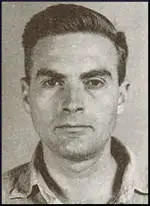

William Remington

William Remington, the son of Frederick C. Remington (1870–1956), was born in New York City on 25th October, 1917. "His father had been an executive in a large corporation, his mother an art teacher." (1) Remington was educated at Dartmouth College and Columbia University.

Remington developed left-wing political views. Remington argued that he had been greatly influenced by the Russian Revolution: "I thought Russia a great experiment: they were making great progress toward improvement of living standards and I liked what the Russians were proposing for collective security against Nazism and Fascism." (2) While he was at college he joined the Young Communist League, which was the official youth movement of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUS). (3)

Remington was an enthusiastic supporter of the New Deal and in 1936 he found temporary employment with the Tennessee Valley Authority. He met Ann Moos in the CPUS in 1936 and he married her three years later. He returned to Columbia University to work for a master's degree in economics. During this period he became close to Joseph North, the editor of the New Masses.

William Remington & the New Deal

Remington, an economist, he worked for the National Resources Planning Board and the Department of Commerce. When his boss, Thomas C. Blaisdell, became assistant of the director of the War Production Board in February 1942, he took Remington with him. The historian, Kathryn S. Olmsted, has argued: "Remington and his wife, Ann, longed to reestablish contact with the Party in Washington, but they knew that open membership would hurt Bill's career. As a solution some Party friends introduced them to a mysterious, redheaded man with an Eastern European accent." The man's real name was Jacob Golos and he was a Soviet spy. (4)

Golos passed Remington over to Elizabeth Bentley. Over the next two years, Bentley met Remington on a regular basis. She later recalled that he gave her classified information on aircraft production and testing. She claimed that "he was one of the most frightened people with whom I have ever had to deal". Eventually, he refused to meet Bentley and openly joined pro-Communist organizations in the hope that he would lessen his value as a spy. Bentley dismissed Remington as "a small boy trying to avoid moving the lawn or cleaning out the furnace when he would much rather go fishing." Bentley advised Golos that they should drop him but he insisted that they remained in contact as other powerful members of the network might be able to "push him into a really good position." (5)

Roy Cohn later argued: "Remington regularly handed Elizabeth Bentley documents and information from the War Production Board which she took to Golos in New York. He gave her material such as airplane production schedules. One item was unique. Remington had learned that the War Production Board was working on a secret process to produce synthetic rubber from garbage. The project was under careful and secret scrutiny by the Government and large sums of money were being expended on its research. Remington got hold of the formula of this secret process. He considered it one of his greatest achievements and emphasized its potential importance as he turned it over to Helen (Bentley)." (6)

Elizabeth Bentley

In 1944 Elizabeth Bentley left the Communist Party and the following year she considered telling the authorities about her spying activities. In August 1945 she was on holiday to Old Lyme. While in Connecticut she visited the FBI in New Haven. She was interviewed by Special Agent Edward Coady but she was reluctant to give any details of her fellow spies but did tell them that they she was vice-president of the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation and the company was being used to send information to the Soviet Union. Coady sent a memo to the New York City office suggesting that Bentley could be used as an informant. (7)

On 11th October 1945, Louis Budenz, the editor of the Daily Worker, announced that he was leaving the Communist Party of the United State and had rejoined "the faith of my fathers" because Communism "aims to establish tyranny over the human spirit". He also said that he intended to expose the "Communist menace". (8) Budenz knew that Bentley was a spy and four days later showed up at the FBI's New York office. Vsevolod Merkulov later wrote in a memo to Joseph Stalin that "Bentley's betrayal might have been caused by her fear of being unmasked by the renegade Budenz." (9) At this meeting she only gave the names of Jacob Golos and Earl Browder as spies.

Another meeting was held on the 7th November 1945. This time she the FBI a 107 page statement that named William Remington, Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Ludwig Ullman, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Cedric Belfrage and Lauchlin Currie as Soviet spies. The following day J. Edgar Hoover, sent a message to Harry S. Truman confirming that an espionage ring was operating in the United States government. (10) Some of these people, including White, Currie, Bachrach, Witt and Wadleigh, were named by Whittaker Chambers in 1939. (11)

