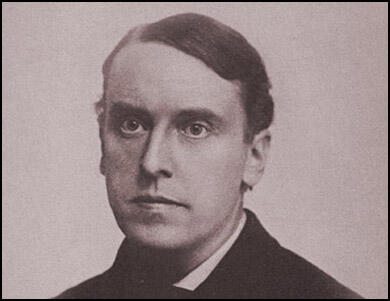

Edward Aveling

Edward Aveling, the son of a Congregational minister, was born in Stoke Newington, London, on 29th November, 1849. Aveling was educated at Harrow School and the Faculty of Medicine at University College, London. An excellent student and after he graduated he was appointed as a Lecturer in Comparative Anatomy at London Hospital.

Aveling was influenced by the theories of Charles Darwin and lost his religious beliefs. He joined the Secular Society and became friendly with Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant.

Aveling contributed articles on scientific subjects to Bradlaugh's journal, The National Reformer and wrote a book on evolution called The Student's Darwin (1881). Aveling's public statements on his atheism resulted in him being removed from his post at London Hospital.

Annie Besant was impressed by Aveling's ability to communicate complex subjects and she organised a series of Sunday lectures on science and religion throughout Britain. Aveling also helped Charles Bradlaugh in his struggle to be allowed to take his seat in the House of Commons after he was elected to represent Northampton in the 1880 General Election.

In 1881 Aveling met Charles Darwin and had several long meetings with him about science and religion. Aveling published the results of these discussions in a book The Religious Views of Charles Darwin. Controversially, Aveling claimed in his book that Darwin was a atheist.

Annie Besant introduced Aveling to H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). When Aveling was a candidate for the London School Board elections in November, 1882, members of both the Secular Society and the SDF campaigned for him. Aveling, whose main policy was the free, elementary schooling for the working class, was elected to the School Board.

Some members of the Secular Society and the Social Democratic Federation, disapproved of Aveling's moral behaviour. Aveling, who had married Isabel Frank in 1872, had a number of relationships with women, including Annie Besant and Eleanor Marx. In 1883 Aveling and Marx began to live together. Although Marx saw this as the same as if someone was officially married, Aveling continued to have affairs with other women.

Aveling became a member of the Social Democratic Federation but disagree d with H. H. Hyndman about a wide range of different issues. At a SDF meeting on 27th December, 1884, the executive voted by a majority of two (10-8), that it had no confidence in Hyndman. When Hyndman refused to resign, some members, including Aveling, William Morris, and Eleanor Marx left the party and formed a new organisation called the Socialist League. Aveling also worked closely with Morris to produce the Socialist League's journal, Commonweal.

As well as writing for the Commonweal Aveling helped translate Das Kapital into English and co-authored The Woman Question (1886) with Eleanor Marx. Aveling was an unpopular figure in the Socialist League and after one dispute in May 1886 he left the organisation. Later that year Aveling and Marx went on a tour of the United States organised by the Socialist Party of America. Although the couple drew large crowds, Aveling became involved in a conflict with party leaders over what they considered to be his extravagant claims for expenses.

When Edward Aveling returned to England he joined with Friedrich Engels to form a new Marxist working class party. However, by this time, Aveling was completely distrusted by socialists in Britain and received little support for the venture.

Disillusioned with politics, Aveling became a playwright. Four of his plays were performed but none of them were successful. Aveling also joined with Eleanor Marx to put on Henrik Ibsen's play, A Doll's House. The production was attacked by critics who claimed that it was "destructive of family life".

In 1895, Aveling became seriously ill with kidney disease and Eleanor spent many months nursing him back to health. After Aveling recovered he left Eleanor and moved in with Eva Frye, a 22 year old actress. However, after a few months, Aveling, who was deeply in debt, returned to Eleanor who had recently been left money by Friedrich Engels.

Aveling became ill again in 1898 and had to have major surgery. Eleanor Marx once again had the job of looking after him. Soon after he recovered, Aveling told Eleanor that he had secretly married Eva Frye and was returning to her. Unable to bear the pain of this latest betrayal, Eleanor committed suicide on 31st March, 1898. Edward Aveling, who was now completely ostracized by the labour movement, had a relapse and died on 2nd August, 1898.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Aveling and Eleanor Marx, The Woman Question (1886)

The truth, not fully recognized even by those anxious to do good to women, is that she, like the labour classes, is in an oppressed condition; that her position, like theirs, is one of merciless degradation. Women are the creatures of an organized tyranny of men, as the workers are the creatures of an organised tyranny of men, as the workers are the creatures of an organized tyranny of idlers.

