy or spirits of any kind! So he had to give it to us. The result was not displeasing, but what laws! A hotel proprietor is not allowed to sell necessary harmless' alcohol to three shipwrecked mariners, wet to the skin, because it is Sunday! Both Alphonso and Stephen are now anarchists, I need hardly say."

Wilde was invited to give a speech at the Worthing Regatta. The Worthing Gazette reported that Wilde praised the high quality entertainment available but disliked the growing commercialism in the town. He also liked the "splendor of the scenery" and added: "It (Worthing) has beautiful surroundings and lovely long walks, which I recommend to other people, but never take myself... To my mind few things are so important as the capacity to be amused, feeling pleasure, and giving it to others. For whenever a person is happy, he is good, although perhaps when he is good he is not always happy." Chris Hare, the author of Worthing: A History (2008) has commented: "Loud applause and laughter followed those remarks, though Wilde would doubtless have received a different response had the audience known the truth about his private life or the 'pleasures' he was indulging in with two local teenage boys."

The amended version of The Picture of Dorian Gray was published by Ward, Lock and Company in April 1891. Again the reception was extremely hostile. Samuel Henry Jeyes demanded in the St James's Gazette that the book be burnt and hinted that its author was more familiar with homosexuality than he should have been. The country's leading bookshop, W. H. Smith refused to stock what it described as a "filthy book".

Wilde's next play, An Ideal Husband, was based on an anecdote provided by his friend, Frank Harris. The play, that deals with blackmail and political corruption, was given to Lewis Waller at the Haymarket Theatre opened on 3rd January, 1895. George Bernard Shaw, wrote in the Saturday Review, that: "Wilde is our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre".

Considered to be his greatest play, The Importance of being Earnest, opened at St James's Theatre on 14th February, 1895. The main character, John Worthing, was played by George Alexander. It was well-received by the critics. H.G. Wells commented "More humorous dealing with theatrical conventions it would be difficult to imagine." However, the play was criticised by two of his strongest supporters. William Archer asked: "What can a poor critic do with a play which raises no principle, whether of art or morals, creates its own canons and conventions, and is nothing but an absolutely wilful expression of an irrepressibly witty personality?" George Bernard Shaw, who found it "extremely funny" but dismissed it as his "first really heartless play".

The 9th Marquess of Queensberry, the father of Alfred Douglas, discovered details of his son's sexual relationship with Wilde and planned to disrupt the opening night of the play by throwing a bouquet of rotten vegetables at the playwright when he took his bow at the end of the show. Wilde learned of the plan and arranged for policemen to bar his entrance. Two weeks later, Queensberry left his card at Wilde's club, the Albemarle, accusing him of being a "sodomite". Wilde, Douglas and Robert Ross approached solicitor Charles Octavius Humphreys with the intention of suing Queensberry for criminal libel. Humphreys asked Wilde directly whether there was any truth to Queensberry's allegations of homosexual activity between Wilde and Douglas. Wilde claimed he was innocent of the charge and Humphreys applied for a warrant for Queensberry's arrest.

Queensberry entered a plea of justification on 30th March. Owen Dudley Edwards has pointed out: "Having belatedly assembled evidence found for Queensberry by very recent recruits, it declared Wilde to have committed a number of sexual acts with male persons at dates and places named. None was evidence of sodomy, nor was Wilde ever charged with it. Queensberry's trial at the central criminal court, Old Bailey, on 3–5 April before Mr Justice Richard Henn Collins ended in Wilde's attempt to withdraw the prosecution after Queensberry's counsel, Edward Carson QC MP, sustained brilliant repartee from Wilde in the witness-box on questions about immorality in his works and then crushed Wilde with questions on his relations to male youths whose lower-class background was much stressed." Richard Ellmann, the author of Oscar Wilde (1988), has argued that Wilde abandoned the case rather than call Douglas as a witness.

Queensberry was found not guilty and his solicitors sent its evidence to the public prosecutor. Frank Harris became convinced that Wilde would be arrested and sent to prison. According to Enid Bagnold: "He (Harris) stood in the prison corridor while Wilde, in a white sweat of nerves, changed his shoes for the prison boots, he arranged for a yacht to lie off Dartford, and the terrible interview he had when Wilde refused to flee before the trial so tore my heart that I could tell my grandchildren I was there myself."

