Hiroshima

In 1942 the Manhattan Engineer Project was set up in the United States under the command of Brigadier General Leslie Groves. Allied scientists recruited to produce an atom bomb included Robert Oppenheimer, David Bohm, Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner, Otto Frisch, Rudolf Peierls, Felix Bloch, Niels Bohr, Emilio Segre, James Franck, Enrico Fermi, Klaus Fuchs and Edward Teller.

Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were deeply concerned about the possibility that Germany would produce the atom bomb before the allies. At a conference held in Quebec in August, 1943, it was decided to try and disrupt the German nuclear programme. In February 1943, SOE saboteurs successfully planted a bomb in the Rjukan nitrates factory in Norway. As soon as it was rebuilt it was destroyed by 150 US bombers in November, 1943. Two months later the Norwegian resistance managed to sink a German boat carrying vital supplies for its nuclear programme.

Meanwhile the scientists working on the Manhattan Project were developing atom bombs using uranium and plutonium. The first three completed bombs were successfully tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16th July, 1945. James Chadwick later described what he saw during the test: "An intense pinpoint of light which grew rapidly to a great ball. Looking sideways, I could see that the hills and desert around us were bathed in radiance, as if the sun had been turned on by a switch. The light began to diminish but, peeping round my dark glass, the ball of fire was still blindingly bright ... The ball had then turned through orange to red and was surrounded by a purple luminosity. It was connected to the ground by a short grey stem, resembling a mushroom."

By the time the atom bomb was ready to be used Germany had surrendered. James Franck and Leo Szilard drafted a petition signed by just under 70 scientists opposed to the use of the bomb on moral grounds. Franck pointed out in his letter to Truman: "The military advantages and the saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and by a wave of horror and repulsion sweeping over the rest of the world and perhaps even dividing public opinion at home. From this point of view, a demonstration of the new weapon might best be made, before the yes of representatives of all the United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America could say to the world, "You see what sort of a weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future if other nations join us-in this renunciation and agree to the establishment of an efficient international control."

However, the advice of the scientists was ignored by Harry S. Truman, the USA's new president, and he decided to use the bomb on Japan. General Dwight Eisenhower agreed with the scientists: "I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of face."

At Yalta, the Allies had attempted to persuade Joseph Stalin to join in the war with Japan. By the time the Potsdam meeting took place, they were having doubts about this strategy. Winston Churchill in particular, were afraid that Soviet involvement would lead to an increase in their influence over countries in the Far East. On 17th July 1945 Stalin announced that he intended to enter the war against Japan.

President Harry S. Truman now insisted that the bomb should be used before the Red Army joined the war against Japan. Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, wanted the target to be Kyoto because as it had been untouched during previous attacks, the dropping of the atom bomb on it would show the destructive power of the new weapon. However, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, argued strongly against this as Kyoto was Japan's ancient capital, a city of immense religious, historical and cultural significance. General Henry Arnold supported Stimson and Truman eventually backed down on this issue.

President Truman wrote in his journal on 25th July, 1945: "This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Secretary of War, Mr Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we, as leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new. He & I are in accord. The target will be a purely military."

Truman's military advisers accepted that Kyoto would not be targeted but insisted that another built-up area should be chosen instead: "While the bombs should not concentrate on civilian areas, they should seek to make a profound a psychological impression as possible. The most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers' houses."

Winston Churchill insisted that two British representives should witness the dropping of the atom bomb. Squadron Leader Leonard Cheshire and William Penny, a scientist working on the Manhattan Project, were chosen for this task. Churchill ordered them to learn "about the taqctical aspects of using such a weapon, reach a conclusion about its future implications for air warfare and report back to the Prime Minister."

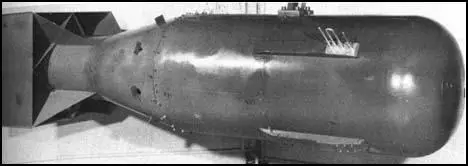

General Thomas Farrell, Commander of the Manhattan Project, explained to Cheshire and Penny that they had produced two types of bomb. Fat Man relied upon implosion: a 12 lb sphere of plutonium would be abruptly squeezed to super-critically by the detonation of an envelope of explosive. Little Boy functioned by a gun mechanism which fired two subcritical masses of uranium 235 together.

