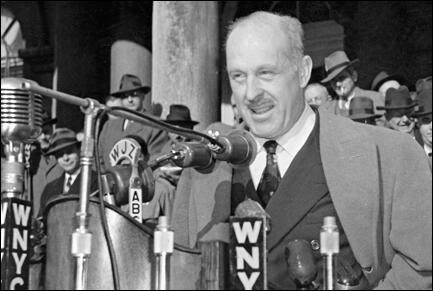

Drew Pearson

Drew Pearson was born in Evanston, Illinois, on 13th December, 1897. In 1902 the family moved to Pennsylvania, where his father, Paul Pearson, became professor of public speaking at Swarthmore College.

Pearson was educated at the Phillips Exeter Academy and Swarthmore College, where he edited the student newspaper, The Phoenix. In 1919 Pearson, a Quaker, travelled to Serbia where he spent two years rebuilding houses that had been destroyed during the First World War.

After returning to America, Drew taught industrial geography at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1923 he embarked on a worldwide tour visiting Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand and India. He paid for his trip by writing articles for an American newspaper syndicate. Pearson taught briefly at Columbia University before returning to journalism and reporting on anti-foreigner demonstrations in China (1927), the Geneva Naval Conference (1928) and the Pan American Conference in Cuba (1928). In 1929 Pearson became Washington correspondent of the Baltimore Sun. Three years later he joined the Scripps-Howard syndicate, United Features. His Merry-Go-Round column was published in newspapers all over the United States.

Pearson was a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal program. He also upset more conservative editors when he advocated United States involvement in the struggle against fascism in Europe. Pearson's articles were often censored and so in 1941 he switched to the more liberal The Washington Post.

Pearson was a close friend of Ernest Cuneo, a senior figure in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Cuneo leaked several stories to Pearson including one concerning General George S. Patton. On 3rd August 1943, he visited the 15th Evacuation Hospital where he encountered Private Charles H. Kuhl, who had been admitted suffering from shellshock. When Patton asked him why he had been admitted, Kuhl told him "I guess I can't take it." According to one eyewitness Patton "slapped his face with a glove, raised him to his feet by the collar of his shirt and pushed him out of the tent with a kick in the rear." Kuhl was later to claim that he thought Patton, as well as himself, was suffering from combat fatigue.

Two days after the incident he sent a memo to all commanders in the 7th Army: "It has come to my attention that a very small number of soldiers are going to the hospital on the pretext that they are nervously incapable of combat. Such men are cowards and bring discredit on the army and disgrace to their comrades, whom they heartlessly leave to endure the dangers of battle while they, themselves, use the hospital as a means of escape. You will take measures to see that such cases are not sent to the hospital but are dealt with in their units. Those who are not willing to fight will be tried by court-martial for cowardice in the face of the enemy."

On 10th August 1943, Patton visited the 93rd Evacuation Hospital to see if there were any soldiers claiming to be suffering from combat fatigue. He found Private Paul G. Bennett, an artilleryman with the 13th Field Artillery Brigade. When asked what the problem was, Bennett replied, "It's my nerves, I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton exploded: "Your nerves. Hell, you are just a goddamned coward, you yellow son of a bitch. Shut up that goddamned crying. I won't have these brave men here who have been shot seeing a yellow bastard sitting here crying. You're a disgrace to the Army and you're going back to the front to fight, although that's too good for you. You ought to be lined up against a wall and shot. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself right now, God damn you!" With this Patton pulled his pistol from its holster and waved it in front of Bennett's face. After putting his pistol way he hit the man twice in the head with his fist. The hospital commander, Colonel Donald E. Currier, then intervened and got in between the two men.

Colonel Richard T. Arnest, the man's doctor, sent a report of the incident to General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The story was also passed to the four newsmen attached to the Seventh Army. Although Patton had committed a court-martial offence by striking an enlisted man, the reporters agreed not to publish the story. Quentin Reynolds of Collier's Weekly agreed to keep quiet but argued that there were "at least 50,000 American soldiers on Sicily who would shoot Patton if they had the chance."

Eisenhower now had a meeting with the war correspondents who knew about the incident and told them that he hoped they would keep the "matter quiet in the interests of retaining a commander whose leadership he considered vital." Ernest Cuneo, who was fully aware, now decided to pass this story to Pearson and in November 1943, he told the story on his weekly syndicated radio program. Some politicians demanded that George S. Patton should be sacked but General George Marshall and Henry L. Stimson supported Eisenhower in the way he had dealt with the case.

During the Second World War Pearson created a great deal of controversy when he took up the case of John Gates, a member of the American Communist Party, who was not allowed to take part in the D-Day landings. Gates later pointed out: "Newspaper columnist Drew Pearson published an account of my case... Syndicated coast-to-coast, the column meant well but it contained all kinds of unauthorized, secret military information - the name of my battalion, the fact that it had been alerted for overseas, my letter to the President and his reply, and the officers' affidavits. As a result of this violation of military secrecy, the date for the outfit going overseas was postponed, the order restoring me to my battalion was countermanded and I was out of it for good. It seems that some of my friends, a bit overzealous in my cause, had given Pearson all this information, thinking the publicity would do me good."

