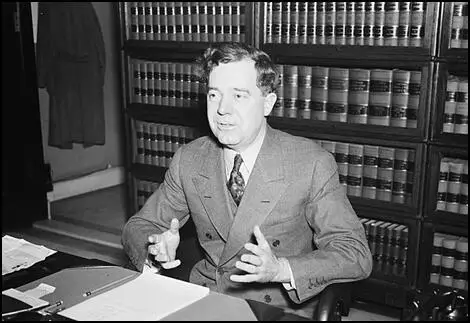

Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long, the seventh of nine children, was born in Winnfield, Louisiana, on 30th August, 1893. After leaving school he worked as a salesman in Texas and Tennessee before enrolling in the Tulane University Law School in New Orleans in 1914. He completed the three-year course in eight months and became a lawyer at the age of 21.

Long established his law practice in Winnfield. He soon developed a reputation as a champion of the common people. He later said "my cases in Court were on the side of the small man - the underdog." He added "I have never taken a suit against a poor man."

A member of the Democratic Party, Long supported S. J. Harper in his campaign against limited employers' liability. Long also successfully defended Harper, an opponent of American involvement in the First World War, after his anti-war activities led to him being charged under the Espionage Act.

In 1918 Long won election as state railroad commissioner for the northern district of Louisiana. The following year he supported John M. Parker, in his successful campaign to become Governor of Louisiana. However, in 1919 Long began attacking Governor Parker for failing to increase taxes on Standard Oil. In 1921 Long became chairman of the Public Services Commission and over the next couple of years successfully achieves lower telephone, gas and electric rates, railroad and streetcar fares and a severance tax on oil.

Long ran for office as Governor of Louisiana in 1928. Education was the main theme of his election campaign. As he pointed out, Louisiana's illiteracy rate of 22 per cent was the highest in the United States. Long's attacks on the utilities industries and the privileges of corporations were popular and he won the election by the largest margin in the state's history (92,941 votes to 3,733).

Once in power Long condemned the state's ruling hierarchy and attempted to replace it with his own supporters. In this way he gained control of the Hospital Board, the Highway Commission, the Levee Board and the Dock Board. He also forced state employees to distribute his newspaper, the Louisiana Progress. Long also attempted to capture the Democratic State Central Committee.

Long's critics accused him of being a dictator but he did introduce important reforms. This included the provision of free school textbooks, free night school courses for adult illiterates and increased expenditure on the state university.

In 1928, Louisiana only had 331 miles of paved roads. When Long gained power he launched an infrastructure programme aimed at building 3,000 miles of roads and establishing schools within walking distance of all the state's white children. To pay for the roads and schools that were built in Louisiana, Long increased taxes on local corporations.

The journalist, Raymond Gram Swing, went to visit Long: "I attended two other sessions with his approval, one of a special meeting of the legislature in the skyscraper statehouse at Baton Rouge, the other of the Ways and Means Committee, both called to take care of thirty-five bills introduced by the Long machine. The Senator was at both meetings running things without the slightest right of membership. Nobody objected. This was Huey's legislature, his committee, his statehouse, his state. At the special session of the legislature, he answered questions from the floor.... In the committee meeting at nine the next morning, Long read and explained each bill, then the chairman put it to a vote, smashing down his gavel. Here, too, he had no right to take part in the proceedings, but no one objected. The committee consisted of fifteen Long supporters and two oppositionists. Three bills were approved in the first six minutes, thirty-five were acted on in seventy minutes, all but one being approved."

Despite his criticisms of the way Long governed, Swing admitted that some of his reforms helped the poor: "This has to be said for Huey Long: he had strong liberal instincts and left to his credit a list of reforms not to be matched in any other Southern state. He shifted the burden of taxation from the poor to those who could afford to bear it. To finance his reforms, he increased the state's indebtedness from $11,000,000 to $150,000,000, but met each increase by new taxation. He passed legislation postponing the payment of private debt. He laid out a system of highways and bridges, and, above all, he dedicated himself to improving the state's education. He remodeled the school system to enable eight-month terms to be maintained in the poorest parishes and provided free textbooks. He strongly supported the Julius Rosenwald campaign against illiteracy, so that 100,000 adults in Louisiana, white and black, learned to read and write in his first term as governor. He backed Louisiana State University, assured it a good faculty, added a medical and dental school, and increased its enrollment from 1,500 to 4,000 in his first term as governor. As governor, he fought the public-utility companies and forced down power and telephone rates. He obtained a reduction of electricity rates in New Orleans. He built a five-million-dollar statehouse, an impressive high-tower building rising on the bank of the Mississippi."

Long also attempted to increase revenues by imposing a new tax on the oil industry. The legislature rejected the measure and attempts were made to impeach Long. He was accused of misappropriating state funds and making illegal loans. However, the Senate failed to convict Long by two votes and afterwards it was claimed he had bribed several senators in order to get the right result.

In 1930 Long was elected to the Senate. To keep full control of Louisiana he installed an old friend, Alvin King, the president of the state senate, to act as governor. In the Senate he was highly critical of President Herbert Hoover and the way his government was dealing with the Great Depression.

William E. Leuchtenburg has argued: "Huey clowned his way into national prominence. A tousled redhead with a cherubic face, a dimpled chin, and a pug nose, he had the physiognomy of a Punchinello. He wore pongee suits with orchid-colored shirts and sported striped straw hats, watermelon-pink ties, and brown and white sport shoes... He had mastered a brand of humor which pricked the pretenses of respectability, which appealed to men convinced that beneath the cloth of the jurist sat the fee-grabbing lawyer, beneath the university professor the carnival faker, and, most of all, beneath the statesman the self-serving politician."

In the summer of 1932 Long took on the Democratic Party machine when he decided to support Hattie Caraway, the first women to be elected to Congress, in her bid to hold her seat in the Senate. Joseph T. Robinson and other leaders of the party in Arkansas were opposed to the idea and told her she would not win the party nomination. Caraway approached Long and he agreed to help her in her campaign and she defeated her nearest competitor by two to one.

