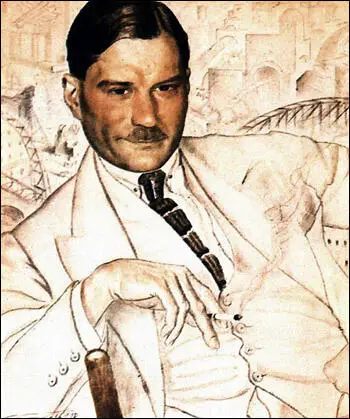

George Orwell

Eric Blair (George Orwell), the only son of Richard Walmesley Blair, and his wife, Ida Mabel Limouzin, was born in Bengal, India, on 25th June 1903. His sister, Marjorie, had been born in 1898. His father was a sub-deputy agent in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service. (1)

In the summer of 1907, Mabel Blair brought her son and daughter home to England and set up home in Henley-on-Thames. A third child, Avril, was born in 1908. In September, 1911, Orwell was sent to St Cyprian's, a private preparatory school at Eastbourne.

He later recalled: "I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays... I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life." (2)

In 1917 Orwell entered Eton College. Over the next four years he wrote satirical verses and short stories for various college magazines. He disapproved of his public school education and many years later he wrote: "Whatever may happen to the great public schools when our educational system is reorganised, it is almost impossible that Eton should survive in anything like its present form, because the training it offers was originally intended for a landowning aristocracy and had become an anachronism... The top hats and tail coats, the pack of beagles, the many-coloured blazers, the desks still notched with the names of Prime Ministers had charm and function so long as they represented the kind of elegance that everyone looked up to." (3)

When he left Eton in 1921 he did not go to university and instead joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. He hated the experience and during this period he became a socialist and an anti-imperialist: "This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism." (4)

Down and Out in Paris and London

In the autumn of 1927 George Orwell began living in a cheap room in Portobello Road, Notting Hill. He spent a great deal of his time in the East End of London in his quest to get to know the poor and exploited. In the spring of 1928 he moved to a working-class district of Paris. For about ten weeks in the late autumn of 1929 he worked as a dishwasher and kitchen porter in a luxury hotel and a restaurant in the city.

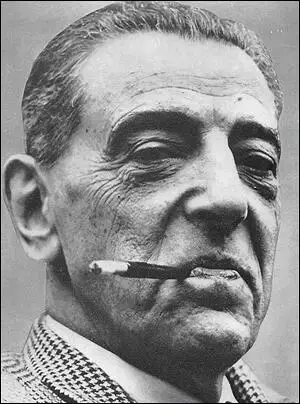

On his return to London he became friends with Kingsley Martin, John Middleton Murry and Richard Rees , who helped him to get articles and reviews published in journals such as the New Statesman, New English Weekly and The Adelphi. Orwell also became friends with the left-wing publisher, Victor Gollancz, and in 1933 he published Down and Out in Paris and London. (5)

Orwell wrote in the introduction to the book: "I have given the impression that I think Paris and London are unpleasant cities. This was never my intention and if, at first sight, the reader should get this impression this is simply because the subject-matter of my book is essentially unattractive: my theme is poverty. When you haven't a penny in your pocket you are forced to see any city or country in its least favourable light and all human beings, or nearly all, appear to you either as fellow sufferers or as enemies." (6)

However, Gollancz came under attack from some of his Jewish customers. S. M. Lipsey wrote: "As a Jew it is to me inexplicable that one of the most eminent and honourable names in Anglo-Jewry should bear the imprimatur of a publication wherein are references to Jews of a most contemptible and repugnant character. I feel bound to enter a very earnest and emphatic protest." Gollancz replied: "I detest all forms of patriotism, which has made, and is making, the world a hell: and of all forms of patriotism, Jewish patriotism seems to me the most detestable. If Down and Out in London and Paris has given a jar to your Jewish complacency, I have one additional reason to be pleased for having published it." (7)

George Orwell: Novelist and Journalist

Over the next few years he published three novels, Burmese Days (1934), A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) and Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). The books did not sell well and Orwell was unable to make enough money to become a full-time writer and had to work as a teacher and as an assistant in a bookshop.

Orwell had been shocked and dismayed by the persecution of socialists in Nazi Germany. Like most socialists, he had been impressed by the way that the Soviet Union had been unaffected by the Great Depression and did not suffer the unemployment that was being endured by the workers under capitalism. However, Orwell was a great believer in democracy and rejected the type of government imposed by Joseph Stalin.

Orwell decided he would now become a political writer "In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer... Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows." (8)

Orwell was commissioned by Victor Gollancz to produce a documentary account of unemployment in the north of England for his Left Book Club. In February, 1936, Orwell wrote to Richard Rees about his research for the book that was eventually published as the The Road to Wigan Pier. "I have only been down one coal mine so far but hope to go down some more in Yorkshire. It was for me a pretty devastating experience and it is fearful thought that the labour of crawling as far as the coal face (about a mile in this case but as much as 3 miles in some mines), which was enough to put my legs out of action for four days, is only the beginning and ending of a miner's day's work, and his real work comes in between." (9)

The Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War began on 18th July, 1936. Despite only being married for a month he immediately decided to go and support the Popular Front government against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. He contacted John Strachey who took him to see Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Orwell later recalled: "Pollitt after questioning me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me, also tried to frighten me out of going by talking a lot about Anarchist terrorism." (10)

Orwell visited the headquarters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and obtained letters of recommendation from Fenner Brockway and Henry Noel Brailsford. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, to run the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an anti-Stalinist organisation formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. As a result of an ILP fundraising campaign in England, the POUM had received almost £10,000, as well as an ambulance and a planeload of medical supplies. (11)

It has been pointed out by D. J. Taylor, that McNair was "initially wary of the tall ex-public school boy with the drawling upper-class accent". (12) McNair later recalled: "At first his accent repelled my Tyneside prejudices... He handed me his two letters, one from Fenner Brockway, the other from H.N. Brailsford, both personal friends of mine. I realised that my visitor was none other than George Orwell, two of whose books I had read and greatly admired." Orwell told McNair: "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism". Orwell told him that he was also interested in writing about the "situation and endeavour to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France." (13) Orwell talked about producing a couple of articles for The New Statesman. (14)

McNair went to see Orwell at the Lenin Barracks a few days later: "Gone was the drawling ex-Etonian, in his place was an ardent young man of action in complete control of the situation... George was forcing about fifty young, enthusiastic but undisciplined Catalonians to learn the rudiments of military drill. He made them run and jump, taught them to form threes, showed them how to use the only rifle available, an old Mauser, by taking it to pieces and explaining it." (15)

In January 1937 George Orwell, given the rank of corporal, was sent to join the offensive at Aragón. The following month he was moved to Huesca. Orwell wrote to Victor Gollancz about life in Spain. "Owing partly to an accident I joined the POUM miltia instead of the International Brigade which was a pity in one way because it meant that I have never seen the Madrid front; on the other hand it has brought me into contact with Spaniards rather than Englishmen and especially with genuine revolutionaries. I hope I shall get a chance to write the truth about what I have seen." (16)

