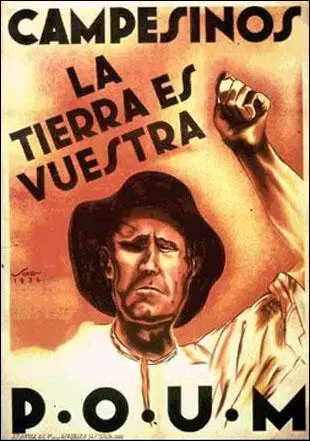

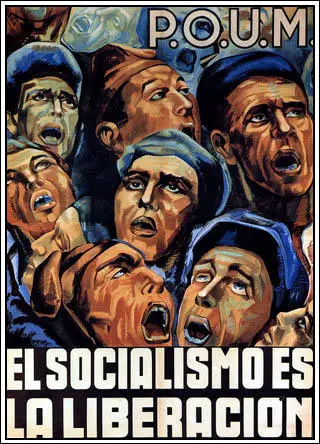

The Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM)

The Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) was formed by Andres Nin and Joaquin Maurin in 1935. A revolutionary anti-Stalinist Communist party it was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Leon Trotsky. The group supported the collectivization of the means of production and agreed with Trotsky's concept of permanent revolution. As a result of Maurin's involvement, POUM was very strong in Catalonia. In most areas of Spain it made little impact and in 1935 POUM is estimated to have only around 8,000 members. (1)

After the Popular Front gained victory POUM supported the government but their radical policies such as nationalization without compensation, were not introduced. During the Spanish Civil War the Workers Party of Marxist Unification grew rapidly and by the end of 1936 it was 30,000 strong with 10,000 in its own militia. Luis Companys attempted to maintain the unity of the coalition of parties in Barcelona. POUM was disliked by the Spanish Communist Party. As Patricia Knight has pointed out: "It did not subscribe to all of Trotsky's views and its best described as a Marxist party which was critical of the Soviet system and particularly of Spain's policies. It was therefore very unpopular with the Communists." (2)

Soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the journalist, George Orwell, decided, despite only being married for a month, to go and support the Popular Front government against the fascist forces led by General Francisco Franco. He contacted John Strachey who took him to see Harry Pollitt, the General Secretary of Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Orwell later recalled: "Pollitt after questioning me, evidently decided that I was politically unreliable and refused to help me. He also tried to frighten me out of going by talking a lot about Anarchist terrorism." (3)

Orwell visited the headquarters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and obtained letters of recommendation from Fenner Brockway and Henry Noel Brailsford. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in December 1936 and went to see John McNair, to run the ILP's political office. The ILP was affiliated with the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). As a result of an ILP fundraising campaign in England, the POUM had received almost £10,000, as well as an ambulance and a planeload of medical supplies. (4)

It has been pointed out by D. J. Taylor, that McNair was "initially wary of the tall ex-public school boy with the drawling upper-class accent". (5) McNair later recalled: "At first his accent repelled my Tyneside prejudices... He handed me his two letters, one from Fenner Brockway, the other from H.N. Brailsford, both personal friends of mine. I realised that my visitor was none other than George Orwell, two of whose books I had read and greatly admired." Orwell told McNair: "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism". Orwell told him that he was also interested in writing about the "situation and endeavour to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France." (6) Orwell also talked about producing a couple of articles for The New Statesman. (7)

McNair went to see Orwell at the Lenin Barracks a few days later: "Gone was the drawling ex-Etonian, in his place was an ardent young man of action in complete control of the situation... George was forcing about fifty young, enthusiastic but undisciplined Catalonians to learn the rudiments of military drill. He made them run and jump, taught them to form threes, showed them how to use the only rifle available, an old Mauser, by taking it to pieces and explaining it." (8)

In January 1937 George Orwell, given the rank of corporal, was sent to join the offensive at Aragón. The following month he was moved to Huesca. On 10th May, 1937, Orwell was wounded by a Fascist sniper. He told Cyril Connolly "a bullet through the throat which of course ought to have killed me but has merely given me nervous pains in the right arm and robbed me of most of my voice." He added that while in Spain "I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before." (9)

After the Soviet consul, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, threatened the suspension of Russian aid, Negrin agreed to sack Andres Nin as minister of justice in December 1936. Nin's followers were also removed from the government. However, as Hugh Thomas has made clear: "The POUM were not Trotskyists, Nin having broken with Trotsky on entering the Catalan government and Trotsky having spoken critically of the POUM. No, what upset the communists was the fact that the POUM were a serious group of revolutionary Spanish Marxists, well-led, and independent of Moscow." (10)

