Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading

Rufus Isaacs, the second son and fourth of the nine children of Joseph Isaacs and his wife, Sarah Davis Isaacs, was born in London on 10th October 1860. His father was a successful fruit importer who was based in Spitalfields.

According to his biographer, Antony Lentin: "Rufus was sent away to school from an early age: to a kindergarten at Gravesend; between the ages of five and seven to a school in Brussels to learn French; then for some years as a boarder at an Anglo-Jewish school in Regent's Park. At all these schools he was precociously bright and exceedingly disruptive. In 1873 he entered University College School in Gower Street, London, where the headmaster noted his promise; but his father, seeing no future for him in higher education, removed him after less than a year in order to prepare him for the family business. Rufus was thirteen years old." (1)

Isaacs was sent to Europe to learn languages and the fruit import business. In 1879 he finally abandoned the family business to work in the foreign market at the stock exchange. At first he was successful but after an economic downturn and by 1884 he was £8,000 in debt. His father agreed to send him to study law at the Middle Temple. Isaacs was called to the bar on 17th November 1887, and three weeks later married Alice Cohen at the West London Synagogue. According to a friend "the Isaacs were a remarkably good-looking couple". (2)

Isaacs set up his own chambers and was a great success and after fifteen years he had an annual income of £30,000. He practised chiefly in the commercial court or before special juries, occasionally in the divorce court or the Old Bailey. Isaacs was able to do with little sleep, and often got up at 4 a.m. to prepare for the day's work, arriving "fresh and smiling" at his chambers. (3)

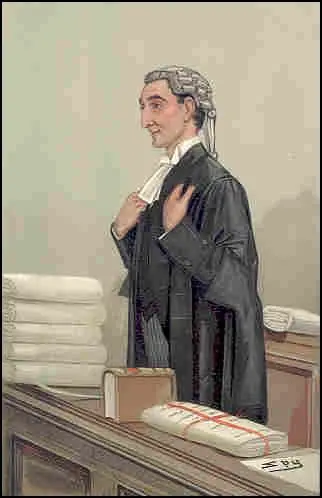

Successful Lawyer

Isaacs was an active member of the Liberal Party and as a lawyer he represented the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants when it was sued by the Taff Vale Railway Company in 1901 for losses during a strike. As a result of the case the union was fined £23,000. Up until this time it was assumed that unions could not be sued for acts carried out by their members. This court ruling exposed trade unions to being sued every time it was involved in an industrial dispute. (4)

Rufus Isaacs was elected to represent Reading at a by-election in August, 1904. He continued with his legal career and had several successes, including his defence of The Star newspaper in a libel action involving Joseph Chamberlain, the prosecution of the fraudulent company promoter Whitaker Wright, who committed suicide by swallowing cyanide in a court anteroom immediately after being convicted, and the defence of Sir Edward Russell on a charge of criminal libel and of Robert Sievier, a racehorse trainer, on a blackmail charge.

Isaacs developed a good reputation for cross-examination. "He was an engaging advocate: a slim, taut figure, with striking, chiselled features, and a melodious, beautifully modulated voice, delicate hands, firmly planted in the lapels of his coat, and an alert, compelling glance. His forensic strengths were his mastery of facts and figures, aided by a prodigiously retentive memory; great clarity of thought and expression; and total self-control... Always calm, always courteous, he never overstated his case, readily conceded his opponent's strong points, and knew how to put unpromising facts in the most favourable light." (5)

His speeches in court, where he used almost conversational language, were very effective with both judge and jury. John C. Davidson, a Conservative Party politician, commented: "I was immensely struck by his capacity of exacting information without the giver of the information really realising it. He always asked questions with an anesthetic in them, so that you really felt that if he was operating on you, you would never feel any pain." (6)

Marconi Scandal

In March 1910, H. H. Asquith appointed Isaacs as Solicitor-General and was knighted. His brother, Godfrey Isaacs, was a successful businessman and in August 1910, he became the managing director of the English Marconi Company. Godfrey was also on the board of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, that controlled the company operating in London. Isaacs had been given responsibility for selling 50,000 shares in the company to English investors before they became available to the general public. He advised Rufus Isaacs, to buy 10,000 of these shares at £2 apiece. He shared this information with David Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, the Chief Whip, and they both purchased 1,000 shares at the same price. On 18th April 1912 Murray also bought 2,000 shares for the Liberal Party. (7)