Wilde was arrested on 5th April and taken to Holloway Prison. The following day, Alfred Taylor, the owner of a male brothel Wilde had used, was also arrested. Taylor refused to give evidence against Wilde and both men were charged with offences under the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885). Arthur Machen saw Wilde at this time and he was shocked by his appearance: "Wilde was a shocking sight. He had become a great mass of rosy fat. His body seemed made of rolls of fat. He was pendulous. He was like nothing but an obese old French-woman, of no extraordinary fame, dressed up in man's clothes. He horrified me."

The trial of Wilde and Taylor began before Justice Arthur Charles on 26th April, 1895. Of the ten alleged sexual partners Queensberry's plea had named, five were omitted from the Wilde indictment. The trial under Charles ended in jury disagreement after four hours. The second trial, under Justice Alfred Wills, began on 22nd May. Douglas was not called to give evidence at either trial, but his letters to Wilde were entered into evidence, as was his poem, Two Loves. Called on to explain its concluding line - "I am the love that dares not speak its name" Wilde answered that it meant the "affection of an elder for a younger man".

Wilde attempted to defend his relationship with what became known as the "Love that dare not speak its name" speech: "It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michaelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the Love that dare not speak its name, and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it."

Max Beerbohm, was in court at the time and wrote to his friend, Reginald Turner: "Oscar has been quite superb. His speech about the Love that dares not tell his name was simply wonderful and carried the whole court right away, quite a tremendous burst of applause. Here was this man, who had been for a month in prison and loaded with insults and crushed and buffeted, perfectly self-possessed, dominating the Old Bailey with his fine presence and musical voice. He has never had so great a triumph, I am sure as when the gallery burst into applause - I am sure it affected the jury."

Wilde and Alfred Taylor were both found guilty and sentenced to two years' penal servitude with hard labour. The two known persons with whom Wilde was found guilty of gross indecency were male prostitutes, Wood and Parker. Wilde was also found guilty on two counts charging gross indecency with a person unknown on two separate occasions in the Savoy Hotel. These may in fact have related to acts committed by Douglas, who had also been Wood's lover.

Richard Haldane, under instructions from Herbert Gladstone, visited Oscar Wilde in Pentonville Prison on 12th June, 1895. Haldane managed to arrange for Wilde to gain access to books. Wilde was transferred to Wandsworth Prison on 4th July. His friend, Robert Sherrard, visited Wilde on behalf of Constance Wilde, and urged him to repudiate his homosexual friends. In November he was moved to Reading Prison.

Wilde's health deteriorated while in prison. He received little sympathy from the prison doctor, Oliver Calley Maurice (1838–1907). Wilde petitions to the home secretary asking for release on medical grounds were ignored on Maurice's advice. Wilde was not the only victim of Maurice's medical knowledge. In a letter to The Daily Chronicle, he argued that the prisoners were in mortal danger from Maurice: "It is a horrible duel between himself and the doctor. The doctor is fighting for a theory. The man is fighting for his life. I am anxious that the man should win."

Alfred Douglas remained loyal to Wilde and wrote letters to the newspapers and unsuccessfully petitioned Queen Victoria for clemency for his lover. He also wrote to Truth Magazine: "I personally know forty or fifty men who practise these acts. Men in the best society, members of the smartest clubs, members of Parliament, Peers, etc., in fact people of my own social standing... At Oxford, where I suppose you would admit one is likely to find the pick of the youth of England, I knew hundreds who had these tastes among the undergraduates, not to mention a slight sprinkling of Dons.... These tastes are perfectly natural congenital tendencies in certain people (a very large minority), and that the law has no right to interfere with these people, provided they do not harm other people; that is to say when there is neither seduction of minors nor brutalisation, and where there is no public outrage on morals."

In March 1897, Wilde wrote to Douglas about the death of his mother: "No one knew how deeply I loved and honoured her. Her death was terrible to me; but I, once a lord of language, have no words in which to express my anguish and my shame. She and my father had bequeathed me a name they had made noble and honoured, not merely in literature, art, archaeology, and science, but in the public history of my own country, in its evolution as a nation. I had disgraced that name eternally. I had made it a low by-word among low people. I had dragged it through the very mire. I had given it to brutes that they might make it brutal, and to fools that they might turn it into a synonym for folly."

G. A. Cevasco has argued: "Douglas's loyalty to the imprisoned Wilde, his financial generosity, and continued concern, must be viewed in the context of a turbulent relationship involving two highly self-centred and opinionated individuals." Upon Wilde's release from prison in 1897, he took up with Douglas once again. The two men lived together for a while in Naples and after they they met frequently in Paris. Douglas also helped Wilde financially.