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. On 16th June, Andres Nin and the leaders of POUM were arrested. Also taken into custody were officials of those organisations considered to be under the influence of Trotsky, the National Confederation of Trabajo and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica. (11)

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." Orlov later claimed that "the decision to perform an execution abroad, a rather risky affair, was up to Stalin personally. If he ordered it, a so-called mobile brigade was dispatched to carry it out. It was too dangerous to operate through local agents who might deviate later and start to talk." (12)

Orlov ordered the arrest of Nin. George Orwell explained what happened to Nin in his book, Homage to Catalonia (1938): "On 15 June the police had suddenly arrested Andres Nin in his office, and the same evening had raided the Hotel Falcon and arrested all the people in it, mostly militiamen on leave. The place was converted immediately into a prison, and in a very little while it was filled to the brim with prisoners of all kinds. Next day the P.O.U.M. was declared an illegal organization and all its offices, book-stalls, sanatoria, Red Aid centres and so forth were seized. Meanwhile the police were arresting everyone they could lay hands on who was known to have any connection with the P.O.U.M." (13)

Nin who was tortured for several days. Jesus Hernández, a member of the Communist Party, and Minister of Education in the Popular Front government, later admitted: "Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the dry method. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin resisted the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days his face was a shapeless mass of flesh." Nin was executed on 20th June 1937. (14)

Cecil D. Eby claims that Nin was murdered by "a German hit squad from the International Brigades". The Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party of the United States, reported that "individuals and cells of the enemy had been eliminated like infestations of termites." Eby goes on to argue that the "nearly maniacal purge of putative Trotskyists in the late spring of 1937" displaced the "war against Fascism". (15)

As George Orwell had been fighting with Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) he was identified as an anti-Stalinist and the NKVD attempted to arrest him. Orwell was now in danger of being murdered by communists in the Republican Army. With the help of the British Consul in Barcelona, Orwell, John McNair and Stafford Cottman were able to escape to France on 23rd June, 1937. (16)

Many of Orwell's fellow comrades were not so lucky and were captured and executed. When he arrived back in England he was determined to expose the crimes of Stalin in Spain. However, his left-wing friends in the media, rejected his articles, as they argued it would split and therefore weaken the resistance to fascism in Europe. He was particularly upset by his old friend, Kingsley Martin, the editor of the country's leading socialist journal, The New Statesman, for refusing to publish details of the killing of the anarchists and socialists by the communists in Spain. Left-wing and liberal newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, as well as the right-wing Daily Mail and The Times, joined in the cover-up. (17)

Orwell did managed to persuade the New English Weekly to publish an article on the reporting of the Spanish Civil War. "I honestly doubt, in spite of all those hecatombs of nuns who have been raped and crucified before the eyes of Daily Mail reporters, whether it is the pro-Fascist newspapers that have done the most harm. It is the left-wing papers, the News Chronicle and the Daily Worker, with their far subtler methods of distortion, that have prevented the British public from grasping the real nature of the struggle." (18)

In another article in the magazine he explained how in "Spain... and to some extent in England, anyone professing revolutionary Socialism (i.e. professing the things the Communist Party professed until a few years ago) is under suspicion of being a Trotskyist in the pay of Franco or Hitler... in England, in spite of the intense interest the Spanish war has aroused, there are very few people who have heard of the enormous struggle that is going on behind the Government lines. Of course, this is no accident. There has been a quite deliberate conspiracy to prevent the Spanish situation from being understood." (19)

George Orwell wrote about his experiences of the Spanish Civil War in Homage to Catalonia. The book was rejected by Victor Gollancz because of its attacks on Joseph Stalin. During this period Gollancz was accused of being under the control of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). He later admitted that he had come under pressure from the CPGB not to publish certain books in the Left Book Club: "When I got letter after letter to this effect, I had to sit down and deny that I had withdrawn the book because I had been asked to do so by the CP - I had to concoct a cock and bull story... I hated and loathed doing this: I am made in such a way that this kind of falsehood destroys something inside me." (20)

The book was eventually published by Frederick Warburg, who was known to be both anti-fascist and anti-communist, which put him at loggerheads with many intellectuals of the time. The book was attacked by both the left and right-wing press. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years. As Bernard Crick has pointed out: "Its literary merits were hardly noticed... Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style." (21)

It is believed that Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov originally intended a trial in Spain on the model of the Moscow trials, based on the confessions of people like Nin. This idea was abandoned and instead several anti-Stalinists in Spain died in mysterious circumstances. This included Robert Smillie, the English journalist who was a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Erwin Wolf, ex-secretary of Trotsky, the Austrian socialist Kurt Landau, the journalist, Marc Rhein, the son of Rafael Abramovich, a former leader of the Mensheviks, and José Robles, a Spanish academic who held independent socialist views. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