Long supported the presidential campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, after his election, he was highly critical of some aspects of the New Deal. He disliked the Emergency Banking Act because it did little to help small, local banks. He bitterly attacked the National Recovery Act for the system of wage and price codes it established. He correctly forecasted that the codes would be written by the leaders of the industries involved and would result in price-fixing. Long told the Senate: "Every fault of socialism is found is this bill, without one of its virtues."

Long also claimed that Roosevelt had done little to redistribute wealth. When Roosevelt refused to introduce legislation to place ceilings on personal incomes, private fortunes and inheritances, Long launched his Share Our Wealth Society. In February 1934. He told the Senate: "Unless we provide for redistribution of wealth in this country, the country is doomed." He added the nation faced a choice, it could limit large fortunes and provide a decent standard of life for its citizens, or it could wait for the inevitable revolution.

Long quoted research that suggested "2% of the people owned 60% of the wealth". In one radio broadcast he told the listeners: "God called: 'Come to my feast.' But what had happened? Rockefeller, Morgan, and their crowd stepped up and took enough for 120,000,000 people and left only enough for 5,000,000 for all the other 125,000,000 to eat. And so many millions must go hungry."

Long's plan involved taxing all incomes over a million dollars. On the second million the capital levy tax would be one per cent. On the third, two per cent, on the fourth, four per cent; and so on. Once a personal fortune exceeded $8 million, the tax would become 100 per cent. Under his plan, the government would confiscate all inheritances of more than one million dollars.

This large fund would then enable the government to guarantee subsistence for everyone in America. Each family would receive a basic household estate of $5,000. There would also be a minimum annual income of $2,000 per year. Other aspects of his Share Our Wealth Plan involved government support for education, old-age pensions, benefits for war veterans and public-works projects.

Some critics pointed out that all wealth was not in the form of money. Most of America's richest people had their wealth in land, buildings, stocks and bonds. It would therefore be very difficult to evaluate and liquidate this wealth. When this was put to Long he replied: "I am going to have to call in some great minds to help me."

Leaders of the Communist Party and Socialist Party also attacked Long's plan. Alex Bittelman, a communist in New York wrote: "Long says he wants to do away with concentration of wealth without doing away with capitalism. This is humbug. This is fascist demagogy." Norman Thomas claimed that Long's Share Our Wealth scheme was insufficient and a dangerous delusion. He added that it was the "sort of talk that Hitler fed the Germans and in my opinion it is positively dangerous because it fools the people."

Long admitted that certain aspects of his scheme was socialistic. He said to a reporter from The Nation: "Will you please tell me what sense there is running on a socialist ticket in America today? What's the use of being right only to be defeated?" On another occasion he argued: "We haven't a Communist or Socialist in Louisiana. Huey P. Long is the greatest enemy that the Communists and Socialists have to deal with."

Some economists claimed that if the Share Our Wealth plan was implemented it would bring an end to the Great Depression. They pointed out that one of the major causes of the economic downturn was the insufficient distribution of purchasing power among the population. If poor families had their incomes increased they would spend this extra money on goods being produced by American industry and agriculture and would therefore stimulate the economy and create more jobs.

Long employed Gerald L. K. Smith, a Louisiana preacher, to travel throughout the South to recruit members for the Share our Wealth Clubs. The campaign was a great success and by 1935 there was 27,000 clubs with a membership of 4,684,000 and a mailing list of over 7,500,000.

Attempts were made to smear Long. One friend wrote that when Long "launched a campaign to limit the size of fortunes a price was set on his head and thugs were employed by big business to rub him from the national picture." Stories began circulating that Long was an alcoholic and to protect himself he gave up drinking and avoided visiting night clubs.

Long's radical ideas did appeal to progressives in the Congress and he gained support from Gerald Nye, William Borah, Henrik Shipstead, Bronson Cutting, Lynn Frazier, Robert LaFollette Jr., John Elmer Thomas, Burton K. Wheeler and George Norris. In October 1933, he published his autobiography, Every Man a King. One reviewer described the book as "unbalanced, vulgar, in many ways ignorant, and quite reckless." Long also began publishing American Progress . Financed by political contributions from his organization in Louisiana, Long mailed it free to his supporters. Normally 300,000 copies were sold per issue but for special editions 1.5 million were printed.

In 1934 Long convened a special session of the legislature in Louisiana and pushed through bills that placed electoral machinery in the governor's hands, outlawing interference by the courts with his use of national guardsmen, and creating his own secret police.

Raymond Gram Swing argued in The Nation in January, 1935. "He (Long) is not a fascist, with a philosophy of the state and its function in expressing the individual. He is plain dictator. He rules, and opponents had better stay out of his way. He punishes all who thwart him with grim, relentless, efficient vengeance. But to say this does not make him wholly intelligible. One does not understand the problem of Huey Long or measure the menace he represents to American democracy until one admits that he has done a vast amount of good for Louisiana. He has this to justify all that is corrupt and peremptory in his methods. Taken all in all, I do not know any man who has accomplished so much that I approve of in one state in four years, at the same time that he has done so much that I dislike. It is a thoroughly perplexing, paradoxical record."

In May 1935 Long began having talks with Charles Coughlin, Francis Townsend, Gerald L. K. Smith, Milo Reno and Floyd B. Olson about a joint campaign to take on President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential elections. Two months later Long announced that his police had discovered a plot to kill him. He now surrounded himself with six armed bodyguards. In August 1935, Long announced his candidacy for the presidency.

A shoe salesman from Chicago wrote a letter to Long: "I voted for President Roosevelt but it seems Wall Street has got him punch drunk. What we need is men with guts to go farther to the left as you advocate." Milo Reno, the leader of the radical Farmers' Holiday Association, introduced Long at a meeting as "the hero whom God in his goodness has vouchsafed to his children" in compensation for "Roosevelt, Wallace, Tugwell and the rest of the traitors."

Over the years, Long had been in constant conflict with Judge Benjamin Pavy of St. Landry Parish. Unable to unseat Pavy in St. Landry Parish, Long decided to gain revenge by having two of the judge's daughters dismissed from their teaching jobs. Long also warned Pavy that if he continued to oppose him he would say that his family had "coffee blood". This was based on the story that Pavy's father-in-law, had a black mistress.