An edited version of De Profundis was published in 1897. Owen Dudley Edwards has argued: "It did not deny his own culpability for the wreck of his and his family's lives, but it made his obsession with Douglas the leading count in his own self-indictment. It attacked Douglas for hatred of his father, acknowledged his love for Wilde, but saw that love, like Wilde himself, enslaved in the work of hate. Ross was held up as a model of friendship and stimulus. Yet the power and profundity of De Profundis itself asserted Douglas's far more cataclysmic inspirational effect. Nor was the contrast accurate in all respects. Both Ross and Douglas were demanding, self-centred, and indiscreet, and Wilde's relationship to both of them was more that of an indulgent but exploited uncle than of the physical lover he seems to have been for a relatively brief time in each case. Both Ross and Douglas were homosexual liberationists, Ross more constructively, Douglas more flamboyantly."

In 1898 Wilde published The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a poem inspired by his prison experiences. It included an account of the hanging of Charles Thomas Wooldridge (1866–1897), a trooper of the Royal Horse Guards, who had murdered his wife while suffering from mental illness. G. K. Chesterton described the poem as "a cry for common justice and brotherhood very much deeper, more democratic" than other forms of protest.

Augustus John, Charles Conder and William Rothenstein went to Paris to visit Wilde. John later recalled: " I had heard a lot about Oscar, of course, and on meeting him was not in the least disappointed, except in one respect: prison discipline had left one, and apparently only one, mark on him, and that not irremediable: his hair was cut short... We assembled first at the Cafe de la Regence.... The Monarch of the dinner-table seemed none the worse for his recent misadventures and showed no sign of bitterness, resentment or remorse. Surrounded by devout adherents, he repaid their hospitality by an easy flow of practised wit and wisdom, by which he seemed to amuse himself as much as anybody. The obligation of continual applause I, for one, found irksome. Never, I thought, had the face of praise looked more foolish."

Constance Wilde died on 7th April 1898. Wilde returned to his earlier religious beliefs and went to Rome and received the blessing of Leo XIII in April 1900. Suffering from meningitis he went to stay at the Hôtel d'Alsace. Before he became unconscious he remarked: "I am dying beyond my means". An Irish priest, Cuthbert Dunne, obtained by Robert Ross, gave him extreme unction and absolution on 29th November, 1900. Oscar Wilde died the next day and was buried in the Cimetière de Bagneux outside Paris.

In 1911 the publisher Martin Secker commissioned Arthur Ransome to write a book on Oscar Wilde. He was given considerable help by Wilde's literary executor, Robert Ross. He provided access not only to Wilde's literary estate, but also to his own private correspondence. Ross wanted Ransome's book to help rehabilitate Wilde's reputation. Ross also wanted to gain revenge on Lord Alfred Douglas, who he considered had destroyed Wilde. He did this by letting Ransome see the unabridged copy of De Profundis, the letter Wilde wrote to Douglas when he was in Reading Prison. Ransome became only the fourth person to read the letter where Wilde accused Douglas of vanity, treachery and cowardice.

The book, Wilde: A Critical Study, was published on 12th February 1912. The following month, on 9th March, Lord Douglas filed an action for libel against Ransome and Secker. Ransome's friends, Edward Thomas, John Masefield, Lascelles Abercrombie and Cecil Chesterton gave him support and Robin Collingwood offered to pay his legal costs. Secker settled out of court and sold the copyright of the book to Methuen.

The case against Ransome began in the High Court on 17th April 1913. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "Douglas had a strong case. Answering the charge that his client had ruined Wilde, the prosecution pointed out that Douglas was little more than a boy when Wilde first met him, whereas Wilde, almost twenty years his senior, had already written The Picture of Dorian Grey, a scandalous work sprung from a corner of life no proper gentleman ever visited, still less boasted of in print. If there had been any corruption, it had been Wilde's corruption of Douglas."

Douglas's counsel went on to argue that Wilde was "a shameless predator who had deprived an innocent boy not only of his inheritance, but of his chastity". Douglas admitted during cross-examination by J. H. Campbell (later Lord Chief Justice of Ireland) that he had deserted Wilde before his original conviction and had not returned to England, let alone visited his friend in prison, in over two years. He also read out correspondence that indicated that Douglas had "consorted with male prostitutes" and had taken money from Wilde, not because he needed it but because it gave him an erotic thrill. Campbell read from a letter written by Douglas: "I remember the sweetness of asking Oscar for money. It was a sweet humiliation."