These shares were not available on the British stock market. On 19th April, the first day that shares in the Marconi Company of America were available in London, the shares opened at £3 and ended the day at £4. The main reason for this was the news that Herbert Samuel was in negotiations with the English Marconi Company to provide a wireless-telegraphy system for the British Empire. Rufus Isaacs now sold all his shares for a profit of £20,000. Whereas his fellow government ministers, Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, sold half their shares and therefore got the other half for free. Lloyd George then used this money to buy another 1,500 shares in the company. (8)

Cecil Chesterton, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc were involved with a new journal called The Eye-Witness. It was later pointed out that "the object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption". The editor wrote to his mother, Lloyd George has been dealing on the Stock Exchange heavily to his advantage with private political information". They immediately began to investigate the case. (9)

On 19th July, 1912, Herbert Samuel, the Postmaster-General, announced that a contract had been agreed with the English Marconi Company. A couple of days later, W. R. Lawson, wrote in the weekly Outlook Magazine: "The Marconi Company has from its birth been a child of darkness... Its relations with certain Ministers have not always been purely official or political." This became the beginning of what became known as the Marconi Scandal. (10)

Whereas the rest of the mainstream media ignored the story, over the next few weeks The Eye-Witness produced a series of articles on the subject. It suggested that Rufus Isaacs had made £160,000 out of the deal. It was also claimed that David Lloyd George, Godfrey Isaacs, Alexander Murray and Herbert Samuel had profited by buying shares based on knowledge of the government contract. (11)

The defenders of Lloyd George, Isaacs, Murray and Samuel, accused the magazine of anti-semitism, pointing out that three of the men named were Jewish. "They were all victims of the disease of the heart known as anti-semitism. It was a gift to them that the Attorney-General and his brother had the name of Isaacs, and the added bonus that the Postmaster General, who had negotiated the contract, was called Samuel." (12)

H. H. Asquith called a meeting with the accused men and discussed the possibility of legal action against the magazine. It was Asquith who eventually advised against this: "I suspect that Eyewitness has a very meagre circulation. I notice only one page of advertisements and then by Belloc's publishers. Prosecution would secure it notoriety which might yield subscribers." (13)

A debate on the Marconi contract took place on 11th October, 1912. Herbert Samuel explained that Marconi was the company best qualified to do the job and several Conservative MPs made speeches where they agreed with the government over this issue. The only dissenting voice was George Lansbury, the Labour MP, who argued that there had been "scandalous gambling in Marconi shares." (14)

Albert Spicer Parliamentary Committee

David Lloyd George responded by attacking those who had spread untrue stories about his share dealings: "The Honourable Member (George Lansbury) said something about the Government and he has talked about rumours. If the Honourable Member has any charge to make against the Government as a whole or against individual Members of it, I think it ought to be stated openly. The reason why the government wanted a frank discussion before going to Committee was because we wanted to bring here these rumours, these sinister rumours that have been passed from one foul lip to another behind the backs of the House." (15)

Later that day, Rufus Isaacs issued a statement about his share-dealings. "Never from the beginning... have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter". (16)

Leopold Maxse, the editor of The National Review, pointed out that Isaacs had been careful in his use of words. He speculated why he said that he had not purchased shares in "that company" rather than the "Marconi company". Maxse pointed out: "One might have conceived that (the Ministers) might have appeared at the first sitting clamouring to state in the most categorical and emphatic manner that neither directly nor indirectly, in their names or other people's names, have they had any transactions whatsoever... In any Marconi company throughout thc negotiations with the Government". (17)

Asquith announced that he would set-up a committee to look into the possibility of insider dealings. The committee had six Liberals (including the chairman, Albert Spicer), two Irish Nationalists and one Labour MP, which provided a majority over six Conservatives. The committee took evidence from witnesses for the next six months and caused the Government a great deal of embarrassment. (18)

On 14th February, 1913, the French newspaper, Le Matin, reported that Herbert Samuel, David Lloyd George and Rufus Isaacs, had purchased Marconi shares at £2 and sold them when they reached the value of £8. When it was pointed out that this was not true, the newspaper published a retraction and an apology. However, on the advice of Winston Churchill, they decided to take legal action against the newspaper.