There is no doubt that the FBI was taking her information very seriously. As G. Edward White, has pointed out: "Among her networks were two in the Washington area: one centered in the War Production Board, the other in the Treasury Department. The networks included two of the most highly placed Soviet agents in the government, Harry Dexter White in Treasury and Laughlin Currie, an administrative assistant in the White House." (12) Amy W. Knight, the author of How the Cold War Began: The Ignor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies (2005) has suggested that it had added significance because it followed the defection of Ignor Gouzenko. (13)

On 15th April, 1947, the FBI descended on the homes and businesses of twelve of the names provided by Bentley. Their properties were searched and they were interrogated by agents over several weeks. However, all of them refused to confess to their crimes. J. Edgar Hoover was eventually advised that the evidence provided by Elizabeth Bentley, Louis Budenz, Whittaker Chambers and Hede Massing was not enough to get convictions. Hoover's main concern now was to protect himself from charges that he had bungled the investigation. (14)

On 30th July 1948, Elizabeth Bentley appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. The senators were relatively retrained in their questioning. They asked Bentley to mention only two names in public: William Remington and Mary Price. Apparently the reason for this was that Remington and Price had both been involved in Henry A. Wallace campaign. Bentley was also reluctant to give evidence against these people and made it clear that she was not sure if Remington knew his information was going to the Soviet Union. She also described spies such as Remington and Price as "misguided idealists". (15)

The following day Bentley named several people she believed had been Soviet spies while working for the United States government. This included Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Harold Glasser, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Charles Kramer and Lauchlin Currie. One of the members of the HUAC, John Rankin, and well-known racist, pointed out the Jewish origins of these agents. (16) Silverman, Kramer, Collins and Witt all used the Fifth Amendment defence and refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC. (17)

William Remington agreed to answer questions before Congressional committees. Athan Theoharis, the author of Chasing Spies (2002), believes this was a serious mistake: "Remington's problems stemmed from two factors. First, he did not take the Fifth Amendment when responding to the committee's questions in striking contrast, for example, to Silvermaster and Perlo. Second, by then most of the individuals named by Bentley were no longer federal employees while Remington continued to hold a sensitive appointment in the Commerce Department. He was one of only three named by Bentley who was currently employed in the federal government." (18)

William Remington appeared before the Homer Ferguson Senate Committee. He admitted meeting Elizabeth Bentley but denied he helped her to spy. He claimed that Bentley had presented herself as a reporter for a liberal periodical. They had discussed the Second World War on about ten occasions but had never given her classified information. The committee did not find Remington's explanation persuasive, and neither did the regional loyalty board. The board soon recommended his dismissal from the government. (19)

Elizabeth Bentley appeared before the NBC Radio's Meet the Press. One of the reporters asked her if William Remington was a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA)? She replied: "Certainly... I testified before the committee that William Remington was a communist." To preserve his credibility Remington sued both NBC and Bentley. On 15th December, 1948, Remington's lawyers served her with the libel papers. The libel suit was settled out of court shortly thereafter, with NBC paying Remington $10,000. (20)

John Gilland Brunini, the foreman of the new grand jury investigating the charges made by Elizabeth Bentley, insisted that Ann Remington, who had divorced her husband, should appear before them. During interrogation by Bentley's lawyer, Thomas J. Donegan, Ann Remington admitted that William Remington was a member of the CPUSA and that he had provided Bentley with secret government documents. "Ann Remington was the first person from Elizabeth's espionage days who did not portray her as a fantasist and a psychopath." (21) On 18th May, 1950, Elizabeth Bentley testified before the grand jury that Remington was a communist. When he stopped spying we "hated to let him go." The grand jury now decided to indict Remington for committing perjury. (22)

William Remington's Trial

William Remington's trial began on 26th December 1950. Irving Saypol led the prosecution team. In his opening speech he argued: "We will prove that William W. Remington was a member of the Communist Parry, and we will prove that he lied when he denied it.... We will show his Communist Party membership from the mouths of witnesses who will take the stand before you, and from written documents which are immutable.... You will see... how, while drawing a high salary from the Government, he prostituted his position of trust... for the benefit of his Communist Party to which he was attached. For that Party we will show that he took documents and vital information from the War Production Board and turned these over to a fellow member of the Communist Party, for ultimate delivery to Russia. It will he shown ... that his adherence and his loyalty was primarily to the Russian Government.... I am confident that on the basis of the overwhelming and undisputed evidence which is about to he presented to you, you will find beyond any reasonable doubt that Remington lied to the grand jury, that he is guilty of... perjury." (23)