The P.O.U.M. (Partido Obrero de Unificacion Marxista) was one of those dissident Communist parties which have appeared in many countries in the last few years as a result of the opposition to 'Stalinism'; i.e. to the change, real or apparent, in Communist policy. It was made up partly ofex-Communist and partly of an earlier party, the Workers' and Peasants' Bloc. Numerically it was a small party, with not much influence outside Catalonia, and chiefly important because it contained an unusually high proportion of politically conscious members. In Catalonia its chief stronghold was Lerida. It did not represent any block of trade unions. The P.O.U.M. militiamen were mostly C.N.T. members, but the actual party-members generally belonged to the U.G.T. It was, however, only in the C.N.T. that the P.O.U.M. had any influence.

(2) Franz Borkenau, Spanish Cockpit: An Eyewitness Account of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Political and Social Conflicts of the Spanish Civil War (1937)

It must be explained, in order to make intelligible the attitude of the communist police, that Trotskyism is an obsession with the communists in Spain. As to real Trotskyism, as embodied in one section of the POUM, it definitely does not deserve the attention it gets, being quite a minor element of Spanish political life. Were it only for the real forces of the Trotskyists, the best thing for the communists to do would certainly be not to talk about them, as nobody else would pay any attention to this small and congenitally sectarian group. But the communists have to take account not only of the Spanish situation but of what is the official view about Trotskyism in Russia. Still, this is only one of the aspects of Trotskyism in Spain which has been artificially worked up by the communists. The peculiar atmosphere which today exists about Trotskyism in Spain is created, not by the importance of the Trotskyists themselves, nor even by the reflex of Russian events upon Spain; it derives from the fact that the communists have got into the habit of denouncing as a Trotskyist everybody who disagrees with them about anything. For in communist mentality, every disagreement in political matters is a major crime, and every political criminal is a Trotskyist. A Trotskyist, in communist vocabulary, is synonymous with a man who deserves to be killed. But as usually happens in such cases, people get caught themselves by their own demagogic propaganda. The communists, in Spain at least, are getting into the habit of believing that people whom they decided to call Trotskyists, for the sake of insulting them, are Trotskyists in the sense of co-operating with the Trotskyist political party. In this respect the Spanish communists do not differ in any way from the German Nazis. The Nazis call everybody who dislikes their political regime a 'communist' and finish by actually believing that all their adversaries are communists; the same happens with the communist propaganda against the Trotskyists. It is an atmosphere of suspicion and denunciation, whose unpleasantness it is difficult to convey to those who have not lived through it. Thus, in my case, I have no doubt that all the communists who took care to make things unpleasant for me in Spain were genuinely convinced that I actually was a Trotskyist.

(3) Edward Knoblaugh, Correspondent in Spain (1937)

Largo Caballero began to realize the need for immediate drastic action. As president of the U.G.T., he summoned the sub-leaders of this Revolutionary Socialist group and impressed upon them the desperateness of the situation. The result was a round-table conference among the U.G.T., the heads of the Syndicalists National Confederation of Labor (C.N.T.), The Federation of Iberian Anarchists (F.A.I.), The Trotsky Communists (Partido Obrero Unificado Marxists - P.O.U.M.), The Stalin Communists and the Left Republicans. In the first agreement which these divergent factions had been able to reach since the beginning of the war they approved the immediate mobilization of all able-bodied men in Loyalist territory. A decree to this effect was issued. Whether they wanted to join or not, all men between the ages of 20 and 45 were pressed into military service. From this moment on, the Loyalist army ceased to be a voluntary army.

(4) John Dos Passos, The Villages Are the Heart of Spain (1937)

The headquarters of the unified Marxist party (P.O.U.M.). It's late at night in a large bare office furnished with odds and ends of old furniture. At a bit battered fake Gothic desk out of somebody's library. Andres Nin sits at the telephone. I sit in a mangy overstuffed armchair. On the settee opposite me sits a man who used to be editor of a radical publishing house in Madrid. We talk in a desultory way with many pauses about old times in Madrid, about the course of the war. They are telling me about the change that has come over the population of Barcelona since the great explosion of revolutionary feeling that followed the attempted military coup d'etat and swept the fascists out of Catalonia in July. 'You can even see it in people's dress,' said Nin from the telephone laughing. 'Now we're beginning to wear collars and ties again but even a couple of months ago everybody was wearing the most extraordinary costumes... you'd see people on the street wearing feathers.'

