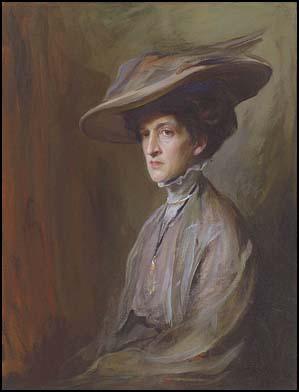

Margot Asquith

Margaret Emma Alice (Margot) Tennant, the sixth daughter and eleventh child of Sir Charles Tennant (1823–1906) and Emma Winsloe (1821–1895), was born at Innerleithen, Peeblesshire, on 2nd February 1864. Her father was a wealthy Scottish industrialist and Liberal MP. According to her biographer, Eleanor Brock: "Agile and energetic, she revelled in the freedom of her country childhood. She loved riding, and when introduced to hunting in 1880 she found an activity in which she could excel; she rode with the Cottesmore, the Quorn, and the Belvoir hunts. In one of her many accidents, however, her nose was broken, and her upper lip became misshapen.... She was educated mostly at home, and read widely in her father's library; she also attended a seminary in London run by Mlle de Mennecy, and spent five months in Dresden studying music and German."

Margot first met Herbert Henry Asquith, the Liberal MP for East Fife, in 1890. Asquith's wife, Helen, died suddenly in the following year from typhoid, leaving five children. Asquith, who was twelve years older than Margot, asked her to marry him. At first she rejected the idea but she changed her mind and they were married on 10th May 1894.

Margot wrote in her diary five days after her marriage to Asquith: "I realized that in some ways with all his tact and delicacy, all his intellect and bigness, all his attributes, he had a common place side to him which nothing could alter... It is not in his nature to feel the subtlety of love making, the dazzle and fun of it, the tiny almost untouchable fellowship of it... He has passion, devotion, self-mastery, but not the nameless something that charms and compels and receives and combats a woman's most fastidious advances."

Margot Asquith wrote to her stepson, Raymond Asquith about her new role as stepmother: "You must not think that I could imagine even a possibility of filling your mother's (and my friend's) place. I only ask you to let me be your companion - and if needs be your help-mate. There is room for everyone in life if they have the power to love. I shall count upon your help in making my way with Violet and your brothers... I should like you to let me gradually and without effort take my place among you, and if I cannot - as indeed I would not - take your mother's place among you, you must at least allow me to share with you her beautiful memory."

Over the next few years she had five children but only Elizabeth Asquith (1897–1945) and Anthony Asquith (1902–1968) survived, three dying at birth. Margot had a reputation for speaking her mind and relations with her step-children were difficult. This was especially true of her dealings with Raymond Asquith, the eldest, and Violet Bonham Carter, the only daughter.

Margot kept a diary for most of her life. After marrying Herbert Henry Asquith she began to record political events as well as family matters. In 1904 she wrote that she intended to write "with absolute fidelity and indiscretion the private and political events of the coming years".

The Liberals achieved power following the 1906 General Election. The new Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, gave Asquith the important post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Margot rejected the idea of living at 11 Downing Street, as she could see no possibility of fitting into it with "16 servants and 9 of the family". The family therefore continued to live at 20 Cavendish Square.

Asquith's strong opposition to women's suffrage made him extremely unpopular with the NUWSS. Suffragists were particularly angry that the man who was responsible for deciding how much tax they paid, should deny them political representation. Several times in 1906 members of the WSPU made attempts to disrupt meetings where he was speaking.

In April, 1908, Henry Campbell-Bannerman resigned and Asquith replaced him as Prime Minister. Working closely with David Lloyd George, his radical Chancellor of the Exchequer, Asquith introduced a whole series of reforms including the Old Age Pensions Act and the People's Budget that resulted to a conflict with the House of Lords.

Eleanor Brock has argued: "It is difficult to assess what influence, if any, was exerted by Margot, especially during the premiership. On the personal side she was highly demanding and critical, and poor health frequently made her difficult. She was capable of making terrible scenes (as she herself recounted). All this meant a far from restful home life for Asquith. On the other hand she was fiercely loyal to him, and seldom complained of her husband's close friendships with other women." Margot did try to influence government policies and after one conversation with Lloyd George, he complained about this to Asquith. Margot recorded in her diary: "Henry hated her missionary tendencies".