Roy Cohn, was a member of the prosecuting team. He pointed out that the main witness against William Remington was his former wife, Ann Remington. She explained that her husband had joined the Communist Party of the United States in 1937. Ann also testified that he had been in contact with both Elizabeth Bentley and Jacob Golos. "Elizabeth Bentley later supplied a wealth of detail about Remington's involvement with her and the espionage conspiracy. Remington's defense was that he had never handled any classified material, hence could not have given any to Miss Bentley. But she remembered all the facts about the rubber-from-garbage invention. We had searched through the archives and discovered the files on the process. We also found the aircraft schedules, which were set up exactly as she said, and inter office memos and tables of personnel which proved Remington had access to both these items. We also discovered Remington's application for a naval commission in which he specifically pointed out that he was, in his present position with the Commerce Department, entrusted with secret military information involving airplanes, armaments, radar, and the Manhattan Project (the atomic bomb)." (24)

One of Remington's main witnesses was Bernard Redmont. During cross-examination Irving Saypol attempted to show that Redmont was a secret member of the Communist Party of the United States. Saypol asked him why he had changed his name from Rothenberg to Redmont. He explained that it was because "there is a certain amount of anti-Semitism in the world, unfortunately." Saypol (whose real name was Ike Sapolsky) replied "I take it you are of the Hebrew heritage?... So you wanted to conceal that by taking this other name... That is your concept of good Americanism?... As a matter of fact, it is the Communists who take the false names, isn't it?"

Saypol then went onto question Redmont about the name of his eight-year-old son, Dennis Foster Redmont. Saypol suggested that he had been named after two senior members of the CPUSA: William Z. Foster and Eugene Dennis. Redmont replied: "We named him Dennis because we liked the name. We named him Foster after... my grandfather." Saypol then suggested: "Didn't you tell some members of the Communist Party in Washington, D.C that you named your son Dennis Foster in honor of these dignitaries... of the Communist Parry?" "I certainly did not," Redmont insisted. (25)

During the trial eleven witnesses claimed they knew Remington was a communist. This included Elizabeth Bentley, Ann Remington, Professor Howard Bridgeman of Tufts University, Kenneth McConnell, an Communist organizer in Knoxville, Rudolph Bertram and Christine Benson, who worked with him at the Tennessee Valley Authority and Paul Crouch who provided him with copies of the southern edition of the communist newspaper, the Daily Worker. (26)

Remington was convicted after a seven-week trial. Judge Gregory E. Noonan handed down a sentence of five years - the maximum for perjury - noting that Remington's act of perjury had involved disloyalty to his country. One newspaper reported: "William W. Remington now joins the odiferous list of young Communist punks who wormed their way upward in the Government under the New Deal. He was sentenced to five years in prison, and he should serve every minute of it. In Russia, he would have been shot without trial." (27)

Thomas W. Swan, was highly critical of Saypol's behaviour during Remington's trial. He was especially unhappy with his cross-examination of Bernard Redmont: "We wish to admonish counsel for the prosecution that in case of a re-trial there should he no repetition of the cross-examination attack on defense witness Redmont.... Redmont testified that he had changed his name for professional reasons and that he had done so pursuant to Court order. On cross-examination the prosecutor continued his inquiry of this matter long after it became clear that the change of name had no relevancy to any issue at the trial, and could only serve to arouse possible racial prejudice on the part of the jury." (28)

The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the perjury conviction on the ground that Judge Noonan's charge to the jury had been "too vague and indefinite" in defining exactly what constituted party "membership." The court, which did not touch upon the guilt or innocence of the defendant, ordered a new trial to be held. Roy Cohn was convinced that this time they would be successful as he believed the evidence was overwhelming: "He had denied turning over secret information to Elizabeth Bentley - yet she had testified that he gave documents to her and we had produced copies of some of the documents. He had denied that he had attended Communist party meetings in Knoxville - yet witness after witness, all former Communists, had come forth to swear that Remington had attended the meetings. He had denied that he had paid dues to the Communist party - yet both Miss Bentley and his own former wife had said that he did. He had denied that he had asked anyone to join the party - yet his former boss at the TVA had testified Remington had asked him. He had denied even knowing about the existence of the Young Communist League at Dartmouth while he was an undergraduate - yet a classmate had said they had discussed the organization when they were students." (29)

Elizabeth Bentley was drinking heavily during this period and her lover during this period, Harvey Matusow, was worried about the impression she would make in court. He claimed that she was upset at her "frivolous treatment" in the press. "She didn't understand the hostility... She never got to the point where she could handle it." Bentley complained about the way she had been treated by the FBI: "She felt that she'd been used and abused." (30) Bentley told her friend, Ruth Matthews that she "should step out in front of a car and settle everything." (31)

