Frank Harris

James Thomas (Frank) Harris, the third son and fourth of the five children of Thomas Vernon Harris (1814–1899), a mariner, and his wife, Anne (1816–1859), was probably born on 14th February 1856, in Galway. According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "He endured a mean, miserable, and loveless childhood, in which he resented alike the puritanical severity of his father and the discipline of his masters at the Royal School in Armagh and, later, Ruabon Grammar School in Denbighshire (1869–71)"

Harris wrote about his time at Ruabon Grammar School in his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922): "The English are proud of the fact that they hand a good deal of the school discipline to the older boys: they attribute this innovation to Arnold of Rugby and, of course, it is possible, if the supervision is kept up by a genius, that it may work for good and not for evil; but usually it turns the school into a forcing-house of cruelty and immorality. The older boys establish the legend that only sneaks would tell anything to the masters, and they are free to give rein to their basest instincts."

Harris emigrated to the United States in 1871 and went to live with his brother in Lawrence, Kansas. He enrolled at the University of Kansas in 1874 and passed the Douglas County bar examinations in 1875. He then moved to Brighton and became a French tutor at Brighton College. Harris married Florence Ruth (1852–1879) in Paris, on 17th October 1878. On her death of tuberculosis ten months later, he moved to London where he attempted to make a living from journalism. He joined the Social Democratic Federation where he made contact with H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillett.

In 1883 he was appointed editor of The London Evening News. By this time he had left the SDF but the newspaper did run several campaigns against poverty. Harris developed a reputation as being hostile to the aristocracy with his emphasis on society scandals. Michael Holroyd pointed out: "He (Harris) quadrupled its circulation by sending his journalists to the police courts, and startling his readers with alluring headlines, 'Extraordinary Charge Against a Clergyman and Gross Outrage on a Female'. It was Harris who had reported in scabrous detail the divorce case of Lady Colin Campbell, receiving an indictment for obscene libel that assisted the paper's Tory proprietor in dismissing him in 1886." Soon afterwards he became the editor of The Fortnightly Review.

Harris married Emily Clayton on 2nd November 1887. She was the widow of Thomas Greenwood Clayton, a successful businessman. He intended to use her fortune of £90,000 to launch his political career. He joined the Conservative Party and became the prospective candidate in South Hackney. However, he withdrew his candidature in 1891, after supporting Charles Stewart Parnell in the O'Shea divorce. Harris was a well-known womaniser and his wife left him in 1894.

Harris appointed George Bernard Shaw and Max Beerbohm as drama critics for The Fortnightly Review. He also published long articles by Shaw (Socialism and Superior Brains) and Oscar Wilde (The Soul of Man Under Socialism) about socialism. Harris also continued to campaign against the aristocracy and financial corruption. This made him many enemies and in 1894 he was sacked by Frederick Chapman, the owner of the journal, for publishing an article by Charles Malato, an anarchist who praised political murder as "propaganda… by deed".

Harris now purchased The Saturday Review. The author, H.G. Wells, got to know him during this period: "His dominating way in conversation startled, amused and then irritated people. That was what he lived for, talking, writing that was loud talk in ink, and editing. He was a brilliant editor, for a time, and then the impetus gave out, and he flagged rapidly. So soon as he ceased to work vehemently he became unable to work. He could not attend to things without excitement. As his confidence went, he became clumsily loud."

Once again he appointed George Bernard Shaw as his drama critic on a salary of £6 a week. Shaw later commented that was "not bad pay in those days" and added that Harris was "the very man for me, and I the very man for him". Shaw's hostile reviews led to some managements withdrawing their free seats. Some of the book reviewers were so severe that publishers cancelled their advertisements. Harris was forced to sell the journal for financial reasons in 1898. Michael Holroyd has argued: "There had been a number of libel cases and rumours of blackmail - later put down by Shaw to Harris's innocence of English business methods."

Margot Asquith and Herbert Henry Asquith also met him at this time. Margot recalled in her autobiography: "He sat like a prince - with his sphinx-like imperviousness to bores - courteous and concentrated on the languishing conversation. I made a few gallant efforts; and my husband, who is particularly good on these self-conscious occasions, did his best... but to no purpose."