President Harry S. Truman eventually decided that the bomb should be dropped on Hiroshima. It was the largest city in the Japanese homeland (except Kyoto) which remained undamaged, and a place of military industry. However, Truman, after listening from advice of General Curtis LeMay, refused permission for Leonard Cheshire and William Penny to witness the event. Leslie Groves, according to Cheshire, "said firmly that there was no room for either of us; in any case he couldn't see why we needed to be there, for we would receive a full written report and could ask to see any documentation we wanted."

On 6th August 1945, a B29 bomber piloted by Paul Tibbets, dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. Michihiko Hachiya was living in the city at the time: "Hundreds of people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags or a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they stopped. I found them lying so thick on both sides of the road that it was impossible to pass without stepping on them."

Later that day President Harry S. Truman made a speech where he argued: "The harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been used against those who brought war to the Far East. We have spent $2,000,000,000 (about $500,000,000) on the greatest gamble in history, and we have won. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development."

Truman then issued a warning to the Japanese government: "We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake, we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued from Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of run from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with a fighting skill of which they have already become well aware."

The journalist, John Hersey, reported that the dropping of the atom bomb was having long term consequences: "Dr. Sasaki and his colleagues at the Red Cross Hospital watched the unprecedented disease unfold and at last evolved a theory about its nature. It had, they decided, three stages. The first stage had been all over before the doctors even knew they were dealing with a new sickness; it was the direct reaction to the bombardment of the body, at the moment when the bomb went off, by neutrons, beta particles, and gamma rays. The apparently uninjured people who had died so mysteriously in the first few hours or days had succumbed in this first stage. It killed ninety-five per cent of the people within a half-mile of the center, and many thousands who were farther away. The doctors realized in retrospect that even though most of these dead had also suffered from burns and blast effects, they had absorbed enough radiation to kill them. The rays simply destroyed body cells - caused their nuclei to degenerate and broke their walls. Many people who did not die right away came down with nausea, headache, diarrhea, malaise, and fever, which lasted several days. Doctors could not be certain whether some of these symptoms were the result of radiation or nervous shock. The second stage set in ten or fifteen days after the bombing. Its first symptom was falling hair. Diarrhea and fever, which in some cases went as high as 106, came next. Twenty-five to thirty days after the explosion, blood disorders appeared: gums bled, the white-blood-cell count dropped sharply, and petechiae (eruptions) appeared on the skin and mucous membranes. The drop in the number of white blood corpuscles reduced the patient's capacity to resist infection, so open wounds were unusually slow in healing and many of the sick developed sore throats and mouths. The two key symptoms, on which the doctors came to base their prognosis, were fever and the lowered white-corpuscle count. If fever remained steady and high, the patient's chances for survival were poor."

One survivor described the death of her daughter from radiation sickness. "She had no burns and only minor external wounds. She was quite all right for a while. But on the 4th September, she suddenly became sick. She had spots all over her body. Her hair began to fall out. She vomited small clumps of blood many times. I felt this was a very strange and horrible disease. We were all afraid of it, and even the doctor didn't know what it was. After ten days of agony and torture, she died on September 14th." It has been estimated that over the years around 200,000 people have died as a result of this bomb being dropped.

Japan did not surrender immediately and a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later. On 15th August the Japanese surrendered. The Second World War was over.

Primary Sources

(1) General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, told President Harry S. Truman that he was opposed to the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan.

I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of "face".

(2) Robert Oppenheimer in conversation with Paul Tibbets (1945)

Your biggest problem may be after the bomb has left your aircraft. The shock waves from the detonation could crush your plane. I am afraid that I can give you no guarantee that you will survive.

(3) Deke Parsons, one of the team working on the Manhattan Project, gave a talk to Paul Tibbets and his team on 4th August, 1945.

The bomb you are going to drop is something new in the history of warfare. It is the most destructive weapon ever produced. We think it will knock out almost everything within a three-mile radius. No one knows exactly what will happen when the bomb is dropped from the air. Even if it exploded at the planned altitude of 1850 feet it might crack the earth's crust. The explosion's flash of light would be much brighter than the sun and could cause blindness.

(4) Colonel Paul Tibbets, was the commander of the plane that dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima.

We despatched an aircraft to check the weather. There was an alert in Hiroshima when the aircraft arrived. Then it turned away and the "All Clear" signal was given in the town. And then we arrived. I have never regretted it or been ashamed; I thought at the time I was doing my patriotic duty in carrying out the orders given to me.