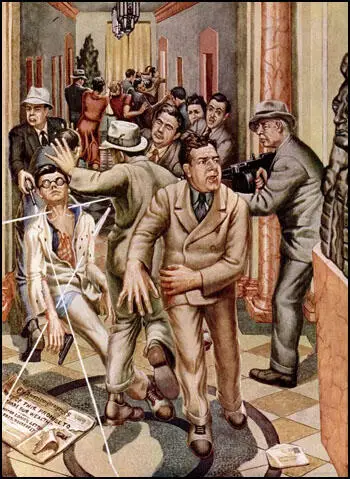

On 8th September, 1935, Pavy's son-in-law, Carl Weiss was told that rumours were circulating that his wife was the daughter of a black man. Weiss was furious when he heard the news and decided to pay Long a visit in the State Capitol Building. Long was in the governor's office, and so he waited by a marble pillar in the corridor. When Long left the office with John Fournet and six bodyguards, Weiss pulled out a .32 automatic and aimed it at Long. Weiss fired and hit Long in the abdomen. The bodyguards opened fire and Weiss died on the spot. A bullets fired by one of the bodyguards ricocheted off the pillar and hit Long in the lower spine.

At first it was thought that Long was not seriously wounded and an operation was carried out to repair his wounds. However, the surgeons had failed to detect that one of the bullets had hit Long's kidney. By the time this was discovered, Long was to weak to endure another operation and died on 10th September, 1935. According to his sister, Lucille Long, his last words were: "Don't let me die, I have got so much to do." His book, My First Days in the White House, was published posthumously.

Primary Sources

(1) Huey Long, Every Man a King (1933)

Conditions were not very good in the Winnfield community in 1910. There were nine children in our family. I was sixteen years old. My parents had been able, with the help the six older children had given, to send them to college until they were practically finished or graduated.

I saw no opportunity to attend the Louisiana State University. The scholarship which I had won did not take into account books and living expenses. It would have been difficult to secure enough money.

I secured a position travelling for a large supply house which had a branch office in New Orleans. My job was to sell its products to the merchants and to advertise and solicit orders for it from house to house. Along with the work of soliciting orders from house to house and from merchants, I tacked up signs, distributed pie plates and cook books and occasionally held baking contests in various cities and towns.

In the summer of 1911, I secured employment with a packing company as a regular travelling salesman with a salary and expense account. For the first time in my life I felt that I had hit a bed of ease. I was permitted to stop at the best hotels of the day. My territory covered several states in the south. According to the lights and standards of my associates, I had arrived.

(2) Raymond Gram Swing, Good Evening (1964)

At that time, Senator Long was generally considered the buffoon of the American political stage. He was vulgar, ill-mannered, and amusingly impertinent. The man who plays the fool and is not counts on being underestimated and profiting from it. At the time I went to see Huey Long, the American public in general did not take him seriously. It knew virtually nothing about his accomplishments, his power, or his potentialities. The clergyman Smith, who gave up a wealthy pastorate to serve him, did. I think that at the time he genuinely believed that Long was a liberal and that as an editor of the Nation I would recognize it. What convinces me of this is that he vouched for me without reservation to Long, so that I was admitted to anything and everything I cared to attend, including a two-hour session he held with his county organizers in his bedroom.

This occasion was beyond doubt the most informal meeting of a political boss with his menials that one could hope to watch and listen to. The Kingfish, in green pajamas, stretched out on his bed part of the time, occasionally rubbing his itching toes, stood part of the time, hitching up his sagging nightwear, and on one occasion, in the midst of an outpouring of orders and comment, went to the open bathroom and urinated as he continued talking. The dozen or so local political leaders present spoke up to him freely, argued with him about local sentiment, and found that he knew their districts better than they did, and could tell them how to manage the upcoming election. If I had printed the dialogue I heard, it might well have convicted Huey Long of being a crooked politician. But that fact was not news in Louisiana, and if printed elsewhere about the Senate's leading buffoon, it would not have disturbed the country. The fact that the conversation was being held in my presence did not inhibit the party men; I was Huey's must And it did not inhibit Huey; I had been vouched for by Gerald Smith.

I attended two other sessions with his approval, one of a special meeting of the legislature in the skyscraper statehouse at Baton Rouge, the other of the Ways and Means Committee, both called to take care of thirty-five bills introduced by the Long machine. Long was at both meetings running things without the slightest right of membership. Nobody objected. This was Huey's legislature, his committee, his statehouse, his state. At the special session of the legislature, he answered questions from the floor. When one of the minority opposition objected to the speed with which the bills were read, he promised to have them printed before the meeting of tie Ways and Means Committee the following day. he was the only lively and articulate man in the room, waving his arms, grimacing with eves protruding, face flushed.

In the committee meeting at nine the next morning, Long read and explained each bill, then the chairman put it to a vote, smashing down his gavel. Here, too, he had no right to take part in the proceedings, but no one objected. The committee consisted of fifteen Long supporters and two oppositionists. Three bills were approved in the first six minutes, thirty-five were acted on in seventy minutes, all but one being approved. The rejected bill was one that Long scowled at when he looked at it, passed back to the chairman, and said: "We don't want that. Let them come to us," a remark which no one, explained. The bill was shelved.

This was dictatorship in the guise of the democratic process. And as the session proceeded, the dictatorship added to its power, grabbing patronage it did not yet control, gaining control over the appointment of schoolteachers, obtaining authority to remove the mayor in a town where Long had been showered with eggs, putting its grip on Baton Rouge, which he had failed to carry at the election, by gaining authority to name extra members to the local government board. It plastered an occupational tax on the refining of oil by Standard Oil, which Long had fought throughout his career. Subsequently, the company resisted by laying off a thousand workers. The workers held a protest meeting. Senator Long, threatened with revolt, rushed back from Washington, called out the militia, summoned the legislature in a special session, and struck a bargain with Standard Oil that he would remit sonic of the tax if Standard Oil would refine more Louisiana oil. He remitted four-fifths of the tax, which the legislature ratified. But the occupational tax was on the books to be used to gouge any business the Long machine cared to exploit or punish.