Nin was wellbuilt and healthylooking and probably looked younger than his age; he had a ready childish laugh that showed a set of solid white teeth. From time to time as we were talking the telephone would ring and he would listen attentively with a serious face. Then he'd answer with a few words too rapid for me to catch and would hang up the receiver with a shrug of the shoulders and come smiling back into the conversation again. When he saw that I was begin- ning to frame a question he said, 'It's the villages. . . They want to know what to do.' 'About Valencia taking over the police services?' He nodded. 'What are they going to do?' 'Take a car and drive through the suburbs of Barcelona, you'll see that all the villages are barricaded. The committees are all out on the streets with machine guns.' Then he laughed. 'But maybe you had better not.'

'He'd be all right,' said the other man. 'They have great respect for foreign journalists.' 'Is it an organized movement?' 'It's complicated. . . in Bellver our people want to know whether they ought to move against the anarchists. In other places they are with them. You know Spain.'

It was time for me to push on. I shook hands with Nin and with a young Englishman who also is dead now, and went out into the rainy night. Since then Nin has been killed and his party suppressed.

(5) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

I have spoken of the militia 'uniform', which probably gives a wrong impression. It was not exactly a uniform. Perhaps a 'multiform' would be the proper name for it. Everyone's clothes followed the same general plan, but they were never quite the same in any two cases. Practically everyone in the army wore corduroy knee-breeches, but there the uniformity ended. Some wore puttees, others corduroy gaiters, others leather leggings or high boots. Everyone wore a zipper jacket, but some of the jackets were of leather, others of wool and of every conceivable colour. The kinds of cap were about as numerous as their wearers. It was usual to adorn the front of your cap with a party badge, and in addition nearly every man wore a red or red and black handkerchief round his throat. A militia column at that time was an extraordinary-looking rabble. But the clothes had to be issued as this or that factory rushed them out, and they were not bad clothes considering the circumstances. The shirts and socks were wretched cotton things, however, quite useless against cold. I hate to think of what the militiamen must have gone through in the earlier months before anything was organized. I remember coming upon a newspaper of only about two months earlier in which one of the P.O.U.M. leaders, after a visit to the front, said that he would try to see to it that "every militiaman had a blankt"'. A phrase to make you shudder if you have ever slept in a trench.

On my second day at the barracks there began what was comically called 'instruction'. At the beginning there were frightful scenes of chaos. The recruits were mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen from the back streets of Barcelona, full of revolutionary ardour but completely ignorant of the meaning of war. It was impossible even to get them to stand in line. Discipline did not exist; if a man disliked an order he would step out of the ranks and argue fiercely with the officer. The lieutenant who instructed us was a stout, fresh-faced, pleasant young man who had previously been a Regular Army officer, and still looked like one, with his smart carriage and spick-and-span uniform. Curiously enough he was a sincere and ardent Socialist. Even more than the men themselves he insisted upon complete social equality between all ranks. I remember his pained surprise when an ignorant recruit addressed him as 'Senor'. 'What! Senor? Who is that calling me Senor? Are we not all comrades?' I doubt whether it made his job any easier. Meanwhile the raw recruits were getting no military training that could be of the slightest use to them. I had been told that foreigners were not obliged to attend 'instruction' (the Spaniards, I noticed, had a pathetic belief that all foreigners knew more of military matters than themselves), but naturally I turned out with the others. I was very anxious to learn how to use a machine-gun; it was a weapon I had never had a chance to handle. To my dismay I found that we were taught nothing about the use of weapons. The so-called instruction was simply parade-ground drill of the most antiquated, stupid kind; right turn, left turn, about turn, marching at attention in column of threes and all the rest of that useless nonsense which I had learned when I was fifteen years old. It was an extraordinary form for the training of a guerilla army to take. Obviously if you have only a few days in which to train a soldier, you must teach him the things he will most need; how to take cover, how to advance across open ground, how to mount guards and build a parapet - above all, how to use his weapons. Yet this mob of eager children, who were going to be thrown into the front line in a few days' time, were not even taught how to fire a rifle or pull the pin out of a bomb. At the time I did not grasp that this was because there were no weapons to be had. In the P.O.U.M. militia the shortage of rifles was so desperate that fresh troops reaching the front always had to take their rifles from the troops they relieved in the line. In the whole of the Lenin Barracks there were, I believe, no rifles except those used by the sentries.

(6) Claude Cockburn, The Daily Worker (11th May, 1937)

Thousands of loudspeakers, set up in every public place in the towns and villages of Republican Spain, in the trenches all along the battlefront of the Republic, brought the message of the Communist Party at this fateful hour, straight to the soldiers and the struggling people of this hard-pressed hard-fighting Republic.

The speakers were Valdes, former Councillor of Public Works in the Catalan government, Uribe, Minister of Agriculture in the government of Spain, Diaz, Secretary of the Communist Party of Spain, Pasionaria, and Hemandez, Minister of Education.