Pearson also became a radio broadcaster. He soon became one of America's most popular radio personalities. After the war he was an enthusiastic supporter of the United Nations and helped to organize the Friendship Train project in 1947. The train travelled coast-to-coast collecting gifts of food for those people in Europe still suffering from the consequences of the war.

In 1947 Pearson recruited Jack Anderson as his assistant. Over the next few years Anderson was able to use his contacts that he had developed in the Office of Strategic Services(OSS) in China during the Second World War. This included John K. Singlaub, Ray S. Cline, Richard Helms, E. Howard Hunt, Mitchell WerBell, Paul Helliwell, Robert Emmett Johnson and Lucien Conein. Others working in China at that time included Tommy Corcoran, Whiting Willauer and William Pawley.

One of Anderson's first stories concerned the dispute between Howard Hughes, the owner of Trans World Airlines and Owen Brewster, chairman of the Senate War Investigating Committee. Hughes claimed that Brewster was being paid by Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) to persuade the United States government to set up an official worldwide monopoly under its control. Part of this plan was to force all existing American carriers with overseas operations to close down or merge with Pan Am. As the owner of Trans World Airlines, Hughes posed a serious threat to this plan. Hughes claimed that Brewster had approached him and suggested he merge Trans World with Pan Am. Pearson and Anderson began a campaign against Brewster. They reported that Pan Am had provided Bewster with free flights to Hobe Sound, Florida, where he stayed free of charge at the holiday home of Pan Am Vice President Sam Pryor. As a result of this campaign Bewster lost his seat in Congress.

In the late 1940s Anderson became friendly with Joseph McCarthy. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, "Joe McCarthy... was a pal of mine, irresponsible to be sure, but a fellow bachelor of vast amiability and an excellent source of inside dope on the Hill." McCarthy began supplying Anderson with stories about suspected communists in government. Pearson refused to publish these stories as he was very suspicious of the motives of people like McCarthy. In fact, in 1948, Pearson began investigating J. Parnell Thomas, the Chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. It was not long before Thomas' secretary, Helen Campbell, began providing information about his illegal activities. On 4th August, 1948, Pearson published the story that Thomas had been putting friends on his congressional payroll. They did no work but in return shared their salaries with Thomas.

Called before a grand jury, J. Parnell Thomas availed himself to the 5th Amendment, a strategy that he had been unwilling to accept when dealing with the Hollywood Ten. Indicted on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, Thomas was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months in prison and forced to pay a $10,000 fine. Two of his fellow inmates in Danbury Federal Correctional Institution were Lester Cole and Ring Lardner Jr. who were serving terms as a result of refusing to testify in front of Thomas and the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1949 Pearson criticised the Secretary of Defence, James Forrestal, for his conservative views on foreign policy. He told Jack Andersonthat he believed Forrestal was "the most dangerous man in America" and claimed that if he was not removed from office he would "cause another world war". Pearson also suggested that Forrestal was guilty of corruption. Pearson was blamed when Forrestal committed suicide on 22nd May 1949. One journalist, Westbrook Pegler, wrote: "For months, Drew Pearson... hounded Jim Forrestal with dirty aspersions and insinuations, until, at last, exhausted and his nerves unstrung, one of the finest servants that the Republic ever had died of suicide." On 23nd May, 1949, Pearson wrote in his diary that "Pegler had published a column virtually accusing me of murdering Forrestal." The following day he wrote: "Late this afternoon I clapped a libel suit of $250,000 on Pegler". The case was eventually settled out of court.

Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson also began investigating General Douglas MacArthur. In December, 1949, Anderson got hold of a top-secret cable from MacArthur to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, expressing his disagreement with President Harry S. Truman concerning Chaing Kai-shek. On 22nd December, 1949, Pearson published the story that: "General MacArthur has sent a triple-urgent cable urging that Formosa be occupied by U.S. troops." Pearson argued that MacArthur was "trying to dictate U.S. foreign policy in the Far East".

Harry S. Truman and Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, told MacArthur to limit the war to Korea. MacArthur disagreed, favoring an attack on Chinese forces. Unwilling to accept the views of Truman and Dean Acheson, MacArthur began to make inflammatory statements indicating his disagreements with the United States government.

MacArthur gained support from right-wing members of the Senate such as Joe McCarthy who led the attack on Truman's administration: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, 'Now let's be calm, let's do nothing'. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murders."

On 7th October, 1950, Douglas MacArthur launched an invasion of North Korea by the end of the month had reached the Yalu River, close to the frontier of China. On 20th November, Pearson wrote in his column that the Chinese were following a strategy that was "sucking our troops into a trap." Three days later the Chinese Army launched an attack on MacArthur's army. North Korean forces took Seoul in January 1951. Two months later, Harry S. Truman removed MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea.