A report appeared in a British newspaper of Orwell leading soldiers into battle: "A Spanish comrade rose and rushed forward. Charge! shouted Blair (Orwell)... In front of the parapet was Eric Blair's tall figure cooly strolling forward through the storm of fire. He leapt at the parapet, then stumbled. Hell, had they got him? No, he was over, closely followed by Gross of Hammersmith, Frankfort of Hackney and Bob Smillie, with the others right after them. The trench had been hastily evacuated... In a corner of a trench was one dead man; in a dugout was another body." (17)

On 10th May, 1937, Orwell was wounded by a Fascist sniper. He told Cyril Connolly "a bullet through the throat which of course ought to have killed me but has merely given me nervous pains in the right arm and robbed me of most of my voice." He added that while in Spain "I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before." (18)

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of POUM, National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI). Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." (19)

As Orwell had been fighting with POUM he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, George Orwell, John McNair and Stafford Cottman were able to escape to France on 23rd June. (20)

Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. When he arrived back in England he was determined to expose the crimes of Stalin in Spain. However, his left-wing friends in the media, rejected his articles, as they argued it would split and therefore weaken the resistance to fascism in Europe. Orwell was particularly upset by his old friend, Kingsley Martin, the editor of the country's leading socialist journal, The New Statesman, for refusing to publish details of the killing of the anarchists and socialists by the communists in Spain. (21)

Left-wing and liberal newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, as well as the right-wing Daily Mail and The Times, joined in the cover-up. Orwell did managed to persuade the New English Weekly to publish an article on the reporting of the Spanish Civil War. "I honestly doubt, in spite of all those hecatombs of nuns who have been raped and crucified before the eyes of Daily Mail reporters, whether it is the pro-Fascist newspapers that have done the most harm. It is the left-wing papers, the News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, with their far subtler methods of distortion, that have prevented the British public from grasping the real nature of the struggle." (22)

In another article in the magazine he explained how in "Spain... and to some extent in England, anyone professing revolutionary Socialism (i.e. professing the things the Communist Party professed until a few years ago) is under suspicion of being a Trotskyist in the pay of Franco or Hitler... in England, in spite of the intense interest the Spanish war has aroused, there are very few people who have heard of the enormous struggle that is going on behind the Government lines. Of course, this is no accident. There has been a quite deliberate conspiracy to prevent the Spanish situation from being understood." (23)

George Orwell wrote about his experiences of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia. The book was rejected by Victor Gollancz because of its attacks on Joseph Stalin. During this period Gollancz was accused of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). He later admitted that he had come under pressure from the CPGB not to publish certain books in the Left Book Club: "When I got letter after letter to this effect, I had to sit down and deny that I had withdrawn the book because I had been asked to do so by the CP - I had to concoct a cock and bull story... I hated and loathed doing this: I am made in such a way that this kind of falsehood destroys something inside me." (24)

The book was eventually published by Frederick Warburg, who was known to be both anti-fascist and anti-communist, which put him at loggerheads with many intellectuals of the time. The book was attacked by both the left and right-wing press. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years. As Bernard Crick has pointed out: "Its literary merits were hardly noticed... Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style." (25)

Stalinism and the British Left

Orwell was also appalled by the way the left-wing press had reported the trial of Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. It was claimed that they had plotted and carried out the assassination of Sergey Kirov and planned the overthrow of Joseph Stalin and his leading associates - all under the direct instructions of Leon Trotsky. They were also accused of conspiring with Adolf Hitler against the Soviet Union. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." (26) The New Statesman agreed that "very likely there was a plot" by the accused against Stalin. (27)

Orwell complained that the Daily Herald and the Manchester Guardian went along with this idea that there was this world-wide "Trotsky-Fascist" plot. He estimated that there were 3,000 political prisoners in Spanish prisons who were accused of being involved in this preposterous plot, but this was not being reported in the media. "The result was that there was no protest from abroad and all these thousands of people have stayed in prison, and a number have been murdered, the effect being to spread hatred and dissension all through the Socialist movement." (28)

Independent Labour Party

In 1938 Orwell was an isolated figure on the left. He rejected the policies of the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Labour Party. This was partly over the issue of Spain but saw Clement Attlee as a leader of a party that would probably "fling every principle overboard" in order to get power. He therefore joined the very small Independent Labour Party: "It is vitally necessary that there should be in existence some body of people who can be depended on, even in the face of persecution, not to compromise their Socialist principles." (29)

Orwell also supported rearmament in order to take on Adolf Hitler in the fight against fascism. In a range of different issues, from anti-communism and his opposition to appeasement, he found himself in the same camp as Winston Churchill and other right-wing political figures in the Conservative Party. The vast majority of those on the left in Britain were sympathetic to the Soviet Union and were willing to do whatever was needed to avoid a war with Nazi Germany.

He found it embarrassing but as he pointed out in an article written in July 1938, why those on the right were willing to do deals with Stalin in order to combat Hitler. The main reason was that the "Fascist powers menace the British Empire". He goes onto argue that the function of the "Conservative anti-Fascists... is to be the liaison officers. The average English left-winger is now a good imperialist." The Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism in Europe "has had a catalytic effect upon English opinion, bringing into being combinations which no one could have foreseen a few years ago". (30)

Orwell decided that he was not going to be put off by his unpleasant bed-fellows. He believed the best defence against fascism was democracy. But he feared that the British people, like those in Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain, would be persuaded to give up their democratic rights in order to be led by dictators. "The radio, press-censorship, standardized education and the secret police have altered everything. Mass-suggestion is a science of the last twenty years, and we do not yet know how successful it will be." (31)

In 1939 Clarence Streit published a book called Union Now: A Proposal for a Federal Union. He suggested that the 15 major countries that had democratic institutions should join together to form "a common government, common money and complete internal free trade". Other countries would be admitted to the Union when and if they "proved themselves worthy". Streit goes on to argue that the combined strength would be so great as to make any military attack on them hopeless. Orwell, agreed that Streit was probably right about the protection such a system would give Britain in the short-term but totally rejected the idea of a "political and economic union". He disliked the idea of being ruled by an un elected bureaucracy that in "essence" was a "mechanism for exploiting cheap labour - under the heading of democracies!" Orwell ends the review by stating that the best defence people have in a capitalist world is the democratic form of government. (32)

Eastern Service of BBC

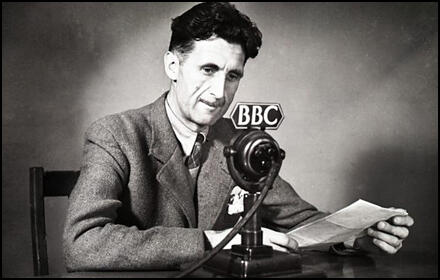

Orwell published Coming up for Air in 1939. In August 1941 Orwell began work for the Eastern Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). His main task was to write the scripts for a weekly news commentary on the Second World War. Orwell's scripts were broadcast to the people of India between the end of 1941 and early 1943. During this period Orwell also worked for the Observer newspaper.