Then, as now, in the forefront of everything stand the Fascist menace to Bilbao and Catalonia.

There is a specially dangerous feature about the situation in Catalonia. We know now that the German and Italian agents, who poured into Barcelona ostensibly in order to "prepare" the notorious 'Congress of the Fourth International', had one big task. It was this:

They were - in co-operation with the local Trotskyists - to prepare a situation of disorder and bloodshed, in which it would be possible for the Germans and Italians to declare that they were "unable to exercise naval control on the Catalan coasts effectively" because of "the disorder prevailing in Barcelona", and were, therefore, "unable to do otherwise" than land forces in Barcelona.

In other words, what was being prepared was a situation in which the Italian and German governments could land troops or marines quite openly on the Catalan coasts, declaring that they were doing so "in order to preserve order".

That was the aim. Probably that is still the aim. The instrument for all this lay ready to hand for the Germans and Italians in the shape of the Trotskyist organisation known as the POUM.

The POUM, acting in cooperation with well-known criminal elements, and with certain other deluded persons in the anarchist organisations, planned, organised and led the attack in the rearguard, accurately timed to coincide with the attack on the front at Bilbao.

In the past, the leaders of the POUM have frequently sought to deny their complicity as agents of a Fascist cause against the People's Front. This time they are convicted out of their own mouths as clearly as their allies, operating in the Soviet Union, who confessed to the crimes of espionage, sabotage, and attempted murder against the government of the Soviet Union.

Copies of La Batalla, issued on and after 2 May, and the leaflets issued by the POUM before and during the killings in Barcelona, set down the position in cold print.

In the plainest terms the POUM declares it is the enemy of the People's Government. In the plainest terms it calls upon its followers to turn their arms in the same direction as the Fascists, namely, against the government of the People's Front and the anti-fascist fighters.

900 dead and 2,500 wounded is the figure officially given by Diaz as the total in terms of human slaughter of the POUM attack in Barcelona.

It was not, by any means, Diaz pointed out, the first of such attacks. Why was it, for instance, that at the moment of the big Italian drive at Guadalajara, the Trotskyists and their deluded anarchist friends attempted a similar rising in another district? Why was it that the same thing happened two months before at the time of the heavy Fascist attack at Jarama, when, while Spaniards and Englishmen, and honest anti-fascists of every nation in Europe, were being killed holding Arganda Bridge the Trotskyist swine suddenly produced their arms 200 kilometres from the front, and attacked in the rear?

(7) Claude Cockburn, The Daily Worker (17th May, 1937)

Tomorrow the antifascist forces of the Republic will start rounding up all those scores of concealed weapons which ought to be at the front and are not.

The decree ordering this action affects the whole of the Republic. It is, however, in Catalonia that its effects are likely to be the most interesting and important.

With it, the struggle to "put Catalonia on a war footing", which has been going on for months and was resisted with open violence by the POUM and its friends in the first week of May, enters a new phase.

This weekend may well be a turning-point. If the decree is successfully carried out it means:

First: That the groups led by the POUM who rose against the government last week will lose their main source of strength, namely, their arms.

Second: That, as a result of this, their ability to hamper by terrorism the efforts of the antifascist workers to get the war factories on to a satisfactory basis will be sharply reduced.

Third: That the arms at present hidden will be available for use on the front, where they are badly needed.

Fourth: That in future those who steal arms from the front or steal arms in transit to the front will be liable to immediate arrest and trial as ally of the fascist enemy.

Included in the weapons which have to be turned in are rifles, carbines, machine-guns, machine-pistols, trench mortars, field guns, armoured cars, hand-grenades, and all other sorts of bombs.

The list gives you an idea of the sort of armaments accumulated by the Fascist conspirators and brought into the open for the first time last week.

(8) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

A tremendous dust was kicked up in the foreign antifascist press, but, as usual only one side of the case has had anything like a hearing. As a result the Barcelona fighting has been represented as an insurrection by disloyal Anarchists and Trotskyists who were "stabbing the Spanish Government in the back" and so forth. The issue was not quite so simple as that. Undoubtedly when you are at war with a deadly enemy it is better not to begin fighting among yourselves - but it is worth remembering that it takes two to make a quarrel and that people do not begin building barricades unless they have received samething that they regard as a provocation.

In the Communist and pro-Communist press the entire blame for the Barcelona fighting was laid upon the P.O.U.M. The affair was represented not as a spontaneous outbreak, but as a deliberate, planned insurrection against the Government, engineered solely by the P.O.U.M. with the aid of a few misguided 'uncontrollables'. More than this, it was definitely a Fascist plot, carried out under Fascist orders with the idea of starting civil war in the rear and thus paralysing the Government. The P.O.U.M. was 'Franco's Fifth Column' - a 'Trotskyist' organization working in league with the Fascists.