After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Herbert Henry Asquith made strenuous attempts to achieve political solidarity and in May 1915 formed a coalition government. Gradually the Conservatives in the cabinet began to question Asquith's abilities as a war leader. So also did Lord Northcliffe, the powerful newspaper baron, and his newspapers, The Daly Mail and The Times led the attack on Asquith. Margot responded to this criticism by suggesting that Asquith suspend the two newspapers.

On 15th September, 1916, Raymond Asquith led his men on a attack on the German trenches at Lesboeufs. He was hit in the chest by a bullet and died on the way to the dressing station. According to a soldier quoted by John Jolliffe: "there is not one of us who would not have changed places with him if we had thought that he would have lived, for he was one of the finest men who ever wore the King's uniform, and he did not know what fear was." Only five of the twenty-two officers in Asquith's battalion survived the battle unscathed."

His sister, Violet Bonham Carter, wrote: "He was shot through the chest and carried back to a shell-hole where there was an improvised dressing station. There they gave him morphia and he died an hour later. God bless him. How he has vindicated himself - before all those who thought him merely a scoffer - by the modest heroism with which he chose the simplest and most dangerous form of service - and having so much to keep for England gave it all to her with his life."

The consequences of the Battle of the Somme put further pressure on Asquith. Colin Matthew has commented: "The huge casualties of the Somme implied a further drain on manpower and further problems for an economy now struggling to meet the demands made of it... Shipping losses from the U-boats had begun to be significant... Early in November 1916 he called for all departments to write memoranda on how they saw the pattern of 1917, the prologue to a general reconsideration of the allies' position."

At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, David Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation.

On 2nd December Asquith agreed to the setting up of "a small War Committee to handle the day to day conduct of the war, with full powers", independent of the cabinet. This information was leaked to the press by Edward Carson. On 4th December The Times used these details of the War Committee to make a strong attack on Asquith. The following day he resigned from office. On 7th December George V asked Lloyd George to form a second coalition government.

Virginia Woolf dined with the Asquiths "two nights after their downfall; though Asquith himself was quite unmoved, Margot started to cry into the soup." His biographer, Colin Matthew, believes he was pleased that he was out of power: "He was not a great war leader, and he never attempted to portray himself as such. But he was not a bad one, either. Wartime to him was an aberration, not a fulfilment. In terms of the political style of Britain's conduct of the war, that was an important virtue, but it led Asquith to underestimate the extent to which twentieth-century warfare was an all-embracing experience, and his sometimes almost perverse personal reluctance to appear constantly busy and unceasingly active told against him in the political and press world generally."

One of Asquith's main critics in the House of Commons was Noel Pemberton Billing, the Independent MP for East Hertfordshire. Relying on information supplied by Harold S. Spencer, Billing published an article in The Imperialist on 26th January, 1918, revealing the existence of a Black Book: "There exists in the Cabinet Noir of a certain German Prince a book compiled by the Secret Service from reports of German agents who have infested this country for the past twenty years, agents so vile and spreading such debauchery and such lasciviousness as only German minds can conceive and only German bodies execute."

Billing claimed the book listed the names of 47,000 British sexual perverts, mostly in high places, being blackmailed by the German Secret Service. He added: "It is a most catholic miscellany. The names of Privy Councillors, youths of the chorus, wives of Cabinet Ministers, dancing girls, even Cabinet Ministers themselves, while diplomats, poets, bankers, editors, newspaper proprietors, members of His Majesty's Household follow each other with no order of precedence." Billing went onto argue that "the thought that 47,000 English men and women are held in enemy bondage through fear calls all clean spirits to mortal combat".

In February, 1918, it was announced by theatrical producer, Jack Grein, that Maud Allan would give two private performances of Oscar Wildes's Salomé in April. It had to be a private showing because the play had long been banned by the Lord Chamberlain as being blasphemous. Noel Pemberton Billing had heard rumours Allan was a lesbian and was having an affair with Margot Asquith. He also believed that Allan and the Asquiths were all members of the Unseen Hand.