However, according to Kathryn S. Olmsted, the author of Red Spy Queen (2002), she was a very good witness. "Once again, though, despite her emotional problems outside of court, Elizabeth performed well on the stand. As usual, she was somewhat snappish and impatient under cross-examination... But like his predecessors, Jack Minton (Remington's new attorney) could not shake her self-confidence. She again succeeded in creating the illusion of a calm, controlled, and even patronizing witness, a Sunday school teacher somehow dropped into the middle of an espionage trial." (32)

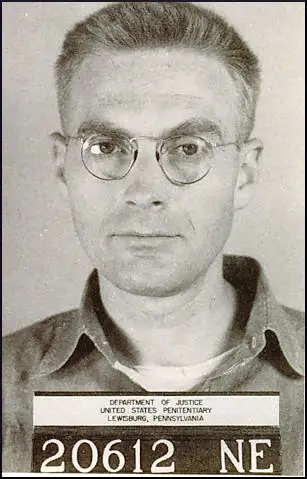

On 4th February, 1953, William Remington was sentenced to a three-year term. The Court of Appeals upheld the conviction, the Supreme Court denied Remington's application to be heard, and he was sent to Lewisburg Penitentiary. (33) The FBI was pleased by Elizabeth Bentley's testimony and pointed out that she had "conducted herself in a creditable fashion" and recommended continuing her weekly payments for another three months. J. Edgar Hoover approved the recommendation. (34)

Lewisburg Penitentiary

On 22nd November, 1954, two of Remington's fellow inmates George McCoy and Lewis Cagle, Jr., attacked Remington in his cell. According to Kathryn S. Olmsted: "William Remington attracted the attention of a group of young thugs in the cell across the hall. They despised this young man of education and privilege who had inexplicably turned on his country and become a 'damn Communist' and a 'traitor.' One morning, as Remington slept, they crept into his room and slugged him repeatedly with a brickbat. The handsome Ivy Leaguer died two days later. He was thirty-seven years old." (35)

People writing about the case have disagreed about the motivation of McCoy and Cagle. Roy Cohn, in his book, McCarthy (1968) argues that "Three fellow convicts crept into Remington's cell while he was asleep and bludgeoned him with a brick wrapped in a stocking. Remington staggered out and collapsed at the foot of a stairs. He died sixteen hours later in the prison hospital. At first there was suspicion that Remington had been murdered for his political views. Later it was disclosed that there had been other motives. It was a tragic end to what might have been a brilliant career." (36)

However, Gary May, the author of Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) believes that the killers were motivated by anti-Communism. He points out that one of the prison warders told Remington's wife that "the actions of a couple of hoodlums who got all worked up by... the publicity about Communists." May points out that when McCoy confessed he said he hated Remington for being a Communist and denied any robbery motive. (37)

Max Lerner, who knew Remington, wrote in the New York Post: "William Remington died as he lived, in dubious and ambiguous battle. He was a man who teetered on the edge of ideas, never a whole-hearted partisan of any cause.... He lived a life of bewildering mirror images. But while he was not a man to he admired, he did not deserve the vindictive pursuit he suffered, nor the hatreds he engendered among the unthinking and hysterical. Least of all did he deserve the brick in the sock wielded by two thugs who broke his skull in his prison cell." Murray Kempton added that Remington "was the least fortunate of men... the small sinner who paid capital penalties." (38)

Primary Sources

(1) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968)

He held degrees from two Ivy League colleges and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa. His father had been an executive in a large corporation, his mother an art teacher. He married the daughter of a banker. He was handsome, brilliant, and a Government economist. He accompanied and advised our top economic missions. He held high office in the Department of Commerce. Nobody would have suspected William Walter Remington of being a spy for the Communists.

And yet Remington, during the years that he held important positions with the United States Government, supplied valuable classified information to a Soviet courier for transmission to Moscow. He was finally convicted of perjury in denying certain incidents involving his Communist associations.

Remington was born in New York City in 1917 and spent his childhood in Ridgewood, New Jersey, an upper-middle-income community with neatly shrubbed homes and tree-shaded streets about twenty-five miles from Manhattan. At the age of sixteen he enrolled at Dartmouth College, where he immediately established himself as an outstanding student. In fact, he showed such unusual promise that he was one of only seven young scholars permitted to study independently in his senior year instead of having to follow a prescribed course.