Both the oppressed classes, women and the immediate producers, must understand that their emancipation will come from themselves. Women will find allies in the better sort of men, as the labourers are finding allies among the philosophers, artists, and poets. But the one has nothing to hope from man as a whole, and the other has nothing to hope from the middle class as a whole.

(2) Ben Tillett, Memories and Reflections (1931)

Another of our helpers at headquarters (during the London Docker's Strike) was Karl Marx's daughter, Eleanor, the tragic wife of Edward Aveling. Brilliant, devoted and beautiful, she was Marx's youngest daughter, and a Londoner by birth. At the time of our strike, she was only thirty years old. She lived with Aveling under very unhappy conditions, which did not break her spirit, or cause her to waver in her devotion to the working-class cause. She was active in support of the efforts we were making to organize unskilled labour in the East End of London. She was destined, poor girl, within a few years to put an end to her unhappiness by taking her own life.

Not many of us knew, at the time, about the wretchedness of her relations with Aveling. He was a man of exceptionally brilliant intellect, a scholar, and a scientist, who taught chemistry, physiology and comparative anatomy at University lecturer. He had an Irishman's charm, but he was wayward, unstable, with darker traits in his character which spelt misery and emotional strain for the woman associated with him.

(3) Henry Snell, Men Movements and Myself (1936)

Eleanor Marx was a woman of heavy build, very dark, widely read and widely travelled, and it was a privilege to talk with her about her distinguished father and his famous friends, Engels, Bebel, and others. Of her husband, Dr. Edward Aveling, little need be said. He was a man of great capacity, a magnificent speaker with a wonderful voice, but his sense of responsibility towards others, or to whatever cause he elected to serve, was quite undeveloped. It was through my acquaintance with Dr. Aveling that I first realised that a fine education and a powerful mind did not of necessity make a fine man.

(4) Sidney Hook, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987)

Because of my Guggenheim project, I made several efforts to arrange a meeting with Edouard Bernstein, the famous revisionist of Marx, then living in retirement. His figure and outlook, in the perspective of the fifty years after Marx's death, had grown enormously. I was put off several times, and when I finally met him, I realized why. He was suffering from advanced arteriosclerosis and was attended by a nurse. He seemed at first reluctant to talk about his reminiscences of Marx, but at the outset of our talk, to my chagrin, was eager to describe his first day at school, about which he had very vivid memories. I kept reverting to various episodes of Marx's life and to some of Marx's literary remains, which Engels had entrusted to Bernstein. His manner was benign and friendly. Only twice did he lose his composure and burst out with a stormy lucidity. The first time was when I mentioned Edward Aveling with whom Eleanor Marx, Marx's youngest daughter, had been enamored, and who had been the cause of her suicide. Bernstein rose from his chair with flushed face and agitated tone and voice and denounced him as an "arch scoundrel". I did not, however, get a very coherent account of Aveling's infamy. The second time was when I mentioned in passing that I had been invited to pursue my studies on the period from Hegel to Marx at the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow by its director, David Ryazanov. When he heard Ryazanov's name, he fumed and charged him with being a liar and a thief, who had stolen materials from the Social Democratic Party archives. Throughout the hour or so when I kept bringing up the name of Lenin in hopes of initiating some discussion of Lenin's Marxism, he made disparaging references to "the Bolsheviks," but my most significant memory of the conversation was his reference to himself, as if he suspected this American pilgrim of an excess of Marxist piety, as a "methodological reactionary." For him socialism was a child of the Enlightenment. "I am still an eighteenth-century rationalist," he said, "and not at all ashamed of it. I believe that in essentials their approach was both valid and fruitful." Was this the method or approach of Marx? I inquired. His answer was not altogether clear, but its drift was that it was a continuation with important historical differences. It was somewhere at this point, as I recall, that he lowered his voice and in a confidential whisper, as if afraid of being overheard, leaned toward me and observed: "The Bolsheviks are not altogether unjustified in claiming Marx as their own. Marx, you know, had a strong Bolshevik streak in him." The nurse who had been silently present all the time signaled me that the interview was over.