In 1943 Aneurin Bevan, the editor of the socialist journal Tribune, recruited George Orwell to write a weekly column, As I Please. Orwell's plain, lucid style, made him highly effective as a campaigning journalist and some of his best writing was done during this period.

In a famous article in The Evening Standard he argued: "The Home Guard could only exist in a country where men feel themselves free. The totalitarian states can do great things, but there is one thing they cannot do: they cannot give the factory-worker a rifle and tell him to take it home and keep it in his bedroom." (33)

George Orwell: Animal Farm

George Orwel's next book, Animal Farm, was a satire in fable form of the communist revolution in Russia. The book, heavily influenced by his experiences of the way communists behaved during the Spanish Civil War, upset many of his left-wing friends and his former publisher, Victor Gollancz, rejected it. He told Orwell's agent: "I am highly critical of many aspects of internal and external Soviet policy: but I could not possibly publish a general attack of this nature." (34)

His friend, A. J. Ayer, pointed out: "Though he held no religious belief, there was something of a religious element in George's socialism. It owed nothing to Marxist theory and much to the tradition of English Nonconformity. He saw it primarily as an instrument of justice. What he hated in contemporary politics, almost as much as the abuse of power, was the dishonesty and cynicism which allowed its evils to be veiled. When I first got to know him, he had written but not yet published Animal Farm, and while he believed that the book was good he did not foresee its great success. He was to be rather dismayed by the pleasure that it gave to the enemies of any form of socialism, but with the defeat of fascism in Germany and Italy he saw the Russian model of dictatorship as the most serious threat to the realization of his hopes for a better world." (35)

Animal Farm was published on 17th August 1945. The first impression of only 4,500 soon sold out. As a result of the post-war paper shortage, it was not until November that a second impression of 10,000 copies was printed. That also sold out very quickly and from that time it has never stopped reprinting. Bernard Crick has argued: "Overnight Orwell's name became famous. Orwell-like became a synonym for moral seriousness expressed with humour, simplicity and subtlety intertwined." (36)

George Orwell was upset that so many took his left-wing critique of Stalinism as an attack on Socialism. In an article, Why I Write, published in September 1946, Orwell pointed out: "In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows." (37)

George Orwell: Nineteen Eighty-Four

In November 1944, George Orwell received a letter from Professor Gleb Struve, an expert on Russian literature, about a book he had just read. It was a novel by Yevgeny Zamyatin, entitled We. The book had originally been written in 1920-21 but had not been published in the Soviet Union because it was seen as being hostile to the Bolshevik government. It has been argued that it was the first anti-utopian novel ever written and is a satire on life in a collectivist state in the future. (38)

Zamyatin began writing We in 1920. People in this new society called One State, have numbers rather than names, wear identical uniforms and live in buildings built of glass. The people are ruled by the Benefactor and policed by the Guardians. One State is surrounded by a wall of glass and outside is an untamed green jungle. The hero of We is D-503, a mathematician who is busy building Integral, a gigantic spaceship which will eventually go to other planets to spread the joy of the One State. D-503 is happy with his life until he falls in love with I-330, a member of Mephi, a revolutionary organization living in the jungle. D-503 now joins the plot to take over Integral and use it as a weapon to destroy One State. However, the conspirators are arrested by the Guardians and the Benefactor decides that action must be taken to prevent further revolts. D-503 like the rest of the people living in One State, is forced to undergo the Great Operation, which destroys the part of the brain which controls passion and imagination. (39)

George Orwell showed interest in reading the book and Gleb Struve sent him a copy that had been published in France. (40) Orwell thanked Gleb Struve for sending him the book: "I am interested in that kind of book and even keep making notes for one myself that may get written sooner or later." (41)

During this period of research, Orwell also read Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, a novel that had been published in 1932. Set in the 26th century the world has attained a kind of Utopia, in which the means of production are in state ownership and the principle "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need" is rigorously applied. It is a society where citizens are engineered through artificial wombs and childhood indoctrination programmes into predetermined classes (or castes) based on intelligence and labour. Biological engineering fits the different categories of workers – Alphas, Betas, Gammas, etc. – to their stations in life and universal happiness is preserved by psychotropic drugs. It is probably no coincidence that the main rebel in the novel is an Alpha-Plus (the upper class of the society) is named Marx. (42)

George Orwell rejected the perversion of happiness, which Aldous Huxley in Brave New World and Yevgeny Zamyatin in We both made the motivating forces as an adequate account of the new despotisms. Orwell saw these as optimistic visions of the future. In one article he wrote in September 1944 Orwell claimed: "Since about 1930 the world has given no reason for optimism whatever. Nothing is in sight except a welter of lies, hatred, cruelty and ignorance, and beyond our present troubles loom vaster ones which are only now entering into the European consciousness. It is quite possible that man's major problems will never be solved. But it is also unthinkable… So you get the quasi-mystical belief that for the present there is no remedy, all political action is useless but that someone in space and time will cease to be the miserable brutish thing it is now." (43)

Orwell's view of the future was illustrated in a letter he wrote to one of his readers. "I think you overestimate the danger of a Brave New World – i.e. a completely materialistic vulgar civilisation based on hedonism. I would say that the danger of that kind of thing is past and that we are in danger of quite a different kind of world, the centralised slave state, ruled over by a small clique who are in effect a new ruling class, though they might be adoptive rather than hereditary. Such a state would not be hedonistic, on the contrary its dynamic would come from some kind of rabid nationalism and leader-worship kept going by literally continuous war… I see no safeguard against this except (a) war-weariness and distaste for authoritarianism which may follow the present war, and (b) the survival of democratic values among the intelligentsia." (44)

Orwell was especially worried about how "intellectuals" would respond in the years following the Second World War. "The interconnection between sadism, masochism, success worship, power worship, nationalism and totalitarianism is a huge subject whose edges have barely been scratched, and even to mention it is considered somewhat indelicate… Fascism is often loosely equated with sadism, but nearly always by people who see nothing wrong in the most slavish worship of Stalin. The truth is, of course, that the countless English intellectuals who kiss the arse of Stalin are not different from the minority who gave their allegiance to Hitler or Mussolini… All of them are worshipping power and successfully cruelty… The common people, on the whole, are still living in the world of absolute good and evil from which the intellectuals have long since escaped. " (45)

Orwell's mood became even darker when his wife Eileen, aged 39, died of a heart-attack on 29th March 1945 in Newcastle under anaesthetic during what was believed to be a routine operation. The statement on her death certificate was clearly meant to absolve the doctors of any blame: "Cardiac failure whilst under anaesthetic of ether and chloroform skilfully and properly administered for operation for removal of uterus." (46)

In a letter that he wrote to his friend, Lydia Jackson, he pointed out: "The only consolation is that I don't think she suffered, because she went to the operation, apparently, not expecting anything to go wrong, and never recovered consciousness… Her death was especially cruel because she had become so devoted to Richard… It is a shame Eillen should have died just when he is becoming so charming, however, she did enjoy very much being with him during her last months of life." (47)