Joe McCarthy continued to provide Jack Anderson with a lot of information. In his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, Anderson pointed out: "At my prompting he (McCarthy) would phone fellow senators to ask what had transpired this morning behind closed doors or what strategy was planned for the morrow. While I listened in on an extension he would pump even a Robert Taft or a William Knowland with the handwritten questions I passed him."

In return, Anderson provided McCarthy with information about politicians and state officials he suspected of being "communists". Anderson later recalled that his decision to work with McCarthy "was almost automatic.. for one thing, I owed him; for another, he might be able to flesh out some of our inconclusive material, and if so, I would no doubt get the scoop." As a result Anderson passed on his file on the presidential aide, David Demarest Lloyd.

On 9th February, 1950, Joe McCarthy made a speech in Salt Lake City where he attacked Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, as "a pompous diplomat in striped pants". He claimed that he had a list of 57 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party. McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. As it happens, if McCarthy had been screened, his own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list.

Pearson immediately launched an attack on Joe McCarthy. He pointed out that only three people on the list were State Department officials. He added that when this list was first published four years ago, Gustavo Duran and Mary Jane Keeney had both resigned from the State Department (1946). He added that the third person, John S. Service, had been cleared after a prolonged and careful investigation. Pearson also argued that none of these people had been named were members of the American Communist Party.

Jack Anderson asked Pearson to stop attacking McCarthy: "He is our best source on the Hill." Pearson replied, "He may be a good source, Jack, but he's a bad man."

On 20th February, 1950, Joe McCarthy made a speech in the Senate supporting the allegations he had made in Salt Lake City. This time he did not describe them as "card-carrying communists" because this had been shown to be untrue. Instead he argued that his list were all "loyalty risks". He also claimed that one of the president's speech-writers, was a communist. Although he did not name him, he was referring to David Demarest Lloyd, the man that Anderson had provided information on.

Lloyd immediately issued a statement where he defended himself against McCarthy's charges. President Harry S. Truman not only kept him on but promoted him to the post of Administrative Assistant. Lloyd was indeed innocent of these claims and McCarthy was forced to withdraw these allegations. As Anderson admitted: "At my instigation, then, Lloyd had been done an injustice that was saved from being grevious only by Truman's steadfastness."

McCarthy now informed Jack Anderson that he had evidence that Professor Owen Lattimore, director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University, was a Soviet spy. Pearson, who knew Lattimore, and while accepting he held left-wing views, he was convinced he was not a spy. In his speeches, McCarthy referred to Lattimore as "Mr X... the top Russian spy... the key man in a Russian espionage ring."

On 26th March, 1950, Pearson named Lattimore as McCarthy's Mr. X. Pearson then went onto defend Lattimore against these charges. McCarthy responded by making a speech in Congress where he admitted: "I fear that in the case of Lattimore I may have perhaps placed too much stress on the question of whether he is a paid espionage agent."

McCarthy then produced Louis Budenz, the former editor of The Daily Worker. Budenz claimed that Lattimore was a "concealed communist". However, as Jack Anderson admitted: "Budenz had never met Lattimore; he spoke not from personal observation of him but from what he remembered of what others had told him five, six, seven and thirteen years before."

Pearson now wrote an article where he showed that Budenz was a serial liar: "Apologists for Budenz minimize this on the ground that Budenz has now reformed. Nevertheless, untruthful statements made regarding his past and refusal to answer questions have a bearing on Budenz's credibility." He went on to point out that "all in all, Budenz refused to answer 23 questions on the ground of self-incrimination".

Owen Lattimore was eventually cleared of the charge that he was a Soviet spy or a secret member of the American Communist Party and like several other victims of McCarthyism, he went to live in Europe and for several years was professor of Chinese studies at Leeds University.

Despite the efforts of Jack Anderson, by the end of June, 1950, Drew Pearson had written more than forty daily columns and a significant percentage of his weekly radio broadcasts, that had been devoted to discrediting the charges made by Joseph McCarthy. He now decided to take on Pearson and he told Anderson: "Jack, I'm going to have to go after your boss. I mean, no holds barred. I figure I've already lost his supporters; by going after him, I can pick up his enemies." McCarthy, when drunk, told Assistant Attorney General Joe Keenan, that he was considering "bumping Pearson off".

On 15th December, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in Congress where he claimed that Pearson was "the voice of international Communism" and "a Moscow-directed character assassin." McCarthy added that Pearson was "a prostitute of journalism" and that Pearson "and the Communist Party murdered James Forrestal in just as cold blood as though they had machine-gunned him."

Over the next two months Joseph McCarthy made seven Senate speeches on Drew Pearson. He called for a "patriotic boycott" of his radio show and as a result, Adam Hats, withdrew as Pearson's radio sponsor. Although he was able to make a series of short-term arrangements, Pearson was never again able to find a permanent sponsor. Twelve newspapers cancelled their contract with Pearson.

