Emperor Hirohito

Hirohito, the grandson of Emperor Meiji, was born in Japan on 29th April 1901. His father, Emperor Taisho, came to power in 1912.

In 1915 Hirohito was tutored by Kimmochi Saionju, the former prime minister of Japan. As a young man he became very interested natural science and marine biology. When Hirohito visited Europe in 1921 he became the first Japanese prince to travel to the west. He spent some time in Britain and had meetings with George V.

Hirohito became emperor on the death of his father in December 1926. He therefore became the 124th emperor in direct lineage.

Under the constitution of Japan the Emperor could not act except on the advice of his ministers and the chiefs of staff. However, when a group of officers in the Japanese Army led a military coup against the political leaders in February, 1936, Hirohito ordered his senior advisers, against their wishes, to put the rebellion down. As a result of Hirohito's action, the ringleaders were executed.

Hirohito reluctantly supported the war against China (1931-32) and the invasion of Manchuria in 1937. However, he approved the attack on Pearl Harbor that led to Japan and the United States being drawn into the Second World War.

When the promised quick victory over the Allies did not take place, Hirohito became critical of the political leaders and this led to the removal of Hideki Tojo on 18th July 1944. After the loss of Okinawa Hirohito called on his ministers to seek a negotiated end to the conflict. However, his government refused, claiming that Japan and Germany could still win the war.

After atom bomb were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki Hirohito called a meeting of the Supreme Council on 9th August, 1945. After a long debate Hirohito intervened and said he could no longer bear to see his people suffer in this way. On 15th August the people of Japan heard the Emperor's voice for the first time when he announced the unconditional surrender and the end of the war. Naruhiko Higashikuni was appointed as head of the surrender government.

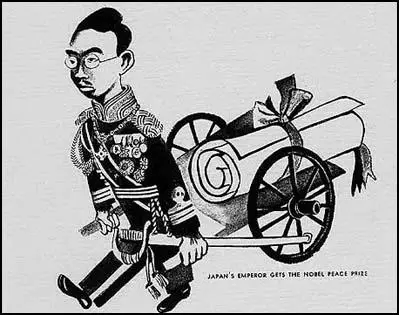

Some Allied leaders wanted Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal but General Douglas MacArthur head of the occupation forces, refused, arguing that Japan would be easier to rule if the emperor remained in office.

The American-imposed Japanese constitution reduced the emperor to a ceremonial role. On 1st January 1946, Hirohito made a formal statement where he explained that the role of the emperor in Japan had changed. He explained that the ties between himself and the Japanese people had always involved "mutual trust and affection". He went on to say: "They do not depend upon mere legends and myths. They are not predicated on the false conception that the Emperor is divine and that the Japanese people are superior to other races."

Other reforms introduced by General Douglas MacArthur encouraged the creation of democratic institutions, religious freedom, civil liberties, land reform, emancipation of women and the formation of trade unions.

After the war Hirohito retained the affection of the Japanese people and showed that the Japanese monarchy was indeed modernized when he gave permission for Crown Prince Akihito to marry a commoner. Hirohito, who was a notable marine biologist, died after a long illness on 7th January, 1989.

Primary Sources

(1) In his memoirs Cordell Hull wrote about negotiations that took place between the United States and Japan just before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

The President now had before him two draft messages, which I had sent him during his absence. One was a message to Congress, which Secretaries Stimson and Knox had helped me prepare, advising it of the imminent dangers in the situation. The other was a message to Emperor Hirohito of Japan, appealing for peace.

This second message had been under discussion since October among those of us concerned with the Far East. In my memorandum to the President accompanying these drafts, I suggested: "If you should send this message to the Emperor it would be advisable to defer your message to Congress until we see whether the message to the Emperor effects any improvement in the situation. I think we agree that you will not send the message to Congress until the last stage of our relations, relating to actual hostility, has been reached."

I had two reasons for this last comment. One was that the message to Congress could contain very little that was new without giving the Japanese leaders material with which to arouse their people against us all the more. The other was that the powerful isolationist groups still existing in Congress and in the United States might use it to renew their oft repeated charges of "warmongering" and "dragging the nation into foreign wars." The Japanese military could then have played up the situation as evidencing disunity in the United States, thus encouraging the Japanese to support their plans for plunging ahead into war.

I also was not in favor of the message to the Emperor, except as a last-minute resort, and I so informed the President. I felt that the Emperor, in any event, was a figurehead under the control of the military Cabinet. A message direct to him would cause Tojo's Cabinet to feel that they were being short-circuited and would anger them. Besides, I knew that the Japanese themselves did not make use of such means as a direct Presidential message. Normally they did not shift from a bold front to one of pleading until the situation with them was desperate. They would therefore regard the message as our last recourse and a sign of weakness.

(2) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (20th December 1941)

The Japanese successes are still very serious for us. At present the pressure of Japanese troops has died down in Malaya, where heavy casualties have been inflicted upon them. Large Indian reinforcements have been landed in Rangoon. The Governor of Hong Kong states that heavy fighting is in progress, on the island itself.

In all this we must remember that the Japanese power, though great, can only aim at a rapid outright victory. The three Axis powers together can produce 60 million tons of steel every year, whereas the USA alone can produce about 88 million. This in itself is not a striking difference. But Japan cannot send help to Germany, and Germany cannot send help to Japan. For the Japanese only produce 7 million tons of steel a year. For steel, as for many other things, they must depend on the stores they have ready.

