David Greenglass

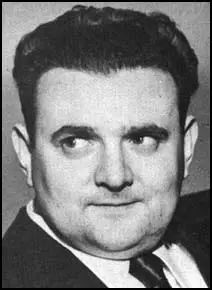

David Greenglass, the brother of Ethel Greenglass, was born in New York City on 2nd March, 1922. He became a machinist after learning his trade at Manhattan's Haaren Aviation High School. (1)

Greenglass joined the Young Communist League (YCL) and in 1942 he married Ruth Printz, a fellow member of the YCL. His sister married Julius Rosenberg, who was a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA).

In 1943 Greenglass joined the United States Army. A year later he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and assigned to the Manhattan Project based at Los Alamos. He worked in the Los Angeles Technical Area doing research involving high explosives. Greenglass worked according to the verbal instructions or sketches of scientists working on the project.

Julius Rosenberg became a Soviet agent working under Alexander Feklissov. In September 1944, Rosenberg suggested to Feklissov that he should consider recruiting his brother-in-law, David Greenglass and his wife, Ruth Greenglass. Feklissov met the couple and on 21st September, he reported to Moscow: "They are young, intelligent, capable, and politically developed people, strongly believing in the cause of communism and wishing to do their best to help our country as much as possible. They are undoubtedly devoted to us (the Soviet Union)." (2) Davidwrotetohiswife: "My darling, I most certainly will be glad to be part of the community project (espionage) that Julius and his friends (the Russians) have in mind." (3) Other members of the network included Greenglass's sister, Ethel Rosenberg. Alexander Feklissov recorded details of a meeting he had with the group: "Julius inquired of Ruth how she felt about the Soviet Union and how deep in general her Communist convictions went, whereupon she replied without hesitation that, to her, socialism was the sole hope of the world and the Soviet Union commanded her deepest admiration... Julius then explained his connections with certain people interested in supplying the Soviet Union with urgently needed technical information it could not obtain through the regular channels and impressed upon her the tremendous importance of the project in which David is now at work.... Ethel here interposed to stress the need for the utmost care and caution in informing David of the work in which Julius was engaged and that, for his own safety, all other political discussion and activity on his part should be subdued." (4) Alexander Feklissov reported that in January 1945, Rosenberg and Greenglass met to discuss their attempts to obtain information on the Manhattan Project. "(Julius Rosenberg) and (David Greenglass) met at the flat of (Greenglass's) mother... (Rosenberg's) wife and (Greenglass) are brother and sister. After a conversation in which (Greenglass) confirmed his consent to pass us data about work in Camp 2... (Rosenberg) discussed with him a list of questions to which it would be helpful to have answers... (Greenglass) has the rank of sergeant. He works in the camp as a mechanic, carrying out various instructions from his superiors. The place where (Greenglass) works is a plant where various devices for measuring and studying the explosive power of various explosives in different forms (lenses) are being produced." (5) Greenglass later claimed that as a result of this meeting he verbally described the "atom bomb" to Rosenberg. He also prepared some sketches and provided a written description of the lens mold experiments and a list of scientists working on the project. He was also asked the names of "some possible recruits... people who seemed sympathetic with Communism." Julius Rosenberg complained about his handwriting and arranged for Ethel Rosenberg to "type it up". According to Kathryn S. Olmsted: "Greenglass's knowledge was crude compared to the disquisitions on nuclear physics that the Russians received from Fuchs." (6) The Soviet spy network suffered a set-back when Julius Rosenberg, was sacked from the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, when they discovered that he had been a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). (7) NKVD headquarters in Moscow sent Leonid Kvasnikov a message on 23rd February, 1945: "The latest events with (Julius Rosenberg), his having been fired, are highly serious and demand on our part, first, a correct assessment of what happened, and second, a decision about (Rosenberg's) role in future. Deciding the latter, we should proceed from the fact that, in him, we have a man devoted to us, whom we can trust completely, a man who by his practical activities for several years has shown how strong is his desire to help our country. Besides, in (Rosenberg) we have a capable agent who knows how to work with people and has solid experience in recruiting new agents." (8) Kvasnikov's main concern was that the FBI had discovered that Rosenberg was a spy. To protect the rest of the network, Feklissov was told not to have any contact with Rosenberg. However, the NKVD continued to pay Rosenberg "maintenance" and was warned not to take any important decisions about his future work without their consent. Eventually they gave him permission to take "a job as a radar specialist with Western Electric, designing systems for the B-29 bomber." (9) After the war Rosenberg established a small surplus products business and a machine shop, in which David Greenglass invested. (10) Rosenberg lived with his wife and two children in Knickerbocker Village. He continued working as a Soviet spy. According to one decoded message he "continued fulfilling the duties of a group handler, maintaining contact with comrades, rendering them moral and material contact with comrades, rendering them moral and material help while gathering valuable scientific and technical information." (11) David Greenglass also carried on providing information for the Soviets. He worked as a mechanic at a Brooklyn company that assembled radar stabilizers for tank guns. Greenglass reported that "the idea of this device is that it must keep the gun constantly directed at the target regardless of the tank's vibrations while moving