Joe McCarthy and his friends also raised money to help Fred Napoleon Howser, the Attorney General of California, to sue Pearson for $350,000. This involved an incident in 1948 when Pearson accused Howser of consorting with mobsters and of taking a bribe from gambling interests. Help was also given to Father Charles Coughlin, who sued Pearson for $225,000. However, in 1951 the courts ruled that Pearson had not libeled either Howser or Coughlin.

Only the St. Louis Star-Times defended Pearson. As its editorial pointed out: "If Joseph McCarthy can silence a critic named Drew Pearson, simply by smearing him with the brush of Communist association, he can silence any other critic." However, Pearson did get the support of J. William Fulbright, Wayne Morse, Clinton Anderson, William Benton and Thomas Hennings in the Senate.

In October, 1953, Joe McCarthy began investigating communist infiltration into the military. Attempts were made by McCarthy to discredit Robert T. Stevens, the Secretary of the Army. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was furious and now realised that it was time to bring an end to McCarthy's activities.

The United States Army now passed information about McCarthy to journalists who were known to be opposed to him. This included the news that McCarthy and Roy Cohn had abused congressional privilege by trying to prevent David Schine from being drafted. When that failed, it was claimed that Cohn tried to pressurize the Army into granting Schine special privileges. Pearson published the story on 15th December, 1953.

Some figures in the media, such as writers George Seldes and I. F. Stone, and cartoonists, Herb Block and Daniel Fitzpatrick, had fought a long campaign against McCarthy. Other figures in the media, who had for a long time been opposed to McCarthyism, but were frightened to speak out, now began to get the confidence to join the counter-attack. Edward Murrow, the experienced broadcaster, used his television programme, See It Now, on 9th March, 1954, to criticize McCarthy's methods. Newspaper columnists such as Walter Lippmann also became more open in their attacks on McCarthy.

The senate investigations into the United States Army were televised and this helped to expose the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process, McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

McCarthy also lost the chairmanship of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. He was now without a power base and the media lost interest in his claims of a communist conspiracy. As one journalist, Willard Edwards, pointed out: "Most reporters just refused to file McCarthy stories. And most papers would not have printed them anyway."

In 1956 Pearson began investigating the relationship between Lyndon B. Johnson and two businessmen, George R. Brown and Herman Brown. Pearson believed that Johnson had arranged for the Texas-based Brown and Root Construction Company to avoid large tax bills. Johnson brought an end to this investigation by offering Pearson a deal. If Pearson dropped his Brown-Root crusade, Johnson would support the presidential ambitions of Estes Kefauver. Pearson accepted and wrote in his diary (16th April, 1956): "This is the first time I've ever made a deal like this, and I feel a little unhappy about it. With the Presidency of the United States at stake, maybe it's justified, maybe not - I don't know."

Jack Anderson also helped Pearson investigate stories of corruption inside the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower. They discovered that Eisenhower had received gifts worth more than $500,000 from "big-business well-wishers." In 1957 Anderson threaten to quit because these stories always appeared under Pearson's name. Pearson responded by promising him more bylines and pledged to leave the column to him when he died.

Pearson and Anderson began investigating the presidential assistant Sherman Adams. The former governor of New Hampshire, was considered to be a key figure in Eisenhower's administration. Anderson discovered that Bernard Goldfine, a wealthy industrialist, had given Adams a large number of presents. This included suits, overcoats, alcohol, furnishings and the payment of hotel and resort bills. Anderson eventually found evidence that Adams had twice persuaded the Federal Trade Commission to "ease up its pursuit of Goldfine for putting false labels on the products of his textile plants."

The story was eventually published in 1958 and Adams was forced to resign from office. However, Jack Anderson was much criticized for the way he carried out his investigation and one of his assistants, Les Whitten, was arrested by the FBI for receiving stolen government documents.

In 1960 Pearson supported Hubert Humphrey in his efforts to become the Democratic Party candidate. However, those campaigning for John F. Kennedy, accused him of being a draft dodger. As a result, when Humphrey dropped out of the race, Pearson switched his support to Lyndon B. Johnson. However, it was Kennedy who eventually got the nomination.

Pearson now supported Kennedy's attempt to become president. One of the ways he helped his campaign was to investigate the relationship between Howard Hughes and Richard Nixon. Pearson and Anderson discovered that in 1956 the Hughes Tool Company provided a $205,000 loan to Nixon Incorporated, a company run by Richard's brother, Francis Donald Nixon. The money was never paid back. Soon after the money was paid the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) reversed a previous decision to grant tax-exempt status to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This information was revealed by Pearson and Jack Anderson during the 1960 presidential campaign. Nixon initially denied the loan but later was forced to admit that this money had been given to his brother. It was claimed that this story helped John F. Kennedy defeat Nixon in the election.

In 1963 Senator John Williams of Delaware began investigating the activities of Bobby Baker. As a result of his work, Baker resigned as the secretary to Lyndon B. Johnson on 9th October, 1963. During his investigations Williams met Don B. Reynolds and persuaded him to appear before a secret session of the Senate Rules Committee.

Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his committee on 22nd November, 1963, that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for him agreeing to this life insurance policy. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds was also told by Walter Jenkins that he had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson.