On 16th February, 1918, the front page of The Vigilante had a headline, "The Cult of the Clitoris". This was followed by the paragraph: "To be a member of Maud Allan's private performances in Oscar Wilde's Salome one has to apply to a Miss Valetta, of 9 Duke Street, Adelphi, W.C. If Scotland Yard were to seize the list of those members I have no doubt they would secure the names of several of the first 47,000."

As soon as Allan became aware of the article she put the matter into the hands of her solicitor. In March 1918, Allan commenced criminal proceedings for obscene, criminal and defamatory libel. During this period Billing was approached by Charles Repington, the military correspondent of The Times. He was concerned about the decision by David Lloyd George to begin peace negotiations with the German foreign minister. According to James Hayward, the author of Myths and Legends of the First World War (2002): "Talk of peace outraged the Generals, who found allies in the British far right. Repington suggested that Billing get his trial postponed and use the mythical Black Book to smear senior politicians and inflame anti-alien feeling in the Commons. By this logic, the current peace talks would be ruined and Lloyd George's authority undermined."

The libel case opened at the Old Bailey in May, 1918. Billing chose to conduct his own defence, in order to provide the opportunity to make the case against the government and the so-called Unseen Hand group. The prosecution was led by Ellis Hume-Williams and Travers Humphreys and the case was heard in front of Chief Justice Charles Darling.

Billing's first witness was Eileen Villiers-Stuart. She explained that she had been shown the Black Book by two politicians since killed in action in the First World War. As Christopher Andrew has pointed out in Secret Service: The Making of the British Intelligence Community (1985): "Though evidence is not normally allowed in court about the contents of documents which cannot be produced, exceptions may be made in the case of documents withheld by foreign enemies. Mrs Villiers Stewart explained that the Black Book was just such an exception." During the cross-examination Villiers-Stewart claimed that the names of Margot Asquith, Herbert Asquith and Richard Haldane were in the Black Book. Judge Charles Darling now ordered her to leave the witness-box. She retaliated by saying that Darling's name was also in the book.

The next witness was Harold S. Spencer. He claimed that he had seen the Black Book while looking through the private papers of Prince William of Wied of Albania in 1914. Spencer claimed that Alice Keppel, the mistress of Edward VII, was a member of the Unseen Hand and has visited Holland as a go-between in supposed peace talks with Germany.

On 4th June, 1918, Billing was acquitted of all charges. As James Hayward has pointed out: "Hardly ever had a verdict been received in the Central Criminal Court with such unequivocal public approval. The crowd in the gallery sprang to their feet and cheered, as women waved their handkerchiefs and men their hats. On leaving the court in company with Eileen Villiers-Stewart and his wife, Billing received a second thunderous ovation from the crowd outside, where his path was strewn with flowers."

Cynthia Asquith wrote in her diary: "One can't imagine a more undignified paragraph in English history: at this juncture, that three-quarters of The Times should be taken up with such a farrago of nonsense! It is monstrous that these maniacs should be vindicated in the eyes of the public... Papa came in and announced that the monster maniac Billing had won his case. Damn him! It is such an awful triumph for the unreasonable, such a tonic to the microbe of suspicion which is spreading through the country, and such a stab in the back to people unprotected from such attacks owing to their best and not their worst points." Basil Thomson, who was head of Special Branch, an in a position to know that Eileen Villiers-Stuart and Harold S. Spencer had lied in court, wrote in his diary, "Every-one concerned appeared to have been either insane or to have behaved as if he were."

After the war Margot Asquith decided to write her Autobiography, based on her diary. As Eleanor Brock has pointed out: "The publication of the first volume in 1920 was preceded by extracts in English and American newspapers. Immediate offence was given to some of her friends by her unvarnished descriptions of them - Curzon was never reconciled to her. The excessive candour and the egotism of the author were severely commented on by critics, and surprise was expressed at her account, in the newspaper version, of a conversation with Lord Salisbury which was held apparently after his death." A second volume was published in 1922.