during battle." Greengrass offered to take a camera into the top-security plant to photograph drawings. However, his Soviet handlers rejected the idea as too dangerous. (12) Alexander Feklissov returned to the Soviet Union in February 1947. In a memorandum summarizing his work, he suggested that the Soviets should use David Greenglass and Ruth Greenglass as couriers and group handlers, roles similar to those previously performed by Rosenberg. Headquarters agreed: "(Greenglass), although he has the possibility of returning to work at an extremely important institution on Enormoz because of his limited education will not be able to obtain a position in which he could become an independent source of information in which we are interested." (13) On 12th September 1949, MI5 was sent documents that had been uncovered by the Venona Project that suggested that Klaus Fuchs was a Soviet spy. His telephones were tapped and his correspondence intercepted at both his home and office. Concealed microphones were installed in Fuchs's home in Harwell. Fuchs was tailed by B4 surveillance teams, who reported that he was difficult to follow. Although they discovered he was having an affair with the wife of his line manager, the investigation failed to produce any evidence of espionage. Klaus Fuchs was interviewed by MI5 officers but he denied any involvement in espionage and the intelligence services did not have enough evidence to have him arrested and charged with spying. Jim Skardon later recalled: "He (Klaus Fuchs) was obviously under considerable mental stress. I suggested that he should unburden his mind and clear his conscience by telling me the full story." Fuchs replied "I will never be persuaded by you to talk." The two men then went to lunch: "During the meal he seemed to be resolving the matter and to be considerably abstracted... He suggested that we should hurry back to his house. On arrival he said that he had decided it would be in his best interests to answer my questions. I then put certain questions to him and in reply he told me that he was engaged in espionage from mid 1942 until about a year ago. He said there was a continuous passing of information relating to atomic energy at irregular but frequent meetings." (14) Fuchs explained to Skardon: "Since that time I have had continuous contact with the persons who were completely unknown to me, except that I knew they would hand whatever information I gave them to the Russian authorities. At that time I had complete confidence in Russian policy and I believed that the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death. I had therefore, no hesitation in giving all the information I had, even though occasionally I tried to concentrate mainly on giving information about the results of my own work. There is nobody I know by name who is concerned with collecting information for the Russian authorities. There are people whom I know by sight whom I trusted with my life." (15) A few days later J. Edgar Hoover informed President Harry S. Truman that "we have just gotten word from England that we have gotten a full confession from one of the top scientists, who worked over here, that he gave the complete know-how of the atom bomb to the Russians." (16) As Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) pointed out: "What Fuchs had failed to realize was that, but for his confession, there would have been no case against him, Skardon's knowledge of his espionage, which had so impressed him, derived from... Verona... and unusable in court." (17) Klaus Fuchs was interviewed by MI5 about his Soviet contacts. It was later recorded that: "In the course of investigation, Fuchs was shown two American motion picture films of Harry Gold. In the first, Gold was shown on an American city street and impressed Fuchs as a man in a state of nervous excitement being chased.... After seeing the film... Fuchs identified Gold and gave testimony about him." (18) The FBI interviewed Gold about Fuchs. At first he denied knowing him. However, he suddenly broke down and made a full confession. On 23rd May, 1950, Gold appeared in court and was charged with conspiring with others to obtain secret information for the Soviet Union from Klaus Fuchs. Bail was set at $100,000 and a hearing scheduled for 12th June. The following day the newspapers reported that Gold had been arrested on evidence provided by Fuchs. (19) According to Alexander Feklissov, the main concern was to rescue Julius Rosenberg: "The main task from the Center's point of view was to get the key members of the network out, namely Julius Rosenberg and his family.... All necessary documents were ready. Gavriil Panchenko, Julius' case officer, had an urgent meeting with him, telling him to leave the United States as soon as possible. Rosenberg refused; he felt he couldn't leave his sister-in-law, Ruth Greenglass, by herself. She had been hospitalized because of burns to her body and was pregnant." (20) On 16th June, 1950, David Greenglass was arrested. The New York Tribune quoted him as saying: "I felt it was gross negligence on the part of the United States not to give Russia the information about the atom bomb because he was an ally." (21) According to the New York Times, while waiting to be arraigned, "Greenglass appeared unconcerned, laughing and joking with an FBI agent. When he appeared before Commissioner McDonald... he paid more attention to reporters' notes than to the proceedings." (22) Greenglass's attorney said that he had considered suicide after hearing of Gold's arrest. He was also held on $1000,000 bail. On 6th July, 1950, the New Mexico federal grand jury indicted David Greenglass on a charge of conspiring to commit espionage in wartime on behalf of the Soviet Union. Specifically, he was accused of meeting with Harry Gold in Albuquerque on 3rd June, 1945, and producing "a sketch of a high explosive lens mold" and receiving $500 from Gold. It was clear that Gold had provided the evidence to convict Greenglass. The New York Daily Mirror reported on 13th July that Greenglass had decided to join Harry Gold and testify against other Soviet spies. "The possibility that alleged atomic spy David Greenglass has decided to tell what he knows about the relay of secret information to Russia was evidenced yesterday when U. S. Commissioner McDonald granted the ex-Army sergeant an adjornment of proceedings to move him to New Mexico for trial." (23) Four days later the FBI announced the arrest of Julius Rosenberg. The New York Times reported that Rosenberg was the "fourth American held as a atom spy".