Don B. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Bobby Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". Reynolds also provided evidence against Matthew H. McCloskey. He suggested that he given $25,000 to Baker in order to get the contract to build the District of Columbia Stadium. His testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

As soon as Johnson became president he contacted B. Everett Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because " it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread."

Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds.

On 17th January, 1964, the Committee on Rules and Administration voted to release to the public Reynolds' secret testimony. Johnson responded by leaking information from Reynolds' FBI file to Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953.

A few weeks later the New York Times reported that Lyndon B. Johnson had used information from secret government documents to smear Don B. Reynolds. It also reported that Johnson's officials had been applying pressure on the editors of newspapers not to print information that had been disclosed by Reynolds in front of the Senate Rules Committee.

In 1966 attempts were made to deport Johnny Roselli as an illegal alien. Roselli moved to Los Angeles where he went into early retirement. It was at this time he told attorney, Edward Morgan: "The last of the sniper teams dispatched by Robert Kennedy in 1963 to assassinate Fidel Castro were captured in Havana. Under torture they broke and confessed to being sponsored by the CIA and the US government. At that point, Castro remarked that, 'If that was the way President Kennedy wanted it, Cuba could engage in the same tactics'. The result was that Castro infiltrated teams of snipers into the US to kill Kennedy".

Morgan took the story to Pearson. The story was then passed on to Earl Warren. He did not want anything to do with it and so the information was then passed to the FBI. When they failed to investigate the story Jack Anderson wrote an article entitled "President Johnson is sitting on a political H-bomb" about Roselli's story. It has been suggested that Roselli started this story at the request of his friends in the Central Intelligence Agency in order to divert attention from the investigation being carried out by Jim Garrison.

In 1968 Jack Anderson and Drew Pearson published The Case Against Congress. The book documented examples of how politicians had "abused their power and priviledge by placing their own interests ahead of those of the American people". This included the activities of Bobby Baker, James Eastland, Lyndon B. Johnson, Dwight Eisenhower, Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, Thomas J. Dodd, John McClellan and Clark Clifford.

On 18th July, 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne, died while in the car of Edward Kennedy. Pearson began investigating the case when he died on 1st September. Chalmers Roberts of the Washington Post wrote: "Drew Pearson was a muckraker with a Quaker conscience. In print he sounded fierce; in life he was gentle, even courtly. For thirty-eight years he did more than any man to keep the national capital honest."

Primary Sources

(1) Jack Anderson, Confessions of a Muckraker (1979)

The motivation behind most of his (Drew Pearson) crusades was his Quaker pacifism and a conviction that peoples must reach out, over governmental barriers, to aid and communicate with one another lest the horrors of the past be repeated.

In the late 1930s he had put aside his Quaker principles because of the overriding peril he saw in totalitarian aggression, and he effectively supported the Roosevelt interventionist policies and the war effort. But at war's end he became plagued with alarming visions - an America permanently militarized, the sweep of Stalinism into Western Europe, a world divided by backward-looking politicians into hostile East-West camps. He had emerged from the war years as the single most influential commentator in the world, and he determined to use that influence...

With his daily "Merry-Go-Round" column and his Sunday-night broadcast over the ABC radio network, the Pearson operation reached an audience of 60 million. The name Drew Pearson evoked the image of the ubiquitous, hyperactive news hawk, with open collar, clipped mustache, the inevitable reporter's hat set back on his head, fast-talking into a mike. So much did his public image fit the mystique of the reporter-sleuth that a comic strip based on his career ("Hap Hazard") was being syndicated in competition with Dick Tracy. No other American had ever had the eyes and ears of so many people for so long a time.

He used this unprecedented access to help what he saw as the humanitarian cause and to hurt those who thwarted it - imperialists, militarists, monopolists, racists, crooks in public and corporate life, all of whom he saw as subverters of the American system and exploiters of the poor. On the attack he was unremitting, and even when not mortally engaged, he thought it salutary that the mighty should be humbled. He often trampled upon the customary immunity granted by the correspondents of that day to the highly placed as regards their private vices, self-indulgences and eccentricities.

(2) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

Upon my return from furlough, my officers were confident that I would be transferred back into the battalion. In fact, an order to this effect arrived soon afterwards from Armored Force Headquarters. I thought victory was finally at hand, when everything was upset again. Newspaper columnist Drew Pearson published an account of my case just as I have described it here. Syndicated coast-to-coast, the column meant well but it contained all kinds of unauthorized, secret military information-the name of my battalion, the fact that it had been alerted for overseas, my letter to the President and his reply, and the officers' affidavits. As a result of this violation of military secrecy, the date for the outfit going overseas was postponed, the order restoring me to my battalion was countermanded and I was out of it for good. It seems that some of my friends, a bit overzealous in my cause, had given Pearson all this information, thinking the publicity would do me good.