Other books by Margot Asquith included Places and Persons (1925), Lay Sermons (1927), More Memories (1933), Myself when Young (1938) and Off the Record (1943). Dorothy Parker did not appreciate Asquith's books and wrote in The New Yorker: "Margot Asquith's latest book, has all the depth and glitter of a worn dime." She added that "the affair between Margot Asquith and Margot Asquith will live as one of the prettiest love stories in all literature".

Margot Asquith died at 14 Kensington Square on 28th July 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Jane Ridley, The Spectator (28th September, 2002)

The publicity material likens this book to The Forsyte Saga, but in fact it's far more gripping than fiction: the true story of a larger-than-life political dynasty. The diaries of Margot Asquith form the core of the book. For too long Margot's voluminous diaries have been unavailable, and Colin Clifford is the first biographer to gain unrestricted access. He has put them to excellent use.

Daughter of the fabulously rich Sir Charles Tennant ("the Bart"), Margot took London by storm with her energy and outrageous wit. Her diaries reveal a less attractive side. She emerges as self-obsessed, with an irritating habit of detailing pert exchanges with the great and the good in which she always comes out best. She was also a crashing snob (which was somewhat rich, coming from the granddaughter of a Glasgow handloom weaver). Hysterically opposed to women's suffrage, she attacked the suffragettes as "wombless, vicious, cruel women"....

When Margot Tennant burst into his life, Herbert Asquith was a barrister and Liberal MP leading a Pooterish domestic existence in Hampstead, where he lived with his young family. On holiday in Scotland his wife Helen Melland suddenly died of typhoid. Only a few weeks later, Asquith was writing love letters to Margot.

After consulting her men friends, Margot decided to drop her fox-hunting boyfriends and marry Henry, as she called Asquith (she disliked the name Herbert). She was not at all in love with him - Colin Clifford gives Margot's hilarious account of their wedding night when, after her bedtime milk and biscuits, she lay stiffly in Henry's arms and nothing happened. Soon she was regretting the whole thing and dismissing Asquith as "commonplace". Her five stepchildren were a trial, especially Violet, the only daughter, to whom she took an instant dislike: "a hard, commonplace, clever little girl with a frightful voice".

But Margot had picked the right man. Asquith rose effortlessly up the Liberal ladder, and Margot became almost pathetically dependent on him. She had two children, but wrecked her health with a series of ghastly childbirths (why, one wonders, did she have such trouble?). She became hysterical, lost weight, couldn't sleep, lost her power of speech (that must have been a relief). She was a political liability, constantly trying to meddle behind Henry's back and eaten up with jealousy of clever Violet, who eclipsed her as the centre of Henry's attention. "How dare you become Prime Minister when I'm away," Violet wired her father in 1908.

The Asquith children turned out to be the most brilliant of their generation. ("The whole Asquith family overvalue brains," complained Margot. "I'm a little tired of brains: they are apt to go to the head.") Yet, as Colin Clifford suggests, the children were subtly affected by the death of their mother Helen. The most complex of the Asquiths was Raymond, who was academically a star performer like his father, but strangely tortured and unfulfilled. The leader of the "lost generation", he was killed at the Somme in 1916. Colin Clifford states in his acknowledgments that Raymond's family felt unable to agree with much of what is written in this book, but Raymond's subversive black sarcasm and refusal to act the part of officer and gentleman make him if anything more interesting.

Clifford valiantly defends Asquith against his critics. He denies, for example, that Asquith drank too much - though who can blame poor Squiff if he did become over-fond of champagne with a wife like Margot? But Asquith's indifference to his sons is chilling. He didn't write to Raymond once during the war - and this at a time when he was writing three or four times a day to 28-year-old Venetia Stanley, with whom he was obsessed.

Asquith was a notorious groper, but his affair with Venetia Stanley was almost too much for Margot, who became more bonkers than ever. She was criticised for doing no "war work" as the prime minister's wife, and one can't help feeling the critics had a point. If only she had poured her formidable energies into something more worthwhile than wallowing in self-pity - and what a fool she was to write it all down.