(9) Tom Murray, Voices From the Spanish Civil War (1986)

Prospects for the future of the Republic were quite good as a sort of a liberal progressive administration. Nobody could call it anything other than that. It wasn't a Government of Socialists. The Republican Government was a Government more or less of Liberals, with Socialists and supporting Communists and so on. And the terrible crime of the P.O.U.M. in my view was that they tried to foster the idea that this was a revolutionary war. It wasn't a revolutionary war. It never had any signs of a revolutionary war. The people of Spain were not revolutionary in the sense of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. They were people concerned to expel the Italians and the Germans from their territory, which was a revolt against an invasion by foreigners into their territory, a foreign invasion which was sponsored by the handful of generals led by Franco. I think it was a great tragedy that at a certain period in the struggle there was fighting behind the lines, instigated in my view by those who believed that it was a revolutionary struggle. And this has got to be clearly understood: it wasn't a revolutionary struggle. It had none of the elements of a revolutionary struggle. It was a struggle for the expulsion of foreign invaders. But the lack of unity ensuing created a terrible handicap.

(10) Bill Alexander, British Volunteers for Liberty (1992)

Early in May 1937 news reached the front of the fighting in the streets of Barcelona between supporters of the POUM aided by some Anarchists, on the one hand, and Government forces on the other. The POUM, who had always been hostile to unity, talked of "beginning the struggle for working-class power."

The news of the fighting was greeted with incredulity consternation and then extreme anger by the International Brigaders. No supporters of the Popular Front Government could conceive of raising the slogan of "socialist revolution" when that Government was fighting for its life against international fascism, the power of whose war-machine was a harsh reality a couple of hundred yards across no-man's-land. The anger in the Brigade against those who fought the Republic in the rear was sharpened by reports of weapons, even tanks, being kept from the front and hidden for treacherous purposes.

(11) Albert Weisbord, Class Struggle (February 1937)

Many advanced workers, disillusioned with the Socialists and Stalinists, have been willing to believe that in the P.O.U.M. there is some hope that the workers will be able to surmount their difficulties and establish the dictatorship of the proletariat and a socialist regime. They point out that the most influential leader, Andreas Nin, was closely connected with Trotsky for many years and was a strong adherent of the theory of peasant revolution. They show that the P.O.U.M. in contradistinction to the other parties in Spain, has called for the rule of the workers, even for Soviets, and has steadily maintained its independence from the other opportunistic organizations.

On the other hand there are those workers who assert that the P.O.U.M. was willing to become a part of the capitalist Catalonian government and that no revolutionary party could possibly have taken such a move. They also declare that the Catalonian government, being capitalist, was as bad as the Madrid government and both were reactionary and against the working class.

In the light of this polemic, it seems to us that the best way to treat the question of revolutionary policy as involved as the actions of P.O.U.M. is to take up the following basic questions:

1. What is the character of the present governments of Madrid and of Catalonia; is it correct to call these governments "reactionary"?

2. Can a revolutionary party at any time enter a government such as that which exists in Madrid or Catalonia?

3. Can the Spanish workers rest their hopes upon the P.O.U.M.?

It seems to us entirely incorrect to estimate the present governments either of Madrid or of Catalonia as "reactionary". Certainly they are not reactionary from the point of view of the bourgeoisie. The present republican-democratic set-up can not be compared with the regime under Alphonso XIII. It is not the habit of Marxists to use the term "reactionary" as a mere expletive. The word "reactionary" means something: it means going backward. A reactionary system is one that would move the social order backward bringing back outworn techniques and methods of production and outworn political forms and social customs.. Alphonso XIII and his forces are clearly reactionary in that sense of the word since they rested state power upon the old feudal grandees and a system of production that was stifling Spain.

The government in Madrid, from the angle of the capitalists, is far from reactionary, since this government intends to unleash all the productive forces of Spain for their benefit. Power will shift from the country to the city, from agriculture to industry, from the landlord to the industrialists and modern capitalist elements. From the capitalist point of view the victory of the present Madrid or Catalonian government means the beginning of the modernization of Spain.

To draw an historical analogy: It might be said that the present Madrid government stands to Alphonso XIII as the French Revolitionary government stood to Louis XVI. There is, however, this vast distinction. In the 18th century the French Revolutionary Government, operating on behalf of modern capitalism, could not help be progressive and clear the road for the new social order. In the 20th century, there has appeared on the horizon a new class, a working class that should be able to make an independent bid for power. No longer tied to the apron strings of capital, the proletariat of Spain is ready to modernize Spain not in the capitalist sense but in the socialist sense. And thus the modernization of Spain in the capitalist sense has to be the work not of a progressive government but of forces that stifle and crush the revolutionary proletariat and the toiling masses.