(24) The New York Daily News sent a journalist to Rosenberg's machinist shop. He claimed that the three employees were all non-union workers who had been warned by Rosenberg that there could be no vacations because the firm had made no money in the past year and a half. The employees also disclosed that at one time David Greenglass had worked at the shop as a business partner of Rosenberg. (25) Time Magazine noted that "alone of the four arrested so far, Rosenberg stoutly insisted on his innocence." (26) The Department of Justice issued a press release quoting J. Edgar Hoover as saying "that Rosenberg is another important link in the Soviet espionage apparatus which includes Dr. Klaus Fuchs, Harry Gold, David Greenglass and Alfred Dean Slack. Mr. Hoover revealed that Rosenberg recruited Greenglass... Rosenberg, in early 1945, made available to Greenglass while on furlough in New York City one half of an irregularly cut jello box top, the other half of which was given to Greenglass by Harry Gold in Albuquerque, New Mexico as a means of identifying Gold to Greenglass." The statement went onto say that Anatoli Yatskov, Vice Consul of the Soviet Consulate in New York City, paid money to the men. Hoover referred to "the gravity of Rosenberg's offense" and stated that Rosenberg had "aggressively sought ways and means to secretly conspire with the Soviet Government to the detriment of his own country." (27) Julius Rosenberg refused to implicate anybody else in spying for the Soviet Union. Joseph McCarthy had just launched his attack on a so-called group of communists based in Washington. Hoover saw the arrest of Rosenberg as a means of getting good publicity for the FBI. However, he was desperate to get Rosenberg to confess. Alan H. Belmont reported to Hoover: "Inasmuch as it appears that Rosenberg will not be cooperative and the indications are definite that he possesses the ifentity of a number of other individuals who have been engaged in Soviet espionage... New York should consider every possible means to bring pressure on Rosenberg to make him talk, including... a careful study of the involvement of Ethel Rosenberg in order that charges can be placed against her, if possible." (28) Hoover sent a memorandum to the US attorney general Howard McGrath saying: "There is no question that if Julius Rosenberg would furnish details of his extensive espionage activities it would be possible to proceed against other individuals. Proceeding against his wife might serve as a lever in these matters." (29) On 11th August, 1950, Ethel Rosenberg testified before a grand jury. She refused to answer all the questions and as she left the courthouse she was taken into custody by FBI agents. Her attorney asked the U.S. Commissioner to parole her in his custody over the weekend, so that she could make arrangements for her two young children. The request was denied. One of the prosecuting team commented that there "is ample evidence that Mrs. Rosenberg and her husband have been affiliated with Communist activities for a long period of time." (30) Rosenberg's two children, Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg, were looked after by her mother, Tessie Greenglass. Julius and Ethel were put under pressure to incriminate others involved in the spy ring. Neither offered any further information. On 10th October, 1950, David Greenglass, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Morton Sobell and Anatoli Yatskov were charged with espionage. On 18th October, Greenglass pleaded guilty. It soon became clear that he and his wife, Ruth Greenglass, had been offered a deal if they provided information against the Rosenbergs. This included a promise not to charge Ruth with being a member of the spy ring. Greenglass now changed his story. In his original statement, he said that he handed over atomic information to Julius on a street corner in New York. In his new interview, Greenglass claimed that the handover had taken place in the living room of the Rosenberg's New York flat. In her FBI interview Ruth argued that "Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it, and when he came out he told (Ethel) she had to type this info immediately. Ethel then sat down at the typewriter... and proceeded to type info which David had given to Julius". (31) The trial of Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell began on 6th March 1951. Irving Saypol opened the case: "The evidence will show that the loyalty and alliance of the Rosenbergs and Sobell were not to our country, but that it was to Communism, Communism in this country and Communism throughout the world... Sobell and Julius Rosenberg, classmates together in college, dedicated themselves to the cause of Communism... this love of Communism and the Soviet Union soon led them into a Soviet espionage ring... You will hear our Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Sobell reached into wartime projects and installations of the United States Government... to obtain... secret information... and speed it on its way to Russia.... We will prove that the Rosenbergs devised and put into operation, with the aid of Soviet... agents in the country, an elaborate scheme which enabled them to steal through David Greenglass this one weapon, that might well hold the key to the survival of this nation and means the peace of the world, the atomic bomb." (32) David Greenglass, who was examined by Roy Cohn, provided important evidence against the Rosenbergs. He claimed that his sister, Ethel, influenced him to become a Communist. He remembered having conversations with Ethel at their home in 1935 when he was thirteen or fourteen. She told him that she preferred Russian socialism to capitalism. Two years later, her boyfriend, Julius, also persuasively