Orwell welcomed the Labour Party victory in the 1945 General Election. He was especially impressed with Aneurin Bevan who had been appointed as Minister of Health and Minister of Housing: "He is more of an extremist and more of an internationalist than the average Labour M.P., and it is the combination of this with his working-class origin that makes him an interesting and unusual figure… Bevan thinks and feels as a working man. He knows how the scales are weighted against anyone with less than £5 a week… He seems equally at home in all kinds of company. It is difficult to imagine anyone less impressed by social status or less inclined to put on airs with subordinates… Those who have worked with him in a journalistic capacity have remarked with pleasure and astonishment that here at last is a politician who knows that literature exists and will even hold up work for five minutes to discuss a point of style." (48)

In the summer of 1946 Orwell began work on The Last Man in Europe (Nineteen Eighty-Four). He told Humphrey Slater: "I haven't really done any work this summer – actually I have at last started my novel about the future, but I have only done about fifty pages and God knows when it will be finished. However it's something that is started which it wouldn't have been if I hadn't got away from regular journalism for a while." (49)

On 10th April 1947, George Orwell, along with his son Richard, and his youngest sister Avril, travelled to the island of Jura where he had rented a remote farmhouse called Barnhill. He had been ill that winter and was later to discover he was suffering from a fibrotic form of tuberculosis. Friends who visited him were amazed by the amount of writing he was doing. His housekeeper, Susan Watson, remembered him working in bed, lying on the iron bedstead in a dressing-gown. "He always returned to work after tea and often continued typing until three in the morning." (50)

The novel took longer than he expected. He wrote to Celia Kirwan that he was still "struggling with this novel" which he had not got on with as fast as he wanted because "I have been in lousy health most of this year, my chest as usual." (51) Four days later he admitted to Leonard Moore that "I am writing this in bed (inflammation of the lungs), so I shan't be coming up to London in early November as planned." (52)

Orwell finished the first draft of his novel at the end of October and at once took to his bed exhausted. He remained in bed for six weeks. Eventually he agreed to be seen by a doctor who told him he needed to go into a sanatorium in Glasgow for at least four months. On 24th December 1947 he entered Ward 3 of Hairmyres Hospital, East Kilbride, near Glasgow. (53) It was confirmed that Orwell had tuberculosis, and he wrote to John Middleton Murry telling him that he had "the disease which was bound to claim me sooner or later". (54)

Orwell was unhappy with the first draft of The Last Man in Europe. He considered it "a most dreadful mess" and thought that "about two thirds of it will have to be rewritten entirely besides the usual touching up". (55) As one of his biographer's Michael Shelden has pointed out: "A large part of the manuscript has survived, and it reveals that this book did in fact go through a long and apparently painful period of revision. Much of it was written in longhand and then typed, and then revised extensively by hand, and then typed again. He was clearly attempting to create a work which was more advanced in every way than anything he had written before." (56)

Orwell was given an experimental drug streptomycin, which had been developed in America in 1944. It had unpleasant side effects: "I am a lot better, but I had a bad fortnight with the secondary effects of the streptomycin. I suppose with all these drugs it's rather a case of sinking the ship to get rid of the rats." (57) In early May he told David Astor, "My skin is still peeling off in places and my hair is coming out, but otherwise… I am a lot better. They let me up for an hour a day now and let me put a few clothes on, and I think they might let me out if only it was a bit warmer." (58)

In July 1948 Orwell was allowed to return to his rented farmhouse in Jura. By November he had finished the novel, though it was in such a disorganised state that a fair version needed to be typed before it could be submitted to the printers. Orwell tried to arrange for a typist to do the work, but it was impossible to make such arrangements on Jura and so he decided to do the entire job himself. This was difficult as the good effects of streptomycin had faded, and he was once again coughing and wheezing in an alarming way. He struggled to type the book sitting up at a desk and often carried out the task on a sofa with the typewriter balanced on his lap. (59)

Once the transcript had been sent to Fredric Warburg his publisher, Orwell agreed to enter the Cranham Sanatorium in the Cotswold hills between Stroud and Gloucester with views right across the Bristol Channel to the mountains of Wales. "The one chance of surviving, I imagine, is to keep quiet. Don't think I am making up my mind to peg out. On the contrary, I have the strongest reasons for wanting to stay alive. But I want to get a clear idea of how long I am likely to last, and not just be jollied along the way doctors usually do." (60)

Fredric Warburg began negotiations with Harcourt Brace, the American publishers of Animal Farm. They did not like the title, The Last Man in Europe, as they thought it would reduce sales in America. It was suggested it would be better to give a date for this predicted future. That Nineteen Eighty-Four was chosen simply as an inversion of the year 1948. It was argued that people were much more likely to buy a book that had a date that would take place in the reader's lifetime. The true date was around about eighty years after the book was written. In the book, Winston Smith, is in a discussion with Syme a lexicographer involved in compiling a new edition of the Newspeak dictionary. Syme claims the long-term goal was that, by 2050, Newspeak would be the universal language of the Party. (61) The impression is given that this date is not far away. Eventually it was reluctantly agreed to change the title to Nineteen Eighty-Four for commercial reasons. It was chosen as America's book of the month, which at the time was worth a minimum of £40,000. (62)

Nineteen Eighty-Four was published on 8th June 1949 in London and five days later in New York. A year after publication 49,917 copies had been sold in Britain and 170,000 copies in the United States by Harcourt Brace and 190,000 in the Book-of-the-Month Club edition. It never stopped selling. As his biographer, Bernard Crick, pointed out: "How Orwell would have relished such details of the trade, quite apart from the power it gave him of complete financial security, freedom now to write what he liked and when he liked, if he was able." (63)

The book tells the story of Winston Smith, who lives in Great Britain, now known as Airstrip One, that has become a province of the totalitarian superstate Oceania, which is led by Big Brother, a dictatorial leader supported by an intense cult of personality manufactured by the Thought Police. Oceana is made up of America, the British Empire and most of Western Europe.

There are two other superstates, Eurasia that comprises "the whole of the northern part of the European and Asiatic landmass from Portugal to the Bering Strait". Eurasia was formed after the Soviet Union annexed continental Europe following a war between the Soviet Union and Allies. The ideology of Eurasia is Neo-Bolshevism. Eastasia consists of "China and the countries south to it, the Japanese islands, and a large but fluctuating portion of Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet".

