Alexander Murray, 1st Baron of Elibank

Alexander Murray, the eldest son in the family of four sons and five daughters of Commander Montolieu Fox Oliphant Murray, was born in Folkestone on 12th April, 1870. He was educated at Cheltenham College (1882–8) and was later employed as assistant private secretary at the Colonial Office (1892–5). (1)

Murray was an active member of the Liberal Party and in October 1900 he was elected for Midlothian but in 1906 he moved to Peebles and Selkirk. In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 397 seats (48.9%) compared to the Conservative Party's 156 seats (43.4%). In the landslide victory Balfour lost his seat as did most of his cabinet ministers. Margot Asquith wrote: "When the final figures of the Elections were published everyone was stunned, and it certainly looks as if it were the end of the great Tory Party as we have known it." (2)

In 1909 H. H. Asquith appointed him as under-secretary of state for India. The following year he became Liberal Chief Whip. During the next few years he became a loyal supporter of David Lloyd George and played an important role in the struggle with the House of Lords over the passing of the 1911 Parliament Act. (3)

According to his biographer, John Grigg: "In these difficult circumstances Murray was a highly effective operator, with a gift for backstage negotiation and intrigue much assisted by his natural bonhomie. He was liked by politicians of all parties and factions." (4) The journalist, John A. Spender, pointed out: "His ample figure and full-moon face, with its fringe of curls, were always a pleasant vision, and he had a persuasive manner that was hard to resist… his chronic good humour soothed many savage breasts". (5)

Alexander Murray and the Marconi Scandle

H. H. Asquith had been urged by senior members of the military to set up an British Empire chain of wireless telegraphy. Herbert Samuel, the Postmaster-General, began negotiating with several companies who could provide this service. This included the English Marconi Company, whose managing director was Godfrey Isaacs, the brother of Rufus Isaacs, the Attorney General. (6)

Godfrey Isaacs, was also on the board of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, that controlled the company operating in London. Isaacs had been given responsibility for selling 50,000 shares in the company to English investors before they became available to the general public. He advised his brother, Rufus Isaacs, to buy 10,000 of these shares at £2 apiece. He shared this information with Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, the Chief Whip, and they both purchased 1,000 shares at the same price. On 18th April 1912 Murray also bought 2,000 shares for the Liberal Party. (7)

These shares were not available on the British stock market. On 19th April, the first day that shares in the Marconi Company of America were available in London, the shares opened at £3 and ended the day at £4. The main reason for this was the news that Herbert Samuel was in negotiations with the English Marconi Company to provide a wireless-telegraphy system for the British Empire. Rufus Isaacs now sold all his shares for a profit of £20,000. Whereas his fellow government ministers, Lloyd George and Alexander Murray, sold half their shares and therefore got the other half for free. Lloyd George then used this money to buy another 1,500 shares in the company. (8)

Cecil Chesterton, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc were involved with a new journal called The Eye-Witness. It was later pointed out that "the object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption". The editor wrote to his mother, Lloyd George has been dealing on the Stock Exchange heavily to his advantage with private political information". They immediately began to investigate the case. (9)

On 19th July, 1912, Herbert Samuel announced that a contract had been agreed with the English Marconi Company. A couple of days later, W. R. Lawson, wrote in the weekly Outlook Magazine: "The Marconi Company has from its birth been a child of darkness... Its relations with certain Ministers have not always been purely official or political." (10)

Whereas the rest of the mainstream media ignored the story, over the next few weeks The Eye-Witness produced a series of articles on the subject. It suggested that Rufus Isaacs had made £160,000 out of the deal. It was also claimed that Alexander Murray, David Lloyd George, Godfrey Isaacs and Herbert Samuel had profited by buying shares based on knowledge of the government contract. (11)

The defenders of Lloyd George, Isaacs, Murray and Samuel, accused the magazine of anti-semitism, pointing out that three of the men named were Jewish. "They were all victims of the disease of the heart known as anti-semitism. It was a gift to them that the Attorney-General and his brother had the name of Isaacs, and the added bonus that the Postmaster General, who had negotiated the contract, was called Samuel." (12)