The case took a dramatic turn when the De Profundis letter was read out in court. It has been described as the "most devastating character assassination in the whole of literature". According to Wilde's letter, Douglas's insatiable appetite, vanity and ingratitude were responsible for every catastrophe. Wilde finished the letter with the words: "But most of all I blame myself for the entire ethical degradation I allowed you to bring on me. The basis of character is will power, and my will became utterly subject to yours. It sounds a grotesque thing to say, but it is none the less true. It was the triumph of the smaller over the bigger nature. It was the case of that tyranny of the weak over the strong which somewhere in one of my plays I describe as being the only tyranny that lasts."

Douglas, who claimed never to have read the letter, found the contents so upsetting he left the witness box, only to be called back and reprimanded by the judge. After a three-day trial, the jury took just over two hours to return its verdict. Arthur Ransome was found not guilty of libel and the publicity the book received meant that it was now going to be a bestseller. In spite of the ruling in his favour, Ransome insisted that the offending passages be deleted from every future edition of the book.

In another court-case in 1918, Alfred Douglas was asked if he regretted meeting Oscar Wilde. He replied: "I do most intensely... I think he had a diabolical influence on everyone he met. I think he is the greatest force for evil that has appeared in Europe during the last 350 years... He was the agent of the devil in every possible way. He was a man whose whole object in life was to attack and to sneer at virtue, and to undermine it in every way by every possible means, sexually and otherwise."

Primary Sources

(1) Frank Harris, My Life and Loves (1922)

Oscar Wilde's humor was an extraordinary gift and sprang to show on every occasion. Whenever I meet anyone who knew Oscar Wilde at any period of his life, I am sure to hear a new story on him - some humorous or witty thing he has said...

I have often been asked since to compare Oscar's humor with Shaw's. I have never thought Shaw humorous in conversation. It was on the spur of the moment that Oscar's humor was so extraordinary, and it was this spontaneity that made him so wonderful a companion. Shaw's humor comes from thought and the intellectual angle from which he sees things, a dry light thrown on our human frailties.

If you praised anyone enthusiastically or overpraised him, Oscar's humor took on a keener edge. I remember later praising something Shaw had written about this time, and I added, "The curious thing is, he seems to have no enemies."

"Not prominent enough yet for that, Frank," said Oscar. "Enemies come with success; but then you must admit that none of Shaw's friends like him," and he laughed delightfully. Ah, the dear London days when meeting Wilde had always an effect of sunshine in the mist!

(2) Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891)

Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man's original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion. Sometimes the poor are praised for being thrifty. But to recommend thrift to the poor is both grotesque and insulting. It is like advising a man who is starving to eat less. For a town or country labourer to practise thrift would be absolutely immoral. Man should not be ready to show that he can live like a badly fed animal. Agitators are a set of interfering, meddling people, who come down to some perfectly contented class of the community, and sow the seeds of discontent amongst them. That is the reason why agitators are so absolutely necessary. Without them, in our incomplete state, there would be no advance towards civilization.

(3) Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891)

In old days men had the rack. Now they have the press. That is an improvement certainly. But still it is very bad, wrong, and demoralizing. Somebody - was it Burke? - called journalism the fourth estate. That was true at the time, no doubt. But at the present moment it really is the only estate. It has eaten up the other three. The Lords Temporal say nothing, the Lords Spiritual have nothing to say, and the House of Commons has nothing to say and says it. We are dominated by Journalism.

(4) Charles Whibley, The Scots Observer (5th July 1890)

Why go grubbing in muck heaps? The world is fair, and the proportion of healthy-minded men and honest women to those that are foul, fallen and unnatural, is great. Mr Oscar Wilde has again been writing stuff that were better unwritten; and while The Picture of Dorian Gray, which he contributes to Lippincott's is ingenious, interesting, full of cleverness, and plainly the work of a man of letters, it is false art - for its interest is medico-legal; it is false to human nature - for its hero is a devil; it is false to morality - for it is not made sufficiently clear that the writer does not prefer a course of unnatural iniquity to a life of cleanliness, health and sanity. The story which deals with matters fitted only for the Criminal Investigation Department or a hearing in camera is discreditable alike to author and editor. Mr Wilde has brains, and art, and style; but if he can write for none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys, the sooner he takes to tailoring (or some other decent trade) the better for his own reputation and the public morals.

(5) Harford Montgomery Hyde, Oscar Wilde (1976)

The reference to the noblemen and the telegraph-boys, concerned in the so-called Cleveland Street scandal, was particularly offensive. The scandal involved two ducal offspring, Lord Arthur Somerset and the Earl of Euston, who were said to have frequented a homosexual brothel off the Tottenham Court Road, where telegraph-boys from the General Post Office were able to earn additional money by going to bed with the Cleveland Street establishment's aristocratic customers." There is no evidence that Wilde ever went to the house in Cleveland Street, but Henley may have thought that he did so or at least had been active in a homosexual circle, since the editor, who had evidently heard some gossip, is on record as having asked Whibley what was the nature of "this dreadful scandal about Mr Oscar Wilde."