Orwell wrote about his fears about superstates in the future in an article for The Partisan Review in 1947: "That the fear inspired by the atomic bomb and other weapons yet to come will be so great that everyone will refrain from using them. This seems to me the worst possibility of all. It would mean the division of the world among two or three vast superstates, unable to conquer one another and unable to be overthrown by any internal rebellion. In all probability their structure would be hierarchic, with a semi-divine caste at the top and outright slavery at the bottom, and the crushing out of liberty would exceed anything that the world has yet seen. Within each state the necessary psychological atmosphere would be kept up by complete severance from the outer world, and by a continuous phony war against rival states. Civilisations of this type might remain static for thousands of years." (64)

This warning in 1947 is still true today. Even after the collapse of communism and the end of the Warsaw Pact in 1991, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) still exists. Every so often, as with the current crisis in Ukraine, politicians call for increased defence spending, and in the UK, the government has decided to pay for by reducing UK's aid budget from 0.5% of gross national income to 0.3% in 2027, "fully funding the investment in defence", which will rise from 2.3% of GDP. (65)

It could be argued that Orwell's claim that the existence of rival superstates will enable them to use fear to control its citizens. Orwell might well have written this if he was still alive today: "So this drive to military spending is based on a series of lies. It also assumes that an arms race and pivot to military spending will enhance security. The opposite is true. Meanwhile we know who is going to suffer: what is spent on military and ‘defence' will come from the budgets for overseas aid, but also care, education, housing, health and other public services. Here we are facing a vicious cut in disability benefits for some of the poorest in society, threats to local government funding, an unprecedented housing crisis, on top of the impoverishment of pensioners, those with families, the sick and disabled." (66)

Winston Smith is a member of the Outer Party, working at the Ministry of Truth, where he rewrites historical records to conform to the state's ever-changing version of history. Orwell was aware that soon after gaining power both Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler ordered that school history books should be rewritten. As Nikita Khrushchev said in 1956: "Historians are dangerous people. They are capable of upsetting everything. They must be directed." (67)

Winston also revises past editions of The Times, while the original documents are destroyed after being dropped into ducts known as memory holes, which lead to an immense furnace. This job provides him with an insight into how the superstate keeps control over its citizens. As he says in Nineteen Eighty-Four: "He who controls the present, controls the past. He who controls the past, controls the future." (68)

In Oceania, the Party created Newspeak, which is a controlled language of simplified grammar and limited vocabulary designed to limit a person's ability for critical thinking. The Newspeak language thus limits the person's ability to articulate and communicate abstract concepts, such as personal identity, self-expression, and free will, which are thoughtcrimes, acts of personal independence that contradict the ideological orthodoxy of the regime. In the appendix to the novel, "The Principles of Newspeak", Orwell explains that Newspeak follows most rules of English grammar, yet is a language characterised by a continually diminishing vocabulary; complete thoughts are reduced to simple terms of simplistic meaning. Orwell tells us: "It was expected that Newspeak would have finally superseded Oldspeak (or Standard English, as we should call it) by about the year 2050. Meanwhile it gained ground steadily, all Party members tending to use Newspeak words and grammatical constructions more and more in their everyday speech." (69)

Winston begins a secret relationship with Julia, a young woman maintaining the novel-writing machines at the Ministry of Truth: "Julia was twenty-six years old... and she worked, as he had guessed, on the novel-writing machines in the Fiction Department. She enjoyed her work, which consisted chiefly in running and servicing a powerful but tricky electric motor... She could describe the whole process of composing a novel, from the general directive issued by the Planning Committee down to the final touching-up by the Rewrite Squad." (70)

Novel writing-machines made no sense in 1948 but in recent years, with the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI), it has become a reality. Companies such as Grammarly offer a novel writing service. In 2023, Death of an Author, a murder mystery written with the pseudonym Aidan Marchine was published. It's the work of the novelist and journalist Stephen Marche, who created the story from three programs, ChatGPT, Sudowrite and Cohere. The book's language, he says, is 95 percent machine generated. (71)

Oceania is constantly worried about internal enemies. The main focus is on Emmanuel Goldstein who was a member of the Inner Party and brother-in-arms of Big Brother before rebelling against the government and forming the resistance group The Brotherhood. This character is based on Leon Trotsky whose real name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein. Every day in Oceania, Goldstein is the subject of the "Two Minutes Hate", a daily programme of propaganda that begins at 11:00 hours; the telescreen shows an over-sized image of Emmanuel Goldstein for the assembled citizens of Oceania to subject to loud insults and contempt. To prolong and deepen the anger of the spectators, the telescreen then shows images of Goldstein walking among the parading soldiers of the current enemy of Oceania - either Eurasia or Eastasia. The Two Minutes Hate programme shows Goldstein as both an ideological enemy of The Party and a traitor aiding the national enemy of Oceania. (72)

Orwell had based Big Brother on Joseph Stalin. Orwell hostility towards Stalin dates back The Spanish Civil War. Despite only being married for a month he immediately decided to go and support the Popular Front government against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. Orwell visited the headquarters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and obtained letters of recommendation from Fenner Brockway and Henry Noel Brailsford. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, to run the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), an anti-Stalinist organisation formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin. (73)

As Orwell fought with POUM he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, George Orwell was able to escape to France on 23rd June. Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. (74)

This upset some pro-communist reviewers of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Kate Carr in The Daily Worker described the book as Cold War propaganda. (75) Arthur Calder-Marshall wrote in the Reynold's News that the object of the book was to abuse and stir up hatred against the Soviet Union and placed George Orwell on "the lunatic fringe" of the Labour Party. (76)

Goldstein also is the author of The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, a treasonous counter-history of the revolution that installed The Party as the government of Oceania and which slanders Big Brother as traitor of the revolution. James Preece has argued that "Goldstein's book represents various suppressed and ‘evil' books of the past, such as Machiavelli's The Prince, Hobbes's Leviathan and, in particular, the works of Trotsky about Stalinist Russia." (77)

Throughout the story, Goldstein appears only in propaganda films on a telescreen. This is followed by the "Two Minutes Hate" sessions where officials of Oceania scream abuse at Goldstein. Of course, today we do not officially have these hate sessions, but we do have something similar carried out by the media that is owned by wealthy individuals if politicians suggest increases in tax on multimillionaires. For example, consider the daily attacks on Jeremy Corbyn when he was leader of the Labour Party. As with the case of Goldstein and Big Brother, the media constantly suggested that Corbyn was a traitor as he supported Putin. Yet, as Peter Oborne showed in his detailed analysis, "the truth is that no modern politician has been more consistent or more prescient when it comes to Putin than Corbyn". (78)

Research carried out by a team at the London School of Economics on the media treatment of Corbyn concluded: "Our analysis shows that Corbyn was thoroughly delegitimised as a political actor from the moment he became a prominent candidate and even more so after he was elected as party leader, with a strong mandate. This process of delegitimisation occurred in several ways: 1) through lack of or distortion of voice; 2) through ridicule, scorn and personal attacks; and 3) through association, mainly with terrorism. All this raises, in our view, a number of pressing ethical questions regarding the role of the media in a democracy. Certainly, democracies need their media to challenge power and offer robust debate, but when this transgresses into an antagonism that undermines legitimate political voices that dare to contest the current status quo, then it is not democracy that is served." (79)

The Party brutally purges out anyone who does not fully conform to their regime, using the Thought Police and constant surveillance through telescreens (two-way televisions), cameras, and hidden microphones. Telescreens are two-way video devices that are an unavoidable source of propaganda and tools of surveillance. Telescreens are the most remarkable prediction that appears in Nineteen Eighty-Four. " Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by the telescreen; moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was, of course, no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork." (80)

Several critics on the left were upset by the fact that in the book Big Brother had introduced the ideology of "Ingsoc" (a Newspeak shortening of "English Socialism"). Even his publisher, Fredric Warburg, was shocked by this and soon after the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four landed on his desk he fired off an internal memorandum stating that: "The political system which prevails is Ingsoc = English Socialism. This I take to be a deliberate and sadistic attack on socialism and socialist parties generally." He added that the book was worth a million votes to the Conservative Party and could plausibly be issued with a preface by Winston Churchill. (81)