If the Japanese seem to be making a wild attempt, we must remember that many of them think it their duty to their Emperor, who is their God, to conquer the whole world. This is not a new idea in Japan. Hideyoshi when he died in 1598 was trying to conquer the whole world known to him, and he knew about India and Persia. It was because he failed that Japan closed the country to all foreigners.

In January of this year, to take a recent example, a manifesto appeared in the Japanese press signed by Japanese Admirals and Generals stating that it was Japan's mission to set Burma and India free. Japan was of course to do this by conquering them. What it would be like to be free under the heel of Japan the Chinese can tell us, and the Koreans.

(3) Emperor Hirohito, radio broadcast (1st January, 1946).

They do not depend upon mere legends and myths. They are not predicated on the false conception that the Emperor is divine and that the Japanese people are superior to other races.

(4) In his memoirs General Douglas MacArthur wrote about his first meeting with Emperor Hirohito after the end of the Second World War.

Shortly after my arrival in Tokyo, I was urged by members of my staff to summon the Emperor to my headquarters as a show of power. I brushed the suggestions aside. "To do so," I explained, "would be to outrage the feelings of the Japanese people and make a martyr of the Emperor in their eyes.

No, I shall wait and in time the Emperor will voluntarily come to see me. In this case, the patience of the East rather than the haste of the West will best serve our purpose."

The Emperor did indeed shortly request an interview. In cutaway, striped trousers, and top hat, riding in his Daimler with the imperial grand chamberlain facing him on the jump seat, Hirohito arrived at the embassy. I had, from the start of the occupation, directed that there should be no derogation in his treatment. Every honor due a sovereign was to be his. I met him cordially, and recalled that I had at one time been received by his father at the close of the Russo-Japanese War. He was nervous and the stress of the past months showed plainly. I dismissed everyone but his own interpreter, and we sat down before an open fire at one end of the long reception hall.

I offered him an American cigarette, which he took with thanks. I noticed how his hands shook as I lighted it for him. I tried to make it as easy for him as I could, but I knew how deep and dreadful must be his agony of humiliation. I had an uneasy feeling he might plead his own cause against indictment as a war criminal. There had been considerable outcry from some of the Allies, notably the Russians and the British, to include him in this category. Indeed, the initial list of those proposed by them was headed by the Emperor's name. Realizing the tragic consequences that would follow such an unjust action, I had stoutly resisted such efforts. When Washington seemed to be veering toward the British point of view, I had advised that I would need at least one million reinforcements should such action be taken. I believed that if the Emperor were indicted, and perhaps hanged, as a war criminal, military government would have to be instituted throughout all Japan, and guerrilla warfare would probably break out. The Emperor's name had then been stricken from the list. But of all this he knew nothing.

But my fears were groundless. What he said was this: "I come to you, General MacArthur, to offer myself to the judgment of the powers you represent as the one to bear sole responsibility for every political and military decision made and action taken by my people in the conduct of war." A tremendous impression swept me. This courageous assumption of a responsibility implicit with death, a responsibility clearly belied by facts of which I was fully aware, moved me to the very marrow of my bones. He was an - Emperor by inherent birth, but in that instant I knew I faced the First Gentleman of Japan in his own right.

(5) List of reforms that General Douglas MacArthur submitted to Emperor Hirohito and his Japanese government in October 1945.

1. The emancipation of the women of Japan through their enfranchisement - that, being members of the body politic, they may bring to Japan a new concept of government directly subservient to the well-being of the home.

2. The encouragement of the unionization of labor-that it may have an influential voice in safeguarding the working man from exploitation and abuse, and raising his living standard to a higher level.

3. The institution of such measures as may be necessary to correct the evils which exist in the child labor practices.

4. The opening of the schools to more liberal education-that the people may shape their future progress from factual knowledge and benefit from an understanding of a system under which government becomes the servant rather than the master of the people.

5. The abolition of systems which through secret inquisition and abuse have held the people in constant fear-substituting therefor a system of justice designed to afford the people protection against despotic, arbitrary and unjust methods. Freedom of thought, freedom of speech, freedom of religion must be maintained. Regimentation of the masses under the guise or claim of efficiency, under whatever name of government it may be made, must cease.

6. The democratization of Japanese economic institutions to the end that monopolistic industrial controls be revised through the development of methods which tend to insure a wide distribution of income and ownership of the means of production and trade.

7. In the immediate administrative field take vigorous and prompt action by the government with reference to housing, feeding and clothing the population in order to prevent pestilence, disease, starvation or other major social catastrophe. The coming winter will be critical and the only way to meet its difficulties is by

the full employment in useful work of everyone.

(6) Richard Storry, History Today (January, 1982)

The fact that he never moved into a safe area, such as his country villa, during the horrendous air raids on the capital endeared him to the citizens of Tokyo. His post-war appearances, in a seemingly shabby suit and crumpled hat with the rather dumpy, comfortable, smiling figure of the Empress by his side, aroused sympathy as well as respect. It was very different from the picture presented of the Emperor in uniform, very capable on his white horse (the Emperor happened to be an excellent rider), reviewing the Guards Division.