H. H. Asquith called a meeting with the accused men and discussed the possibility of legal action against the magazine. It was Asquith who eventually advised against this: "I suspect that Eyewitness has a very meagre circulation. I notice only one page of advertisements and then by Belloc's publishers. Prosecution would secure it notoriety which might yield subscribers." (13)

Resigns from the House of Commons

Alexander Murray resigned from the House of Commons on 7th August, 1912. Later that week he was raised to the peerage as Baron Murray of Elibank. Officially he left Parliament because he needed to rehabilitate the Elibank estates which his father had made over to him. Soon afterwards the Liberal industrialist Weetman Pearson sent him on business to Bogotá in Columbia. (14)

A debate on the Marconi contract took place on 11th October, 1912. Herbert Samuel explained that Marconi was the company best qualified to do the job and several Conservative MPs made speeches where they agreed with the government over this issue. The only dissenting voice was George Lansbury, the Labour MP, who argued that there had been "scandalous gambling in Marconi shares." (15)

David Lloyd George responded by attacking those who had spread untrue stories about his share dealings: "The Honourable Member (George Lansbury) said something about the Government and he has talked about rumours. If the Honourable Member has any charge to make against the Government as a whole or against individual Members of it, I think it ought to be stated openly. The reason why the government wanted a frank discussion before going to Committee was because we wanted to bring here these rumours, these sinister rumours that have been passed from one foul lip to another behind the backs of the House." (16)

Later that day, Rufus Isaacs issued a statement about his share-dealings. "Never from the beginning... have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter". (17)

Leopold Maxse, the editor of The National Review, pointed out that Isaacs had been careful in his use of words. He speculated why he said that he had not purchased shares in "that company" rather than the "Marconi company". Maxse pointed out: "One might have conceived that (the Ministers) might have appeared at the first sitting clamouring to state in the most categorical and emphatic manner that neither directly nor indirectly, in their names or other people's names, have they had any transactions whatsoever... In any Marconi company throughout thc negotiations with the Government". (18)

Asquith announced that he would set-up a committee to look into the possibility of insider dealings. The committee had six Liberals (including the chairman, Albert Spicer), two Irish Nationalists and one Labour MP, which provided a majority over six Conservatives. The committee took evidence from witnesses for the next six months and caused the Government a great deal of embarrassment. (19)

On 14th February, 1913, the French newspaper, Le Matin, reported that Herbert Samuel, David Lloyd George and Rufus Isaacs, had purchased Marconi shares at £2 and sold them when they reached the value of £8. When it was pointed out that this was not true, the newspaper published a retraction and an apology. However, on the advice of Winston Churchill, they decided to take legal action against the newspaper.

Churchill argued that this would provide an opportunity to shape the consciousness of the general public. He suggested that the men should employ two barristers, Frederick Smith and Edward Carson, who were members of the Conservative Party: "The public was bound to notice that the integrity of two Liberal ministers was being defended by normally partisan members of the Conservative Party, and their appearance on behalf of Isaacs and Samuel would make it impossible for them to attack either man in the House of Commons debate which would surely follow." (20)

Churchill also had a meeting with Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times and The Daily Mail and persuaded him to treat the accused men "gently" in his newspapers. (21) However, other newspapers were less kind and gave a great deal of coverage to the critics of the government. For example, The Spectator, reported a speech made by Robert Cecil, where he argued: "It was his duty to express his honest and impartial opinion on the conduct of Mr. Lloyd George in the Marconi transaction. He had never said or suggested that the transaction was corrupt; but he did say that, if it was to be approved and recognized as the common practice among Government officials, then one of our greatest safeguards against corruption was absolutely destroyed. The transaction was bad and grossly improper, and it was made far worse by the fact that Mr. Lloyd George went about posing as an injured innocent. For a man in his position to defend that transaction was even worse than entering into it." (22)

During the House of Commons investigation the three accused Liberal MPs admitted they had purchased shares in the Marconi Company of America. However, as David Lloyd George pointed out, he had held no shares in any company which did business with the government and that he had never made improper use of official information. He ridiculed the charges which were made against him - some of which he invented, for example, the claim that he had made a profit of £60,000 on a speculative investment or that owned a villa in France. (23)