It was also while at Dartmouth that William Remington joined the Young Communist League, which was the official youth movement of the Communist party and which in the thirties and forties had many active chapters in colleges throughout the nation. Each YCL cell was headed by a full party functionary and students were frequently recruited by a member of the faculty. The turnover in the organization was large-many young people joined and then left rather rapidly when the purpose of the organization became clear to them. However, a number went on to become full-fledged party members, and many important American Communists received their basic indoctrination in the YCL.

In 1936, when he was nineteen, Remington took a summer job with the Tennessee Valley Authority in Knoxville, Tennessee. There he met Kenneth McConnell, a Communist functionary on an inspection trip of the party's apparatus in the area. Remington became a full party member and during the summer of 1936 went with McConnell to recruitment centers where he helped win new members for the party. He even approached one of his superiors, Rudolph Bertram; the plea was not successful.

The summer over, Remington returned to Dartmouth and shortly afterward met a Radcliffe girl named Ann Moos. Ann was a Communist with a banker father who lived at Croton-on-Hudson in Westchester County, New York. Before she agreed to wed William Remington she exacted a promise from him that he would continue to support the cause. It was a case of "love me, love my party." They were married in 1939 and settled down shortly thereafter at the Moos home in Croton. Remington worked for a master's degree in economics at Columbia University and attended courses in Marxist economics at the Worker's School. He stayed in constant contact with Joseph North, editor of the Communist New Masses and the man who had recommended the field of economics to Remington.

Next Remington got a job in the Department of Commerce under Thomas C. Blaisdell, a New Deal economist, who held many high posts including that of Assistant Secretary of Commerce and chief of the Mission of Economic affairs. When Blaisdell became assistant to the director of the War Production Board, he asked Remington to join him at a higher salary. Remington accepted the offer and arranged to meet Joe North in Washington to discuss how the party could take advantage of his new position.

Remington applied for a commission in the Navy in April, 1944, and got it quickly. Later, Blaisdell asked for him to come to London on a special economic mission, where he remained a short time. In 1947, Blaisdell went to the Department of Commerce as director of the Office of International Trade, and took Remington with him in a ten-thousand-dollar-a-year post. In the Department of Commerce in 1948, Remington had an ideal position for a Communist spy: presiding over a committee with final control over the issuance of licenses for the export of goods to Iron Curtain countries.

The FBI had Remington under watch and sent confidential reports to his superiors, warning that he had been named a Communist spy by a reliable informant. The FBI had questioned him and he had admitted acquaintance with Golos and Bentley. However, Blaisdell ignored the FBI reports. He did confide with one person about what the FBI knew concerning Remington's activities and that was Remington himself. Remington assured Blaisdell that he was not a Communist spy. There the matter was closed - and Remington kept his job, passing on export licenses to Russia's satellites. The FBI could do nothing further about Remington since its jurisdiction was limited to passing along reports to agency chiefs.

After Elizabeth Bentley repeated her accusations against him without immunity on the National Broadcasting Company radio program "Meet the Press," Remington instituted a suit for $100,000. When Miss Bentley refused to retract her statements, NBC and the program's sponsor, General Foods Corporation, made an out-of-court settlement for $10,000. It appeared as though Remington's vindication was indeed complete.

(2) Athan Theoharis, Chasing Spies (2002)

The politicization of the grand jury process to ensure Hiss's indictment (owing once again to the FBI's inability to develop admissible evidence of espionage activities) was replicated in the case of William Remington. The foreman of the grand jury that returned Remington's indictment, John Brunini; U.S. attorney Thomas Donegan; and senior Justice Department officials combined to politicize the grand jury process and thereby secure Remington's perjury conviction.

Remington's travails had their origins in Elizabeth Bentley's defection in November 1945, when she informed FBI agents of her role as a courier for a wartime Soviet espionage ring, then identified the Communist federal employees who comprised it. Bentley eventually named 150 individuals during her FBI interviews. Nathan Silvermaster and Victor Perlo, she claimed, had headed two separate espionage operations. Remington did not figure prominently in Bentley's original account of Soviet espionage.