I confess that Huey Long puzzled me. How could the legislators - who looked like ordinarily decent men - put up with him, his blasphemous language, his unsavory conduct? They did not show fear of him; they seemed to like him. In his way, lie was their buddy - but a hundred times smarter than any of them. The dictators of Europe were explained as fulfilling the father-yearning in their peoples. Huey Long was no father image. He was a grown-up bad boy. The Rev. Gerald Smith undertook to explain the Long dictatorship. "It is," he told me, "the dictatorship of the surgical theater. The surgeon is in charge because he knows. Everyone defers to him for that reason only. The nurses and assistants do what lie tells them, asking no questions. They jump at his commands. They are not servile, they believe in the surgeon. They realize that he is working for the good of the patient."

This has to be said for Huey Long: he had strong liberal instincts and left to his credit a list of reforms not to be matched in any other Southern state. He shifted the burden of taxation from the poor to those who could afford to bear it. To finance his reforms, he increased the state's indebtedness from $11,000,000 to $150,000,000, but met each increase by new taxation. He passed legislation postponing the payment of private debt. He laid out a system of highways and bridges, and, above all, he dedicated himself to improving the state's education. He remodeled the school system to enable eight-month terms to be maintained in the poorest parishes and provided free textbooks. He strongly supported the Julius Rosenwald campaign against illiteracy, so that 100,000 adults in Louisiana, white and black, learned to read and write in his first term as governor. He backed Louisiana State University, assured it a good faculty, added a medical and dental school, and increased its enrollment from 1,500 to 4,000 in his first term as governor. As governor, he fought the public-utility companies and forced down power and telephone rates. He obtained a reduction of electricity rates in New Orleans. He built a five-million-dollar statehouse, an impressive high-tower building rising on the bank of the Mississippi.

Some of these are solid benefits, which attest that Huey Long knew the good he sought to accomplish. But I concluded that he wanted to do good because he knew it was the way to achieve power.

(3) Huey Long, speech in the Senate (29th April, 1932)

The great and grand dream of America that all men are created free and equal, endowed with the inalienable right of life and liberty and the pursuit of happiness - this great dream of America, this great light, and this great hope - has almost gone out of sight in this day and time, and everybody knows it; and there is a mere candle flicker here and yonder to take the place of what the great dream of America was supposed to be.

The people of this country have fought and have struggled, trying, by one process and the other, to bring about the change that would save the American country to the ideal and purposes of America. They are met with the Democratic Party at one time and the Republican Party at another time, and both of them at another time, and nothing can be squeezed through these party organizations that goes far enough to bring the American people to a condition where they have such a thing as a livable country. We swapped the tyrant 3,000 miles away for a handful of financial slaveowning overlords who make the tyrant of Great Britain seem mild.

Much talk is indulged in to the effect that the great fortunes of the United States are sacred, that they have been built up by the honest and individual initiative, that the funds were honorably acquired by men of genius far-visioned in thought. The fact that those fortunes have been acquired and that those who have built them for the financial masters have become impoverished is a sufficient proof that they have not been regularly and honorably acquired in this country.

Even if they had been that would not alter the case. I find that the Morgan and Rockefeller groups alone held, together, 341 directorships in 112 banks, railroad, insurance, and other corporations, and one of this group made an after-dinner speech in which he said that a newspaper report had asserted that 12 men in the United States controlled the business of the Nation, and in the same speech to this group he said, "And I am one of the 12 and you the balance, and this statement is correct."

They pass laws under which people may be put in jail for utterances made in war times and other times, but you can not stifle or keep from growing, as poverty and starvation and hunger increase in this country, the spirit of the American people, if there is going to be any spirit in America at all.

Unless we provide for the redistribution of wealth in this country, the country is doomed; there is going to be no country left here very long. That may sound a little bit extravagant, but I tell you that we are not going to have this good little America here long if we do not take to redistribute the wealth of this country.

(4) Hermann Deutsch wrote about Huey P. Long and his campaign for Hattie Caraway in an article he wrote for the Saturday Evening Post on 15th October, 1932.

Farmers drove to town in their own automobiles - and no few of the cars were this year's models - in such numbers that highways were congested in every direction. Fifteen minutes after he began to talk, Huey Long would have these same farmers convinced that they were starving and would have to boil their old boots and discarded tires to have something to feed the babies till the Red Cross brought around a sack of meal and a bushel of sweet potatoes to tide them over; that Wall Street's control of the leaders - not the rank and file - of both Democratic and Republican parties was directly responsible for this awful condition; that the only road to salvation lay in the reelection of Hattie W. Caraway to the Senate.

(5) Huey P. Long, Share Our Wealth pamphlet (1934)

For 20 years I have been in the battle to provide that, so long as America has, or can produce, an abundance of the things which make life comfortable and happy, that none should own so much of the things which he does not need and cannot use as to deprive the balance of the people of a reasonable proportion of the necessities and conveniences of life. The whole line of my political thought has always been that America must face the time when the whole country would shoulder the obligation which it owes to every child born on earth - that is, a fair chance to life, liberty, and happiness.

Here is what I ask the officers and members and well-wishers of all the Share Our Wealth Societies to do:

First. If you have a Share Our Wealth Society in your neighborhood or, if you have not one, organize one - meet regularly, and let all members, men and women, go to work as quickly and as hard as they can to get every person in the neighborhood to become a member and to go out with them to get more members for the society. If members do not want to go into the society already organized in their community, let them organize another society. We must have them as members in the movement, so that, by having their cooperation, on short notice we can all act as one person for the one object and purpose of providing that in the land of plenty there shall be comfort for all. The organized 600 families who control the wealth of America have been able to keep the 125,000,000 people in bondage because they have never once known how to effectually strike for their fair demands.

Second. Get a number of members of the Share Our Wealth Society to immediately go into all other neighborhoods of your county and into the neighborhoods of the adjoining counties, so as to get the people in the other communities and in the other counties to organize more Share Our Wealth Societies there; that will mean we can soon get about the work of perfecting a complete, unified organization that will not only hear promises but will compel the fulfillment of pledges made to the people.

It is impossible for the United States to preserve itself as a republic or as a democracy when 600 families own more of this Nation's wealth - in fact, twice as much - as all the balance of the people put together. Ninety-six percent of our people live below the poverty line, while 4 percent own 87 percent of the wealth. America can have enough for all to live in comfort and still permit millionaires to own more than they can ever spend and to have more than they can ever use; but America cannot allow the multimillionaires and the billionaires, a mere handful of them, to own everything unless we are willing to inflict starvation upon 125,000,000 people.

