George Meredith

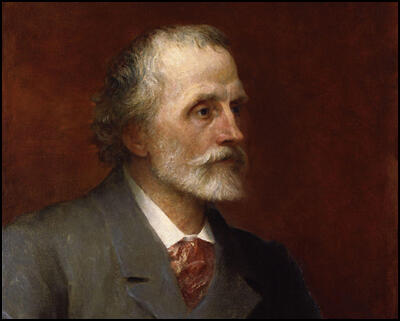

George Meredith, the only child of Augustus Urmston Meredith (1797–1876) and Jane Eliza Macnamara (1802–1833), was born at 73 High Street, Portsmouth on 12th February 1828. His mother died when he was five years old.

Meredith was educated at St Paul's School in Southsea and at a boarding-school in Suffolk. In August 1842 he was sent to a school in Neuwied near Koblenz. On his return to England he was articled to Richard Stephen Charnock, a London solicitor.

Meredith married a widow, Mary Ellen Nicolls (1821–1861) on 9th August 1849. Meredith had a strong interest in literature and had several articles published in Fraser's Magazine. In 1851 he published a volume of poems. His wife shared his literary interests but it was not a happy marriage. He later wrote "No sun warmed my roof-tree; the marriage was a blunder". Although his wife became pregnant more than once, only one child survived infancy, Arthur Meredith, born on 13th June 1853.

Meredith associated with a group of writers and artists. This included Henry Wallis and in 1855 he agreed to model for his famous painting, The Death of Chatterton. Soon afterwards, Meredith's wife began an affair with Wallis. She eventually left Meredith to live with Wallis.

Meredith published his first work of fiction, The Shaving of Shagpat: an Arabian Entertainment, in 1856. George Eliot described the book as "a work of genius". This was followed by Farina: a Legend of Cologne (1857). His novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel: a History of Father and Son (1859) was according to his biographer, Margaret Harris, "fuelled by the trauma of sexual betrayal." Meredith's next novel, Evan Harrington, was serialized in Once a Week magazine from February to October 1860.

At the time his work was considered to be similar to Charles Dickens. However, his books did not sell well and he was forced to became a publisher's reader for Chapman and Hall. It is claimed that he read about ten manuscripts a week. Meredith was the first to discover the talents of Thomas Hardy. After reading his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, he advised him to rewrite it as in its current state it would be perceived as "socialistic" or even "revolutionary" and that as a result would not be well-received by the critics. Meredith went on to argue that this might prove to be handicap to Hardy's future career. He suggested that Hardy should either rewrite the story or write another novel with a different plot.

Claire Tomalin, the author of Thomas Hardy: The Time Torn Man (2006) has pointed out: "George Meredith, a handsome man of forty in a frock coat, with wavy hair, moustache, and brown beard. At first Hardy did not realize he was the novelist, but he listened to his advice, which was that he would do better not to publish this book: it would certainly bring down attacks from reviewers and damage his future chances as a novelist." Hardy later reported that he appreciated Meredith's "trenchant" comments and that "he gave me no end of good advice, most of which, I am bound to say, he did not follow himself". With the help of Meredith the young novelist produced the best-selling Far From the Madding Crowd. Meredith also helped other young writers including Olive Schreiner and George Gissing, get their work published.

Meredith published Modern Love in 1862 deals with his relationship with his first wife who had died the previous year. Margaret Harris argues: "The fifty sixteen-line sonnets play out the end of a love affair in a narrative which dwells on representing states of mind and shifts of perception rather than on an objective account of what actually took place." Richard Holt Hutton, in his review of the book in The Spectator, suggested that: "Mr George Meredith is a clever man, without literary genius, taste or judgement." However, it received great praise from Algernon Charles Swinburne who claimed that Meredith is a poet "whose work, perfect or imperfect, is always as noble in design as it is often faultless in result".

Meredith met Marie Vulliamy (1840–1885) in 1863. He later wrote: "I knew when I spoke to her that hers was the heart I had long been seeking, and that my own in its urgency was carried on a pure though a strong tide". The couple married at Mickleham Parish Church on 20th September 1864. Marie gave birth to two children: William Maxse (1865) and Marie Eveleen (1871).

The journalist, Francis Burnand, was a close friend during this period. In his autobiography Records and Reminiscences (1904), he recalled: "George Meredith never merely walked, never lounged; he strode, he took giant strides. He had… crisp, curly, brownish hair, ignorant of parting; a fine brow, quick, observant eyes, greyish - if I remember rightly - beard and moustache, a trifle lighter than the hair. A splendid head; a memorable personality. Then his sense of humour, his cynicism, and his absolutely boyish enjoyment of mere fun, of any pure and simple absurdity. His laugh was something to hear; it was of short duration, but it was a roar; it set you off - nay, he himself, when much tickled, would laugh till he cried (it didn't take long to get to the crying), and then he would struggle with himself, hand to open mouth, to prevent another outburst."