(6) Oscar Wilde, letter to William Ernest Henley (July 1890)

Your reviewer suggests that I do not make it sufficiently clear whether I prefer virtue to wickedness or wickedness to virtue. An artist, sir, has no ethical sympathies at all. Virtue and wickedness are to him simply what the colours on his palette are to the painter. They are no more, and they are no less. He sees that by their means a certain artistic effect can be produced and he produces it. Iago may be morally horrible and Imogen stainlessly pure. Shakespeare, as Keats said, had as much delight in creating the one as he had in creating the other.

(7) William Ernest Henley, letter to Oscar Wilde (July 1890)

It was not to be expected that Mr Wilde would agree with his reviewer as to the artistic merits of his booklet. Let it be conceded to him that he has succeeded in surrounding his hero with such an atmosphere as he describes. That is his reward. It is none the less legitimate for a critic to hold and express the opinion that no treatment, however skilful, can make the atmosphere tolerable to his readers. That is his punishment. No doubt it is the artist's privilege to be nasty; but he must exercise that privilege at his peril.

(8) Walter Pater, The Bookman (April, 1891)

There is always something of an excellent talker about the writing of Mr Oscar Wilde; and in his hands, as happens so rarely with those who practise it, the form of dialogue is justified by its being really alive. His genial, laughter-loving sense of life and its enjoyable intercourse, goes far to obviate any crudity there may be in the paradox, with which, as with the bright and shining truth which often underlies it, Mr Wilde, startling his "countrymen," carries on, more perhaps than any other writer, the brilliant critical work of Matthew Arnold...

Dorian himself, though certainly a quite unsuccessful experiment in Epicureanism, in life as a fine art, is (till his inward spoiling takes visible effect suddenly, and in a moment, at the end of his story) a beautiful creation. But his story is also a vivid, though carefully considered, exposure of the corruption of a soul, with a very plain moral pushed home, to the effect that vice and crime make people coarse and ugly.

(9) Oscar Wilde, letter to Alfred Douglas (August, 1894)

Yesterday (Sunday) Alphonso, Stephen and I sailed to Littlehampton in the morning, bathing on the way. We took five hours in an awful gale to come back and did not reach the pier till eleven o'clock at night, pitch dark all the way, and a fearful sea. I was drenched, but Viking-like and daring. It was, however, quite a dangerous adventure. All the fishermen were waiting for us. I flew to the hotel for hot brandy and water on landing with my companions... As it was past ten o'clock on a Sunday night the proprietor could not sell us any brandy or spirits of any kind! So he had to give it to us. The result was not displeasing, but what laws! A hotel proprietor is not allowed to sell necessary harmless' alcohol to three shipwrecked mariners, wet to the skin, because it is Sunday! Both Alphonso and Stephen are now anarchists, I need hardly say.

(10) Oscar Wilde, speech reported in The Worthing Gazette (19th September, 1894)

It (Worthing) has beautiful surroundings and lovely long walks, which I recommend to other people, but never take myself... To my mind few things are so important as the capacity to be amused, feeling pleasure, and giving it to others. For whenever a person is happy, he is good, although perhaps when he is good he is not always happy.

(11) Chris Hare, Worthing a History (2008)

Loud applause and laughter followed those remarks, though Wilde would doubtless have received a different response had the audience known the truth about his private life or the 'pleasures' he was indulging in with two local teenage boys.

Oscar Wilde was a great playwright and a man of considerable creative talents, but he also had a predilection for young men, indeed boys. At Worthing he befriended newspaper boy Alphonso Conway and his friend Stephen. Charges of gross indecency with Conway were added to the charge sheet at his trail the following year. Wilde is remembered today as a man persecuted by a harsh and unforgiving society, typified by the pugilistic Marquis of Queensberry, yet whether society even today would condone a middle-aged man of superior education seducing teenage boys of little education, is surely an open question. Wilde was in many ways emotionally a child himself, not thinking or considering the implications of his actions. He showered gifts on the two boys and took them on "adventures"; all of which he reported to Douglas in his usual effusive style.

(7) Oscar Wilde, cross-examined by Edward Clarke on 3rd April, 1895.

Edward Clarke: Did Lord Alfred Douglas go to Cairo then?