talked about the merits of Communism. As a result of these conversations he joined the Young Communist League (YCL). (33) Greenglass pointed out that Julius Rosenberg recruited him as a Soviet spy in September 1944. Over the next few months he provided some sketches and provided a written description of the lens mold experiments and a list of scientists working on the project. He was gave Rosenberg the names of "some possible recruits... people who seemed sympathetic with Communism." Greenglass also claimed that because of his poor handwriting his sister typed up some of the material. (34) In June 1945 Greenglass claimed that Harry Gold visited him. "There was a man standing in the hallway who asked if I were Mr. Greenglass, and I said yes. He steeped through the door and he said, Julius sent me... and I walked to my wife's purse, took out the wallet and took out the matched part of the Jello box." Gold then produced the other part and he and David checked the pieces and saw they fitted. Greenglass did not have the information ready and asked Gold to return in the afternoon. He then prepared sketches of lens mold experiments with written descriptive material. When he returned Greenglass gave him the material in an envelope. Gold also gave Greenglass an envelope containing $500. (35) Greenglass told the court that in February 1950, Julius Rosenberg came to see him. He gave him the news that Klaus Fuchs had been arrested and that he had made a full confession. This would mean that members of his Soviet spy network would also be arrested. According to Greenglass, Rosenberg suggested that he should leave the country. Greenglass replied: "Well, I told him that I would need money to pay my debts back... to leave with a clear head... I insisted on it, so he said he would get the money for me from the Russians." In May he gave him $1,000 and promised him $6,000 more. (He later gave him another $4,000.) Rosenberg also warned him that Harry Gold had been arrested and was also providing information about the spy ring. Rosenberg also said he had to flee as the FBI had identified Jacob Golos as a spy and he had been his main contact until his death in 1943. Greenglass was cross-examined by Emanuel Bloch and suggested that his hostility towards Rosenberg had been caused by their failed business venture: "Now, weren't there repeated quarrels between you and Julius when Julius accused you of trying to be a boss and not working on machines?" Greenglass replied: "There were quarrels of every type and every kind... arguments over personality... arguments over money... arguments over the way the shop was run... We remained as good friends in spite of the quarrels." Bloch asked him why he had punched Rosenberg while in a "candy shop." Greenglass admitted that "it was some violent quarrel over something in the business." Greenglass complained that he had lost all of his money in investing in Rosenberg's business. The New York Times reported that Ruth Greenglass, the mother of a boy, four, and a girl, ten months, was a "buxom and self-possessed brunette" but looked older and her twenty-six years. It added that she testified "in seemingly eager, rapid fashion." (36) Ruth Greenglass recalled a conversation she had with Julius Rosenberg in November 1944: "Julius said that I might have noticed that for some time he and Ethel had not been actively pursuing any Communist Party activities, that they didn't buy the Daily Worker at the usual newsstand; that for two years he had been trying to get in touch with people who would assist him to be able to help the Russian people more directly other than just his membership in the Communist Party... He said that his friends had told him that David was working on the atomic bomb, and he went on to tell me that the atomic bomb was the most destructive weapon used so far, that it had dangerous radiation effects that the United States and Britain were working on this project jointly and that he felt that the information should be shared with Russia, who was our ally at the time, because if all nations had the information then one nation couldn't use the bomb as a threat against another. He said that he wanted me to tell my husband, David, that he should give information to Julius to be passed on to the Russians." Ruth Greenglass admitted that in February 1945, Rosenberg paid her to go and live in Albuquerque so she was close to David Greenglass who was working in Los Alamos: "Julius said he would take care of my expenses; the money was no object; the important thing was for me to go to Albuquerque to live." Harry Gold would visit and exchange information for money. One payment in June was $500. She "deposited $400 in an Albuquerque bank, purchased a $50 defense bond (for $37.50)" and used the rest for "household expenses." (37) Ruth Greenglass testified that she saw a "mahogany console table" in the Rosenberg's apartment in 1946. "Julius said it was from his friend and it was a special kind of table, and he turned the table on its side." A portion of the table was hollow "for a lamp to fit underneath it so that the table could be used for photograph purposes." Rosenberg said he used the table to take "pictures on microfilm of the typewritten notes." Emanuel Bloch argued: "Is there anything here which in any way connects Rosenberg with this conspiracy? The FBI "stopped at nothing in their investigation... to try to find some piece of evidence that you could feel, that you could see, that would tie the Rosenbergs up with this case... and yet this is the... complete documentary evidence adduced by the Government... this case, therefore, against the Rosenbergs depends upon oral testimony." Bloch attacked David Greenglass, the main witness against the Rosenbergs. Greenglass was "a self-confessed espionage agent," was "repulsive... he smirked and he smiled... I wonder whether... you have ever come across a man, who comes around to bury his own sister and smiles." Bloch argued that Greenglass's "grudge against Rosenberg" over money was not enough to explain his testimony. The explanation was that Greenglass "loved his wife" and was "willing to bury his sister and his brother-in-law" to