Orwell responded to Warburg's complaints that current members of the present British government, such as Clement Attlee, Richard Stafford Cripps and Aneurin Bevan would never willingly sell out socialism, because of their experiences of the 1930s. However, he did fear that in future, Labour politicians would emerge who would find authoritarianism attractive and would be willing to use technology to gain complete control over the party to stop members from challenging the power of the leadership. (82)

Death of George Orwell

On 3rd September 1949 George Orwell entered University College Hospital. He was visited by friends and was keen to discuss the international situation. Richard Rees argued: "To accept death as final was for him a test of intellectual honesty. To care passionately about the fate of mankind after your death was an ethical imperative." (83)

Cyril Connolly also visited Orwell in hospital: "The tragedy of Orwell's life is that when at last he achieved fame and success he was a dying man and knew it. He had fame and was too ill to leave his room, money and nothing to spend it on, love in which he could not participate; he tasted the bitterness of dying. But in his years of hardship he was sustained by a general stocism, by his excitement about what was going to happen next and by his affection for other people." (84)

Orwell told Stephen Spender that it was pointless to answer his communist critics: "There are certain people like vegetarians and Communists whom one cannot answer. You just have to go on saying your say regardless of them, and then the extraordinary thing is that they may start listening." (85)

Another visitor in the spring of 1949 was Sonia Brownell, a young woman he had met at the Horizan Magazine in 1940. John Lehmann wrote "her daring, gay, cynical intelligence and insatiable appetite for knowing everything that went on in the literary world: her revolt against a convent upbringing seemed to provide her life in those days with a kind of inexhaustible rocket fuel." (86)

Sonia came to see he was progressing, and to see what she could do to help him. She felt genuinely sorry for him, but was also more interested in him as a result of the continuing success of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Sonia had always been attracted to men who seemed to have potential for achieving greatness in some branch of culture, and she wanted to encourage and promote that potential. She had sexual relationships with the artists, William Coldstream and Lucian Freud. Sonia also had an affair with Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the French philosopher. She was in love and had hoped he would leave his wife and marry her, but ended the relationship that summer. (87)

Orwell told his publisher, Fredric Warburg, he intended to ask Sonia Brownell to marry him: "As I warned you I might do, I intend getting married again (to Sonia) when I am once again in the land of the living, if I ever am. I suppose everyone will be horrified, but apart from other considerations I really think I should stay alive longer if I were married." (88)

Sonia did not say yes at first and asked for time to think about it. According to Michael Shelden: "She did not love Orwell and had doubts about the merits of his work, but she knew that if they married she would have money and a good cause to fight for - Orwell was the cause and the growing royalties represented the money. Moreover, her job at Horizon was in doubt because Cyril Connolly was threatening to close the magazine at the end of the year, and she was anxious to make some arrangement for securing her future after her editorial job was finished." (89)

Orwell claimed that it was Sonia's idea: "Sonia lives only a few minutes away from here. She thinks we might as well get married while I am still an invalid, because it would give her a better status to look after me especially if, eg. I went somewhere abroad after leaving here. It's an idea, but I think I should have to feel a little less ghastly than at present before I could even face a registrar for 10 minutes. I am much encouraged if none of my friends or relatives seems to disapprove of my remarrying, in spite of this disease." (90)

Orwell married Sonia in hospital on 13th October 1949. The occasion was kept short, so as not to tire him. David Astor entertained Sonia and a small party of mutual friends to a wedding luncheon at the Ritz. The signed menu was brought to Orwell. He was 46 years old, and she was 31. (91)

Orwell made out a new will on 18th January 1950, leaving Sonia his sole beneficiary. He requested that she shoud then leave the residue of the estate to his son Richard in her will. There was no provision for his youngest sister, Avril, who had nursed Orwell through his illness and was looking after Richard.

George Orwell died of tuberculosis on 21st January, 1950.

Primary Sources

(1) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

I had come to Spain with some notion of writing newspaper articles, but I had joined the militia almost immediately, because at that time and in that atmosphere it seemed the only conceivable thing to do. The Anarchists were still in virtual control of Catalonia and the revolution was still in full swing. To anyone who had been there since the beginning it probably seemed even in December or January that the revolutionary period was ending; but when one came straight from England the aspect of Barcelona was something startling and overwhelming. It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle. Practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists; every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and with the initials of the revolutionary parties; almost every church had been gutted and its images burnt. Churches here and there were being systematically demolished by gangs of workmen. Every shop and cafe had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black.

Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said 'Senor' or 'Don' or even 'Usted'; everyone called everyone else 'Comrade' and 'Thou', and said 'Salud!' instead of 'Buenos dias'. Tipping was forbidden by law; almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from an hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy. There were no private motor cars, they had all been commandeered, and all the trams and taxis and much of the other transport were painted red and black. The revolutionary posters were everywhere, flaming from the walls in clean reds and blues that made the few remaining advertisements look like daubs of mud. Down the Ramblas, the wide central artery of the town where crowds of people streamed constantly to and fro, the loud-speakers were bellowing revolutionary songs all day and far into the night. And it was the aspect of the crowds that was the queerest thing of all. In outward appearance it was a town in which the wealthy classes had practically ceased to exist. Except for a small number of women and foreigners there were no 'well-dressed' people at all. Practically everyone wore rough working-class clothes, or blue overalls or some variant of the militia uniform. All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for. Also I believed that things were as they appeared, that this was really a Workers' State and that the entire bourgeoisie had either fled, been killed, or voluntarily come over to the workers' side; I did not realize that great numbers of well-to-do bourgeois were simply lying low and disguising themselves as proletarians for the time being.

(2) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

I had been about ten days at the front when it happened. The whole experience of being hit by a bullet is very interesting and I think it is worth describing in detail.

It was at the corner of the parapet, at five o'clock in the morning. This was always a dangerous time, because we had the dawn at our backs, and if you stuck your head above the parapet it was clearly outlined against the sky. I was talking to the sentries preparatory to changing the guard. Suddenly, in the very middle of saying something, I felt - it is very hard to describe what I felt, though I remember it with the utmost vividness.

Roughly speaking it was the sensation of being at the centre of an explosion. There seemed to be a loud bang and a blinding flash of light all round me, and I felt a tremendous shock - no pain, only a violent shock, such as you get from an electric terminal; with it a sense of utter weakness, a feeling of being stricken and shrivelled up to nothing. The sandbags in front of me receded into immense distance. I fancy you would feel much the same if you were struck by lightning. I knew immediately that I was hit, but because of the seeming bang and flash I thought it was a rifle nearby that had gone off accidentally and shot me. All this happened in a space of time much less than a second. The next moment my knees crumpled up and I was falling, my head hitting the ground with a violent bang which, to my relief, did not hurt. I had a numb, dazed feeling, a consciousness of being very badly hurt, but no pain in the ordinary sense.