Oscar Wilde: Yes; in December, 1893.

Edward Clarke: On his return were you lunching together in the Cafe Royal when Lord Queensberry came in?

Oscar Wilde: Yes. He shook hands and joined us, and we chatted on perfectly friendly terms about Egypt and various other subjects.

Edward Clarke: Shortly after that meeting did you become aware that he was making suggestions with regard to your character and behaviour?

Oscar Wilde: Yes. Those suggestions were not contained in letters to me. At the end of June, 1894, there was an interview between Lord Queensberry and myself in my house. He called upon me, not by appointment, about four o'clock in the afternoon, accompanied by a gentleman with whom I was not acquainted. The interview took place in my library. Lord Queensberry was standing by the window. I walked over to the fireplace, and he said to me, "Sit down." I said to him, "I do not allow anyone to talk like that to me in my house or anywhere else. I suppose you have come to apologize for the statement you made about my wife and myself in letters you wrote to your son. I should have the right any day I chose to prosecute you for writing such a letter." He said, "The letter was privilegcd, as it was written to my son." I said, "How dare you say such things to me about your son and me?" He said, "You were both kicked out of the Savoy Hotel at a moment's notice for your disgusting conduct." I said, "That is a lie." He said, "You have taken furnished rooms for him in Piccadilly." I said, "Somebody has been telling you an absurd set of lies about your son and me. I have not done anything of the kind." He said, "I hear you were thoroughly well blackmailed for a disgusting letter you wrote to my son." I said, "The letter was a beautiful letter, and I never write except for publication." Then I asked: "Lord Queensberry, do you seriously accuse your son and me of improper conduct?" He said, "I do not say that you are it, but you look it." (Laughter.)

Justice Collins: I shall have the Court cleared if I hear the slightest disturbance again.

Oscar Wilde: "But you look it, and you pose as it, which is just as bad. If I catch you and my son together again in any public restaurant I will thrash you." I said, "I do not know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot at sight." I then told Lord Queensberry to leave my house. He said he would not do so. I told him that I would have him put out by the police. He said, "It is a disgusting scandal." I said, "If it be so, you are the author of the scandal, and no one else." I then went into the hall and pointed him out to my servant. I said, "This is the Marquess of Queensberry, the most infamous brute in London. You are never to allow him to enter my house again." It is not true that I was expelled from the Savoy Hotel at any time. Neither is it true that I took rooms in Piccadilly for Lord Queensberry's son. I was at the theatre on the opening night of the play, The Importance of Being Earnest, and was called before the curtain. The play was successful. Lord Queensberry did not obtain admission to the theatre. I was acquainted with the fact that Lord Queensberry had brought a bunch of vegetables with him.

Edward Clarke: When was it you heard the first statement affecting your character?

Oscar Wilde: I had seen communications from Lord Queensberry, not to his son, but to a third party--members of his own and of his wife's families. I went to the Albemarle Club on the 28th of February and received from the porter the card which has been produced. A warrant was issued on the 1st of March.

(8) Oscar Wilde, speech in court (April, 1895).

The "Love that dare not speak its name" in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michaelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michaelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the "Love that dare not speak its name," and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.

(12) Max Beerbohm, letter to Reginald Turner (April, 1895).

Oscar has been quite superb. His speech about the Love that dares not tell his name was simply wonderful and carried the whole court right away, quite a tremendous burst of applause. Here was this man, who had been for a month in prison and loaded with insults and crushed and buffeted, perfectly self-possessed, dominating the Old Bailey with his fine presence and musical voice. He has never had so great a triumph, I am sure as when the gallery burst into applause - I am sure it affected the jury.

(13) Edward Clarke, statement to the court in May, 1895.

I suggest to you, gentlemen, that your duty is simple and clear and that when you find a man who is assailed by tainted evidence entering the witness-box, and for a third time giving a clear, coherent and lucid account of the transactions, such as that which the accused has given to-day, I venture to say that that man is entitled to be believed against a horde of blackmailers such as you have seen.... this matter. I know not on what grounds the course has been taken. . . .