save her. The "Greenglass Plot" was to lessen his punishment by pointing his finger at someone else. Julius Rosenberg was a "clay pigeon" because he had been fired from his government job for being a member of the Communist Party of the United States in 1945. (38) In his reply, Irving Saypol, pointed out that "Mr Bloch had a lot of things to say about Greenglass... but the story of the Albuquerque meeting... does not come to you from Greenglass alone. Every word that David and Ruth Greenglass spoke on this stand about that incident was corroborated by Harry Gold... a man concerning whom there cannot even be a suggestion of motive... He had been sentenced to thirty years... He can gain nothing from testifying as he did in this courtroom and tried to make amends. Harry Gold, who furnished the absolute corroboration of the testimony of the Greenglasses, forged the necessary link in the chain that points indisputably to the guilt of the Rosenbergs." In his summing up Judge Irving Kaufman was considered by many to have been highly subjective: "Judge Kaufman tied the crimes the Rosenbergs were being accused of to their ideas and the fact that they were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. He stated that they had given the atomic bomb to the Russians, which had triggered Communist aggression in Korea resulting in over 50,000 American casualties. He added that, because of their treason, the Soviet Union was threatening America with an atomic attack and this made it necessary for the United States to spend enormous amounts of money to build underground bomb shelters." (39) The jury found all three defendants guilty. Thanking the jurors, Judge Kaufman, told them: "My own opinion is that your verdict is a correct verdict... The thought that citizens of our country would lend themselves to the destruction of their own country by the most destructive weapons known to man is so shocking that I can't find words to describe this loathsome offense." (40) Judge Kaufman sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the death penalty and Morton Sobell to thirty years in prison. A large number of people were shocked by the severity of the sentence as they had not been found guilty of treason. In fact, they had been tried under the terms of the Espionage Act that had been passed in 1917 to deal with the American anti-war movement. Under the terms of this act, it was a crime to pass secrets to the enemy whereas these secrets had gone to an ally, the Soviet Union. During the Second World War several American citizens were convicted of passing information to Nazi Germany. Yet none of these people were executed. Irving Saypol opened the sentencing proceedings for David Greenglass by saying that the sentences imposed on Julius Rosenberg, Ethel Rosenberg and Morton Sobell "yesterday are substantially in accord with my views". He recommended that Judge Irving Kaufman demonstrate "the broad tolerance of the Court in the presence of penitence, contriteness, remorse and belated truth" and sentence Greenglass to fifteen years. Greenglass's lawyer, Oetje John Rogge, strongly disagreed with Saypol "as to what mercy means in this case." Rogge told the Court that Greenglass had been seduced into this conspiracy by Julius Rosenberg and only agreed because of his "fuzzy thinking" on the subject of the Soviet Union. He recommended a "light" sentence and a "pat on the back" for him, so as to encourage others to come forward with information on spying. Judge Kaufman responded: "I like to think that neither do I ever mete out a light sentence, nor a heavy sentence, but rather a just sentence." Turning to Greenglass, he added: "The fact that I am about to show you some consideration does not mean that I condone your acts or that I mimimize them in any respect... I must, however, recognize the help given by you in apprehending and bringing to justice the arch criminals in this nefarious scheme.. It is the judgment of this Court that I shall follow the recommendation of the government and sentence you to fifteen years in prison." (41) It seems that Ruth Greenglass was taken by surprise by the length of the sentence. The New York Times reported: "As the last words fell, Ruth Greenglass almost toppled from her front-row seat on the left of the courtroom. After a stiffening shudder, the defendant's twenty-seven-year-old wife dropped her bare head forward to the rail and gripped hard with her right hand to steady herself." (42) He was released after only serving ten years. Greenglass went to live with his wife in the New York City area under an assumed name. In 1997 Alexander Feklissov, gave an interview to the The Washington Post where he claimed that Julius Rosenberg passed valuable secrets about U.S. military electronics but played only a peripheral role in Soviet atomic espionage. And he said Ethel Rosenberg did not actively spy but probably was aware that her husband was involved. Feklissov said neither he nor any other Soviet intelligence agent met Ethel Rosenberg. "She had nothing to do with this. She was completely innocent." (43) In December 2001, Sam Roberts, a New York Times reporter, traced David Greenglass, who was living under an assumed name with Ruth Greenglass. Interviewed on television under a heavy disguise, he acknowledged that his and his wife's court statements had been untrue. "Julius asked me to write up some stuff, which I did, and then he had it typed. I don't know who typed it, frankly. And to this day I can't even remember that the typing took place. But somebody typed it. Now I'm not sure who it was and I don't even think it was done while we were there." David Greenglass said he had no regrets about his testimony that resulted in the execution of Ethel Rosenberg. "As a spy who turned his family in, I don't care. I sleep very well. I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister... You know, I seldom use the word sister anymore; I've just wiped it out of my mind. My wife put her in it. So what am I going to do, call my wife a liar? My wife is my wife... My wife says, 'Look, we're still alive'." (44) David Greenglass died on 1st July, 2014.David Greenglass - Soviet Spy