(3) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-Go-Round (13th November, 1947)

Republicans who will have to pass upon the qualifications of James Forrestal for the all-important job of Secretary of National Defense have been checking into his background and have stumbled onto some highly interesting facts. Back in the first years of the Roosevelt Administration, Forrestal was exposed by the Senate Banking Committee probe for having got around a $840,000 income-tax payment by setting up a personal holding corporation. This Senate Banking probe also exposed Forrestal's banking firm - Dillon, Read & Co. - as one of the worst highbinders on Wall Street when it came to floating bad loans to Germany and Latin America. As a result of this investigation, Roosevelt set up the Securities and Exchange Commission. Now, however, Republicans point out that the head of a Wall Street house with one of the worst records of all has become head of the combined Army and Navy.

(4) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-Go-Round (4th August, 1948)

One Congressman who has sadly ignored the old adage that those who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones is bouncing Rep. J. Parnell Thomas of New Jersey, Chairman of the UnAmerican Activities Committee.

If some of his own personal operations were scrutinized on the witness stand as carefully as he cross-examines witnesses, they would make headlines of a kind the Congressman doesn't like.

It is not, for instance, considered good "Americanism" to hire a stenographer and have her pay a "kickback." This kind of operation is also likely to get an ordinary American in income tax trouble. However, this hasn't seemed to worry the Chairman of the UnAmerican Activities Committee.

On Jan. 1, 1940, Rep. Thomas placed on his payroll Myra Midkiff as a clerk at $1,200 a year with the arrangement that she would then kick back all her salary to the Congressman. This gave Mr. Thomas a neat annual addition to his own $10,000 salary, and presumably he did not have to worry about paying income taxes in this higher bracket, because he paid Miss Midkiff's taxes for her in the much lower bracket.

The arrangement was quite simple and lasted for four years. Miss Midkiff's salary was merely deposited in the First National Bank of Allendale, N.J., to the Congressman's account. Meanwhile she never came anywhere near his office and did not work for him except addressing envelopes at home for which she got paid $2 per hundred.

This kickback plan worked so well that four years later. Miss Midkiff having got married and left his phantom employ, the Congressman decided to extend it. On Nov. 16, 1944, the House Disbursing Officer was notified to place on Thomas's payroll the name of Arnette Minor at $1,800 a year.

Actually Miss Minor was a day worker who made beds and cleaned the room of Thomas's secretary, Miss Helen Campbell. Miss Minor's salary was remitted to the Congressman. She never got it.

This arrangement lasted only a month and a half, for on Jan. 1, 1945, the name of Grace Wilson appeared on the Congressman's payroll for $2,900.

Miss Wilson turned out to be Mrs. Thomas's aged aunt, and during the year 1945 she drew checks totaling $3,467.45, though she did not come near the office, in fact remained quietly in Allendale, N.J., where she was supported by Mrs. Thomas and her sisters, Mrs. Lawrence Wellington and Mrs. William Quaintance.

In the summer of 1946, however, the Congressman decided to let the county support his wife's aunt, since his son had recently married and he wanted to put his daughter-in-law on the payroll. Thereafter, his daughter-in-law, Lillian, drew Miss Wilson's salary, and the Congressman demanded that his wife's aunt be put on relief.

(5) Drew Pearson, comments made to Jack Anderson in 1948.

Jack, Forrestal is the most dangerous man in America. Sure he's able. Of course he's dedicated. But to what? He's a man who lives only for himself. He has broken his word, turned his back on his friends. He is driven by one ambition; he has always craved to be top man - first of Wall Street and now of the United States. Any principles he has are the kind that will cause another world war - unless he's stopped first."

(6) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-Go-Round (15th December, 1948)

Ever since election day, Secretary of Defense Forrestal has been frantically painting himself a true and loyal Democrat. But there is has been frantically painting himself a true and loyal Democrat. But here is an off-the-record talk indicating the kind of men Forrestal puts in high position...

Practically all Latin America is watching the State Department to see what we do about recognizing the new Army dictatorship in Venezuela... the State Department's trigger-recognition of Latin dictators has brought forth a rash of military revolts, the latest being the Nicaraguan-inspired march against the peaceful government of Costa Rica...

Secretary of Defense Forrestal still favors his plan of sending more arms to Latin America under a new lend-lease agreement, despite the fact that new arms to Latin American generals are like a toy train to a small boy at Christmastime. They can't wait to use them - usually against their own President.

General Somoza, the Nicaraguan who has now inspired the fracas in Costa Rica, was trained by the U.S. Marines, later seized the Presidency of Nicaragua. President Trujillo, worst dictator in all Latin America, was also trained by the U.S. Marines. Unfortunately, under the Forrestal-Marine Corps program, we train men to shoot and give them the weapons to shoot with. But we don't give them any ideas or ideals as to what they should shoot for.

Back in the 1920's, Secretary Forrestal's Wall Street firm loaned 20 million dollars to Bolivia, used to buy arms to wage war against Paraguay. Some time after Forrestal loaned this money to Bolivia, the Remington Arms Co., of which Donald Carpenter is now vice president, stepped in to profit by it. Remington got a contract for 7.65 mm. and 9 mm. cartridges. Carpenter had just joined the firm when this sale was made. So Forrestal and Carpenter, once operators in indirectly fomenting war in Latin America, are now together in running American defense.