Purchased Shares for the Liberal Party

Alexander Murray was unable to appear before the Marconi Enquiry because he was still in Bogotá. However, during the investigation, Murray's stockbroker was declared bankrupt and, in consequence, his account books and business papers were open to public examination. They revealed that Murray had not only purchased 2,500 shares in the American Marconi Company, but had invested £9,000 in the company on behalf of the Liberal Party. (24)

H. H. Asquith and Percy Illingworth, the new Chief Whip, denied knowledge of these shares. According to George Riddell, a close friend of both men, Asquith and Illingworth had known about this "for some time". (25) John Grigg, the author of Lloyd George, From Peace To War 1912-1916 (1985), has argued that Asquith was also aware of these shares and this explains why he was so keen to cover-up the story. "If he had shown any sign of abandoning them, they might have contemplating abandoning him, and vice versa... there was probably a mutual recognition of the need for solidarity in a situation where the abandonment of one might well have led to the ruin of all." (26)

On 30th June, 1913, the Select Committee provided three reports on the Marconi case. The majority (government) report claimed that no Minister had been influenced in the discharge of his public duties by any interest he might have had in any of the Marconi or other undertakings, or had utilized information coming to him from official sources for private investment or speculation.

The Minority (opposition) report criticised the whole handling of the share issue and found "grave impropriety" in the conduct of David Lloyd George, Rufus Isaacs and Alexander Murray, both in acquiring the shares at the advantageous price and in subsequent dealings in them. It also censored them for their lack of candour, especially Murray, who had refused to return to England to testify.

Although the chairman on the enquiry, Albert Spicer, signed the majority report, he also published his own report where he heavily criticised Rufus Isaacs for not disclosing at the beginning that he had bought shares in the Marconi Company. Spicer claimed that it was this lack of candour that resulted in the large number of rumours about the corrupt actions of the government ministers. (27)

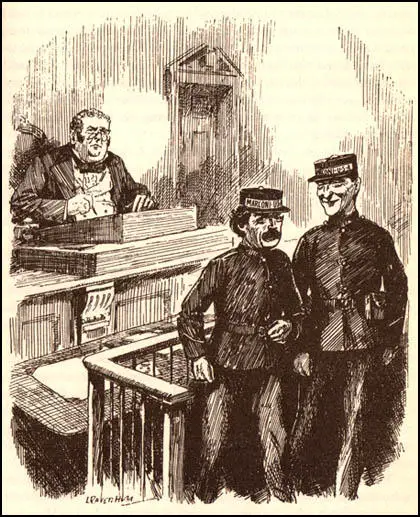

Leonard Raven-Hill, Blameless Telegraphy (25th June, 1913)

C. K. Chesterton, one of the men who exposed the scandal, agreed: "The object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption. It is now certain that the public does know. It is not so certain that the public does care." However, he did go on to argue that it did have a long-term impact on the British public: "It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence". (28)

Alexander Murray, 1st Baron Murray of Elibank, died on 13th September 1920. He had no children and the barony conferred on him became extinct.

Primary Sources

(1) Rufus Isaacs, personal statement (11th October, 1912)

Never from the beginning... have I had one single transaction with the shares of that company. I am not only speaking for myself but also speaking on behalf, I know, of both my Right Honourable Friends the Postmaster General and the Chancellor of the Exchequer who, in some way or another, in some of the articles, have been brought into this matter.

(2) Leopold Maxse, evidence before the House of Commons committee (12th February, 1913)

One might have conceived that (the Ministers) might have appeared at the first sitting clamouring to state in the most categorical and emphatic manner that neither directly nor indirectly, in their names or other people's names, have they had any transactions whatsoever... In any Marconi company throughout the negotiations with the Government.

(3) C. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (1936)

The object of the Eye-Witness was to make the English public know and care about the perils of political corruption. It is now certain that the public does know. It is not so certain that the public does care...

It is the fashion to divide recent history into Pre-War and Post-War conditions. I believe it is almost as essential to divide them into Pre-Marconi and Post-Marconi days. It was during the agitations upon that affair that the ordinary English citizen lost his invincible ignorance; or, in ordinary language, his innocence.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)