Here is the whole sum and substance of the share-our-wealth movement:

1. Every family to be furnished by the Government a homestead allowance, free of debt, of not less than one-third the average family wealth of the country, which means, at the lowest, that every family shall have the reasonable comforts of life up to a value of from $5,000 to $6,000. No person to have a fortune of more than 100 to 300 times the average family fortune, which means that the limit to fortunes is between $1,500,000 and $5,000,000, with annual capital-levy, taxes imposed on all above $1,000,000.

2. The yearly income of every family shall be not less than one-third of the average family Income, which means that, according to the estimates of the statisticians of the United States Government and Wall Street, no family's annual income would be less than from $2,000 to $2,500. No yearly income shall be allowed to any person larger than from 100 to 300 times the size of the average family income, which means; that no person would be allowed to earn in any year more than from $600,000 to $1,800,000, all to be subject to present income-tax laws.

3. To limit or regulate the hours of work to such an extent as to prevent overproduction; the most modern and efficient machinery would be encouraged, so that as much would be produced as possible so as to satisfy all demands of the people, but to also allow the maximum time to the workers for recreation, convenience, education, and luxuries of life.

4. An old-age pension to the persons of 60.

5. To balance agricultural production with what can be consumed according to the laws of God, which includes the preserving and storage of surplus commodities to be paid for and held by the Government for the emergencies when such are needed. Please bear in mind, however, that when the people of America have had money to buy things they needed, we have never had a surplus of any commodity. This plan of God does not call for destroying any of the things raised to eat or wear, nor does it countenance wholesale destruction of hogs, cattle, or milk.

6. To pay the veterans of our wars what we owe them and to care for their disabled.

7. Education and training for all children to be equal in opportunity in all schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions for training in the professions and vocations of life; to be regulated on the capacity of children to learn, and not on the ability of parents to pay the costs. Training for life's work to be as much universal and thorough for all walks in life as has been the training in the arts of killing.

8. The raising of revenue and taxes for the support of this program to come from the reduction of swollen fortunes from the top, as well as for the support of public works to give employment whenever there may be any slackening necessary in private enterprise.

(6) Gerald L. K. Smith, New Republic (13th February, 1935)

Huey Long is the greatest headline writer I have ever seen. His circulars attract, bite, sting and convince. It is difficult to imagine what would happen in America if every human being were to read one Huey Long circular on the same day. As a mass-meeting speaker, his equal has never been known in America. His knowledge of national' and international affairs, as well as local affairs, is uncanny. He seems to be equally at home with all subjects, such as shipping, railroads, banking, Biblical literature, psychology, merchandising, utilities, sports. Oriental affairs, international treaties. South American affairs, world history, the Constitution of the United States, the Napoleonic Code, construction, higher education, flood control, cotton, lumber, sugar, rice, alphabetical relief agencies. Besides this, I am convinced that he is the greatest political strategist alive. Huey Long is a superman. I actually believe that he can do as much in one day as any ten men I know. He abstains from alcohol, he uses no tobacco; he is strong, youthful and enthusiastic. Hostile communities and individuals move toward him like an avalanche once they see him and hear him speak. His greatest recommendation is that we who know him best, love him most.

(7) Raymond Gram Swing, The Nation (January, 1935)

He is not a fascist, with a philosophy of the state and its function in expressing the individual. He is plain dictator. He rules, and opponents had better stay out of his way. He punishes all who thwart him with grim, relentless, efficient vengeance.

But to say this does not make him wholly intelligible. One does not understand the problem of Huey Long or measure the menace he represents to American democracy until one admits that he has done a vast amount of good for Louisiana. He has this to justify all that is corrupt and peremptory in his methods. Taken all in all, I do not know any man who has accomplished so much that I approve of in one state in four years, at the same time that he has done so much that I dislike. It is a thoroughly perplexing, paradoxical record.

If he were to die today, and the fear and hatred of him died too, and an honest group of politicians came into control of Louisiana, they would find a great deal to thank Huey Long for. He has reshaped the organism of an archaic state government, centralized it, made it easy to operate efficiently. Most important of all, he has shifted the weight of taxation from the poor, who were crippled under it, to the shoulders that can bear it.

Huey Long is the best stump speaker in America. He is the best political radio speaker, better even than President Roosevelt. Give him time on the air and let him have a week to campaign in each state, and he can sweep the country. He is one of the most persuasive men living." This is the opinion not of a Long supporter, but of one of the key men in the fight against the Kingfish in Louisiana. The North, he said, is misled into dismissing him as a clown, and has no conception of Huey's talents and of his almost invincible mass appeal. Mrs. Hattie Caraway of Arkansas can testify to his powers, for when she entered the primary asking to succeed her late husband in the United States Senate, she was generally expected to run last among five candidates and to poll not more than 2, 000 votes. The four men against her were experienced and able. But Huey took his sound van into Arkansas for one week, and though he could not get into every county, he made a circular tour during which he spoke six times a day. Instead of 2,000 votes Mrs. Caraway won a majority over the combined opposition in the first primary, tantamount to election in a Democratic state. An analysis of the vote showed that the districts where Huey did not appear virtually ignored her, while those which he toured gave her a landslide.

When his hour strikes, Huey will attack the rest of America with the same vehemence. That probably will be during the campaign of 1936. His platform will be the capital levy, strangely enough his exclusive possession as a political theme. He will speak more violently than Father Coughlin against the money interests of Wall Street and against the evil of large fortunes. He will pose as a misunderstood man, and to most listeners he will give their first information of what he has accomplished in Louisiana. He will be direct, picturesque, and amusing, a relief after the attenuated vagueness of most of the national speaking today. He will promise a nest egg of $5,000 for every deserving family in America, this to be the minimum of poverty in his brave new world. He rashly will undertake to put all the employables to work in a few months. He will assail President Roosevelt with a passion which may at first offend listeners, but in the end he might stir up opposition of a bitterness the President has not tasted in his life. Obviously, he cannot succeed while the country still has hopes of the success of the New Deal and trusts the President. Huey's chances depend on those sands of hope and trust running out. He is no menace if the President produces reform and recovery. But if in two years, even six, misery and fear are not abated in America the field is free to the same kind of promise-mongers who swept away Democratic leaders in Italy and Germany. Huey believes Roosevelt can be beaten as early as 1936, but he is prepared to agitate for another four years. In 1940 he will still be a young man of forty-six.