The American sentry I had been talking to had started forward. Gosh! Are you hit?' People gathered round. There was the usual fuss - 'Lift him up! Where's he hit? Get his shirt open!' etc., etc. The American called for a knife to cut my shirt open. I knew that there was one in my pocket and tried to get it out, but discovered that my right arm was paralysed. Not being in pain, I felt a vague satisfaction. This ought to please my wife, I thought; she had always wanted me to be wounded, which would save me from being killed when the great battle came. It was only now that it occurred to me to wonder where I was hit, and how badly; I could feel nothing, but I was conscious that the bullet had struck me somewhere in the front of the body. When I tried to speak I found that I had no voice, only a faint squeak, but at the second attempt I managed to ask where I was hit. In the throat, they said. Harry Webb our stretcher-bearer, had brought a bandage and one of the little bottles of alcohol they gave us for field-dressings. As they lifted me up a lot of blood poured out of my mouth, and I heard a Spaniard behind me say that the bullet had gone clean through my neck. I felt the alcohol, which at ordinary times would sting like the devil, splash onto the wound as a pleasant coolness.

They laid me down again while somebody fetched a stretcher. As soon as I knew that the bullet had gone clean through my neck I took it for granted that I was done for. I had never heard of a man or an animal getting a bullet through the middle of the neck and surviving it. The blood was dribbling out of the corner of my mouth. 'The artery's gone,' I thought. I wondered how long you last when your carotid artery is cut; not many minutes, presumably. Everything was very blurry. There must have been about two minutes during which I assumed that I was killed. And that too was interesting - I mean it is interesting to know what your thoughts would be at such a time. My first thought, conventionally enough, was for my wife. My second was a violent resentment at having to leave this world which, when all is said and done suits me so well. I had time to feel this very vividly. The stupid mischance infuriated me. The meaninglessness of it! To be bumped off, not even in battle, but in this stale corner of the trenches, thanks to a moment's carelessness! I thought too of the man who had shot me - wondered what he was like, whether he was a Spaniard or a foreigner, whether he knew he had got me, and so forth. I could not feel any resentment against him. I reflected that as he was a Fascist I would have killed him if I could, but that if he had been taken prisoner and brought before me at this moment I would merely have congratulated him on his good shooting. It may be, though, that if you were really dying your thoughts would be quite different.

(3) George Orwell, The Observer (1st August, 1948)

Whatever may happen to the great public schools when our educational system is reorganized, it is almost impossible that Eton should survive in anything like its present form, because the training it offers was originally intended for a landowning aristocracy and had become an anachronism long before 1939.

It also has one great virtue and that is a tolerant and civilized atmosphere which gives each boy a fair chance of developing his own individuality. The reason is perhaps that, being a very rich school, it can afford a large staff, which means that the masters are not overworked.

(4) George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

Sheffield, I suppose, could justly claim to be called the ugliest town in the Old World: its inhabitants, who want it to be pre-eminent in everything, very likely to make that claim for it. It has a population of half a million and it contains fewer decent buildings than the average East Anglican village of five hundred. And the stench! If at rare moments you stop smelling sulphur it is because you have begun smelling gas. Even the shallow river that runs through the town is usually bright yellow with some chemical or other.

Once I halted in the street and counted the factory chimneys I could see; there were thirty-three of them, but there would have been far more in the air had not been obscured by smoke. One scene especially lingers in my mind. A frightful patch of waste ground trampled bare of grass and littered with newspapers and old saucepans. To the right an isolated row of gaunt four-roomed houses, dark red, blackened by smoke. To the left an interminable visa of factory chimneys, chimney beyond chimney, fading away into a dim blackish haze. Behind me a railway embankment made of slag from furnaces. In front, across the patch of waste ground, a cubical building of red and yellow brick, with the sign 'Thomas Grocock, Haulage Contractor'.

(5) George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

It hardly needs pointing out that at the moment we are in a very serious mess, so serious that even the dullest-witted people find it difficult to remain unaware of it. We are living in a world in which nobody is free, in which hardly anybody is secure, in which it is almost impossible to be honest and to remain alive. For enormous blocks of the working class the conditions of life are such as I have described in the opening chapters of this book, and there is no chance of those conditions showing any fundamental improvement. The very best the English working class can hope for is an occasional temporary decrease in unemployment when this or that industry is artificially stimulated by, for instance, rearmament.

And all the while everyone who uses his brain knows that Socialism, as a world-system and wholeheartedly applied, is a way out. The world is a raft sailing through space with, potentially, plenty of provisions for everybody; the idea that we must all co-operate and see to it that everyone does his fair share of the work and gets his fair share of the provisions seems so blatantly obvious that one would say that no one could possibly fail to accept it unless he had some corrupt motive for clinging to the present system.

(6) George Orwell, Charles Dickens (1939)

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorrit, Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more he has become a national institution himself. In its attitude towards Dickens the English public has always been a little like the elephant which feels a blow with a walking-stick as a delightful tickling. Dickens seems to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody. Naturally this makes one wonder whether after all there was something unreal in his attack upon society.

The truth is that Dickens's criticism of society is almost exclusively moral. Hence the utter lack of any constructive suggestion anywhere in his work. He attacks law, parliamentary government, the educational system and so forth, without ever really suggesting what he would put in their places. Of course it is not necessarily the business of a novelist, or a satirist, to make constructive suggestions, but the point is that Dickens's attitude is at bottom not even destructive. There is no clear sign that he wants the existing order to be overthrown, or that he believes it would make very much difference if it were overthrown. For in reality his target is not so much society as 'human nature'.

It is said that Macaulay refused to review Hard Times because he disapproved of its "sullen Socialism". There is not a line in the book that can properly be called Socialistic; indeed, its tendency if anything is pro-capitalist, because its whole moral is that capitalists ought to be kind, not that workers ought to be rebellious. And so far as social criticism goes, one can never extract much more from Dickens than this, unless one deliberately reads meanings into him. His whole message is one that at first glance looks like an enormous platitude: If men would behave decently the world would be decent.

(7) George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn (1941)

England is a family with the wrong members in control. Almost entirely we are governed by the rich, and by people who stay in positions of command by right of birth. Few if any of these people are consciously treacherous, some of them are not even fools.... The shock of disaster brought a few able men like Bevin to the front, but in general we are commanded by people who managed to live through the years 1931-9 without even discovering that Hitler was dangerous. A generation of the unteachable is hanging upon us like a necklace of corpses.

(8) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (20th December 1941)

The Japanese successes are still very serious for us. At present the pressure of Japanese troops has died down in Malaya, where heavy casualties have been inflicted upon them. Large Indian reinforcements have been landed in Rangoon. The Governor of Hong Kong states that heavy fighting is in progress, on the island itself.

In all this we must remember that the Japanese power, though great, can only aim at a rapid outright victory. The three Axis powers together can produce 60 million tons of steel every year, whereas the USA alone can produce about 88 million. This in itself is not a striking difference. But Japan cannot send help to Germany, and Germany cannot send help to Japan. For the Japanese only produce 7 million tons of steel a year. For steel, as for many other things, they must depend on the stores they have ready.