(2) Colin Clifford, The Asquiths (2002)

By the time Margot heard the clock strike eleven she felt worn out and "at a certain risk of being thought bold" said she was going to bed. As she undressed and put on the smart night gown she had bought specially for the occasion, she thought how much she would have preferred it if it was Peter or Evan rather than her new husband who would come through the bedroom door. She said her prayers, got into bed and drank the glass of milk and munched the biscuits her maid always left her, while reading the day's biblical selection in Daily Light as she prepared for the coming ordeal. There was a knock at the door and Asquith came in swathed in an Indian dressing gown, grinning as he caught sight of his new wife sipping her milk. He knelt down and clasping Margot's hand to his forehead, said his prayers. He then walked round to the other side of the bed, but she refused to let him put out the candle. Trying to adopt a mock playful tone, she asked "Do you propose to come into my bed?"

"Yes," was the abrupt response. She wished he had responded with a tone of mock formality "with your permission", but cursed herself for always finding fault as he got into bed and put his arms around her. "I lay very tired with my head on his shoulder and felt him shudder under my most restrained embrace. We lay quite still and silent and I felt very low and tired and then I said I think we will go to sleep." She put out the candle. "Then he kissed my hands and my hair very sweetly and we retired to the opposite sides of the bed." All she felt was "immense drowsiness mixed with gratitude to him for his fine control and understanding". Margot was awoken the following morning by the birds singing and slipped into Asquith's arms and "lay in a close and very tender embrace for some time - my face pressed between his hair and the pillow and with great peace". Gee called at nine-thirty and her new husband went to dress as the maid poured the bath.

(3) Margot Asquith, diary entry on Herbert Henry Asquith (15th May, 1894)

I realized that in some ways with all his tact and delicacy, all his intellect and bigness, all his attributes, he had a common place side to him which nothing could alter... It is not in his nature to feel the subtlety of love making, the dazzle and fun of it, the tiny almost untouchable fellowship of it... He has passion, devotion, self-mastery, but not the nameless something that charms and compels and receives and combats a woman's most fastidious advances.

(4) Margot Asquith, Autobiography (1920)

On Sunday, September the 17th, we were entertaining a weekend party, which included General and Florry Bridges, Lady Tree, Nan Tennant, Bogie Harris, Arnold Ward, and Sir John Cowans. While we were playing tennis in the afternoon my husband went for a drive with my cousin, Nan Tennant. He looked well, and had been delighted with his visit to the front and all he saw of the improvement in our organization there: the tanks and the troops as well as the guns. Our Offensive for the time being was going amazingly well. The French were fighting magnificently, the House of Commons was shut, the Cabinet more united, and from what we heard on good authority the Germans more discouraged. Henry told us about Raymond, whom he had seen as recently as the 6th at Fricourt.

As it was my little son's last Sunday before going back to Winchester I told him he might run across from the Barn in his pyjamas after dinner and sit with us while the men were in the dining-room.

While we were playing games Clouder, our servant - of whom Elizabeth said, "He makes perfect ladies of us all" - came in to say that I was wanted.

I left the room, and the moment I took up the telephone I said to myself, "Raymond is killed".

With the receiver in my hand, I asked what it was, and if the news was bad.

Our secretary, Davies, answered, "Terrible, terrible news. Raymond was shot dead on the 15th. Haig writes full of sympathy, but no details. The Guards were in and he was shot leading his men the moment he had gone over the parapet."

I put back the receiver and sat down. I heard Elizabeth's delicious laugh, and a hum of talk and smell of cigars came down the passage from the dining-room.

I went back into the sitting-room.

"Raymond is dead," I said, "he was shot leading his men over the top on Friday."

Puffin got up from his game and hanging his head took my hand; Elizabeth burst into tears, for though she had not seen Raymond since her return from Munich she was devoted to him. Maud Tree and Florry Bridges suggested I should put off telling Henry the terrible news as he was happy.

I walked away with the two children and rang the bell:

"Tell the Prime Minister to come and speak to me", I said to the servant.

Leaving the children, I paused at the end of the dining-room passage; Henry opened the door and we stood facing each other.

He saw my thin, wet face, and while he put his arm round me I said: "Terrible, terrible news."

At this he stopped me and said: "I know... I've known it.... Raymond is dead."

He put his hands over his face and we walked into an empty room and sat down in silence.