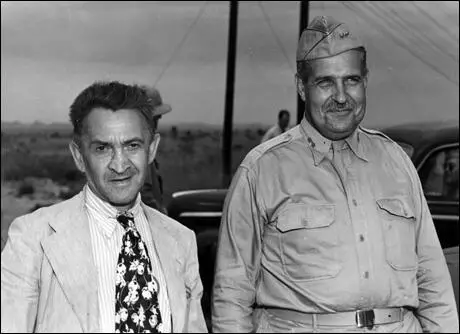

William Laurence

William Laurence was born in Lithuania in 1888. As a young man he developed radical political opinions and in 1905 he was forced to flee from Russia. Laurence moved to the United States and eventually became a science reporter for several leading newspapers and magazines in the country.

Laurence had the ability to translate the complexities of modern science into articles that could be understood by the general public. He had good contacts with the world's leading scientists and in 1940 began writing articles about nuclear research for the New York Times and the Saturday Evening Post. Laurence argued that in future small quantities of U-235, would propel an ocean liner, heat and light entire cities and set off a destructive bomb blast that was equivalent of twenty thousand tons of TNT.

After Pearl Harbor Laurence noticed that scientists in the United States working in this field began to refuse to talk to him. He became convinced that the Allies were involved in a secret atom bomb project. This was confirmed in the summer of 1942 when the United States Office of Censorship wrote to him asking him not to write articles on the potential of nuclear power.

In April 1945 Laurence was contacted by General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project. Groves told Laurence about the project and recruited him to become the official chronicler of the development of the atom bomb. For the next three months he was allowed to interview the scientists working on the project and prepare the press releases needed when this new weapon was used.

Laurence witnessed the first test explosion of an atomic bomb in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico. He also interviewed the crew that took part in the raid on Hiroshima and was on the plane that dropped the atom bomb on Nagasaki.

Articles published by Laurence in the New York Times in 1945 won him the Pulitzer Prize. He was employed as Science Editor of the newspaper between 1956 and 1964.

William Laurence died in Majorca on 19th March, 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) This article by William Laurence about the bombing Nagasaki appeared in several newspapers in August 1945.

We are on our way to bomb the mainland of Japan. Our flying contingent consists of three specially designed B-29 Superforts, and two of these carry no bombs. But our lead plane is on its way with another atomic bomb, the second in three days, concentrating its active substance, and explosive energy equivalent to 20,000, and under favorable conditions, 40,000 tons of TNT.

We have several chosen targets. One of these is the great industrial and shipping center of Nagasaki, on the western shore of Kyushu, one of the main islands of the Japanese homeland.

I watched the assembly of this man-made meteor during the past two days, and was among the small group of scientists and Army and Navy representatives privileged to be present at the ritual of its loading in the Superfort last night, against a background of threatening black skies torn open at intervals by great lightning flashes.

It is a thing of beauty to behold, this "gadget." In its design went millions of man-hours of what is without a doubt the most concentrated intellectual effort in history. Never before had so much brain-power been focused on a single problem.

This atomic bomb is different from the bomb used three days ago with such devastating results on Hiroshima.

I saw the atomic substance before it was placed inside the bomb. By itself it is not at all dangerous to handle. It is only under certain conditions, produced in the bomb assembly, that it can be made to yield up its energy, and even then it gives up only a small fraction of its total contents, a fraction, however, large enough to produce the greatest explosion on earth.

The briefing at midnight revealed the extreme care and the tremendous amount of preparation that had been made to take care of every detail of the mission, in order to make certain that the atomic bomb fully served the purpose for which it was intended. Each target in turn was shown in detailed maps and in aerial photographs. Every detail of the course was rehearsed, navigation, altitude, weather, where to land in emergencies. It came out that the Navy had submarines and rescue craft, known as "Dumbos" and "Super Dumbos," stationed at various strategic points in the vicinity of the targets, ready to rescue the fliers in case they were forced to bail out.

The briefing period ended with a moving prayer by the Chaplain. We then proceeded to the mess hall for the traditional early morning breakfast before departure on a bombing mission.

A convoy of trucks took us to the supply building for the special equipment carried on combat missions. This included the "Mae West," a parachute, a life boat, an oxygen mask, a flak suit and a survival vest. We still had a few hours before take-off time but we all went to the flying field and stood around in little groups or sat in jeeps talking rather casually about our mission to the Empire, as the Japanese home islands are known hereabouts.

In command of our mission is Major Charles W. Sweeney, 25, of 124 Hamilton Avenue, North Quincy, Massachusetts. His flagship, carrying the atomic bomb, is named "The Great Artiste," but the name does not appear on the body of the great silver ship, with its unusually long, four-bladed, orange-tipped propellers. Instead it carried the number "77," and someone remarks that it is "Red" Grange's winning number on the Gridiron.

Major Sweeney's co-pilot is First Lieutenant Charles D. Albury, 24, of 252 Northwest Fourth Street, Miami, Florida. The bombardier upon whose shoulders rests the responsibility of depositing the atomic bomb square on its target, is Captain Kermit K. Beahan, of 1004 Telephone Road, Houston, Texas, who is celebrating his twenty-seventh birthday today.

Captain Beahan has been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and one Silver Oak Leaf Cluster, the Purple Heart, the Western Hemisphere Ribbon, the European Theater ribbon and two battle stars. He participated in the first heavy bombardment mission against Germany from England on August 17, 1942, and was on the plane that transported General Eisenhower from Gibraltar to Oran at the beginning of the North African invasion. He has had a number of hair-raising escapes in combat.