Huey Long publishes his own newspaper, but in Louisiana he depends still more on a remarkable system of circulars. His card catalogue of local addresses is the most complete of any political machine in the world. It holds the name of every Long man in every community in the state, and tells just how many circulars this man will undertake personally to distribute to neighbors. Huey's secretary maintains a pretentious multigraph office, and it can run off the circulars and address envelopes to each worker in a single evening. Huey then mobilizes all the motor vehicles of the state highway department and the highway police. The circulars can leave New Orleans at night and be in virtually every household in the state by morning.

One may say that remarkable as that may be, it will work only in Louisiana and cannot be done throughout the United States. But in a way it can. By November the "Share Our Wealth" campaign had recruited 3,687,'641 members throughout the country in eight months. (The population of Louisiana is only 2,000,000.) Every member belongs to a society, and Huey has the addresses of those who organized it. To them can go circulars enough for all members. The "Share Our Wealth" organization is first of all a glorified mailing list, already one of the largest in the land, but certain to grow much larger once the Long campaign gets under way. It is the nucleus of a nation-wide political machine. And though the movement is naively simple, its very simplicity is one secret of its success. Anyone can form a society. Its members pay no dues. They send an address to Huey and he supplies them with his literature, including a copy of his autobiography. He urges societies to meet and discuss the redistribution of wealth and the rest of his platform. He promises to furnish answers and arguments needed to silence critics.

I doubt whether Huey and the Reverend Gerald L. K. Smith realize that property as such cannot be redistributed. How, for instance, divide a factory or a railroad among families? Value lies in use, and if the scheme were to be realized, all property would have to be nationalized, and the income from use distributed. The income from $5,000 would not be much for each family, not more than $200 or $300, certainly not enough to make true the dream of a home free of debt, a motor car, an electric refrigerator, and a college education for all the children, which is Huey's way of picturing his millennium. And if property is to be nationalized, why not share it equally? Why give the poor only a third, and decree the scramble for the other two-thirds in the name of capitalism? If Huey were to ask himself this question, he probably would answer that since both he and America believe in capitalism, he must advocate it. But probably he has not thought the platform through. He conceived of it early one morning, summoned his secretary, and had the organization worked out before noon of the same day. It isn't meant to be specific. It is only to convey to the unhappy people that he believes in a new social order in which the minimum of poverty is drastically raised, the rich somehow to foot the bill through a capital levy. It may be as simple as a box of kindergarten blocks, but could he win mass votes, or organize nearly four million people in eight months, by distributing a primer of economics?

(8) Huey P. Long, radio broadcast (14th January, 1935)

God invited us all to come and eat and drink all we wanted. He smiled on our land and we grew crops of plenty to eat and wear. He showed us in the earth the iron and other things to make everything we wanted. He unfolded to us the secrets of science so that our work might be easy. God called: "Come to my feast." But what had happened? Rockefeller, Morgan, and their crowd stepped up and took enough for 120,000,000 people and left only enough for 5,000,000 for all the other 125,000,000 to eat. And so many millions must go hungry and without these good things God gave us unless we call on them to put some of it back.

(9) Roy Wilkins interviewed Huey P. Long for The Crisis in February, 1935.

"How about lynching. Senator? About the Costigan-Wagner bill in congress and that lynching down there yesterday in Franklinton..."

He ducked the Costigan-Wagner bill, but of course, everyone knows he is against it. He cut me off on the Franklinton lynching and hastened in with his "pat" explanation:

"You mean down in Washington parish (county)? Oh, that? That one slipped up on us. Too bad, but those slips will happen. You know while I was governor there were no lynchings and since this man (Governor Allen) has been in he hasn't had any. (There have been 7 lynchings in Louisiana in the last two years.) This one slipped up. I can't do nothing about it. No sir. Can't do the dead nigra no good. Why, if I tried to go after those lynchers it might cause a hundred more niggers to be killed. You wouldn't want that, would you?"

"But you control Louisiana," I persisted, "you could..."

"Yeah, but it's not that simple. I told you there are some things even Huey Long can't get away with. We'll just have to watch out for the next one. Anyway that nigger was guilty of coldblooded murder."

"But your own supreme court had just granted him a new trial."

"Sure we got a law which allows a reversal on technical points. This nigger got hold of a smart lawyer somewhere and proved a technicality. He was guilty as hell. But we'll catch the next lynching."

My guess is that Huey is a hard, ambitious, practical politician. He is far shrewder than he is given credit for being. My further guess is that he wouldn't hesitate to throw Negroes to the wolves if it became necessary; neither would he hesitate to carry them along if the good they did him was greater than the harm. He will walk a tight rope and go along

as far as he can. He told New York newspapermen he welcomed Negroes in the share-the-wealth clubs in the North where they could vote, but down South? Down South they can't vote: they are no good to him. So he lets them strictly alone. After all, Huey comes first.

Anyway, menace or benefactor, he is the most colorful character I have interviewed in the twelve years I've been in the business.

(10) Hodding Carter, The American Mercury (April, 1949)

In the spring of 1932 I turned from reporting to start a small daily newspaper in Hammond, Louisiana. By then, Huey Long was immovably established as Louisiana's junior Senator in Washington and Louisiana's Kingfish at home. From the first issue of our newspaper I editorially criticized his tightening grip upon the state and the corruption which accompanied it. The initial reaction of his district lieutenants was a fairly mild annoyance. Ours was a puny, insecure newspaper. Doubtless it would welcome help. A man whom I had known since childhood, a friend of my family, came to me with the suggestion that I get right. Surely I needed better equipment for my newspaper, and better equipment could be procured for the friends of the administration. There were constitutional amendments to be printed, political advertising, security permanence. Just get right.

Later the approach was to change. I still have the threatening, unsigned letters. Get out of town, you lying bastard, if you know what's good for you. Intermittently, for four years, I received threats by letter and telephone, and twice in person. I carried a pistol, I kept it in my desk during the day and by my bed at night.