If the Japanese seem to be making a wild attempt, we must remember that many of them think it their duty to their Emperor, who is their God, to conquer the whole world. This is not a new idea in Japan. Hideyoshi when he died in 1598 was trying to conquer the whole world known to him, and he knew about India and Persia. It was because he failed that Japan closed the country to all foreigners.

In January of this year, to take a recent example, a manifesto appeared in the Japanese press signed by Japanese Admirals and Generals stating that it was Japan's mission to set Burma and India free. Japan was of course to do this by conquering them. What it would be like to be free under the heel of Japan the Chinese can tell us, and the Koreans.

(9) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (28th March 1942)

The Daily Mirror, one of the most widely read of English newspapers, has been threatened with suppression because of its violent and sometimes irresponsible criticisms of the Government. The question was debated in both Houses of Parliament with the greatest vigour. This may seem a waste of time in the middle of a world war, but in fact it is evidence of the extreme regard for freedom of the press which exists in this country. It is very unlikely that the Daily Mirror will actually be suppressed. Even those who are out of sympathy with it politically are against taking so drastic a step, because they know that a free press is one of the strongest supports of national unity and morale, even when it occasionally leads to the publication of undesirable matter. When we look at the newspapers of Germany or Japan, which are simply the mouthpieces of the Government, and then at the British newspapers, which are free to criticise or attack the government in any way that does not actually assist the enemy, we see how profound is the difference between totalitarianism and democracy.

(10) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (6th June 1942)

On two days of this week, two air raids, far greater in scale than anything yet seen in the history of the world, have been made on Germany. On the night of the 30th May over a thousand planes raided Cologne, and on the night of the 1st June, over a thousand planes raided Essen, in the Ruhr district. These have since been followed up by two further raids, also on a big scale, though not quite so big as the first two. To realise the significance of these figures, one has got to remember the scale of the air raids made hitherto. During the autumn and winter of 1940, Britain suffered a long series of raids which at that time were quite unprecedented. Tremendous havoc was worked on London, Coventry, Bristol and various other English cities. Nevertheless, there is no reason to think that in even the biggest of these raids more than 500 planes took part. In addition, the big bombers now being used by the RAF carry a far heavier load of bombs than anything that could be managed two years ago. In sum, the amount of bombs dropped on either Cologne or Essen would be quite three times as much as the Germans ever dropped in any one of their heaviest raids on Britain. (Censored: We in this country know what destruction those raids accomplished and have therefore some picture of what has happened in Germany.) Two days after the Cologne raid, the British reconnaissance planes were sent over as usual to take photographs of the damage which the bombers had done, but even after that period, were unable to get any photographs because of the pall of smoke which still hung over the city. It should be noticed that these 1000-plane raids were carried out solely by the RAF with planes manufactured in Britain. Later in the year, when the American airforce begins to take a hand, it is believed that it will be possible to carry out raids with as many as 2,000 planes at a time. One German city after another will be attacked in this manner. These attacks, however, are not wanton and are not delivered against the civilian population, although non-combatants are inevitably killed in them.

Cologne was attacked because it is a great railway junction in which the main German railroads cross each other and also an important manufacturing centre. Essen was attacked because it is the centre of the German armaments industry and contains the huge factories of Krupp, supposed to be the largest armaments works in the world. In 1940, when the Germans were bombing Britain, they did not expect retaliation on a very heavy scale, and therefore were not afraid to boast in their propaganda about the slaughter of civilians which they were bringing about and the terror which their raids aroused. Now, when the tables are turned, they are beginning to cry out against the whole business of aerial bombing, which they declare to be both cruel and useless. The people of this country are not revengeful, but they remember what happened to themselves two years ago, and they remember how the Germans talked when they thought themselves safe from retaliation. That they did think themselves safe there can be little doubt. Here, for example, are some extracts from the speeches of Marshal Goering, the Chief of the German Air Force. "I have personally looked into the air-raid defences of the Ruhr. No bombing planes could get there. Not as much as a single bomb could be dropped from an enemy plane', August 9th, 1939. "No hostile aircraft can penetrate the defences of the German air force", September 7th, 1939. Many similar statements by the German leaders could be quoted.

(11) George Orwell, Why I Write (September, 1946)

I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:

1. Sheer egotism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in children, etc. etc.

2. Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed.

3. Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

4. Political purpose - using the word 'political' in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people's idea of the kind of society that they should strive after.

It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature - taking your nature to be the state you have attained when you are first adult - I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.

Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows.

(12) A. J. Ayer, Part of My Life (1977)

Another new friend that I made at this time in Paris was George Orwell, who was then a foreign correspondent for the Observer. He had been in College at Eton in the same election as Cyril Connolly, but had left before I came there. I first heard of him in 1937 when he published The Road to Wigan Pier for Gollancz's Left Book Club. By the time that I met him in Paris, I had also read two of his other autobiographical books, Homage to Catalonia and Down and Out in Paris and London, and greatly admired them both. Though I came to know him well enough for him to describe me as a great friend of his in a letter written to one of our former Eton masters in April 1946, he was not very communicative to me about himself. For instance, he never spoke to me about his wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy, whose death in March 1945 left him in charge of their adopted son, who was still under a year old. I had assumed that it was simply through poverty that he had acquired the material for his book Down and Out in Paris and London by working as a dish-washer in Paris restaurants and living as a tramp in England, before he escaped into private tutoring, but I came to understand that it was also an act of expiation for his having served the cause of British colonialism by spending five years in Burma as an officer of the Imperial Police. Not that he was wholly without respect for the tradition of the British Empire. In the revealing and perceptive essay on Rudyard Kipling, which is reproduced in his book of Critical Essays, he criticizes Kipling for his failure to see "that the map is painted red chiefly in order that the coolie may be exploited," but he goes on to make the point that "the nineteenth century Anglo-Indians ... were at any rate people who did things," and from his talk as well as his writings I gained the impression that for all their philistinism he preferred the administrators and soldiers whom Kipling idealized to the ineffectual hypocrites of what he sometimes called "the pansy left".

Though he held no religious belief, there was something of a religious element in George's socialism. It owed nothing to Marxist theory and much to the tradition of English Nonconformity. He saw it primarily as an instrument of justice. What he hated in contemporary politics, almost as much as the abuse of power, was the dishonesty and cynicism which allowed its evils to be veiled. When I first got to know him, he had written but not yet published Animal Farm, and while he believed that the book was good he did not foresee its great success. He was to be rather dismayed by the pleasure that it gave to the enemies of any form of socialism, but with the defeat of fascism in Germany and Italy he saw the Russian model of dictatorship as the most serious threat to the realization of his hopes for a better world. He was not yet so pessimistic as he had become by the time of his writing 1984. His moral integrity made him hard upon himself and sometimes harsh in his judgement of other people, but he was no enemy to pleasure. He appreciated good food and drink, enjoyed gossip, and when not oppressed by ill-health was very good company. He was another of those whose liking for me made me think better of myself.

(13) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

All this did not make me question communism. But it shook my belief in Stalin's infallibility, in Soviet perfection. It made me eager to re-examine all policies, all ideas, everything. My mind was receptive to new ideas for the first time in many, many years.