This trial seems to be operating as an act of indemnity for all the blackmailers in London. Wood and Parker, in giving evidence, have established for themselves a sort of statute of limitations. In testifying on behalf of the Crown they have secured immunity for past rogueries and indecencies. It is on the evidence of Parker and Wood that you are asked to condemn Mr. Wilde. And, Mr. Wilde knew nothing of the characters of these men. They were introduced to him, and it was his love of admiration that caused him to be in their society. The positions should really be changed. It is these men who ought to be the accused, not the accusers. It is true that Charles Parker and Wood never made any charge against Mr. Wilde before the plea of justification in the libel case was put in - but what a powerful piece of evidence that is in favour of Mr. Wilde! For if Charles Parker and Wood thought they had material for making a charge against Mr. Wilde before that date, do you not think, gentlemen, they would have made it? Do you think that they would have remained year after year without trying to get something from him? But Charles Parker and Wood previously made no charge against Mr. Wilde, nor did they attempt to get money from him, and that circumstance is one among other cogent proofs to be found in the case that there is no truth whatever in the accusations against Mr. Wilde....

You must not act upon suspicion or prejudice, but upon an examination of the facts, gentlemen, and on the facts, I respectfully urge that Mr. Wilde is entitled to claim from you a verdict of acquittal. If on an examination of the evidence you, therefore, feel it your duty to say that the charges against the prisoner have not been proved, then I am sure that you will be glad that the brilliant promise which has been clouded by these accusations, and the bright reputation which was so nearly quenched in the torrent of prejudice which a few weeks ago was sweeping through the press, have been saved by your verdict from absolute ruin; and that it leaves him, a distinguished man of letters and a brilliant Irishman, to live among us a life of honour and repute, and to give in the maturity of his genius gifts to our literature, of which he has given only the, promise in his early youth.

(14) Oscar Wilde, De Profundis (1897)

I was a man who stood in symbolic relations to the art and culture of my age. I had realised this for myself at the very dawn of my manhood, and had forced my age to realise it afterwards. Few men hold such a position in their own lifetime, and have it so acknowledged. It is usually discerned, if discerned at all, by the historian, or the critic, long after both the man and his age have passed away. With me it was different. I felt it myself, and made others feel it. Byron was a symbolic figure, but his relations were to the passion of his age and its weariness of passion. Mine were to something more noble, more permanent, of more vital issue, of larger scope.

The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flaneur, a dandy, a man of fashion. I surrounded myself with the smaller natures and the meaner minds. I became the spendthrift of my own genius, and to waste an eternal youth gave me a curious joy. Tired of being on the heights, I deliberately went to the depths in the search for new sensation. What the paradox was to me in the sphere of thought, perversity became to me in the sphere of passion. Desire, at the end, was a malady, or a madness, or both. I grew careless of the lives of others. I took pleasure where it pleased me, and passed on. I forgot that every little action of the common day makes or unmakes character, and that therefore what one has done in the secret chamber one has some day to cry aloud on the housetop. I ceased to be lord over myself. I was no longer the captain of my soul, and did not know it. I allowed pleasure to dominate me. I ended in horrible disgrace. There is only one thing for me now, absolute humility.

I have lain in prison for nearly two years. Out of my nature has come wild despair; an abandonment to grief that was piteous even to look at; terrible and impotent rage; bitterness and scorn; anguish that wept aloud; misery that could find no voice; sorrow that was dumb. I have passed through every possible mood of suffering....

I hope to live long enough and to produce work of such a character that I shall be able at the end of my days to say, "Yes! this is just where the artistic life leads a man!" Two of the most perfect lives I have come across in my own experience are the lives of Verlaine and of Prince Kropotkin: both of them men who have passed years in prison: the first, the one Christian poet since Dante; the other, a man with a soul of that beautiful white Christ which seems coming out of Russia. And for the last seven or eight months, in spite of a succession of great troubles reaching me from the outside world almost without intermission, I have been placed in direct contact with a new spirit working in this prison through man and things, that has helped me beyond any possibility of expression in words: so that while for the first year of my imprisonment I did nothing else, and can remember doing nothing else, but wring my hands in impotent despair, and say, "What an ending, what an appalling ending!" now I try to say to myself, and sometimes when I am not torturing myself do really and sincerely say, "What a beginning, what a wonderful beginning!" It may really be so. It may become so. If it does I shall owe much to this new personality that has altered every man's life in this place...

A great friend of mine - a friend of ten years' standing - came to see me some time ago, and told me that he did not believe a single word of what was said against me, and wished me to know that he considered me quite innocent, and the victim of a hideous plot. I burst into tears at what he said, and told him that while there was much amongst the definite charges that was quite untrue and transferred to me by revolting malice, still that my life had been full of perverse pleasures, and that unless he accepted that as a fact about me and realised it to the full I could not possibly be friends with him any more, or ever be in his company. It was a terrible shock to him, but we are friends, and I have not got his friendship on false pretences....