According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines, Harris had a complicated sex life: "In 1898 Harris was maintaining a ménage at St Cloud with an actress named May Congden, with whom he had a daughter, together with a house at Roehampton containing Nellie O'Hara, with whom he possibly also had a daughter (who died young). He seems to have had other daughters with different women. O'Hara was his helpmate and âme damnée for over thirty years. Apparently the natural daughter of Mary Mackay and a drunkard named Patrick O'Hara, she was a clumsy schemer, battening onto Harris in the hope of millions but encouraging him in self-destructive and rascally courses."

Frank Harris became friends with several leading literary figures, including George Meredith, Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater. In his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922), Harris recalled that: "One day in 1890 I had George Meredith, Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde dining with me in Park Lane and the time of sex-awakening was discussed. Both Pater and Wilde spoke of it as a sign of puberty. Pater thought it began about thirteen or fourteen and Wilde to my amazement set it as late as sixteen. Meredith alone was inclined to put it earlier."

In 1900 Frank Harris had a book of short stories, Montes the Matador, published. Later that year, his first play, Mr and Mrs Daventry, was produced. The play, that dealt with adultery and sexually emancipated women, was described by Gerald du Maurier, as "the most daring and naturalistic production of the modern English stage… at once repellent and fantastic". His novel, The Bomb, about anarchism set in Chicago, appeared in 1908. The reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement called it a "highly charged with an explosive blend of socialistic and anarchistic matter, wrapped in a gruesome coating of exciting fiction… crowded with swindled workmen, callous employers, brutal police, inhuman millionaires". This was followed by three works about William Shakespeare, entitled The Man Shakespeare (1909), Shakespeare and his Love (1910) and The Women of Shakespeare (1911).

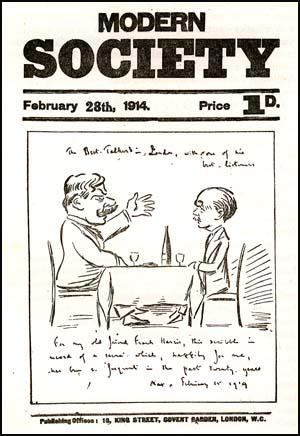

In August 1913, Harris began a magazine entitled, Modern Society. He employed Enid Bagnold as a staff writer. She later recalled: "He was an extraordinary man. He had an appetite for great things and could transmit the sense of them. He was more like a great actor than a man of heart. He could simulate anything. While he felt admiration he could act it, and while he acted it, he felt it. And greatness being his big part, he hunted the centuries for it, spotting it in literature, in passion, in action." She added: "His theory was that women love ugly men. He made sin seem glorious. He was surrounded by rascals. It was better than meeting good men. The wicked have such glamour for the young."

In Bagnold's Autobiography (1917) she admitted that Harris took her virginity. "The great and terrible step was taken... I went through the gateway in an upper room in the Cafe Royal. That afternoon at the end of the session I walked back to Uncle Lexy's at Warrington Crescent, reflecting on my rise. Like a corporal made sergeant.... And what about love - what about the heart? It wasn't involved. I went through this adventure like a boy, in a merry sort of way, without troubling much. I didn't know him. If I had really known him I might have been tender." During dinner with Uncle Lexy she later wrote that she couldn't believe that her skull wasn't chanting aloud: "I'm not a virgin! I'm not a virgin".

Beerbohm wrote: "The Best Talker in London, with one of his best listeners".

In February 1914 Harris was sent to Brixton Prison for contempt of court following an article on Earl Fitzwilliam, who had been cited as a co-respondent in a divorce case. On his release he moved to New York City. In 1915 he published Contemporary Portraits. The following year he published a biography of Oscar Wilde. Harris also wrote extensively about the First World War. He was highly critical of the way the war was being fought and some of these were described as "traitorious". He also predicted that Germany would win the war. These articles appeared as England or Germany? (1915). In 1916 he became editor of Pearson's Magazine. According to his biographer, Richard Davenport-Hines: "He (Harris) repeatedly clashed with American censorship and made many enemies with his rude, unpredictable, and arrogant conduct."

Harris now moved to Nice. After the death of his second wife he married Nellie O'Hara. Harris's response to becoming sexually impotent was to write an autobiography about his sex life. Harris told George Bernard Shaw: "I am going to see if a man can tell the truth naked and unashamed about himself and his amorous adventures in the world." The first volume of My Life and Loves was published in 1922. The first volume was burnt by customs officials and the second volume resulted in him being charged with corrupting public morals.