Business Venture

Arrest of Klaus Fuchs

Arrest of David Greenglass

Arrest of Julius Rosenberg

Trial of the Rosenbergs

Testimony of Ruth Greenglass

Summations & Verdict

The Imprisonment of David Greenglass

Primary Sources

(1) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy (2009)

The Soviets also received important military information from a ring of communist spies in New York headed by Julius Rosenberg. A thin, intense Stalinist, Rosenberg recruited a group of his fellow engineers, many of them friends from his college days in the Young Communist League. Rosenberg also recruited his brother-in-law, David Greenglass, after the young sergeant was stationed at Los Alamos, though Greenglass's knowledge was crude compared to the disquisitions on nuclear physics that the Russians received from Fuchs. Julius's wife, Ethel, helped him with his espionage, but was not a major spy in her own right.

(2) Alexander Feklissov report to NKVD headquarters (January 1945)

(Julius Rosenberg) and (David Greenglass) met at the flat of (Greenglass's) mother... (Rosenberg's) wife and (Greenglass) are brother and sister. After a conversation in which (Greenglass) confirmed his consent to pass us data about work in Camp 2... (Rosenberg) discussed with him a list of questions to which it would be helpful to have answers... (Greenglass) has the rank of sergeant. He works in the camp as a mechanic, carrying out various instructions from his superiors. The place where (Greenglass) works is a plant where various devices for measuring and studying the explosive power of various explosives in different forms (lenses) are being produced.

(3) Judge Irving Kaufman, sentencing Ethel Greenglass and Julius Rosenberg to death (5th April, 1951)

The evidence indicated quite clearly that Julius Rosenberg was the prime mover in this conspiracy. However, let no mistake be made about the role which his wife, Ethel Rosenberg, played in this conspiracy. Instead of deterring him from pursuing his ignoble cause, she encouraged and assisted the cause. She was a mature woman - almost three years older than her husband and almost seven years older than her younger brother. She was a full-fledged partner in this crime.

Indeed the defendants Julius and Ethel Rosenberg placed their devotion to their cause above their own personal safety and were conscious that they were sacrificing their own children, should their misdeeds be detected - all of which did not deter them from pursuing their course. Love for their cause dominated their lives - it was even greater than their love for their children.

The sentence of the Court upon Julius and Ethel Rosenberg is, for the crime for which you have been convicted, you are hereby sentenced to the punishment to death, and it is ordered upon some day within the week beginning with Monday, May 21st, you shall be executed according to law.

(4) Martin Weil, The Washington Post (3rd November, 2007)

Alexander Feklisov, 93, who was regarded as one of the Soviet Union's principal Cold War espionage agents, with connections to the Rosenberg spy case and atomic secrets, died in Russia on Oct. 26.

A Russian news agency said his death was reported by a spokesman for the Russian intelligence service.

In addition to obtaining key secrets of western technology for the Soviets during and after World War II, Mr. Feklisov was often credited with helping to defuse the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which brought the world close to nuclear war. He was then on his second tour in the United States, serving as Soviet intelligence chief, with an office in the Soviet Embassy on 16th Street NW, a few blocks from the White House.

For Mr. Feklisov, deception was a way of life. His employers were obsessively secretive. But revelations he made long after the events in question have won considerable acceptance.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Michael Dobbs, formerly a reporter for The Washington Post and now on contract to the newspaper, interviewed Mr. Feklisov.

Dobbs's story was published in 1997, around the time a TV documentary was shown about the former spy and four years before Mr. Feklisov's autobiography, The Man Behind the Rosenbergs, was published. Dobbs said this week that he believed Mr. Feklisov "was being pretty truthful," particularly in his account of his dealing with Julius Rosenberg.

Mr. Feklisov said there were dozens of meetings with Julius Rosenberg from 1943 to 1946. But he said Ethel Rosenberg never met with Soviet agents and took no direct part in her husband's spying.

Both Rosenbergs were executed in 1953 after a treason trial at which they were accused of giving the Soviets atomic bomb secrets. Their fate evoked protest around the world, and many insisted on their innocence.

In Mr. Feklisov's account, Julius Rosenberg was a dedicated communist, motivated by idealism. But Mr. Feklisov said Rosenberg, who was not a nuclear scientist, played only a peripheral role in atomic espionage.