(5) Robert Oppenheimer, on watching the first atomic bomb test (16th July, 1945)

I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

(6) John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946)

On August 7th, the Japanese radio broadcast for the first time a succinct announcement that very few, if any, of the people most concerned with its content, the survivors in Hiroshima, happened to hear: "Hiroshima suffered considerable damage as the result of an attack by a few B-29s. It is believed that a new type of bomb was used. The details are being investigated." Nor is it probable that any of the survivors happened to be tuned in on a short-wave rebroadcast of an extraordinary announcement by the president of the United States, which identified the new bomb as atomic: "That bomb had more power than twenty thousand tons of TNT. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British Grand Slam, which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare." Those victims who were able to worry at all about what had happened thought of it and discussed it in more primitive, childish terms – gasoline sprinkled from an airplane, maybe, or some combustible gas, or a big cluster of incendiaries, or the work of parachutists; but, even if they had known the truth, most of them were too busy or too weary or too badly hurt to care that they were the objects of the first great experiment in the use of atomic power, which (as the voices on the short wave shouted) no country except the United States, with its industrial know-how, its willingness to throw two billion gold dollars into an important wartime gamble, could possibly have developed.

(7) Michihiko Hachiya lived in Hiroshima during the Second World War. He wrote an account of the dropping of the atom bomb in his diary on 6th August, 1945.

Hundreds of people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags or a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they stopped. I found them lying so thick on both sides of the road that it was impossible to pass without stepping on them.

(8) One Hiroshima survivor described the death of her daughter from radiation sickness.

She had no burns and only minor external wounds. She was quite all right for a while. But on the 4th September, she suddenly became sick. She had spots all over her body. Her hair began to fall out. She vomited small clumps of blood many times. I felt this was a very strange and horrible disease. We were all afraid of it, and even the doctor didn't know what it was. After ten days of agony and torture, she died on September 14th.

(9) President Harry S. Truman, speech (6th August, 1945)

The harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been used against those who brought war to the Far East. We have spent $2,000,000,000 (about $500,000,000) on the greatest gamble in history, and we have won.

With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development.

Before 1939 it was the accepted belief of scientists that it was theoretically possible to release atomic energy, but none knew any practical method of doing it. By 1942 however, we knew the Germans were working feverishly to find a way to add atomic energy to other engines of war with which they hoped to enslave the world, but they failed. We may be grateful to Providence that the Germans got VI's and V2's and in limited quantities, and even more grateful that they did not get the atomic bomb at all.

The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us as well as the battles of the air, land and sea and we have now won the battle of the laboratories as we have won other battles. Before Pearl Harbour, scientific knowledge useful in war was pooled between the United States and Britain and many priceless.helps to our victories have come from the arrangement. Under that general policy, research on the atomic bomb was begun. With American and British scientists working together, we entered the race of discovery against the Germans.

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake, we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued from Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of run from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with a fighting skill of which they have already become well aware.

Although workers at the sites have been making the materials to be used in producing the greatest destructive force in history, they have not themselves been in danger beyond that of many other occupations for the utmost care has been take for their safety. The fact that we can release atomic energy ushers in a new era on man's understanding of nature's forces. I shall recommend the Congress of the United States to consider promptly establishment of an appropriate Commission to control the production and use of atomic power within the United States. I shall give further consideration and make a further recommendation to Congress as to how atomic power can become a powerful and forceful influence towards the maintenance of world peace.

(10) John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946)