Churchill argued that this would provide an opportunity to shape the consciousness of the general public. He suggested that the men should employ two barristers, Frederick Smith and Edward Carson, who were members of the Conservative Party: "The public was bound to notice that the integrity of two Liberal ministers was being defended by normally partisan members of the Conservative Party, and their appearance on behalf of Isaacs and Samuel would make it impossible for them to attack either man in the House of Commons debate which would surely follow." (19)

Churchill also had a meeting with Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times and The Daily Mail and persuaded him to treat the accused men "gently" in his newspapers. (20) However, other newspapers were less kind and gave a great deal of coverage to the critics of the government. For example, The Spectator, reported a speech made by Robert Cecil, where he argued: "It was his duty to express his honest and impartial opinion on the conduct of Mr. Lloyd George in the Marconi transaction. He had never said or suggested that the transaction was corrupt; but he did say that, if it was to be approved and recognized as the common practice among Government officials, then one of our greatest safeguards against corruption was absolutely destroyed. The transaction was bad and grossly improper, and it was made far worse by the fact that Mr. Lloyd George went about posing as an injured innocent. For a man in his position to defend that transaction was even worse than entering into it." (21)

During the House of Commons investigation the three accused Liberal MPs admitted they had purchased shares in the Marconi Company of America. However, as David Lloyd George pointed out, he had held no shares in any company which did business with the government and that he had never made improper use of official information. He ridiculed the charges which were made against him - some of which he invented, for example, the claim that he had made a profit of £60,000 on a speculative investment or that owned a villa in France. (22)

Alexander Murray was unable to appear before the Marconi Enquiry because he had resigned from the government and was working in Bogotá in Columbia. However, during the investigation, Murray's stockbroker was declared bankrupt and, in consequence, his account books and business papers were open to public examination. They revealed that Murray had not only purchased 2,500 shares in the American Marconi Company, but had invested £9,000 in the company on behalf of the Liberal Party. (23)

H. H. Asquith and Percy Illingworth, the new Chief Whip, denied knowledge of these shares. According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, Asquith and Illingworth had known about this "for some time". (24) John Grigg, the author of Lloyd George, From Peace To War 1912-1916 (1985), has argued that Asquith was also aware of these shares and this explains why he was so keen to cover-up the story. "If he had shown any sign of abandoning them, they might have contemplating abandoning him, and vice versa... there was probably a mutual recognition of the need for solidarity in a situation where the abandonment of one might well have led to the ruin of all." (25)

Rufus Isaacs was deeply hurt by this accusation of corruption. He admitted that "it was a mistake to purchase those shares". (26) Asquith by vouching for his honesty, saved Isaacs's career. However, he could not do anything about the rumours that were spread about Isaacs. "As I walked across the lobbies or in the streets or to the courts... I could feel the pointing of the finger as I passed." (27)

On 30th June, 1913, the Select Committee provided three reports on the Marconi case. The majority (government) report claimed that no Minister had been influenced in the discharge of his public duties by any interest he might have had in any of the Marconi or other undertakings, or had utilized information coming to him from official sources for private investment or speculation.

The Minority (opposition) report criticised the whole handling of the share issue and found "grave impropriety" in the conduct of David Lloyd George, Rufus Isaacs and Alexander Murray, both in acquiring the shares at the advantageous price and in subsequent dealings in them. It also censored them for their lack of candour, especially Murray, who had refused to return to England to testify.

Although the chairman on the enquiry, Albert Spicer, signed the majority report, he also published his own report where he heavily criticised Rufus Isaacs for not disclosing at the beginning that he had bought shares in the Marconi Company. Spicer claimed that it was this lack of candour that resulted in the large number of rumours about the corrupt actions of the government ministers. (28)

Leonard Raven-Hill, Blameless Telegraphy (25th June, 1913)

In October, 1913, Rufus Isaacs, was appointed Lord Chief Justice of England. Newspapers complained that it appeared that he had been promoted as a reward for not disclosing the full truth about his share-dealings. However, it was reported by Lord Northcliffe that only five people had sent letters to his newspapers on the subject and "the whole Marconi business looms much larger in Downing Street than among the mass of the people". (29)