In 1928 Harris wrote to Shaw asking if he could write his biography. Shaw replied: "Abstain from such a desperate enterprise... I will not have you write my life on any terms." Harris was convinced that the royalties of the proposed book would solve his financial problems. In 1929 he wrote: "You are honoured and famous and rich - I lie here crippled and condemned and poor."

Eventually, George Bernard Shaw agreed to cooperate with Harris in order to help him provide for his wife. Shaw told a friend that he had to agree because "Frank and Nellie... were in rather desperate circumstances." Shaw warned Harris: "The truth is I have a horror of biographers... If there is one expression in this book of yours that cannot be read at a confirmation class, you are lost for ever. " He sent Harris contradictory accounts of his life. He told Harris that he was "a born philanderer". On another occasion he attempted to explain why he had little experience of sexual relationships. In 1930 he wrote to Harris: "If you have any doubts as to my normal virility, dismiss them from your mind. I was not impotent; I was not sterile; I was not homosexual; and I was extremely susceptible, though not promiscuously."

Frank Harris died of heart failure on 26th August 1931. Shaw sent Nellie a cheque and she arranged to send him the galley-proofs. The book was then rewritten by Shaw: "I have had to fill in the prosaic facts in Frank's best style, and fit them to his comments as best I could; for I have most scrupulously preserved all his sallies at my expense.... You may, however, depend on it that the book is not any the worse for my doctoring." George Bernard Shaw was published in 1932.

Primary Sources

(1) Frank Harris, My Life and Loves (1922)

All English school life was summed up for me in the "fagging." ... The fags' names on duty were put up on a blackboard, and if you were not on time, ay, and servile to boot, you'd get a dozen from an ash plant on your behind, and not laid on perfunctorily and with distaste, as the Doctor did it, but with vim, so that I had painful weals on my backside and couldn't sit down for days without a smart.

The fags, too, being young and weak, were very often brutally treated just for fun. On Sunday mornings in summer, for instance, we had an hour longer in bed. I was one of the half-dozen juniors in the big bedroom; there were two older boys in it, one at each end, presumably to keep order; but in reality to teach lechery and corrupt their younger favorites. If the mothers of England knew what goes on in the dormitories of these boarding schools throughout England, they would all be closed, from Eton and Harrow, upwards or downwards, in a day. If English fathers even had brains enough to understand that the fires of sex need no stoking in boyhood, they, too, would protect their sons from the foul abuse. But I shall come back to this. Now I wish to speak of the cruelty.

Every form of cruelty was practiced on the younger, weaker and more nervous boys. I remember one Sunday morning the half-dozen older boys pulled one bed along the wall and forced all seven younger boys underneath it, beating with sticks any hand or foot that showed. One little fellow cried that he couldn't breathe, and at once the gang of tormentors began stuffing up all the apertures, saying that they would make a "Black Hole" of it. There were soon cries and strugglings under the bed, and at length one of the youngest began shrieking, so that the torturers ran away from the prison, fearing lest some master should hear.

One wet Sunday afternoon in midwinter, a little nervous "mother's darling" from the West Indies, who always had a cold and was always sneaking near the fire in the big schoolroom, was caught by two of the fifth and held near the flames. Two more brutes pulled his trousers tight over his bottom, and the more he squirmed and begged to be let go, the nearer the flames he was pushed, till suddenly the trousers split apart scorched through; and as the little fellow tumbled forward screaming, the torturers realized that they had gone too far. The little "nigger," as he was called, didn't tell how he came to be so scorched but took his fortnight in sick bay as a respite.

We read of a fag at Shrewsbury who was thrown into a bath of boiling water by some older boys because he liked to take his bath very warm; but this experiment turned out badly, for the little fellow died and the affair could not be hushed up, though it was finally dismissed as a regrettable accident.

The English are proud of the fact that they hand a good deal of the school discipline to the older boys: they attribute this innovation to Arnold of Rugby and, of course, it is possible, if the supervision is kept up by a genius, that it may work for good and not for evil; but usually it turns the school into a forcing-house of cruelty and immorality. The older boys establish the legend that only sneaks would tell anything to the masters, and they are free to give rein to their basest instincts.