Dr. Sasaki and his colleagues at the Red Cross Hospital watched the unprecedented disease unfold and at last evolved a theory about its nature. It had, they decided, three stages. The first stage had been all over before the doctors even knew they were dealing with a new sickness; it was the direct reaction to the bombardment of the body, at the moment when the bomb went off, by neutrons, beta particles, and gamma rays. The apparently uninjured people who had died so mysteriously in the first few hours or days had succumbed in this first stage. It killed ninety-five per cent of the people within a half-mile of the center, and many thousands who were farther away. The doctors realized in retrospect that even though most of these dead had also suffered from burns and blast effects, they had absorbed enough radiation to kill them. The rays simply destroyed body cells - caused their nuclei to degenerate and broke their walls. Many people who did not die right away came down with nausea, headache, diarrhea, malaise, and fever, which lasted several days. Doctors could not be certain whether some of these symptoms were the result of radiation or nervous shock. The second stage set in ten or fifteen days after the bombing. Its first symptom was falling hair. Diarrhea and fever, which in some cases went as high as 106, came next. Twenty-five to thirty days after the explosion, blood disorders appeared: gums bled, the white-blood-cell count dropped sharply, and petechiae [eruptions] appeared on the skin and mucous membranes. The drop in the number of white blood corpuscles reduced the patient's capacity to resist infection, so open wounds were unusually slow in healing and many of the sick developed sore throats and mouths. The two key symptoms, on which the doctors came to base their prognosis, were fever and the lowered white-corpuscle count. If fever remained steady and high, the patient's chances for survival were poor. The white count almost always dropped below four thousand; a patient whose count fell below one thousand had little hope of living. Toward the end of the second stage, if the patient survived, anemia, or a drop in the red blood count, also set in. The third stage was the reaction that came when the body struggled to compensate for its ills–when, for instance, the white count not only returned to normal but increased to much higher than normal levels. In this stage, many patients died of complications, such as infections in the chest cavity. Most burns healed with deep layers of pink, rubbery scar tissue, known as keloid tumors. The duration of the disease varied, depending on the patient's constitution and the amount of radiation he had received. Some victims recovered in a week; with others the disease dragged on for months.

As the symptoms revealed themselves, it became clear that many of them resembled the effects of overdoses of X-ray, and the doctors based their therapy on that likeness. They gave victims liver extract, blood transfusions, and vitamins, especially Bl. The shortage of supplies and instruments hampered them. Allied doctors who came in after the surrender found plasma and penicillin very effective. Since the blood disorders were, in the long run, the predominant factor in the disease, some of the Japanese doctors evolved a theory as to the seat of the delayed sickness. They thought that perhaps gamma rays, entering the body at the time of the explosion, made the phosphorus in the victims' bones radioactive, and that they in turn emitted beta particles, which, though they could not penetrate far through flesh, could enter the bone marrow, where blood is manufactured, and gradually tear it down. Whatever its source, the disease had some baffling quirks. Not all the patients exhibited all the main symptoms. People who suffered flash burns were protected, to a considerable extent, from radiation sickness. Those who had lain quietly for days or even hours after the bombing were much less liable to get sick than those who had been active. Gray hair seldom fell out. And, as if nature were protecting man against his own ingenuity, the reproductive processes were affected for a time; men became sterile, women had miscarriages, menstruation stopped.

(11) Studs Terkel interviewed Ted Allenby about his experiences fighting the Japanese Army during the Second World War for his book, The Good War (1985)

I was in Hiroshima and I stood at ground zero. I saw deformities that I'd never seen before. I know there are genetic effects that may affect generations of survivors and their children. I'm aware of all this. But I also know that had we landed in Japan, we would have faced greater carnage than Normandy. It would probably have been the most bloody invasion in history. Every Japanese man, woman, and child was ready to defend that land. The only way we took Iwo Jima was because we outnumbered them three to one. Still, they held us at bay as long as they did. We'd had to starve them out, month after month after month. As it was, they were really down to eating grass and bark off trees. So I feel split about Hiroshima. The damn thing probably saved my life.

(12) Joyce Storey, Joyce's War (1992)

That same year that Patty started school, the war ended. It had lasted for six long weary years, and for those of us who had been young at that time, it was a big slice out of our lives. When it was finally all over, there was singing and dancing in the streets. Victory bells rang and people cried and laughed at the same time and hugged each other. We had street parties for the children, and although they were too young to know what it was all about, they caught the excitement of the moment, and with balloons and streamers they joined in the fun. I made sponges and jellies along with Jean Brodie from down the road, and even helped with the paper hats.

News filtered through that the war had ended suddenly because a small bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. Nobody questioned why it had come to an abrupt halt. Like thousands of others, we were relieved and happy that hostilities had ceased and hoped that our lives could proceed along normal lines once more. It was several months before the word atomic was mentioned, and we were ignorant of its consequences. We ignored it all. The war was over and that was enough. Much later, we saw and heard the full horror of this weapon that the Americans had used and were appalled. That it must never happen again was a phrase that Governments bandied about for years, and which we believed, like so many other things. We were young and we were gullible. Impossible to think, then, that nuclear weapons would become the ultimate 'deterrent'. Impossible also to believe that when the final page of history was being written, we discovered that Germany had also been busy perfecting this deadly weapon of destruction, and it could have been us and not Hiroshima as the target. A moment for reflection. One sobering thought. How could things ever be the same again?