C. K. Chesterton, one of the men who exposed the scandal, agreed: "The object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption. It is now certain that the public does know. It is not so certain that the public does care." However, he did go on to argue that it did have a long-term impact on the British public: "It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence". (30)

In a speech at the National Liberal Club, David Lloyd George, attempted to defend the politicians involved in the Marconi case: "I should like to say one word about politicians generally. I think that they are a much-maligned race. Those who think that politicians are moved by sordid, pecuniary considerations know nothing of either politics or politicians. These are not the things that move us...The men who go into politics to make money are not politicians... We all have ambitions. I am not ashamed to say so. I speak as one who boasts: I have an ambition. I should like to be remembered amongst those who, in their day and generation, had at least done something to lift the poor out of the mire."

Lloyd George went on to argue that it was politicians like him who were protecting the public from other powerful forces: "The real peril in politics is not that individual politicians of high rank will attempt to make a packet for themselves. Read the history of England for the past fifty years. The real peril is that powerful interests will dominate the Legislature, will dominate the Executive, in order to carry through proposals which will prey upon the community. That is where tariffs - the landlord endowment - will come in." (31)

Marquess of Reading

In the new year's honours list of 1914, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Reading of Erleigh. In August he helped David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of Exchequer, during the financial crisis that was brought about by the outbreak of the First World War. In 1916 he presided over the treason trial of Sir Roger Casement. The main charge related to Casement's attempts while in Germany to recruit Irish prisoners of war to fight against England. (32)

In the political crisis of December 1916, he acted as intermediary between Lloyd George and Asquith in an attempt to keep both men in office; and after Lloyd George became prime minister, Reading tried to persuade Asquith to rejoin the cabinet as lord chancellor. In September 1917 Reading went to the United States with the special appointment of high commissioner. His task was to persuade the administration to integrate America's war effort more closely with that of the allies, to prioritize the deployment of military supplies and shipping, and to grant regular credits for the duration of the war. In this, an observer commented, he "achieved one of the biggest things of the war". (33)

In January 1921, Rufus Isaacs was appointed viceroy of India. He was in favour of increased participation by Indians in the government of the country and took a principled stand against racial discrimination. Reading wrote to Edwin Montagu, the secretary of state for India, with his thoughts on the subject: "I am convinced that we shall never persuade the Indian of the justice of our rule until we have overcome racial difficulties" and made it clear that he believed in eventual Indian self-government. (34)

Isaacs made a point of visiting Amritsar as a gesture of reconciliation for the massacre of 1919. He attempted to negotiate with Indian nationalists but in 1922 he ordered the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi. Isaacs remained loyal to David Lloyd George but disapproved strongly of his sacking of Montagu, after a telegram from him calling for withdrawal of allied troops from Constantinople. (35)

On his return to England in April 1926, Isaac was granted the title, the Marquess of Reading. He was the first commoner to rise so high since Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. Frances Lloyd George, has argued that one of the reasons for his success was that "ambition was his ruling quality". (36) John Maynard Keynes suggested that another reason was "terrified of identifying himself too decidedly with anything controversial". (37) He also made few enemies and was considered "a just and most likeable fellow" and "a lovable man". (38)

Although in his late sixties, Reading refused to retire and the boards of a number of companies (including the Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), National Provincial Bank and the London and Lancashire Insurance Company). After the death of Sir Alfred Mond in 1930, he became president of ICI. As head of the Liberal Party delegation, he played a leading role in the three round-table conferences on the Indian constitution in 1930–32. (39)

After forty-two years of marriage, Lady Reading died of cancer on 30th January 1930. The following year Reading married Stella Charnauld. He was nearly seventy-one and she was thirty-seven; she had served on his staff in India and thereafter as his private secretary. In 1931 Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister in a new National Government and appointed Reading as foreign secretary, something that "had always had a powerful attraction for him". (40)

The Marquess of Reading also became leader of the House of Lords. In this capacity he was responsible for steering legislation through the upper house, notably on the suspension of the gold standard. He resigned the Foreign Office after the General Election in October, 1931, and except for his work on the Government of India Act 1935, he retired from public life.

Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading, died following an attack of cardiac asthma, on 30th December 1935. His body was cremated and his ashes were interred near the remains of his first wife in the Golders Green Jewish Cemetery. "His estate was sworn for probate at £290,487 11s. 7d., a figure never exceeded hitherto by a practising member of the English bar". (41)

Primary Sources

(1) David Lloyd George, speech in the House of Commons (11th October, 1912)

The Honourable Member (George Lansbury) said something about the Government and he has talked about rumours. If the Honourable Member has any charge to make against the Government as a whole or against individual Members of it, I think it ought to be stated openly. The reason why the government wanted a frank discussion before going to Committee was because we wanted to bring here these rumours, these sinister rumours that have been passed from one foul lip to another behind the backs of the House.

(2) Rufus Isaacs, personal statement (11th October, 1912)

Never from the beginning... have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter.

(3) Leopold Maxse, evidence before the House of Commons committee (12th February, 1913)

One might have conceived that (the Ministers) might have appeared at the first sitting clamouring to state in the most categorical and emphatic manner that neither directly nor indirectly, in their names or other people's names, have they had any transactions whatsoever... In any Marconi company throughout the negotiations with the Government.

(4) The Spectator (11th October, 1913)

Lord Robert Cecil, addressing a Unionist meeting in North-West Manchester in support of the candidature of Mr. Hubert M. Wilson, dealt with the controversy between Mr. Lloyd George and members of his family on the Marconi question. The various charges which Mr. Lloyd. George bad brought against the Cecil family were irrelevant, and, he believed, entirely mistaken ; but whether mistaken or not, if the gentlemen attacked had broken every one of the ten Commandments, that did not alter his right or his duty to express his honest and impartial opinion on the conduct of Mr. Lloyd George in the Marconi transaction. He had never said or suggested that the transaction was corrupt ; but he did say that, if it was to be approved and recognized as the common practice among Government officials, then one of our greatest safeguards against corruption was absolutely destroyed. The transaction was bad and grossly improper, and it was made far worse by the fact that Mr. Lloyd George went about posing as an injured innocent. For a man in his position to defend that transaction was even worse than entering into it. Lord Robert Cecil added that the recklessness of the transaction, which was even more remarkable than its im- propriety, was characteristic of a good deal of the Govern- ment's proceedings, public as well as private. Recklessness was the chief characteristic of the Insurance Act and their policy in Ireland, and it also marked their attack on the Welsh Church.

(5) C. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (1936)

The object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption. It is now certain that the public does know. It is not so certain that the public does care...

It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence.

(6) David Lloyd George, speech in the National Liberal Club (1st July, 1913)

There is one martyrdom which I always thought was the least endurable of all. That was where the victim had his hands tied and arrows were shot into his body; and he could neither protect himself and tear them out nor sling them back. I can understand something of that now. For months every dastardly and cowardly journalist in the Tory Press shot his poisoned darts, knowing that the hands were tied behind the back by the principles of honour... My hands are free now - free to shield, free to smite, not for myself, but for the cause I believe in, which I have devoted my life to, and which I am going on with.

Before I do so, with your permission, I should like to sling a javelin or two at my persecutors ... when I was looking at the list of those who voted to turn us out of public life, I wondered how many of them would have gone into that lobby ifit had been a condition of being allowed to vote that they must show their pass-books for three years....

I should like to say one word about politicians generally. I think that they are a much-maligned race. Those who think that politicians are moved by sordid, pecuniary considerations know nothing ofeither politics or politicians. These are not the things that move us... In politics there is no cash, and if this campaign of calumny goes on there will be very little credit, either. There is no politician I know of who has attained a high position on either side... by capacity and strength of character - who would not in a business or profession make ten times as much as he makes in politics or is ever likely to make in politics... The men who go into politics to make money are not politicians. Men go in, if you like, for fame. Men go in, if you like, for ambition. Men go in from a sense of duty. But for mere cupidity, never!

We all have ambitions. I am not ashamed to say so. I speak as one who boasts: I have an ambition. I should like to be remembered amongst those who, in their day and generation, had at least done something to lift the poor out of the mire...The real peril in politics is not that individual politicians ofhigh rank will attempt to make a packet for themselves. Read the history of England for the past fifty years. The real peril is that powerful interests will dominate the Legislature, will dominate the Executive, in order to carry through proposals which will prey upon the community. That is where tariffs - the landlord endowment - will come in.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)