(2) Enid Bagnold, Autobiography (1917)

He (Frank Harris) was an extraordinary man. He had an appetite for great things and could transmit the sense of them. He was more like a great actor than a man of heart. He could simulate anything. While he felt admiration he could act it, and while he acted it, he felt it. And greatness being his big part, he hunted the centuries for it, spotting it in literature, in passion, in action...

For what happened, of course, was totally to be foreseen. The great and terrible step was taken. What else could you expect from a girl so expectant? "Sex," said Frank Harris, "is the gateway to life." So I went through the gateway in an upper room in the Cafe Royal.

That afternoon at the end of the session I walked back to Uncle Lexy's at Warrington Crescent, reflecting on my rise. Like a corporal made sergeant.

As I sat at dinner with Aunt Clara and Uncle Lexy I couldn't believe that my skull wasn't chanting aloud: "I'm not a virgin! I'm not a virgin".

It was a boy's cry of initiation - not a girl's.

And what about love - what about the heart? It wasn't involved. I went through this adventure like a boy, in a merry sort of way, without troubling much. I didn't know him. If I had really known him I might have been tender.

"In love" doesn't make one tender. It makes one furious or jealous, or miserable when it stops. It's the years that make one tender. Time, affection, knowledge. "In love" is the reverse of knowledge.

I went home every week-end. Once home it seemed it hadn't happened. Lies were told. You can't grow up without lies. A child is so much older than her mother thinks she is. I risked so much. It was their happiness I risked: not mine. Nothing could have foundered me - I thought. But if they had known (that's what I risked) could things ever have been the same?

There was plenty to tell at week-ends, without thinking of sex. The office was so thunderingly alive, F.H. in and out, struggling in despair, or blazingly optimistic.

(3) Walter L. George, A Novelist on Novels (1918)

If a novelist were to develop his characters evenly, the three-hundred-page novel might extend to five hundred, the additional two hundred pages would be made up entirely of the sex preoccupations of the characters. There would be as many scenes in the bedroom as in the drawing room, probably more, as more time is passed in the sleeping apartment. The additional two hundred pages would offer pictures of the sex side of the characters and would compel them to become alive: at present they often fail to come to life because they only develop, say, five sides out of six.... Our literary characters are lop-sided because their ordinary traits are fully portrayed while their sex life is cloaked, minimized or left out.... Therefore the characters in modern novels are all false. They are megalocephalous and emasculate. English women speak a great deal about sex... It is a cruel position for the English novel. The novelist may discuss anything but the main preoccupation of life... we are compelled to pad out with murder, theft and arson which, as everybody knows, are perfectly moral things to write about.

(4) Enid Bagnold, The Sunday Times (8th February, 1959)

The parts he played had one common link - they were all Great Parts. He was the Greatness-Spotter. And perhaps that was the strange elusive fragment that was real. He knew greatness when he saw it. He then sold it, pimped it, pawned it, wore it as his own, and while wearing it (playing the character of the "Character") he loved best what Simenon calls the "limit-moment".

He was en rapport with confession-moments, agony-moments. He stood in the prison corridor while Wilde, in a white sweat of nerves, changed his shoes for the prison boots, he arranged for a yacht to lie off Dartford, and the terrible interview he had when Wilde refused to flee before the trial so tore my heart that I could tell my grandchildren I was there myself.

But then, too, I was with him at the Last Supper - broken and astounded by the words of Jesus Christ. I waited with Mary Fitton when Shakespeare was late for a love appointment and she in such a pain of impatience she didn't know she hadn't put on her dress.

What was fascinating to me in him? Everything, Everything one had to "get over" - to swallow. Even the ugliness. Besides, for ugliness, his theory was that women love ugly men. He made sin seem glorious. He was surrounded by rascals. It was better than meeting good men. The wicked have such glamour for the young.

If a doubt sneaked in he made the doubt glorious. Caught out in a lie he laughed his great laugh, and that had its dash.

But all the time he was a ship nose-down for disaster. He could pull the stars out of the sky but he flushed them down the drain. Yet what a talker! What an alchemist in drama - what a story-teller! It's as impossible to reconstruct the thrall as to call back the voice and powers of Garrick.