Mr. Feklisov said Rosenberg did give him the key to another one of World War II's closely guarded secrets: the proximity fuse. This device vastly improved the effectiveness of artillery and antiaircraft fire by causing shells to detonate once they came close to their targets, rather than requiring direct hits.

A fully functioning fuse, inside a box, was turned over to Mr. Feklisov in a New York Automat in late 1944.

Important nuclear information was later passed through Mr. Feklisov to the Soviets by Klaus Fuchs, a nuclear scientist working in England who was a devoted communist. Historians have said that espionage advanced Soviet bomb development by 12 to 18 months.

In his activities, Mr. Feklisov, who used the code name Fomin, sometimes employed techniques made familiar in spy novels.

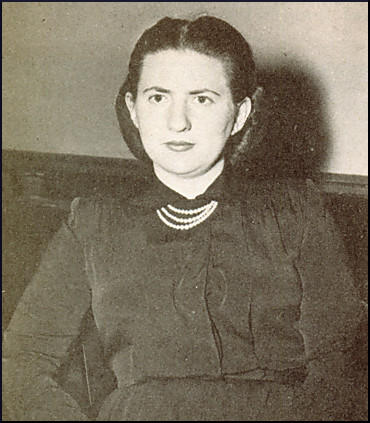

For example, he told Dobbs that when handing off contraband, he and those working for him "would arrange to meet in a place like Madison Square Garden or a cinema and brush up against each other very quickly."

During the 1962 missile crisis, the United States faced off with the Soviet Union after discovering that nuclear missiles had been delivered to Cuba. After days in which war seemed imminent, a plan was devised to resolve the situation.

Some accounts indicate that the way out was proposed informally by Mr. Feklisov to ABC news correspondent John Scali at the Occidental Restaurant on Pennsylvania Avenue NW. There, it has been written, he broached the idea that the missiles would be withdrawn if the United States pledged not to invade Cuba.

But Dobbs, who is writing a book on the missile crisis, said stories about Feklisov's being a "back channel" to Moscow "were overblown." Feklisov, he said, "never confirmed them."

Mr. Feklisov told Dobbs that he decided to tell of his association with Julius Rosenberg because he considered him a hero who had been abandoned by the Soviets. "My morality does not allow me to keep silent," he said.

Dobbs said that when Mr. Feklisov visited this country for the TV documentary, the former spy, an emotional man, visited Julius Rosenberg's grave and brought Russian earth to place on it.

(5) Michael Ellison, The Guardian (6th December, 2001)

One of the most enduring controversies of the cold war, the trial and executions of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg as Soviet spies, was revived last night when her convicted brother said that he had lied at the trial to save himself and his wife.

"As a spy who turned his family in, I don't care," David Greenglass, 79, said on his first public appearance for more than 40 years.

"I sleep very well. I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister."

Mr Greenglass, who lives under an assumed identity, was sentenced to 15 years and released from prison in 1960.

He said in a taped interview on last night's CBS television programme 60 Minutes that he, too, gave the Russians atomic secrets and information about a newly invented detonator.

He said he gave false testimony because he feared that his wife Ruth might be charged, and that he was encouraged by the prosecution to lie.

He gave the court the most damning evidence against his sister: that she had typed up his spying notes, intended for transmission to Moscow, on a Remington portable typewriter.

Now he says that this testimony was based on the recollection of his wife rather than his own first-hand knowledge.

"I don't know who typed it, frankly, and to this day I can't remember that the typing took place," he said last night. "I had no memory of that at all - none whatsoever."

(6) Harold Jackson, The Guardian (14th July, 2008)

David Greenglass, a technical sergeant involved in machining parts at the Manhattan Project, originally attracted the FBI's attention for stealing small quantities of uranium as a souvenir. Under questioning, he admitted acting as a Soviet spy at Los Alamos and named Julius Rosenberg as one of his contacts. But he flatly denied that his sister, Ethel, had ever been involved. Though he told the FBI at the time that his wife Ruth had acted as a courier, he said in his 2001 television interview that he had warned the bureau: "If you indict my wife you can forget it. I'll never say a word about anybody."

The difficulty with Hoover's proposed strategy of using Rosenberg's wife as a lever was that there was no evidence against her. Nonetheless, she was arrested and her two children were taken into care. The Rosenbergs' bail was set at $100,000 each, which they had no hope of raising, and the pressure on them to incriminate others increased. Neither offered any further information.

Ten days before the start of the trial, the FBI re-interviewed the Greenglasses. In his original statement, David had said that he handed over atomic information to Julius on a street corner in New York. In this new interview, he said that the handover had taken place in the living room of the Rosenbergs' New York flat. Ruth then elaborated on this by telling the FBI agents that "Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it, and when he came out he told [Ethel] she had to type this info immediately. Ethel then sat down at the typewriter ... and proceeded to type the info which David had given to Julius."