(11) James Farley ran Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidential campaigns in 1932 and 1936. He wrote about the dangers posed by Huey P. Long in Behind the Ballots (1938)

I've always made an effort not to let personal bias warp my political judgment. We kept a careful eye on what Huey and his political allies, both in office and out of office, were attempting to do. Anxious not to be caught napping and desiring an accurate picture of conditions, the Democratic National Committee conducted a secret poll on a national scale during this period to find out if Huey's sales talks for his "share the wealth" program were attracting many customers. The result of that poll, which was kept secret and shown only to a very few people, was surprising in many ways. It indicated that, running on a third-party ticket. Long would be able to poll between 3,000,000 to 4,000,000 votes for the Presidency. The poll demonstrated also that Huey was doing fairly well at making himself a national figure. His probable support was not confined to Louisiana and nearby states. On the contrary, he had about as much following in the North as in the South, and he had as strong an appeal in the industrial centers as he did in the rural areas. Even the rock-ribbed Republican state of Maine, where the voters were steeped in conservatism, was ready to contribute to Long's total vote in about the same percentage as other states.

While we realized that polls are often inaccurate and that conditions could change perceptibly before the election actually took place, the size of the Long vote made him a formidable factor. He was head and shoulders stronger than any of the other "Messiahs" who were also gazing wistfully at the White House and wondering what chance they would have to arrive there as the result of a popular uprising. It was easy to conceive a situation whereby Long, by polling more than 3,000,000 votes, might have the balance of power in the 1936 election. For example, the poll indicated that he would command upward of 100,000 votes in New York State, a pivotal state in any national election; and a vote of that size could easily mean the difference between victory or defeat for the Democratic or Republican candidate. Take that number of votes away from either major candidate, and they would come mostly from our side, and the result might spell disaster.

(12) Raymond Moley, After Seven Years (1939)

I spent many hours talking with Huey Long in the three years before his death. When we talked about politics, public policies, and life generally, he cast off the manner of a demagogue as an actor wipes off greasepaint. There could be no question about his extraordinary mental - or, if you will, intellectual - capacity. I have never known a mind that moved with more clarity, decisiveness, and force. He was no backwoods buffoon, although when the occasion seemed to offer profit by such a role he could outrant a Heflin or a Bilbo. But the state of Louisiana reveals ample evidence of his immense contributions to the happiness and welfare of its people. As his power in that state grew to be secure and absolute, the virus of success took hold. There can be no doubt of his purposes: first, the complete consolidation of his power in Louisiana; second, his use of his forum in the Senate to grasp national attention; and, finally, to direct a campaign of national "education" through the states toward a Presidential nomination for himself at some future time.

(13) John T. Flynn, The Roosevelt Myth (1944)

After a tempestuous career as governor of Louisiana, Long was elected to the Senate and, before he took his seat, played a decisive role at a critical moment in the nomination of Roosevelt. Fearing neither God nor man nor the devil, he was not intimidated by the White House or the Senate. At his first meeting with Roosevelt in the White House, he stood over the President with his hat on and emphasized his points with an occasional finger poked into the executive chest. He found very quickly that he could move as brusquely around the Senate floor as he had the lobbies of the state legislature. He strode about the Capitol followed by his bodyguards. He ranted on the Senate floor. He made a fifteenhour oneman filibustering speech. He made up his mind very soon that the New Deal was a lot of claptrap and proceeded to preach his own gospel of the abundant life.

He cried out: "Distribute our wealth it's all there in God's book. Follow the Lord." This was the prelude to his SharetheWealth crusade. Huey proclaimed "Every man a King" with Huey as the Kingfish. He made it plain he was no Communist despoiler. He assured Rockefeller he was not going to take all his millions. He would not take a single luxury from the economic royalists. They would retain their "fish ponds, their estates and their horses for riding to the hounds."

When he began, he had no plan at all. He just had a slogan and worked up from there. But by 1934 he was ready to launch the movement with Gerald L. K. Smith, a former Shreveport preacher, at its head. The program was simple. No income would exceed a million dollars. Everybody would have a minimum income of $2500. The money would be provided by a capital levy which would remove the surplus millions from the rich which revealed that Huey really did not know any more about economics than the President did. There would, of course, be oldage pensions for all, free education right through college for all, an electric refrigerator and an automobile for every family. The government would buy up all the agricultural surpluses against the day of shortages. As a matter of course, there would be short working hours for everyone, and bonuses for veterans. All surplus property would be turned over to the government so that a fellow who needed a bed would get one from the fellow who owned more than one.

Some editors who supported Roosevelt said Huey's plan was "like the weird dream of a plantation darky." It is not clear why Huey broke with Roosevelt. It is probably because it was impossible for him to endure the role of second fiddle to any man and he had come to see wider horizons for his own strange talents. Visitors to the Capitol were more eager to have the guides point out Huey Long than any other exhibit in the building. He was aware of the immense notoriety he had achieved and he believed he saw a condition approaching in which he could repeat upon the national scene the amazing performance he had given in Louisiana.

Roosevelt went to work in Louisiana on the rebel Kingfish. He poured money into the hands of Huey's enemies to disburse to Huey's loyal Cajuns. And there came a moment when Huey seemed to be on his way to the doghouse. But he was an incorrigible figure of unconquerable energy. When Roosevelt sought to buy with federal funds the Louisiana electorate and ring, Huey struck back with a series of breathtaking blows that brought the state under his thumb almost as completely as Hitler's Reich under the heel of the Fuehrer. First of all, he stopped federal funds from entering Louisiana. He forced the legislature to pass a law forbidding any state of local board or official from incurring any debt or receiving any federal funds without consent of a central state board. And this board Huey set up and dominated. He cut short an estimated flood of $30,000,000 in PWA projects. Then he provided, through state operations and borrowing, a succession of public works, roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, farm projects and relief measures. The money was spent to boost Huey instead of Roosevelt. The people were taught to thank and extol Huey rather than Roosevelt for all these goods.