(7) Drew Pearson, Washington Post (30th May, 1949)

In the end, it may be found that Mr. Forrestal's friends had more to do with his death than his critics. For those close to him now admit privately that he had been sick for some time, suffered embarrassing lapses too painful to be mentioned here.

Yet during the most of last winter, when Jim Forrestal was under heavy responsibilities and definitely not a well man, the little coterie of newspapermen who now insinuate Jim was killed by his critics, encouraged him to stay on. This got to be almost an obsession, both on their part and on his, until Mr. Truman's final request for his resignation undoubtedly worsened the illness.

The real fact is that Jim Forrestal had a relatively good press. All one need do is examine the newspaper files to see that his press was far better than that of some of his old associates.

Are public officials to be immune from criticism or investigation for fear of impairing their health? If we are to withhold the check of congressional investigation or newspaper criticism from any public official, no

matter how mild, because of health, then the Government of checks and balances created by the Founding Fathers is thrown out of gear.

It was not criticism which caused Jim Forrestal to conclude that his life was no longer worth living. There were other factors in his life that made him unhappy.

(8) Drew Pearson, diary (22nd May, 1949)

Jim Forrestal died at 2 a.m. by jumping out of the Naval Hospital window...

I think that Forrestal really died because he had no spiritual reserves. He had spent all his life thinking only about himself, trying to fulfill his great ambition to be President of the United States. When that ambition became out of his reach, he had nothing to fall back on. He had no church; he had deserted it. He had no wife. They had both deserted each other. She was in Paris at the time of his death - though it was well-known that he had been seriously ill for weeks. But most important of all, he had no spiritual resources...

But James Forrestal's passion was public approval. It was his lifeblood. He craved it almost as a dope addict craves morphine. Toward the end he would break down and cry pitifully, like a child, when criticized too much. He had worked hard - too much in fact - for his country. He was loyal and patriotic. Few men were more devoted to their country, but he seriously hurt the country that he loved by taking his own life. All his policies now are under closer suspicion than before...

Forrestal not only had no spiritual resources, but also he had no calluses. He was unique in this respect. He was acutely sensitive. He had traveled not on the hard political path of the politician, but on the protected, cloistered avenue of the Wall Street bankers. All his life he had been surrounded by public relations men. He did not know what the lash of criticism meant. He did not understand the give-and-take of the political arena. Even in the executive branch of government, he surrounded himself with public relations men, invited newsmen to dinner, lunch, and breakfast, made a fetish of courting their favor. History unfortunately will decree that Forrestal's great reputation was synthetic. It was built on the most unstable foundation of all - the handouts of paid press agents.

If Forrestal had been true to his friends, if he had made one sacrifice for a friend, if he had even gone to bat for Tom Corcoran who put him in the White House, if he had spent more time with his wife instead of courting his mistress, he would not have been so alone this morning when he went to the diet pantry of the Naval Hospital and jumped to his death.

(9) Saturday Evening Post (18th June, 1949)

It is an interesting speculation as to what extent Forrestal's desperation was deepened by a group of ill-assorted columnists and ideological libertarians. During his whole Government service it was implied in a continuous stream of billingsgate that Forrestal was in the Government to serve his former partners in the investment-banking business, that he was a "cartelist" and a truckler to fascism.

It is a little late to go into all that, but it is not too late to make the obvious comment that the responsibility for this abuse of a free press goes beyond the malice of gossip columnists and rests firmly on the heads of publishers who permit their newspapers to take from syndicated columnists libelous and half-baked abuse which they would not print if it were written by their own reporters.

It is not necessary to have agreed with everything James Forrestal believed or did, but it is reasonable to

insist that news and opinion regarding the acts of public men or private citizens for that matter, be held to ordinary standards of accuracy, fairness and decency.

(10) Drew Pearson, diary entry (28th November, 1949)

Parnell Thomas's trial started this morning. Looking at him in the courtroom. I couldn't help but feel sorry for him. I can't relish helping to send a man to jail. Nevertheless, when I figure all the times Thomas has sent other people to jail and all the instances when he has kept men away from combat duty in return for money in his own pocket, to say nothing of salary kickbacks, perhaps I shouldn't be too sorry.

(11) Drew Pearson, Washington Merry-Go-Round (18th September, 1950)

Senator Brewster in 1947 was chairman of the powerful Senate War Investigating Committee. He was also the bosom friend of Pan American Airways. Brewster and Pan American wanted Howard Hughes's TWA to consolidate its overseas lines with Pan Am. This Hughes refused to do. Whereupon Brewster investigated Hughes, and, during the period when he was before Brewster's Senate committee, Hughes's telephone wire and that of his attorneys were tapped, apparently under the off-stage direction of Henry Grunewald, who admits that at various times he checked telephone wires for Pan American Airways.