Ruth and her husband repeated this evidence in the witness box and it became the basis of Ethel's conviction as a co-conspirator. However, the court verdict failed to induce a confession from Julius, as Hoover had hoped it might. There were innumerable unsuccessful appeals, and up until the night of the execution President Dwight Eisenhower was on standby to commute one or both of the Rosenbergs' sentences. But the couple remained silent.

(7) Dennis Hevesi, The New York Times (10th July, 2008)

A main element in the prosecution was the threat of indictment, conviction and possible execution of Ethel Rosenberg as leverage to persuade Julius Rosenberg to confess and to implicate other collaborators. Those collaborators had already been identified, largely from what became known as the Venona transcripts, a trove of intercepted Soviet cables.

But with little more than a week before the trial was to start, on March 6, 1951, the government's case against Ethel Rosenberg remained flimsy, lacking evidence of an overt act to justify her conviction, much less her execution.

Prosecutors had been interrogating Ruth Greenglass since June 1950. In February 1951, she was interviewed again. After reminding her that she was still subject to indictment and that her husband had yet to be sentenced, the prosecutors extracted a recollection from her: that in the fall of 1945, Ethel Rosenberg had typed her brother's handwritten notes.

Soon after, confronted with his wife's account, David Greenglass told prosecutors that Ruth Greenglass had a very good memory and that if that was what she recalled of events six years earlier, she was probably right.

The transcripts of those two crucial interviews have never been released or even located in government files. But at the trial, David Greenglass testified that his sister had done the typing. Called to the stand, Ruth Greenglass corroborated her husband's testimony.

(8) Benjamin Weiser, New York Times (23rd July, 2008)

A federal judge in Manhattan, weighing the secrecy of the grand jury process against the interests of public accountability, refused on Tuesday to unseal the grand jury testimony of a critical witness in the Rosenberg atomic espionage case.

But with no objection from the government about the release of testimony from three dozen or so other witnesses, those records could be released soon.

The witness who objected to having his testimony made public, David Greenglass, the brother of Ethel Rosenberg, was a co-conspirator and a key government witness whose testimony helped convict Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. They were executed at Sing Sing on June 19, 1953.

Mr. Greenglass, now 86, is one of the most controversial figures in the enduring spy case, historians say, as years after his sister’s execution he recanted his testimony that she had typed some of his espionage notes. He had testified against her to spare his wife, Ruth, from prosecution, and is widely seen as helping to cause Ethel’s conviction and execution.

A group of historians had petitioned for the release of the still-secret testimony, running more than 1,000 pages, of the witnesses who appeared before the grand jury in the Rosenberg case and a related one in 1950 and 1951.

The government agreed to the unsealing of testimony from most of the witnesses, objecting only to that of about 10, including Mr. Greenglass, who were still alive and did not consent or could not be found.

In refusing to release Mr. Greenglass’s testimony while he is alive, Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein stressed the importance of grand jury secrecy as well as accountability.

But he added that not permitting others to disclose what a witness has said before the grand jury “is an abiding value that I must respect.”

Mr. Greenglass was not in court, but his lawyer, Daniel N. Arshack, wrote to Judge Hellerstein, saying that the circumstances that led to Mr. Greenglass’s testimony were “complex and emotionally wrought,” and had thrust him and his family “into an unwanted spotlight which has dogged their lives ever since.”

“The unequivocal and complete promise of secrecy,” Mr. Arshack wrote, “provided the protection that the guarantee of secrecy is designed to provide.”

Judge Hellerstein said that he would wait to rule on the other witnesses for whom the government was still objecting until further efforts were made to track them down or ascertain that they had died.

But he made it clear that he wanted that search to occur expeditiously, saying “time is precious” for historians and researchers.

The petitioners, led by the National Security Archives, a nonprofit group at George Washington University, had argued that the significance of the case, which they called “perhaps the defining moment of the early Cold War,” should trump the traditional confidentiality rules that govern the grand jury process.

The government, while not disputing the case’s historic importance, has said that the court should abide by the views of living witnesses who objected to the release of their testimony. Otherwise, the government said, witnesses could be discouraged from speaking candidly before grand juries in the future.

David C. Vladeck, a lawyer who argued for the petitioners, praised the outcome of the case and the expected release of the other testimony. “All of this is very good news,” he said.

He added that he was disappointed in the ruling on Mr. Greenglass, but said that “at some point we’ll get the records,” alluding to the government’s position that historians can renew their request after a witness’s death.

The historians supporting the release of the Rosenberg records hold diverse political views and opinions about the case. One of the petitioners is Sam Roberts, a reporter for The New York Times, who wrote a book on Mr. Greenglass.

One scholar who was not involved in the petition, David Oshinsky, said that even without release of the Greenglass testimony, the testimony of the other witnesses should help clear up questions about the evidence against Ethel Rosenberg.

“My sense is that what this may do is further implicate Julius while to some degree further exonerating Ethel,” said Mr. Oshinsky, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian.

He added that if there turned out to be very little other evidence against Ethel Rosenberg, “then the entire case does take a turn, and that is of vital importance.”