All trials are trials for one's life, just as all sentences are sentences of death; and three times have I been tried. The first time I left the box to be arrested, the second time to be led back to the house of detention, the third time to pass into a prison for two years. Society, as we have constituted it, will have no place for me, has none to offer; but Nature, whose sweet rains fall on unjust and just alike, will have clefts in the rocks where I may hide, and secret valleys in whose silence I may weep undisturbed. She will hang the night with stars so that I may walk abroad in the darkness without stumbling, and send the wind over my footprints so that none may track me to my hurt: she will cleanse me in great waters, and with bitter herbs make me whole.

(15) Augustus John, Chiaroscuro (1954)

Rothenstein proposed a visit to Paris where he (Oscar Wilde) was to be found. Accordingly, the Vattetot expedition concluded, Will and Alice Rothenstein, Charles Conder and myself proceeded thither to pass a week or two, largely in the company of the distinguished reprobate. I had heard a lot about Oscar, of course, and on meeting him was not in the least disappointed, except in one respect: prison discipline had left one, and apparently only one, mark on him, and that not irremediable: his hair was cut short... We assembled first at the Cafe de la Regence. Warmed up with a succession of Maraschinos, the Master began to coruscate genially. I could only listen in respectful silence, for did I not know that "little boys should be obscene and not heard"? In any case I could think of nothing whatever to say. Even my laughter sounded hollow. The rest of the company, better trained, were able to respond to the Master's sallies with the proper admixture of humorous deprecation and astonishment: "My dear Oscar..!" Conder alone behaved improperly, pouring his wine into his soup and so forth, and drawing upon himself a reproof: "Vine leaves in the hair should be beautiful, but such childish behaviour is merely tiresome." When Alice Rothenstein, concerned quite unnecessarily for my reputation, persuaded me to visit a barber, Oscar, on seeing me the next day, looked very grave: laying his hand on my shoulder, "You should have consulted me," he said, "before taking this important step." Although I found Oscar thoroughly amiable, I got bored with these seances and especially with the master's entourage, and was always glad to retire from the rather oppressive company of the uncaged and now maneless lion, to seek with Conder easier if less distinguished company.

The Monarch of the dinner-table seemed none the worse for his recent misadventures and showed no sign of bitterness, resentment or remorse. Surrounded by devout adherents, he repaid their hospitality by an easy flow of practised wit and wisdom, by which he seemed to amuse himself as much as anybody. The obligation of continual applause I, for one, found irksome. Never, I thought, had the face of praise looked more foolish.

Wilde seemed to be an easy-going sort of genius, with an enormous sense of fun, infallible bad taste, gleams of profundity and a romantic apprehension of the Devil. A great man of inaction, he showed, I think, sound judgment when in his greatest dilemma he chose to sit tight (in every sense) and await the police, rather than face freedom in the company of Frank Harris, who had a yacht with steam up waiting for him down the Thames. I enjoyed his elaborate jokes, had found his De Profundis sentimental and false, the Reading Ballad charming and ingenious, and The Importance of Being Earnest about perfect. When I read The Picture of Dorian Gray as a boy, it made a powerful and curiously unpleasant impression on me, but on re-reading it since, I found it highly entertaining. By that time it had become delightfully dated.

(15) Oscar Wilde, quotations (1875-1898)

Pleasure is the only thing one should live for. Nothing ages like happiness.

Friendship is so more tragic than love. It lasts longer.

One should always play fairly when one has the winning cards.

The old believe everything. The middle-aged suspect everything. The young know everything.

Always forgive your enemies - nothing annoys them so much.

Selfishness is not living as one wishes to live, it is asking others to live as one wishes to live.

Life is not a romance; one has romantic memories and romantic hopes – that’s all. Our most burning ecstasies are merely the shadows of what we have felt elsewhere or of what we hope to feel someday.

When I was young I thought that money was the most important thing in life; now that I am old I know that it is.

Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught.

Women are made to be loved, not understood.

Children begin by loving their parents; after a time they judge them; rarely, if ever, do they forgive them.

To love oneself is the beginning of a lifelong romance.

Art is the most intense mode of individualism that the world has known.

We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.

All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That's his.

Woman begins by resisting a man's advances and ends by blocking his retreat.

There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.

In America the President reigns for four years, and Journalism governs forever and ever.

Whenever people agree with me I always feel I must be wrong.

What is a cynic? A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.

Men always want to be a woman's first love - women like to be a man's last romance.

Some cause happiness wherever they go; others whenever they go.

An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.

I can resist everything except temptation.

America is the only country that went from barbarism to decadence without civilization in between.

The difference between literature and journalism is that journalism is unreadable and literature is not read.