Many of those who wish to modernize Spain from a bourgeois point of view are now with the forces of Franco precisely for this reason. The insurgents are not of one piece; there are the Carlists and the Bourbonists, but there are also the fascists. The fascists do not wish to bring back the old Spain that has been irrevocably destroyed. They too wish essentially to industrialize and modernize Spain, but they understand clearly that no longer is this the job of revolution - as was the case in France in 1789 - but of counter-revolution.

In this the counter-revolutionary fascists disagree violently with their capitalist brethren who are still behind the Madrid government. The capitalists of the Madrid government who are in the Left Republican Parties, believe that the workers can be controlled, that they will not make a bid for power and that therefore the Madrid government can become, like the government of present day England or of France, a fine vehicle for the development of capital. The fascist capitalists, however, believe that the day is too late for this, that democratic control is too weak, that the working class can no longer be restrained and that the first job of the day is to crush the aspirations of the masses for Socialism. Only thus can capitalism be revived in Spain.

Here, then, are the exploiting classes divided. Generally speaking, it is the big capitalists of heavy industry and the financiers that take the side of the fascists; the landowners go with the monarchists; both units against the present Madrid regime. It is the petty bourgeoisie and the factory owners of small and light industry that tend to support the Madrid Republic or at least not openly fight against it.

Nor can it be said that even from the workers' point of view that either the Catalonian government or the Madrid government was "reactionary". Were these governments engaged in shooting down the working class and putting down the lower orders, were the masses ready to push the revolution forward to socialism and were being kept back by the broad might of these governments, then it might be said that these governments were reactionary in the sense that they were preventing the people from building Socialism, the only system of society that could improve upon the moribund capitalism of the present.

But the fact of the matter is, the masses are more or less imprisoned by the opportunism of the Socialists and Stalinists on the one hand, and the Anarchists and Syndicalists on the other. The Socialists and Stalinists have openly declared that they are not fighting for Socialism but merely for bourgeois democracy. They have become ardent bourgeois democrats and republicans and have no other thought than loyal support of the status quo that was being attacked by the rebel reactionaries. The Socialists and Stalinists do not want Socialism, they do not want even workers' control over production. They make no move to socialize the industries. They do not form Soviets. They do not resists the formation of a new capitalist army under the control of bourgeois officers. They do not break from the Azanas and the Companys, bourgeois leaders of the Madrid and Catelonian governments. They make no effort to carry the revolution forward for the benefit of the people. Instead they carry on bitter war against the Left Wing, especially the P.O.U.M. that tends to go in the revolutionary direction.

The Anarchists also have come out strongly against the dictatorship of the proletariat and it was for this reason that the Anarcho-Syndicalists of the C.N.T. refused to participate in the Asturias revolt of 1934 and quietly saw their own brethren shot down by the Madrid government of those days because the workers refused to pledge themselves to the Asturias revolt that they would not take the power and inaugurate Socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. Today, together with the Socialists and Stalinists, the Anarchists and Syndicalists have also become part of the governmental forces of Madrid and of Catalonia. These Anarchists, who would not fight for the rule of the workers, are quit ready to give their lives for the continuance of Madrid rule, and thus they prove to be basically one with the petty-bourgeois reformists of the Socialist and Stalinist parties.

In the light of the fact that all of the big proletarian organizations, Anarchist, Syndicalist, Socialist and Stalinist support the present governments of Madrid and of Catalonia, it is difficult to call these governments reactionary. They would be reactionary only if the mass organizations were ready to go forward beyond the present capitalist system and were throwing themselves against this government. But for this there would have to be a genuinely revolutionary party guiding the masses. Up to the present, unfortunately, this is not the case; the masses through their organizations are heartily supporting the governmental regimes.

But if the Madrid and Catalonian governments are not reactionary, this does not mean that they are not capitalistic. For anyone to idealize the Madrid governments or the Left Madrid government that exists in Catalonia would be to make a criminal error. There is no such thing as a government without classes and class domination. The class that dominates Madrid and to a weaker degree Catalonia, is the capitalist class.

It is true there has been some talk of socialization of the factories in Catalonia and also in Madrid, but the Socialists and Stalinists have seen to it that it is mostly talk. There have been some spontaneous seizures of the factories by the workers and a degree of worker control over them, but private property in the means of production is still retained intact, on the whole. Foreign property is carefully protected; the property of the agrarian landholder is assured, the petty-bourgeoisie is quieted. During the present civil war, there may have to be some severe measures of confiscation, some degree of nationalization of industry and public utilities, as there was in the days of the Jacobins of the 18th century in France, but the system of private property remains secure. That is the situation today where the Republicans control.