An intensive FBI investigation was launched to corroborate Bentley's account, during which FBI agents broke into Remington's residence, intercepted his mail, and tapped his phone despite his peripheral status in Bentley's account. As in the cases of the others named by Bentley, FBI agents could not develop any admissible evidence to indict Remington for espionage. Nonetheless the Justice Department convened a federal grand jury in 1948, hoping to pressure one or more of the subpoenaed witnesses into admitting their role and implicating others. Remington was among those subpoenaed. In his grand jury testimony he was questioned about his relationship with Bentley and specifically whether he had been a member of the Communist party or had paid party dues. He was not indicted by this grand jury - nor, for that matter, were any of the others named by Bentley.

When no indictments were returned, two congressional committees initiated public hearings in the summer of 1948, one focusing on Bentley's testimony and the other on that of Whittaker Chambers. These hearings proved damaging to both Remington's and Hiss's reputations. Remington's problems stemmed from two factors. First, he did not take the Fifth Amendment when responding to the committee's questions in striking contrast, for example, to Silvermaster and Perlo. Second, by then most of the individuals named by Bentley were no longer federal employees while Remington continued to hold a sensitive appointment in the Commerce Department. He was one of only three named by Bentley who was currently employed in the federal government.

In her July 27, 1948, testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Expenditures in Government, Bentley accused Remington only of having paid his Communist party dues to her and of having given her secret information on aircraft production in the belief that this information was to be given to Earl Browder, executive secretary of the American Communist parry. Remington did not know, Bentley explained, that this information was delivered to the Soviet Union. Subpoenaed to testify before the Senate subcommittee, Remington admitted having met Bentley in Washington during the war years, to having thought she was a freelance journalist for leftist publications, and to having given her only public information about war production in order to rebut Communist and radical suspicions that they U.S. government was "an appeasement government but instead was going to fight the war and win."

(3) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002)

When Elizabeth protested that "she needed income immediately and further knew nothing about writing," Brunini explained that she could get an advance with an outline and a sample chapter. As it happened, he was publishing a book that year with Devin A. Garrity, owner of the Devin-Adair publishing house. He would be happy to help her find a publisher and put together a proposal." Thus Elizabeth set out to write a book with the foreman of the grand jury still investigating her allegations.

As her unofficial literary agent, editor, and mentor, Brunini had an interest in boosting Elizabeth's credibility and raising her public profile. He received some valuable intelligence that would help him in this quest in late April. At a dinner with reporters, he learned that the FBI had found evidence that Remington had committed perjury when he denied Party membership under oath. The bureau planned to present this evidence to a congressional committee and a Washington grand jury-not to Brunini's jury. Deeply angered, the foreman spent a "sleepless night" before resolving to urge his jurors to demand the right to question Remington." If successful, this inquiry could reveal the flaws in Truman's loyalty program and, not incidentally, restore his coauthor's credibility. As Gary May has concluded, "Political extremism and personal gain led Brunini to choose action."

Brunini was the guiding force behind the Remington perjury investigation: he researched the evidence and suggested witnesses. His major discovery was that the FBI had failed to question Ann Remington, who was now Bill's ex-wife. The foreman demanded that the prosecutors subpoena her." Under intense pressure from Brunini and prosecutor Tom Donegan, Ann Remington finally broke down and admitted that her husband had paid Party dues to Bentley and passed her some information."

Here, at last, was the "weak sister" who could corroborate Elizabeth's charges. Ann Remington was the first person from Elizabeth's espionage days who did not portray her as a fantasist and a psychopath.

Elizabeth relished the opportunity to exact revenge from the man who had falsely denied her charges and investigated her personal life. On May 18, she testified about Remington before Brunini's grand jury - and did her best to ensure his indictment. The most notable change in her testimony concerned Remington's knowledge of the ultimate destination of his information. Just two weeks earlier, in new testimony before HUAC, she had called Remington a "minor figure" in her espionage activities and explained that he "thought the information was going to the American Communist Party." When he had stopped spying, she had said, "it wasn't too great a loss to us."" Before the grand jury, though, she transformed Remington into an important, knowing NKGB agent. Because of his value, Elizabeth and the Soviets had "hated to let him go."

On June 8, Brunini's grand jury indicted Remington for perjury. It was the first indictment based on Elizabeth's allegations.

(4) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968)

Remington's trial opened early in January, 1951. Chanler's opening to the jury was, in effect, an attack on Elizabeth Bentley. Then, shortly before adjournment on the first day, Irving Saypol announced his first witness and a slender brunette stepped forward. She was not, as everyone expected, Elizabeth Bentley, but Remington's divorced wife, Ann. A look of acute puzzlement spread across the face of Defense Counsel Chanler, who had obviously built most of his defense on discrediting Miss Bentley.