Merediths purchased Flint Cottage, Box Hill, Dorking, in 1867. It was to remain their home for the rest of their lives. His next novel, The Adventures of Harry Richmond, illustrated by George Du Maurier, was serialised in The Cornhill Magazine from September 1870 to November 1871. This was followed by Beauchamp's Career, that was serialised in The Fortnightly Review from August 1874 to December 1875.

The writer Frank Harris became very close to Meredith. In his autobiography, My Life and Loves (1922), he explained how the relationship began: "I met him for the first time in Chapman's office - to me a most memorable experience. He was one of the handsomest men I have ever seen, a little above middle height, spare and nervous; a slendid head, all framed in silver hair; but perhaps because he was very deaf himself, he used to speak very loudly."

The short stories, The House on the Beach: a Realistic Tale, The Case of General Ople and Lady Camper, and The Tale of Chloe were published in the Quarterly Magazine. This was followed by his best known work, The Egoist: a Comedy in Narrative, that was serialized in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (June 1879 - Jan 1880). As Margaret Harris has pointed out: "Now acknowledged as his masterpiece, this highly structured novel both articulates Meredith's particular idea of comedy as ‘the ultimate civilizer’ and draws on the traditions of stage comedy of Molière and Congreve. While celebrating these various literary traditions, The Egoist also engages with such significant Victorian discourses as evolution and imperialism."

The poet James Thomson was a great supporter of Meredith's work. In an article on Meredith in May, 1876, he wrote: "His name and various passages in his works reveal Welsh blood, more swift and fiery and imaginative than the English.... So with his conversation. The speeches do not follow one another mechanically, adjusted like a smooth pavement for easy walking; they leap and break, resilient and resurgent, like running foam-crested sea-waves, impelled and repelled and crossed by under-currents and great tides and broad breezes; in their restless agitations you must divine the immense life abounding beneath and around and above them."

Frank Harris also thought highly of Meredith. He once told him "I look upon you as only second to the very greatest, to my heroes: Shakespeare, Goethe, and Cervantes." Harris said that Meredith turned away, perhaps to hide his emotion: "Strange, that is what I have sometimes thought of myself, but I never hoped to hear it said." Harris argued in his autobiography: "Meredith was the most interesting of companions. We agreed in almost everything but the flashes of his humour made his conversation entrancing."

Marie Meredith died on 17th September 1885, from cancer of the throat. George Meredith's health was also poor. He suffered from various gastric ailments and later developed from motor ataxia and osteoarthritis. He also had to endure increasing deafness. However, these problems did not stop him from writing and he published several novels including One of our Conquerors (1891), Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) and The Amazing Marriage (1895).

Meredith associated with several leading figures in the Liberal Party. This included Herbert Asquith, John Morley and Richard Haldane. Asquith later recalled: "It is true that his conversation, particularly as he grew deafer, tended to become a monologue, but it was sprinkled with gems and never bored. He was a great improvisatore and nothing could be more exhilarating than to watch him, with his splendid head and his eyes aflame, stamping up and down the room, while he extemporized at the top of his resonant voice a sonnet in perfect form on the governess's walking costume, or a dozen lines, in the blankest of Wordsworthian verse, in elucidation of Haldane's philosophy." On the left-wing of the party he was anti-imperialist and opposed the Boer War.

Meredith was also a supporter of women's suffrage and argued "that women have brains, and can be helpful to the hitherto entirely dominant muscular creature who has allowed them some degree of influence in return for servile flatteries and the graceful undulations of the snake admired yet dreaded".

The Common Cause, the journal of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, praised the work that Meredith had done in support of the campaign: "Beyond everything, what he brought to the younger generation of women was hope and self-revelation… Now woman feels that she belongs to herself, that she possesses herself, and that unless or until she does so the gift of herself is impossible. You cannot give what you have not got. Women … would force men to look at things as they are; at women's lives as they are; at the purely masculine world in which they are compelling women to live and to which the women cannot and ought not to adapt themselves."

Despite the support he gave to the NUWSS, he was opposed to the militant tactics of the Women's Social and Political Union and following a demonstration at the House of Commons he argued in a letter to The Times: "The mistake of the women has been to suppose that John Bull will move sensibly for a solitary kick". His views were dismissed by George Bernard Shaw who described Meredith as "a Cosmopolitan Republican Gentleman of the previous generation".

Frank Harris met him for the last time in the early months of 1909. Meredith told him: "People talk about me as if I were an old man. I don't feel old in the least. On the contrary, I do not believe in growing old, and I do not see any reason why we should ever die. I take as keen an interest in the movement of life as ever, I enter into the intrigues of parties with the same keen interest as of old. I have seen the illusion of it all, but it does not dull the zest with which I enter into it, and I hold more firmly than ever my faith in the constant advancement of the race. My eyes are as good as ever they were, only for small print I need to use spectacles. It is only in my legs that I feel weaker. I can no longer walk, which is a great privation to me. I used to be a keen walker; I preferred walking to riding; it sent the blood coursing to the brain; and besides, when I walked I could go through woods and footpaths which I could not have done if I had ridden. Now I can only walk about my own garden. It is a question of nerves. If I touch anything, however, slightly, I am afraid that I shall fall - that is my only loss. My walking days are over."