(12) Ilya Ehrenburg, Izvestia, on the May Riots (3rd November, 1937)

I must express the sense of shame which I now feel as a man. The same day that the fascists are busy shooting the women of Asturias, there appeared in the French paper a protest against injustice. But these people did not protest against the butchers of Asturias but rather against the republic who dares to detain fascists and provocateurs of the POUM.

(13) Edward Knoblaugh, Correspondent in Spain (1937)

Juan Negrin, former Minister of Treasury under Largo and a friend of the foreign correspondents, was named Premier to succeed Largo. I had known Negrin for several years and sincerely admired him. Even after the stocky, bespectacled multi-linguist became a cabinet minister he continued his nightly visits to the Miami bar for his after-dinner liqueur. I often chatted with him there, getting angles on the financial situation.

The presence of a moderate Socialist at the head of the new government was a boon to the regime because it strengthened the fiction of a "democratic" government abroad. Largo's ouster, however, produced fresh troubles. Feeling much stronger after its critical first test of strength against the Catalonian Anarcho-Syndicalists, the government had ousted the Anarchist members of the Catalonian Generalitat government and followed this up by excluding the Anarcho-Syndicalists from representation in the new Negrin cabinet.

Largo, it had been thought, would step down gracefully, but, bitterly disappointed and angry, the former Premier immediately began plotting his return to power. The Anarchists, equally bitter at their being deprived of a voice in government, suddenly threw their support to Largo, who adopted as his new campaign slogan the Anarchist cry "We want our social revolution now."

Largo has another important, if less powerful, ally, in the outlawed P.O.U.M. Trotskyites. The disappearance and reported murder of the Trotskyite leader, Andres Nin, added to the bitterness of the P.O.U.M. Nin, one of the foremost revolutionaries in Spain, was arrested last June when the government, at the behest of the Stalin Communists, raided the P.O.U.M. headquarters in Barcelona and arrested many of the members.

It was announced that Nin had been taken first to Valencia and then to Madrid for imprisonment pending trial. When the P.O.U.M., supported by the Anarchists and many of Largo's extreme Socialists, became more and more insistent in their demands that Nin be produced and tried, and the government was unable to dodge the issue any longer, it issued a communiqué to the effect that Nin had "escaped" from the Madrid prison with his guards. Even the Anarchist newspapers were obliged to print this version, but Anarchist and Trotskyite circles were convinced that Nin was murdered enroute to Madrid, and he became a martyr.

Largo regards the present government as bourgeois and counter-revolutionary, and is frankly working for its overthrow. With the opposition to the Negrin government now three-way, neutral observers do not believe that a decisive program can long be avoided. The well-disciplined Communists supporting the Negrin cabinet are confident that if an open fight eventuates, as it seems likely to do either before or after the war, it will have the support of a large percentage of Loyalist Spain. The government will be able to count on its "army within an army." Whether this will be able to cope with the powerful labor unions supporting Largo is problematical.

(14) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

In the Spring of 1937 an organization called the POUM instigated an armed insurrection in Barcelona against the government of the Republic. Consisting of Spanish Trotskyists and Anarchists, the POUM claimed the revolt was an effort at proletarian revolution and the immediate abolition of capitalism in Spain. The government, whose premier was a Socialist, looked upon the uprising as a stab in the back, as treason in the midst of a war against fascism, and proceeded to crush it. We in the International Brigade did not participate in Spain's internal politics and the POUM putsch did not directly affect our units then fighting at the front, but we considered the counter-measures of the government entirely reasonable.

There is a vogue today, set by the late George Orwell, to say the POUM should have been supported and that the government was wrong to crush it. This would mean that the Spanish government should have let itself be overthrown. A comparable situation - perhaps easier for Americans to understand - would be if a group of radicals had organized an armed uprising in Chicago against the Roosevelt government in 1944 when our troops were landing in Normandy. It is hard not to feel that the present-day champions of the POUM seem to want to out-Bolshevik the Bolsheviks.

The POUM claimed that the issue in Spain was proletarian revolution. But this was what the supporters of Franco also claimed, although from the opposite direction. On the other hand, the government and the Communists declared the only issue was democracy versus fascism, and they acted accordingly. Those who think the POUM could have saved Spain should ponder whether the western powers which refused aid to the democratic capitalist government would have helped a revolutionary anti-capitalist POUM regime.

I find it strange, too, that some persons who condemn the Czech Communists for having taken over full power in their country in 1948, can condone the attempt of the POUM to take over in Spain in the mid9t of a life-and-death struggle with fascism.