Quietly, tersely, Ann Remington told of her early acquaintance with Remington, whom she said she had known since 1937 when she was a student at Radcliffe. She told of a conversation they had had one evening as they sat parked in her car near a Dartmouth dormitory. "He told me he was a member of the Communist party," she testified, "and abjured me to secrecy on that." In 1938, she said, Remington told her he was dropping out of the Young Communist League. "It was more expedient and he could do more good outside," she testified. About her marriage, she said, "One of the requirements I asked was that he would continue to be a Communist. He said I need not worry on that score." She testified that during the time they lived in New York, they distributed Communist literature door-to-door. On their move to Washington, she said, Remington felt "out of touch" with the party, so he had Joe North introduce him to "John" - Jacob Golos.

Elizabeth Bentley later supplied a wealth of detail about Remington's involvement with her and the espionage conspiracy. Remington's defense was that he had never handled any classified material, hence could not have given any to Miss Bentley. But she remembered all the facts about the rubber-from-garbage invention. We had searched through the archives and discovered the files on the process. We also found the aircraft schedules, which were set up exactly as she said, and interoffice memos and tables of personnel which proved Remington had access to both these items.

We also discovered Remington's application for a naval commission in which he specifically pointed out that he was, in his present position with the Commerce Department, entrusted with secret military information involving airplanes, armaments, radar, and the Manhattan Project (the atomic bomb).

While Paul Crouch, a former Communist functionary, was checking reports that Remington had subscribed to a newspaper called the Southern Worker, which was the southern edition of the Daily Worker, he came upon something a good deal more significant. The Knoxville post-office box at which he received the Worker was the official box of the Communist party, and only trusted Communist party members were allowed to use it.

Crouch was called to the stand as a surprise witness. It was a dramatic afternoon. His son was dying in Miami, and we obtained special permission to have him called out of order. Chanler, visibly shaken when Crouch produced the Remington subscription card and told about the post-office box, asked to examine all the other cards that Crouch had in the shoe box-with a view toward showing that non-Communists as well as Communists subscribed to the Worker. Chanler passed the box to his staff of assistants sitting alongside him at the counsel table... All together, the prosecution produced eleven witnesses, most of them former Communists, who testified they had known Remington as a political collaborator. In addition to McConnell, Miss Bentley, and Mrs. Remington, the witnesses included Rudolph Bertram, former TVA personnel director, who swore Remington had tried to get him to join the party; and Professor Howard Bridgeman of Tufts University and Christine Benson, a former TVA employee, who testified they had attended party meetings with Remington in Knoxville.

Remington's defense was based upon the claim that although he had had a casual flirtation with left-wing causes in his youthful years, he had never taken the step of joining the Communist party nor had he ever passed any of his country's secrets to anybody. His parents and a number of character witnesses appeared in his behalf. Remington himself took the stand, testifying that his college reputation as a Communist stemmed from joking references he made to himself as a "bolshevik." He insisted that he had never gone to any Communist party meetings in Knoxville, that he had never paid any dues to the party, and that he had not known Elizabeth Bentley as a Communist spy but as a newspaper reporter.

The testimony was predictable and answerable. For me, the most exciting moment in the trial came toward its close during the defense presentation. We learned that the defense was planning to produce a witness next day whom we knew only by his last name, Martin. There were two possibilities, since there were two Martin brothers who were in Knoxville with Remington. One was David Stone Martin, the other Francis Martin. I asked the FBI and our own investigators to obtain all the official records they could get their hands on about the two Martins, including personnel files. It was and is my practice to know as much about the cast of players as is possible.

Late that night, the last file arrived from Washington. An FBI agent looked through it and came over to me to report. He said that David Martin had been questioned under the Civil Service loyalty program about his activities in Knoxville years before. I asked if there was anything significant in his answers. The agent, with a straight face, said there was one answer I might want to see. I picked up the file and read the page he cited. I stared almost unbelievingly.

In the course of an answer in his loyalty quiz, David Martin had sworn in 1943 that while in Knoxville he had not known many Communists-"except Bill Remington. He was one of the townspeople and everyone knew him as a character. He was a young fellow who was fanatical in his political beliefs. I won't deny that he was a Communist, as that was well known, because he approached everyone and asked them to join the Communist party."This from the lips of a defense witness called by Remington. It would be a hell of a cross-examination!