Grunewald and others deny this. Nevertheless this is the conclusion which Senators are forced to arrive at. No wonder businessmen who come to Washington are worried about talking over telephones. They never know when some competitor, perhaps with the cooperation of a Senate committee, is listening in. Yet this is supposed to be the capital of the USA not Moscow.

(12) Drew Pearson, diary entry (24th April, 1951)

This afternoon McCarthy sounded off with another speech on the Senate floor claiming that the Justice Department had now finished its investigation and had a complete espionage case against me. He also pontificated that I had received State Department documents from the State Department via Dave Karr, whom he described as a top member of the Communist party. McCarthy also claimed that the column today, which dealt with developments in the atomic bomb field, paraphrased a secret report and was a violation of security.

(13) Drew Pearson, diary entry (21st May, 1951)

The facts were that MacArthur had wasted blood most of his career, not only in Korea. I urged the Joint Chiefs of Staff, when they testify, should show up MacArthur's glaring errors and his well-known "extravagance with his men". For instance, General Eichelberger, who commanded the 8th Army during World War II, could testify to MacArthur's shameful laxness on New Guinea and his refusal to visit the front at Buna even once.

(14) Jack Anderson, Confessions of a Muckraker (1979)

Drew Pearson was nearing his fiftieth year and the pinnacle of his influence when I joined his staff. During my first days on the job, the senior staffmen alerted me against stumbling over established taboos: Mr. Pearson did not tolerate certain activities around him, such as smoking; he brooked no insubordination; he did not appreciate questions on how to proceed, expecting his reporters to know how to carry out his missions impossible. He could not abide air conditioning, so one must not leave open the door to his den which would let in drafts from the air conditioners in the staff rooms. No one was allowed to use, or even touch, his personal typewriter, an antique portable Corona given him by his revered father in 1922. He required little sleep and was apt to phone his reporters at any hour of the night, as the spirit moved him; I must learn to come out of a deep sleep instantly and to make a show of alertness, if not joviality, at three o'clock in the morning.

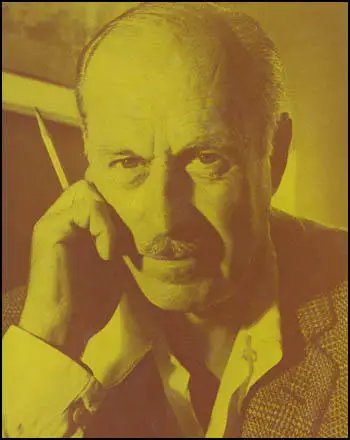

So forewarned, I approached Mr. Pearson with apprehension in the beginning. But the polecat in his lair was disarmingly mild. Sitting behind his paper-strewn desk in a maroon smoking jacket, or in the bathrobe he wore some days until noon, amid pictures and mementoes of his much-loved family, with a black cat named Cinders preening companionably in the out-box on his desk, he appeared not at all menacing. When he arose, he revealed a frame that was tall, trim and well constructed, conveying an impression of considerable physical strength. He had an impressive, high forehead under thinning light-brown hair, and a general look of learnedness that made him seem too dignified and elegant for the rough-and-tumble he in fact relished. The anguished visitor who missed the occasional glint of watchfulness in his blue eyes would likely be lulled by his soft voice, quiet manners and the peaceful gentility of the atmosphere into the comfortable feeling that he was paying a courtesy call on Mr. Chips.

Conversation with him did not flow easily. Despite his prodigious production of the written word and an experience as a public lecturer that spanned several continents and went back almost to his adolescence, he often seemed ill at ease in conversation. He could be a most gracious host, with a disciplined adherence to the ordinary courtesies, but he quickly became bored with small talk. He was a listener more than a discourses He spoke slowly and would join in intermittently when some subject sparked his interest, then would lapse into silences that could become awkward.

(15) Jack Anderson, Peace, War, And Politics (1999)

Drew Pearson took off the month of August 1969 for a vacation and, as had become his habit, left the office in my charge. Just a few days earlier, Senator Ted Kennedy had fallen victim to the family curse: he drove his Oldsmobile off the narrow Dyke Bridge into Poucha Pond on Chappaquiddick Island, plunging his passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, to her death. Drew left behind a column to run under his byline predicting that the tragedy would dog Kennedy for the rest of his life.

I was busy mobilizing the staff to break through the thick net of half-truths thrown up by the Kennedy propaganda machine when I got a call from Luvie Pearson. Drew had suffered a heart attack. Luvie's voice was even and unruffled, calming the anxiety that welled up in me. Drew needed a few weeks to recuperate, Luvie said. She suggested that no one from the office stress him with phone calls or visits.

One night a few weeks later, I answered the phone to hear Drew's weakened, thin voice. Why hadn't I come to visit him? I hurried out to his farm on the Potomac the next day and found him sitting at his typewriter. He had a paragraph in the making about the state of medical care. "I thought I would help you out," he said, with a tone of sheepishness. I assured him we would muddle along without him. Two days later on September I, 1969, he collapsed in his garden and was dead.