He gave the people tax exemptions, ended the poll tax, cut automobile taxes, put heavier taxes on utilities and corporations. He took over the police department of New Orleans from the City Ring, threw out their police commissioners. He was followed around by troops. He gathered into his hands through his personally owned governor absolute control over every state and parish office. He got control of education and the teachers. He took over the State University and added its football team and its hundredpiece band to the noisy and glittering hippodrome in which he exploited himself. He possessed the entire apparatus of government in Louisiana the schools, the treasury, the public buildings and the men and women in the buildings. He owned most of the courts, and had a secret police of his own. He ran the elections, counted the votes and held in his hands the power of life and death over most of the enterprise in the state.

(14) John Fournet witnessed the shooting of Huey Long. He was interviewed about the incident in a television documentary, Huey Long, that was made in 1985.

As he emerged there, all of a sudden, I saw a strange look in his face and at the same time I had a Panama hat in my left hand - and I saw a little gun go right close to me, within a foot or two, a black gun, automatic, and about simultaneously one of the so-called bodyguards, young fellow by the name of Murphy Roden, grabbed the gun and it went off simultaneously, because it hit Huey on the right side - so went along here and through the small of the back, you see, downward.

After a while, after they had a coroner's inquest and the man was found riddled with 59 bullets in his body, they came and knocked on the door (at the hospital) and I said: "You can't come in" and he said: "I just want to tell Huey who shot him". And Huey, loud as ever: "Let him in" - he had a big, strong voice - and of course I had to let him in. He told him a young doctor by the name of Carl Weiss had shot him. "Well," he says. "What does he want to shoot me for?"

(15) A Louisiana journalist was in the Senate building when Huey Long was shot. He was interviewed about the incident in a documentary, Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?, that was made in 1975.

Twenty years of newspaper experience failed to prepare me for the tragedy I witnessed Sunday night. I was coming out of Governor Allen's office when I heard a shot. Outside in the hall I saw Senator Long stagger away, grasping his side with his right hand. Half a dozen members of the senator's guard joined the shooting and the man who had shot Senator

Long pitched forward dead from 30 or 40 bullets. The hallway was filled with smoke. Senator Long meanwhile walked down the hall, descended the stairway, was aided into an automobile and taken to the nearby Lady of the Lakes sanatorium where he died 30 hours later.

(16) Huey P. Long, obituary, New York Times (11th September, 1935)

Of Huey Long personally it is no longer necessary to speak except with charity. His motives, his character, have passed beyond human judgment. People will long talk of his picturesque career and extraordinary individual qualities. He carried daring to the point of audacity. He did not hesitate to flaunt his great personal vainglory in public. This he would probably have defended both as a form of self-confidence, and a means of impressing the public. He had a knack of always getting into the picture, and often bursting out of its frame. There would be no end if one were to try to enumerate all his traits, so distinct and so full of color. He succeeded in establishing a legend about himself - a legend of invincibility - which it will be hard to dissipate.

It is to Senator Long as a public man, rather than as a dashing personality, that the thoughts of Americans should chiefly turn as his tragic death extinguishe the envy. What he did and what he promised to do are full of political instruction and also of warning. In his own State of Louisiana he showed how it is possible to destroy self-government while maintaining its ostensible and legal form. He made himself an unquestioned dictator, though a State Legislature was still elected by a nominally free people, as was also a Governor, who was, however, nothing but a dummy for Huey Long. In reality. Senator Long set up a Fascist government in Louisiana. It was disguised, but only thinly. There was no outward appearance of a revolution, no march of Black Shirts upon Baton Rouge, but the effectual result was to lodge all the power of the State in the hands of one man.

If Fascism ever comes in the United States it will come in something like that way. No one will set himself up as an avowed dictator, but if he can succeed in dictating everything, the name does not matter. Laws and Constitutions guaranteeing liberty and individual rights may remain on the statute books, but the life will have gone out of them. Institutions may be designated as before, but they will have become only empty shells. We thus have an indication of the points at which American vigilance must be eternal if it desires to withstand the subtle inroads of the Fascist spirit. There is no need to be on the watch for a revolutionary leader to rise up and call upon his followers to march on Washington. No such sinister figure is likely to appear. The danger is, as Senator Long demonstrated in Louisiana, that freedom may be done away with in the name of efficiency and a strong paternal government.

Senator Long's career is also a reminder that material for the agitator and the demagogue is always ample in this country. He found it and played upon it skillfully, first of all in what may be called the lower levels of society in Louisiana. Afterward, when he began to swell with national ambition, and cast about for a fetching cry, he found it, or thought he did, in his vague formulas, never worked out, about the "distribution of wealth." For a time he seemed in this way to be about to fascinate and capture a great multitude of followers, or at least endorsers, mainly in the cities of this country. There is reason to believe that his hold upon them was relaxing before his assassination. Many observers thought that he had already passed the peak of his national influence. Be that as it may, the moral of his remarkable adventure in politics

remains the same. It is that in the United States we have to re-educate each generation in the fundamentals of self government and in the principles of sound finance. And we must have leaders able to defend the faith that is in them. When such masses of people are all too ready to run after a professed miracle-worker, it is essential that we have trained minds to confront the ignorant, to show to the credulous the error of their ways, and to keep alive and fresh the true tradition of democracy in which this country was cradled and brought to maturity.

(17) Senator William Langer of North Dakota, speech (1941)

I doubt whether any other man was so conscious of the plight of the underprivileged or knew better the ruthlessness of those in control. And it was because Huey Long knew how to fight, knew how to fight fire with fire, knew how to combat ruthlessness with ruthlessness, force with force, and because he had the courage to battle unceasingly for what he conceived to be right that he became an inspiration for so many in their own fight for a square deal, and the object of such relentless persecution on the part of his enemies.

The fight he waged was such a desperate one that even in death he has not been immune from attack. So we find that 5 years after his body had been lowered into the grave - that grave which will forever be a shrine for those who love decency, honor, and justice - attempts are still being made to besmirch his character.

This is not fooling the farmer, the worker, the small businessman; it is not fooling the child who can read today because of the free textbooks that Huey Long obtained; it is not fooling the citizen who can vote today because Huey Long abolished poll taxes.

These people know from Huey Long's life that, as they fight for the better things, there will always be the inspiration that fighting with them in spirit will be that tearless, dauntless, unmatchable champion of the common people, Huey P. Long.