Next day, Attorney Chanler called David Stone Martin as his first witness. Apparently all that Chanler had wanted to establish through him was that there was a sort of hot-rod atmosphere in Knoxville at the time, and that Remington was part of it. Direct examination was soon complete.

We had Irving Saypol all primed for cross. He asked some routine questions. Then he had Martin say that he always told the truth. If he had made statements to the Civil Service Commission years before - which he did not now recall - of course they would be the truth. He was then shown his interrogatories of 1943, which he recognized. We then read certain inconsequential ones to him. As to each answer, he impatiently asserted it was the truth - all his answers were the truth.

At this point, Saypol, smiling, walked toward the witness chair. Those in the courtroom knew that something was up, for Irving was not known for his warm treatment of defense witnesses. As defense witness Martin's own words, naming the man for whom he was testifying as an active Communist, rang through the courtroom, I knew that we had scored a devastating point. Later, while deliberating, the jury asked for a copy of this 1943 statement by Martin.

The jury was out a short time. It received the case in the late afternoon and by 10 P.M., Judge Noonan received a note that the jury had agreed upon a verdict. The foreman stood and said, "We find the defendant guilty as charged."

(5) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) 193

Elizabeth's emotional health was always fragile, though, and any stress could bring out her paranoia, her depression, and her tremendous thirst. Over the next academic year at Sacred Heart, the stresses multiplied along with the rum and whiskey bottles in her trash.

The first blow came in November 1954. At Lewisburg Penitentiary in Pennsylvania, William Remington attracted the attention of a group of young thugs in the cell across the hall. They despised this young man of education and privilege who had inexplicably turned on his country and become a "damn Communist" and a "traitor." One morning, as Remington slept, they crept into his room and slugged him repeatedly with a brickbat. The handsome Ivy Leaguer died two days later. He was thirty-seven years old.

Elizabeth had suffered from nightmares about betraying her friends. Now, she was indirectly responsible for one friend's death. There is no record, though, of her precise reaction. When reporters called, she refused to comment.

(6) Max Lerner, New York Post (26th November, 1954)

William Remington died as he lived, in dubious and ambiguous battle. He was a man who teetered on the edge of ideas, never a whole-hearted partisan of any cause.... He lived a life of bewildering mirror images. But while he was not a man to he admired, he did not deserve the vindictive pursuit he suffered, nor the hatreds he engendered among the unthinking and hysterical. Least of all did he deserve the brick in the sock wielded by two thugs who broke his skull in his prison cell.

(7) Carey McWilliams, The Nation (28th December, 1957)

There are some issues that never die until society makes amends for the injustice done... Alger Hiss may yet he vindicated but Remington, whose violent and tragic death... was the result of the malice, prejudice and ambitions of cheap political opportunists, is beyond any meaningful vindication. Remington remains as a permanent, an irrevocable burden on the American conscience.

References

(1) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 31

(2) Gary May, Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) page 21

(3) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 32

(4) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) pages 53-54

(5) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 46

(6) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 33

(7) Silvermaster FBI File 65-56402-3414

(8) New York Times (11th October, 1945)

(9) Allen Weinstein, The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) page 105

(10) Edgar Hoover, memo to President Harry S. Truman (8th November 1945)

(11) Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952) page 464

(12) G. Edward White, Alger Hiss's Looking-Glass Wars (2004) page 48

(13) Amy W. Knight, How the Cold War Began: The Ignor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies (2005) 89-90

(14) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) pages 117-124

(15) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 130

(16) House of Un-American Activities Committee (31st July, 1948)

(17) Sam Tanenhaus, Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) page 246

(18) Athan Theoharis, Chasing Spies (2002) pages 132

(19) Gary May, Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) page 119

(20) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 148

(21) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 158

(22) Gary May, Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) page 167

(23) Irving Saypol, speech in court at the William Remington trial (26th December, 1950)

(24) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 38

(25) Gary May, Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) 238-239

(26) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) pages 39-40

(27) Washington Daily News (February, 1951)

(28) Thomas W. Swan, court opinion of the William Remington trial (22nd August, 1951)

(29) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 42

(30) Harvey Matusow, phone interview with Kathryn S. Olmsted (11th July, 2001)

(31) Elizabeth Bentley FBI File 134-182-66

(32) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 184

(33) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 43

(34) J. Edgar Hoover, memo to New York office (5th February, 1953)

(35) Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen (2002) page 184

(36) Roy Cohn, McCarthy (1968) page 43

(37) Gary May, Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington (1994) pages 314-321

(36) Max Lerner, New York Post (26th November, 1954)