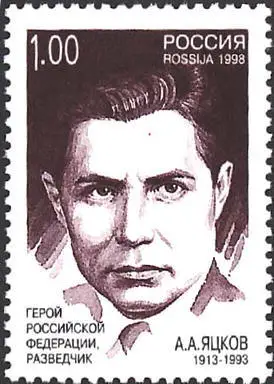

Anatoli Yatskov

Anatoli Yatskov was born in Russia on 31st May 1913. After attending university he joined the NKVD. In 1941 he was sent to the United States and took up the appointment as General Consul of the Soviet Union's delegation in New York City. (1)

In 1944 Yatskov became involved in the Soviet spy network that included Alexander Feklissov, Semyon Semyonov and Leonid Kvasnikov, that was attempting to steal atomic secrets from the United States. He became concerned about the role played by Harry Gold in his contacts with Klaus Fuchs. In 28th July, 1944, he reported: "At one time, when we instructed Gold to establish contact with (Fuchs), we drew special attention to the need for detailed accounts of (Fuchs's) work. After establishing his liaison with (Fuchs), we receive his information with every mail, but we do not have a single report from (Gold) about his work with (Fuchs) or about (Fuchs) himself. Missing also are precise data about where (Fuchs) works, his address, how and where meetings take place, (Gold's) impressions of (Fuchs), etc. Nor do we have the conditions of meeting (Fuchs) adopted by himself and (Gold in case of) sudden loss." (2)

Anatoli Yatskov in USA

Yatskov was also involved with Theodore Hall, one of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Hall suggested that it would look more natural if he had meetings with a woman. It was arranged for Lona Cohen to become his courier. Hall wrote out the information with milk on a newspaper (a variant of invisible ink). Anatoli Yatskov complained: "With our workload, this method of conveying material is extremely undesirable. We couldn't discern several words in the report, but there were not many such words; the material generally is highly valuable." (3) On 26th May, 1945 Leonid Kvasnikov was able to report to Pavel Fitin: "Theodore Hall's material contains: (a) A list of eight places where work on Enormoz is being carried out... (b) A brief description of the four methods of production of 25 - the diffusion, thermal diffusion, electromagnetic, and spectrographic methods. The material has not been fully worked over. We shall let you know the contents of the rest later." (4)

The Soviet government was devastated when the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th and 9th August, 1945. Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "On August 25, Kvasnikov responded that the station had not yet received agent reports on the explosions in Japan. As for Fuchs and Greenglass, their next meetings with Gold were scheduled for mid-September. Moscow found Kvasnikov's excuses unacceptable and reminded him on August 28 of the even greater future importance of information on atomic research, now that the Americans had produced the most destructive weapon known to humankind." (5)

Kvasnikov's boss, Pavel Fitin, wrote to Vsevolod Merkulov: "Practical use of the atomic bomb by the Americans means the completion of the first stage of enormous scientific-research work on the problem of releasing intra-atomic energy. The fact opens a new epoch in science and technology and will undoubtedly result in rapid development of the entire problem of Enormoz - using intra-atomic energy not only for military purposes but in the entire modern economy. All this gives the problem of Enormoz a leading place in our intelligence work and demands immediate measures to strengthen our technical intelligence." (6)

Anatoli Yatskov continued to seek information on the atom bomb and in September, 1945, he met with David Greenglass. "In our conversation, it was established that (Greenglass) worked in secondary workshops of the (New Mexico atomic camps), producing tools, instruments... and sometimes details for the (atomic bomb). Thus, for example, detonators for the fuse of the bomb's explosive were made in their workshop, and (Greenglass) passed to us a cartridge for such a detonator... Information about the (atomic bomb) he is giving us comes from stories of friends who work in the (New Mexico atomic camps)... (Greenglass) was assigned to gather detailed characteristics on people he considered suitable for drawing into our work." (7)

In October 1945 Yatskov had a meeting with Harry Gold after his return from Los Alamos. He complained that security surrounding the atomic camps was "much tougher than it was during his visit there in June. Local residents... treat outsiders very suspiciously." Klaus Fuchs gave Gold a copy of a memorandum that a number of scientist working on the Manhattan Project had sent to President Harry S. Truman. Yatskov sent a summary of the memorandum to Moscow: "This memorandum assesses the (atomic bomb) as a super-destructive means of war and expresses certainty in the possibility of exercising international control over the (bomb's) production." It urges creation of an international organization to control the use of atomic energy and purposes to let other countries know about secrets connected with the (bomb's) production." (8)

Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Bentley, confessed to the FBI she was a Soviet spy. On the 7th November 1945, she made a 107 page statement that named Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, William Remington, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Joseph Katz, William Ludwig Ullmann, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Abraham Brothman, Mary Price, Cedric Belfrage and Lauchlin Currie as Soviet spies. The following day J. Edgar Hoover, sent a message to Harry S. Truman confirming that an espionage ring was operating in the United States government. (9)

When Kim Philby told the NKVD that Bentley had provided the names of Soviet spies, Yatskov was ordered to break-off all contact with his agents. However, on 19th December, 1945, he did have a meeting with Harry Gold, who warned him that a member of his network, Abraham Brothman, had already been interviewed by the FBI. Gold insisted that Brothman knew him as "Frank Kessler" and did not know his address: "I said that in case (Brothman) confessed about (Gold's) existence and described... what he knew about him, the FBI would try to find him. (Gold) should know that these links to him come only from (Brothman) and must not worry, since the (FBI) knows nothing about him and his work... However, (Gold) must be on the alert and demonstrate tenfold prudence and attentiveness in everything." (10)