George Meredith died at home in Flint Cottage on 18th May, 1909.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Burnand, Records and Reminiscences (1904)

George Meredith never merely walked, never lounged; he strode, he took giant strides. He had… crisp, curly, brownish hair, ignorant of parting; a fine brow, quick, observant eyes, greyish - if I remember rightly - beard and moustache, a trifle lighter than the hair. A splendid head; a memorable personality. Then his sense of humour, his cynicism, and his absolutely boyish enjoyment of mere fun, of any pure and simple absurdity. His laugh was something to hear; it was of short duration, but it was a roar; it set you off - nay, he himself, when much tickled, would laugh till he cried (it didn't take long to get to the crying), and then he would struggle with himself, hand to open mouth, to prevent another outburst.

(2) James Thomson, George Meredith (May, 1876)

His name and various passages in his works reveal Welsh blood, more swift and fiery and imaginative than the English.... So with his conversation. The speeches do not follow one another mechanically, adjusted like a smooth pavement for easy walking; they leap and break, resilient and resurgent, like running foam-crested sea-waves, impelled and repelled and crossed by under-currents and great tides and broad breezes; in their restless agitations you must divine the immense life abounding beneath and around and above them.

(3) Herbert Henry Asquith, Memories and Reflections, 1852–1927 (1928)

"By God," said one of the Victorian wits to him one day, "George, why don't you write like you talk?" It is true that his conversation, particularly as he grew deafer, tended to become a monologue, but it was sprinkled with gems and never bored. He was a great improvisatore and nothing could be more exhilarating than to watch him, with his splendid head and his eyes aflame, stamping up and down the room, while he extemporized at the top of his resonant voice a sonnet in perfect form on the governess's walking costume, or a dozen lines, in the blankest of Wordsworthian verse, in elucidation of Haldane's philosophy.

(4) The Common Cause (27th May, 1909)

Beyond everything, what he brought to the younger generation of women was hope and self-revelation… Now woman feels that she belongs to herself, that she possesses herself, and that unless or until she does so the gift of herself is impossible. You cannot give what you have not got. Women … would force men to look at things as they are; at women's lives as they are; at the purely masculine world in which they are compelling women to live and to which the women cannot and ought not to adapt themselves.

(5) Frank Harris, My Life and Loves (1922)

I was more interested in Meredith than in any other man of my time. I thought him one of the greatest of men, worthy to stand with Shakespeare and Wordsworth. I knew him first just as I first knew Alfred Russel Wallace, through my connection with The Fortnightly Review and Mr. Chapman. He was one of the handsomest of men, just above middle height, slight and strong of figure with a superb head and face; the head all outlined in greying hair, but excellently shaped and the face noble: straight nose, incomparable blue eyes, now laughing, now pathetic, excellent mouth and chin-in fine a very good looking man, sane at once and strong. I have told elsewhere how Grant Allen sent him one of my earliest stories Montes, the Matador and how he praised it as better than the Carmen of Merimee because I had given even the bulls individuality: and he ended his praise with the words, "if there is any hand in England that can do better, I don't know it." As I have said somewhere, I regarded that judgment as my knighting. No contempt touched me afterwards; Meredith to me already stood among the greatest; indeed, I could never make out why, with all his gifts, he had not done a masterpiece.

Born in 1828, he brought out his first book of Poems in 1851, and I think he was always more of a poet than a prose-writer. But good as his best poetry is: even Love in the Valley has stanzas I can never forget and Modern Love with the entrancing "Margaret's Bridal Eve" is greater still; and just in the same way Richard Feverel comes near being the best conventional love-story in the language; and the later Diana of the Crossways is at least as admirable. Yet neither in poetry nor in prose has Meredith reached the highest or given his full measure.

The reason always escaped me. When I knew him first about 1885 he was the reader for Chapman and Hall and made his £500 or f£600 a year out of this easily enough while his books added perhaps as much more to his income. He had a house on Box Hill in Surrey and lived like a modest country gentleman; nothing in his circumstances hindered him from reaching Cervantes or Shakespeare.

And his conversation was astonishing; he touched every thing that came up from the highest stand-point... Meredith was the most interesting of companions. We agreed in almost everything but the flashes of his humor made his conversation entrancing. I still regard him with Russel Wallace as the wisest men I've ever met; but Wallace's belief in another and larger life after death shut him away from me, while Meredith's love of nature and his delight in nature-studies all appealed to me.