Harry Gold

Anatoli Yatskov now broke off all contact with Gold until another meeting took place on 26th December, 1946. As Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "Yatskov had not seen Gold for an entire year. By the time they concluded their conversations, the Soviet operative undoubtedly regretted his neglect. Gold had been fired from his job as a chemist at a sugar plant in March 1946 when the company laid off a number of employees because of business losses. He remained unemployed until May, when Abe Brothman hired him as a chief chemist in his company. In short, the NKGB's chief courier in America now worked daily for one of his own leading sources!" (11) Yatskov also discovered that Gold had become a close friend of Brothman and had told him his real name and address. Yatskov was outraged and rebuked Gold angrily for having violated all the rules of spying. Yatskov, aware that it was only a matter of time before he would be unmasked as a spy he immediately returned to the Soviet Union.

The FBI arrested Harry Gold and interviewed him about Klaus Fuchs. At first he denied knowing him. However, he suddenly broke down and made a full confession. On 23rd May, 1950, Gold appeared in court and was charged with conspiring with others to obtain secret information for the Soviet Union from Klaus Fuchs. Bail was set at $100,000 and a hearing scheduled for 12th June. The following day the newspapers reported that Gold had been arrested on evidence provided by Fuchs. (12)

Time Magazine reported: "That night his father a Russian-born cabinetmaker, and his brother, Joseph, 34, who had fought in the U.S. Army in World War II, heard astounding news - Harry Gold had been a spy for Russia." The journal quoted his father as saying "Harry was a good boy - maybe they gave him drugs." However, when his father and brother went to see him Gold confessed: "I've done something that can't be rubbed off." (13)

Gold pleaded guilty of conspiring with Yatskov, Klaus Fuchs and Semyon Semyonov to obtain atomic energy information for the Soviet Union. He appeared in court for sentencing on 7th December, 1950. Time Magazine commented: "There was something oddly inanimate about jail-pallid, soft-eyed little chemist Harry Gold... He had a strained unhealthy air and he sat almost immobile, with his eyes straight ahead." (14)

Gold made a statement before he was sentenced: "The most tormenting of all thoughts concerns the fact that those who meant so much to me have been the worst besmirched by my deeds. I refer here to this country, to my family and friends, to my former classmates... I have tried to make the greatest possible amends by disclosing every phase of my espionage activities, by identifying all of the persons involved, and by revealing every last scrap, shred and particle of evidence." (15)

Harry Gold was sentenced to thirty years imprisonment. The New York Times reported: "The severity of the penalty... came as a surprise to most of the 150 persons in the courtroom. The defendant... heard the penalty without any sign of emotion." (16) It was later revealed that Gold had not done a deal with the prosecution: "Harry Gold, who had apparently provided all the evidence against himself, had cooperated fully with the FBI and prosecution, had never bargained regarding his sentence and now accepted the severe one imposed on him with his customary selfless manner, announced through his attorney that there would be no appeal." (17)

Anatoli Yatskov died on 26th March, 1993.

Primary Sources

(1) Anatoli Yatskov, report on Harry Gold and Klaus Fuchs (28th July, 1944)

At one time, when we instructed Gold to establish contact with (Fuchs), we drew special attention to the need for detailed accounts of (Fuchs's) work. After establishing his liaison with (Fuchs), we receive his information with every mail, but we do not have a single report from (Gold) about his work with (Fuchs) or about (Fuchs) himself. Missing also are precise data about where (Fuchs) works, his address, how and where meetings take place, (Gold's) impressions of (Fuchs), etc. Nor do we have the conditions of meeting (Fuchs) adopted by himself and (Gold in case of) sudden loss.

(2) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999)

Yatskov had not seen Gold for an entire year. By the time they concluded their conversations, the Soviet operative undoubtedly regretted his neglect. Gold had been fired from his job as a chemist at a sugar plant in March 1946 when the company laid off a number of employees because of business losses. He remained unemployed until May, when Abe Brothman hired him as a chief chemist in his company. In short, the NKGB's chief courier in America now worked daily for one of his own leading sources!

References

(1) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 189

(2) Anatoli Yatskov, report on Harry Gold and Klaus Fuchs (28th July, 1944)

(3) Venona File 40594 page 130

(4) Leonid Kvasnikov, report to Pavel Fitin (26th May, 1945)

(5) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 211

(6) Venona File 40159 page 551

(7) Venona File 40594 pages 250-251

(8) Anatoli Yatskov, memorandum to Moscow (29th October, 1945)

(9) Edgar Hoover, memo to President Harry S. Truman (8th November 1945)

(10) Venona File 86194 page 365

(11) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 219

(12) New York Times (24th May, 1950)

(13) Time Magazine (5th June, 1950)

(14) Time Magazine (18th December, 1950)

(15) Harry Gold, testimony (9th December, 1950)

(16) New York Times (10th December, 1950)

(17) Walter Schneir and Miriam Schneir, Invitation to an Inquest (1983) page 117